Unsolved:Oni

An oni (

During the Heian period (794–1185), oni were often depicted in Japanese literature, such as setsuwa, as terrifying monsters that ate people. A prominent depiction of oni is that they eat people in one mouthful, which is called "onihitokuchi". In Nihon Ryōiki, The Tales of Ise and Konjaku Monogatarishū, for example, a woman is shown being eaten in one mouthful by an oni.[7] There is the theory that the reason why stories of onihitokuchi were common is that wars, disasters, and famines where people lose their lives or go missing were interpreted as oni from another world appearing in the present world who take away humans.[8]

It was not until the legend of Shuten-dōji was created that the oni began to be depicted in paintings,[9] and the 14th century Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist. is the oldest surviving Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist. depicting Shuten-dōji. Shuten-dōji has been regarded as the most famous and strongest oni in Japan. The legend of Shuten-dōji has been described since the 14th century in various arts, traditional performing arts and literature such as emakimono, jōruri, noh, kabuki, bunraku, and ukiyo-e. The tachi (Japanese long sword) "Dōjigiri" with which Minamoto no Yorimitsu decapitated Shuten-dōji' in the legend is now designated as a National Treasure and one of the Tenka-Goken (Five Greatest Swords Under Heaven).[10][11]

They are popular characters in Japanese art, literature, and theater[12] and appear as stock villains in the well-known fairytales of Momotarō (Peach Boy), Issun-bōshi, and Kobutori Jīsan. Although oni have been described as frightening creatures, they have become tamer in modern culture as people tell less frightening stories about them like Oni Mask and Red Oni Who Cried.

Etymology, change of meaning

Oni, written in kanji as 鬼, is read in China as guǐ (pinyin), meaning something invisible, formless, or unworldly, in other words, a 'ghost' or the 'soul of the dead'. On the other hand, the Japanese dictionary Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist. written in Japan in the 10th century explained the origin of the word oni as a corruption of Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist., meaning 'to hide'. The dictionary explained that oni is hidden and does not want to reveal itself. When the character for 鬼 was first introduced to Japan, it was pronounced as Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist. in the on'yomi reading.[9][13][14]

The character 鬼 has changed over time in Japan to become its own entity, and there are significant differences between the Japanese Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist. and the Chinese guǐ (鬼). The Chinese guǐ generally refers to the disembodied spirits of the dead and are not necessarily evil. They usually reside in the underworld, but those with a grudge sometimes appear in the human world to haunt, and Taoist priests and others have used their supernatural powers to exterminate them. Japanese Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist., on the other hand, are evil beings that have substance, live in certain places in the human world, such as mountains, have red or blue bodies with horns and fangs, are armed with Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist., and can be physically killed by cutting with Japanese swords.[15][9][13]

The Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist. and Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist. are the earliest written examples of oni as entities rather than soul of the dead. The Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist., whose compilation began in 713, tells the story of a one-eyed oni who ate a man. Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist., completed in 720, tells of a hat (kasa)-wearing oni watching the funeral of Emperor Saimei from the top of Mount Asakura. The character for 鬼 is believed to have been read as oni when the Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist. was completed,[13] and was also read as kami, mono, and shiko in the Heian period. In Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist., the character for 鬼 is read as mono. It was not until the end of the Heian period that the reading of oni for the character 鬼 became almost universal.[14]

Particularly powerful oni may be described as kishin or kijin (literally "oni god"; the "ki" is an alternate character reading of "oni"), a term used in Japanese Buddhism to refer to Wrathful Deities.

The oni was syncretized with Hindu-Buddhist creatures such as the man-devouring yaksha and the rakshasa, and became the oni who tormented sinners as wardens of Hell (Jigoku), administering sentences passed down by Hell's magistrate, King Yama (Enma Daiō). The hungry ghosts called gaki (餓鬼) have also been sometimes considered a type of oni (the Kanji for "ki" 鬼 is also read "oni"). Accordingly, a wicked soul beyond rehabilitation transforms into an oni after death. Only the very worst people turn into oni while alive, and these are the oni causing troubles among humans as presented in folk tales.

Some scholars have even argued that the oni was entirely a concept of Buddhist mythology.

Oni bring calamities to the land, bringing about war, plague/illness, earthquakes, and eclipses. They have the destructive power of lightning and thunder, which terrifies people through their auditory and visual effects.

Origins

Most Japanese folklore come from the Kojiki (古事記, "Records of Ancient Matters" or "An Account of Ancient Matters") and Nihongi (日本紀, "Japanese Chronicles"). These stories are the history and development of Japan in ancient times. At the beginning of time and space, Takamagahara (高天原, "Plane of High Heaven" or "High Plane of Heaven") came into being, along with the three divine beings Amenominakanushi (天之御中主, The Central Master or "Lord of the August Center of Heaven"), Takamimusubi (高御産巣日神, "High Creator"), and Kamimusubi (神産巣日, The Divine Creator).[16] These three divine beings were known as Kami,[17] and the three together are sometimes referred to as Kotoamatsukami (別天神, literally "distinguishing heavenly kami"). They manifested the entire universe.[17] They were later joined by two more Kami, Umashiashikabihikoji (宇摩志阿斯訶備比古遅神, Energy) and Amenotokotachi (天之常立神, Heaven).

Finally, two lesser Kami were made to establish earth, Izanagi (イザナギ/伊邪那岐/伊弉諾, meaning "He-who-invites" or the "Male-who-invites") and Izanami (イザナミ, meaning "She-who-invites" or the "Female-who-invites").[18] These two were brother and sister. They also are married and had many children, one of them being Kagutsuchi (カグツチ, Fire).[19] Upon birth, Kagutsuchi mortally wounded Izanami, who went to Yomi (黄泉, 黄泉の国, World of Darkness) on her death[20] and was transformed into a Kami of death.[21] Izanami, who gave life in the physical world, continued to do so in the underworld, ultimately creating the very first oni.

Demon gate

According to Chinese Taoism and esoteric Onmyōdō, the ways of yin and yang, the northeasterly direction is termed the kimon (鬼門, "demon gate") and considered an unlucky direction through which evil spirits passed. Based on the assignment of the twelve zodiac animals to the cardinal directions, the kimon was also known as the ushitora (丑寅), or "Ox Tiger" direction. One hypothesis is that the oni's bovine horns and tiger-skin loincloth developed as a visual depiction of this term.[22][23][24]

Temples are often built facing that direction, for example, Enryaku-ji was deliberately built on Mount Hiei which was in the kimon (northeasterly) direction from Kyoto in order to guard the capital, and similarly Kan'ei-ji was built towards that direction from Edo Castle.[25][26]

However, skeptics doubt this could have been the initial design of Enryaku-ji temple, since the temple was founded in 788, six years before Kyoto even existed as a capital, and if the ruling class were so feng shui-minded, the subsequent northeasterly move of the capital from Nagaoka-kyō to Kyoto would have certainly been taboo.[27]

Japanese buildings may sometimes have L-shaped indentations at the northeast to ward against oni. For example, the walls surrounding the Kyoto Imperial Palace have notched corners in that direction.[28]

Traditional culture

The traditional bean-throwing custom to drive out oni is practiced during Setsubun festival in February. It involves people casting roasted soybeans indoors or out of their homes and shouting "Oni wa soto! Fuku wa uchi!" ("鬼は外!福は内!"; "Oni outside! Blessings inside!"), preferably by a strong wrestler.[29][30]

This custom began with the aristocratic and samurai classes in the Muromachi period (1336–1573). According to the Ainōshō (壒嚢鈔),[31] a dictionary compiled in the Muromachi period, the origin of this custom is a legend from the 10th century during the reign of Emperor Uda. According to the legend, a monk on Mount Kurama threw roasted beans into the eyes of oni to make them flinch and flee. Another theory is that the origin of this custom lies in the word Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist., which means bean. The explanation is that in Japanese, Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist. can also be written as Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist., meaning the devil's eye, or Script error: The function "nihongo3" does not exist., meaning to destroy the devil. During the Edo period (1603–1867), the custom spread to Shinto shrines, Buddhist temples and the general public.[32][33][34]

Regionally around Tottori Prefecture during this season, a charm made of holly leaves and dried sardine heads is used as a guard against oni.[35][36]

There is also a well-known game in Japan called oni gokko (鬼ごっこ), which is the same as the game of tag that children in the Western world play. The player who is "it" is instead called the "oni".[37][38]

Oni are featured in Japanese children's stories such as Momotarō (Peach Boy), Issun-bōshi, and Kobutori Jīsan.

Modern times

In more recent times, oni have lost some of their original wickedness and sometimes take on a more protective function. Men in oni costumes often lead Japanese parades to dispel any bad luck, for example.

Japanese buildings sometimes include oni-faced roof tiles called onigawara (鬼瓦), which are thought to ward away bad luck, much like gargoyles in Western tradition.[39]

Many Japanese idioms and proverbs also make reference to oni. For example, the expression "Oya ni ninu ko wa oni no ko" (親に似ぬ子は鬼の子) (Translation: "A child that does not resemble its parents is the child of an oni.") may be used by a parent to chastise a misbehaving child.[40]

They can be used in stories to frighten children into obeying because of their grotesque appearance, savage demeanor, as well as how they can eat people in a single gulp.[41]

Stories

- Momotaro, the Peach Boy,[42] is a well-known story about an elderly couple having the misfortune of never being able to conceive a child, but they find a giant peach that miraculously gives them a boy as their child. As the boy grows, he is made aware of an island of demons where the people are captured and, after their money is taken, kept as slaves and a source of food. Momotaro sets out to travel to the island with some cakes specially made for him, and while on his journey, he meets a dog, a monkey, and a pheasant who partner up with him to defeat the demons on the island, and once the demons have been taken out they recover the treasures and return them to the rightful owners. Momotaro and his companions, after accomplishing their goal, all return to their respective homes.

- Oni Mask[43] is a story where a young girl goes off to work at a ladies' house to make money for her ailing mother. She talks to a mask of her mother's face once she is done with her work to comfort herself. One day, the curious coworkers see the mask and decide to prank her by putting on an oni mask to replace the mother's mask. Seeing the Oni mask, she takes it as a sign that her mother is worse and not getting better, so she leaves after alerting her boss. After trying to run to her mother's side, she is sidetracked by some men gambling by a campfire. The men catch her and ignore her pleas to let her go to her mother and instead make her watch the fire so it does not go out during the game. While she is stoking the fire, she decides to put on the Oni mask to protect her from the flames. At that moment, the men see only a brightly lit Oni through the red glowing flames and, terrified, run away without gathering their money. The girl, after having made sure the fire would not go out, gathers the money, and waits for the men to return for it, but as time grows, she remembers she was going to see her mother and runs to her mother. While she is at home, she sees her mother is healthier than before, and because of the money the gamblers left behind, she has enough to take care of her without going back to work at the ladies' house.

- Red Oni Who Cried[44] is a story of two oni, one red, the other blue. The red one wants to befriend humankind, but they are afraid of it, making the red oni cry. Knowing what the red oni wants, the blue oni devises a plan to make himself the villain by attacking the houses of the humans and allowing the red oni to save the humans from the blue oni, making the red oni a hero to the humans' eyes. After the humans see the red oni protect them from the blue oni, they determine that the red one is a good oni whom they would like to be friends with, which is what the red one wanted. Seeing this exchange, the blue oni decides to leave so as not to cause any misunderstanding with the humans. When the red oni decides to go home to his friend the blue oni, he notices that the blue oni is gone and realizes what the blue oni has done for him and cries from being touched by the blue oni's thoughtfulness and wonderful friendship.

Gallery

-

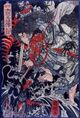

New Forms of Thirty-Six Ghosts: Lord Sadanobu (Fujiwara no Tadahira) Threatens a Demon (Oni) in the Palace at Night. Ukiyo-e printed by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–1892).

-

New Forms of Thirty-Six Ghosts: Omori Hikoshichi carrying a woman across a river; as he does so, he sees that she has horns in her reflection. Ukiyo-e Printed by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi.

-

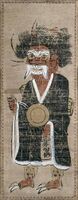

Oni in pilgrim's clothing. Tokugawa period. Hanging scroll, ink and color on paper. 59.2 by 22.1 centimetres (23.3 in × 8.7 in)

-

Depiction of an oni chanting a Buddhist prayer. The oni (ogre or demon) is dressed in the robes of a wandering Buddhist priest. He carries a gong, a striker, and a hogacho (Buddhist subscription list). By Kawanabe Kyōsai, 1864.

In popular culture

Oni remain a very popular motif in Japanese popular culture. Their varied modern depiction sometimes relies on just one or two distinctive features which mark a character as an oni, such as horns or a distinctive skin colour, although the character may otherwise appear human, lacking the oni's traditionally fearsome or grotesque features. The context of oni in popular culture is similarly varied, with instances such as appearances in cartoons, video games, and use as commercial mascots.[citation needed]

- The game series Touhou Project has several characters based on oni such as Suika Ibuki, who is also animated singing the popular song "We Are Japanese Goblin", an example of modern popular culture depicting oni as far less menacing than in the past.[45]

- In the manga YuYu Hakusho and its anime adaptation, oni are the administrative staff of the Spirit World. These oni are shown to be generally benevolent and good-natured, though not always bright. They are depicted in their traditional attire of animal furs and loincloths, resembling stereotypical cavemen.[46]

- The Unicode Emoji character U+1F479 (👹) represents an oni, under the name "Japanese Ogre".

- The video game Overwatch has an oni-themed skin for its character Genji.[47]

- In the video game Ao Oni, the titular oni is depicted as a blue/purplish creature with a large head and human-like features. In the game's 2014 film adaptation, the oni is given a radical makeover to appear more monstrous and scary, while its 2016 anime adaptation remains faithful to its original appearance.

- The video game Genshin Impact has an oni character named Arataki Itto.[48]

- The online multiplayer video game Dead by Daylight features an oni as one of its playable killers.[49]

- The heavy metal band Trivium features an oni mask on their album cover for Silence in the Snow. The mask also appeared in the artwork for their single "Until the World Goes Cold" and in the music video for the song.[50]

- In the animated television series Ninjago: Masters of Spinjitzu, oni are featured as the main antagonists of the "Oni Trilogy" (consisting of the eighth, ninth, and tenth seasons of the show). They are portrayed as a race of malevolent demons who aim to spread darkness and destruction.

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Reider. Japanese Demon Lore : Oni from Ancient Times to the Present. University Press of Colorado. pp. 29–30. https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=3442822.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Oni." Handbook of Japanese Mythology, by Michael Ashkenazi, ABC-CLIO, 2003, pp. 230–233.

- ↑ Reider. Japanese Demon Lore : Oni from Ancient Times to the Present. University Press of Colorado. pp. 34. https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=3442822.

- ↑ Reider. Japanese Demon Lore : Oni from Ancient Times to the Present. University Press of Colorado. pp. 24–25. https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=3442822.

- ↑ Reider. Japanese Demon Lore : Oni from Ancient Times to the Present. University Press of Colorado. pp. 43. https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=3442822.

- ↑ Reider. Japanese Demon Lore: Oni from Ancient Times to the Present. University Press of Colorado. pp. 52–54. https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=3442822.

- ↑ Ensuke Konno (1981). 日本怪談集 妖怪篇 (Nihon Kaidanshū Yōkai hen). Shakai Shisōsha. pp. 190–101. ISBN 978-4-390-11055-6.

- ↑ Takashi Okabe (1992). 日本「神話・伝説」総覧 (Nihon Shinwa Densetsu Sōran). Shinjinbutsu ōraisha. p. 245. ncid: BN08606455.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Naoto Yoshikai (10 January 2023). "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). Doshisha Women's College of Liberal Arts. https://www.dwc.doshisha.ac.jp/research/faculty_column/18257. - ↑ 酒呑童子を退治した天下五剣「童子切安綱」 Naoya Japanese Sword Museum Nagoya Touken World.

- ↑ Shuten-dōji. Kotobank.

- ↑ Lim, Shirley; Ling, Amy (1992). Reading the literatures of Asian America. Temole University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-87722-935-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=X0ntg_EzA0kC&pg=PA242.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Toru Yagi (12 May 2023). "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). Rekishijin. https://www.rekishijin.com/27666. - ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). Japan Knowledge. https://japanknowledge.com/introduction/keyword.html?i=194. - ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). 公益社団法人 日本中国友好協会(日中友好協会). Japan-China Friendship Association. 1 March 2021. https://www.j-cfa.com/report/columu/%E5%BD%A2%E3%81%AE%E3%81%82%E3%82%8B%E3%80%8C%E9%AC%BC%E3%80%8D%E3%81%A8%E5%BD%A2%E3%81%AE%E3%81%AA%E3%81%84%E9%AC%BC/. - ↑ Lewis, Scott. Japanese Mythology. pp. Loc 115 Kindle.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Lewis, Scott. Japanese Mythology. pp. Loc 130 Kindle.

- ↑ Lewis, Scott. Japanese Mythology. pp. Loc 153-176 Kindle.

- ↑ Lewis, Scott. Japanese Mythology. pp. Loc 176-298 Kindle.

- ↑ Lewis, Scott. Japanese Mythology. pp. Loc 298-351.

- ↑ Lewis, Scott. Japanese Mythology. pp. Loc 454 Kindle.

- ↑ Hastings, James (2003). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. Part 8. Kessinger Publishing. p. 611. ISBN 978-0-7661-3678-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=EEQlVC_clo8C&pg=PA611.

- ↑ Reider (2010), p. 7.

- ↑ Foster (2015), p. 119.

- ↑ Havens, Norman; Inoue, Nobutaka (2006). "Konjin". An Encyclopedia of Shinto (Shinto Jiten): Kami. Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics Kokugakuin University. p. 98. ISBN 9784905853084. https://books.google.com/books?id=a_YQAQAAIAAJ&q=Enryakuji+northeast.

- ↑ Frédéric, Louis (2002). "Kan'ei-ji". Japan Encyclopedia. President and Fellows of Harvard College. p. 468. ISBN 978-0-674-00770-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=p2QnPijAEmEC&q=Kan'ei-ji&pg=PA480.

- ↑ Huang Yung-jing 黄永融 (1993), master's thesis, "Fūsui shisō ni okeru gensokusei kara mita Heiankyō wo chūshin to suru Nihon kodai kyūto keikaku no bunseki 風水思想における原則性から見た平安京を中心とする日本古代宮都計画の分析", Kyoto Prefectural University, The Graduate School of Human Life Science. Cited by Yamada, Yasuhiko (1994). Hōi to Fūdo. Kokin Shoin. p. 201. ISBN 9784772213929. https://books.google.com/books?id=STshAQAAMAAJ&q=%22長岡京%22.

- ↑ Parry, Richard Lloyd (1999). Tokyo, Kyoto & ancient Nara. Cadogan Guides. p. 246. ISBN 9781860119170. https://books.google.com/books?id=afQwAQAAIAAJ&q=notch+corner+northeast.: "the walls of the Imperial Palace have a notch in their top-right hand corner to confuse the evil spirits".

- ↑ Foster (2015), p. 125.

- ↑ Sosnoski, Daniel (1966). Introduction to Japanese culture. Charles E. Tuttle Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8048-2056-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=T2blg2Kw_zcC&pg=PP17.

- ↑ Gyōyo (行誉) (1445). Ainōshō (壒嚢鈔). National Institute of Japanese Literature. http://base1.nijl.ac.jp/iview/Frame.jsp?DB_ID=G0003917KTM&C_CODE=MA3-0097&IMG_SIZE=1000%2C800&PROC_TYPE=ON&SHOMEI=%E5%A3%92%E5%9B%8A%E9%88%94&REQUEST_MARK=%E3%83%9E%EF%BC%93%EF%BC%8D%EF%BC%99%EF%BC%97%EF%BC%8D%EF%BC%91%EF%BD%9E%EF%BC%91%EF%BC%95&OWNER=%E5%9B%BD%E6%96%87%E7%A0%94&IMG_NO=70.

- ↑ (in ja). Kikou. 1 February 2019. https://www.kikou.click/blog/entry-143834/.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). Mie Prefecture. https://www.bunka.pref.mie.lg.jp/rekishi/kenshi/asp/hakken/detail.asp?record=303. - ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). nippon.com. 31 January 2019. https://www.nippon.com/ja/guide-to-japan/gu900080/. - ↑ Hearn, Lafcadio (1910). Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan: First and second series. Tauchnitz. p. 296. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZwhLAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA296.

- ↑ Ema, Tsutomu. Ema Tsutomu zenshū. 8. p. 412. https://books.google.com/books?id=WWwNAQAAMAAJ&q=%E6%9F%8A%E9%B0%AF+%E5%9C%B0%E6%96%B9.

- ↑ Chong, Ilyoung (2002). Information Networking: Wired communications and management. Springer-Verlag. p. 41. ISBN 978-3-540-44256-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=eOlQJauoRAEC&pg=PA41.

- ↑ Reider (2010), pp. 155–156.

- ↑ Toyozaki, Yōko (2007). Nihon no ishokujū marugoto jiten. IBC Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-4-89684-640-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=SsmN4jxwnfUC&pg=PA21.

- ↑ Buchanan, Daniel Crump (1965). Japanese Proverbs and Sayings. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-8061-1082-0. https://archive.org/details/japaneseproverbs00buch.

- ↑ Roberts, Jeremy. Japanese Mythology A to Z. Chelsea House Publishers, 2010.

- ↑ Chiba, Kotaro. Tales of Japan: Traditional Stories of Monsters and Magic. Chronicle Books, 2019.

- ↑ Fujita, Hiroko, et al. Folktales from the Japanese Countryside. Libraries Unlimited, 2008.

- ↑ "Japanese Demon Lore: Oni, from Ancient Times to the Present: Reider, Noriko T: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming." Internet Archive, Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1 Jan. 1970, archive.org/details/JapaneseDemonLore/page/n3/mode/2up.

- ↑ "We Are Japanese Goblin". 24 June 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tc8iu0XFUQc.

- ↑ "Anime News, Top Stories & In-Depth Anime Insights". https://www.crunchyroll.com/news/deep-dives/2024/6/24/myth-and-religion-in-yu-yu-hakusho-part-1.

- ↑ Frank, Allegra (2016-11-04). "Playing Heroes of the Storm gets Overwatch fans a special skin" (in en). https://www.polygon.com/2016/11/4/13524624/overwatch-oni-genji-skin-heroes-of-the-storm.

- ↑ Kengly, Rain (23 January 2022). "Genshin Impact: The Legend of the Crimson Oni & the Blue Oni". https://screenrant.com/genshin-impact-crimson-oni-blue-arataki-itto-quest/.

- ↑ "Dead by Daylight Reveals New Killer". 19 November 2019. https://comicbook.com/gaming/news/dead-by-daylight-new-killer-survivor-chapter/.

- ↑ "Trivium - Until The World Goes Cold [OFFICIAL VIDEO"]. 27 August 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pm-xlwkQ_qc.

Bibliography

- Foster, Michael Dylan (2015). The Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore. Shinonome, Kijin (illustr.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520959125. https://books.google.com/books?id=FdzjBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA125.

- Reider, Noriko T. (2003), "Transformation of the Oni: From the Frightening and Diabolical to the Cute and Sexy", Asian Folklore Studies 62 (1): 133–157, http://warp.da.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/8753502/nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/nfile/591

- Reider, Noriko T. (2010). Japanese Demon Lore: Oni from Ancient Times to the Present. Utah State University Press. ISBN 978-0874217933. https://archive.org/details/JapaneseDemonLore.

- Reider, Noriko T. (2016). Seven Demon Stories from Medieval Japan. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-1607324904. https://books.google.com/books?id=y549DQAAQBAJ.

External links

|