Vitali covering lemma

In mathematics, the Vitali covering lemma is a combinatorial and geometric result commonly used in measure theory of Euclidean spaces. This lemma is an intermediate step, of independent interest, in the proof of the Vitali covering theorem. The covering theorem is credited to the Italian mathematician Giuseppe Vitali.[1] The theorem states that it is possible to cover, up to a Lebesgue-negligible set, a given subset E of Rd by a disjoint family extracted from a Vitali covering of E.

Vitali covering lemma

There are two basic version of the lemma, a finite version and an infinite version. Both lemmas can be proved in the general setting of a metric space, typically these results are applied to the special case of the Euclidean space

. In both theorems we will use the following notation: if

is a ball and

, we will write

for the ball

.

Finite version

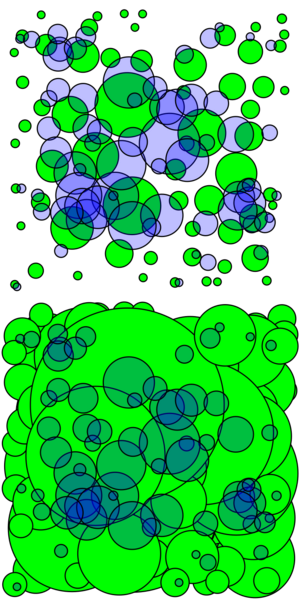

Theorem (Finite Covering Lemma). Let be any finite collection of balls contained in an arbitrary metric space. Then there exists a subcollection of these balls which are disjoint and satisfy Proof: Without loss of generality, we assume that the collection of balls is not empty; that is, n > 0. Let be the ball of largest radius. Inductively, assume that have been chosen. If there is some ball in that is disjoint from , let be such ball with maximal radius (breaking ties arbitrarily), otherwise, we set m := k and terminate the inductive definition.

Now set . It remains to show that for every . This is clear if . Otherwise, there necessarily is some such that intersects . We choose the minimal possible and note that the radius of is at least as large as that of . The triangle inequality then implies that , as needed. This completes the proof of the finite version.

Infinite version

Theorem (Infinite Covering Lemma). Let be an arbitrary collection of balls in a separable metric space such that where denotes the radius of the ball B. Then there exists a countable sub-collection such that the balls of are pairwise disjoint, and satisfyAnd moreover, each intersects some with .

Proof: Consider the partition of F into subcollections Fn, n ≥ 0, defined by

That is, consists of the balls B whose radius is in (2−n−1R, 2−nR]. A sequence Gn, with Gn ⊂ Fn, is defined inductively as follows. First, set H0 = F0 and let G0 be a maximal disjoint subcollection of H0 (such a subcollection exists by Zorn's lemma). Assuming that G0,...,Gn have been selected, let

and let Gn+1 be a maximal disjoint subcollection of Hn+1. The subcollection

of F satisfies the requirements of the theorem: G is a disjoint collection, and is thus countable since the given metric space is separable. Moreover, every ball B ∈ F intersects a ball C ∈ G such that B ⊂ 5 C.

Indeed, if we are given some , there must be some n be such that B belongs to Fn. Either B does not belong to Hn, which implies n > 0 and means that B intersects a ball from the union of G0, ..., Gn−1, or B ∈ Hn and by maximality of Gn, B intersects a ball in Gn. In any case, B intersects a ball C that belongs to the union of G0, ..., Gn. Such a ball C must have a radius larger than 2−n−1R. Since the radius of B is less than or equal to 2−nR, we can conclude by the triangle inequality that B ⊂ 5 C, as claimed. From this immediately follows, completing the proof.[2]

Remarks

- In the infinite version, the initial collection of balls can be countable or uncountable. In a separable metric space, any pairwise disjoint collection of balls must be countable. In a non-separable space, the same argument shows a pairwise disjoint subfamily exists, but that family need not be countable.

- The result may fail if the radii are not bounded: consider the family of all balls centered at 0 in Rd; any disjoint subfamily consists of only one ball B, and 5 B does not contain all the balls in this family.

- The constant 5 is not optimal. If the scale c−n, c > 1, is used instead of 2−n for defining Fn, the final value is 1 + 2c instead of 5. Any constant larger than 3 gives a correct statement of the lemma, but not 3.

- Using a finer analysis, when the original collection F is a Vitali covering of a subset E of Rd, one shows that the subcollection G, defined in the above proof, covers E up to a Lebesgue-negligible set.[3]

Applications and method of use

An application of the Vitali lemma is in proving the Hardy–Littlewood maximal inequality. As in this proof, the Vitali lemma is frequently used when we are, for instance, considering the d-dimensional Lebesgue measure, , of a set E ⊂ Rd, which we know is contained in the union of a certain collection of balls , each of which has a measure we can more easily compute, or has a special property one would like to exploit. Hence, if we compute the measure of this union, we will have an upper bound on the measure of E. However, it is difficult to compute the measure of the union of all these balls if they overlap. By the Vitali lemma, we may choose a subcollection which is disjoint and such that . Therefore,

Now, since increasing the radius of a d-dimensional ball by a factor of five increases its volume by a factor of 5d, we know that

and thus

Vitali covering theorem

In the covering theorem, the aim is to cover, up to a "negligible set", a given set E ⊆ Rd by a disjoint subcollection extracted from a Vitali covering for E : a Vitali class or Vitali covering for E is a collection of sets such that, for every x ∈ E and δ > 0, there is a set U in the collection such that x ∈ U and the diameter of U is non-zero and less than δ.

In the classical setting of Vitali,[1] the negligible set is a Lebesgue negligible set, but measures other than the Lebesgue measure, and spaces other than Rd have also been considered, as is shown in the relevant section below.

The following observation is useful: if is a Vitali covering for E and if E is contained in an open set Ω ⊆ Rd, then the subcollection of sets U in that are contained in Ω is also a Vitali covering for E.

Vitali's covering theorem for the Lebesgue measure

The next covering theorem for the Lebesgue measure λd is due to (Lebesgue 1910). A collection of measurable subsets of Rd is a regular family (in the sense of Lebesgue) if there exists a constant C such that

for every set V in the collection .

The family of cubes is an example of regular family , as is the family of rectangles in R2 such that the ratio of sides stays between m−1 and m, for some fixed m ≥ 1. If an arbitrary norm is given on Rd, the family of balls for the metric associated to the norm is another example. To the contrary, the family of all rectangles in R2 is not regular.

Theorem — Let E ⊆ Rd be a measurable set with finite Lebesgue measure, and let be a regular family of closed subsets of Rd that is a Vitali covering for E. Then there exists a finite or countably infinite disjoint subcollection such that

The original result of (Vitali 1908) is a special case of this theorem, in which d = 1 and is a collection of intervals that is a Vitali covering for a measurable subset E of the real line having finite measure.

The theorem above remains true without assuming that E has finite measure. This is obtained by applying the covering result in the finite measure case, for every integer n ≥ 0, to the portion of E contained in the open annulus Ωn of points x such that n < |x| < n+1.[4]

A somewhat related covering theorem is the Besicovitch covering theorem. To each point a of a subset A ⊆ Rd, a Euclidean ball B(a, ra) with center a and positive radius ra is assigned. Then, as in the Vitali theorem, a subcollection of these balls is selected in order to cover A in a specific way. The main differences with the Vitali covering theorem are that on one hand, the disjointness requirement of Vitali is relaxed to the fact that the number Nx of the selected balls containing an arbitrary point x ∈ Rd is bounded by a constant Bd depending only upon the dimension d; on the other hand, the selected balls do cover the set A of all the given centers.[5]

Vitali's covering theorem for the Hausdorff measure

One may have a similar objective when considering Hausdorff measure instead of Lebesgue measure. The following theorem applies in that case.[6]

Theorem — Let Hs denote s-dimensional Hausdorff measure, let E ⊆ Rd be an Hs-measurable set and a Vitali class of closed sets for E. Then there exists a (finite or countably infinite) disjoint subcollection such that either or

Furthermore, if E has finite s-dimensional Hausdorff measure, then for any ε > 0, we may choose this subcollection {Uj} such that

This theorem implies the result of Lebesgue given above. Indeed, when s = d, the Hausdorff measure Hs on Rd coincides with a multiple of the d-dimensional Lebesgue measure. If a disjoint collection is regular and contained in a measurable region B with finite Lebesgue measure, then

which excludes the second possibility in the first assertion of the previous theorem. It follows that E is covered, up to a Lebesgue-negligible set, by the selected disjoint subcollection.

From the covering lemma to the covering theorem

The covering lemma can be used as intermediate step in the proof of the following basic form of the Vitali covering theorem.

Theorem — For every subset E of Rd and every Vitali cover of E by a collection F of closed balls, there exists a disjoint subcollection G which covers E up to a Lebesgue-negligible set.

Proof: Without loss of generality, one can assume that all balls in F are nondegenerate and have radius less than or equal to 1. By the infinite form of the covering lemma, there exists a countable disjoint subcollection of F such that every ball B ∈ F intersects a ball C ∈ G for which B ⊂ 5 C. Let r > 0 be given, and let Z denote the set of points z ∈ E that are not contained in any ball from G and belong to the open ball B(r) of radius r, centered at 0. It is enough to show that Z is Lebesgue-negligible, for every given r.

Let denote the subcollection of those balls in G that meet B(r). Note that may be finite or countably infinite. Let z ∈ Z be fixed. For each N, z does not belong to the closed set by the definition of Z. But by the Vitali cover property, one can find a ball B ∈ F containing z, contained in B(r), and disjoint from K. By the property of G, the ball B intersects some ball and is contained in . But because K and B are disjoint, we must have i > N. So for some i > N, and therefore

This gives for every N the inequality

But since the balls of are contained in B(r+2), and these balls are disjoint we see

Therefore, the term on the right side of the above inequality converges to 0 as N goes to infinity, which shows that Z is negligible as needed.[7]

Infinite-dimensional spaces

The Vitali covering theorem is not valid in infinite-dimensional settings. The first result in this direction was given by David Preiss in 1979:[8] there exists a Gaussian measure γ on an (infinite-dimensional) separable Hilbert space H so that the Vitali covering theorem fails for (H, Borel(H), γ). This result was strengthened in 2003 by Jaroslav Tišer: the Vitali covering theorem in fact fails for every infinite-dimensional Gaussian measure on any (infinite-dimensional) separable Hilbert space.[9]

See also

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 (Vitali 1908).

- ↑ The proof given is based on (Evans Gariepy)

- ↑ See the "From the covering lemma to the covering theorem" section of this entry.

- ↑ See (Evans Gariepy).

- ↑ (Vitali 1908) allowed a negligible error.

- ↑ (Falconer 1986).

- ↑ The proof given is based on (Natanson 1955), with some notation taken from (Evans Gariepy).

- ↑ (Preiss 1979).

- ↑ (Tišer 2003).

References

- Evans, Lawrence C.; Gariepy, Ronald F. (1992), Measure Theory and Fine Properties of Functions, Studies in Advanced Mathematics, Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, pp. viii+268, ISBN 0-8493-7157-0

- Falconer, Kenneth J. (1986), The geometry of fractal sets, Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics, 85, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. xiv+162, ISBN 0-521-25694-1

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Vitali theorem", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/v096780

- Lebesgue, Henri (1910), "Sur l'intégration des fonctions discontinues", Annales Scientifiques de l'École Normale Supérieure 27: 361–450, doi:10.24033/asens.624, http://www.numdam.org/item?id=ASENS_1910_3_27__361_0

- Natanson, I. P (1955), Theory of functions of a real variable, New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., pp. 277

- Preiss, David (1979), "Gaussian measures and covering theorems", Commentatione Mathematicae Universitatis Carolinae 20 (1): 95–99, ISSN 0010-2628

- Stein, Elias M.; Shakarchi, Rami (2005), Real analysis. Measure theory, integration, and Hilbert spaces, Princeton Lectures in Analysis, III, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. xx+402, ISBN 0-691-11386-6

- Tišer, Jaroslav (2003), "Vitali covering theorem in Hilbert space", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 355 (8): 3277–3289 (electronic), doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-03-03296-3

- Vitali, Giuseppe (1908) [17 December 1907], "Sui gruppi di punti e sulle funzioni di variabili reali" (in Italian), Atti dell'Accademia delle Scienze di Torino 43: 75–92, https://archive.org/stream/attidellarealeac43real#page/228/mode/2up (Title translation) "On groups of points and functions of real variables" is the paper containing the first proof of Vitali covering theorem.

|