Unit hyperbola

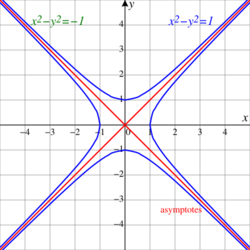

In geometry, the unit hyperbola is the set of points (x,y) in the Cartesian plane that satisfy the implicit equation [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 - y^2 = 1 . }[/math] In the study of indefinite orthogonal groups, the unit hyperbola forms the basis for an alternative radial length

- [math]\displaystyle{ r = \sqrt {x^2 - y^2} . }[/math]

Whereas the unit circle surrounds its center, the unit hyperbola requires the conjugate hyperbola [math]\displaystyle{ y^2 - x^2 = 1 }[/math] to complement it in the plane. This pair of hyperbolas share the asymptotes y = x and y = −x. When the conjugate of the unit hyperbola is in use, the alternative radial length is [math]\displaystyle{ r = \sqrt{y^2 - x^2} . }[/math]

The unit hyperbola is a special case of the rectangular hyperbola, with a particular orientation, location, and scale. As such, its eccentricity equals [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{2}. }[/math][1]

The unit hyperbola finds applications where the circle must be replaced with the hyperbola for purposes of analytic geometry. A prominent instance is the depiction of spacetime as a pseudo-Euclidean space. There the asymptotes of the unit hyperbola form a light cone. Further, the attention to areas of hyperbolic sectors by Gregoire de Saint-Vincent led to the logarithm function and the modern parametrization of the hyperbola by sector areas. When the notions of conjugate hyperbolas and hyperbolic angles are understood, then the classical complex numbers, which are built around the unit circle, can be replaced with numbers built around the unit hyperbola.

Asymptotes

Generally asymptotic lines to a curve are said to converge toward the curve. In algebraic geometry and the theory of algebraic curves there is a different approach to asymptotes. The curve is first interpreted in the projective plane using homogeneous coordinates. Then the asymptotes are lines that are tangent to the projective curve at a point at infinity, thus circumventing any need for a distance concept and convergence. In a common framework (x, y, z) are homogeneous coordinates with the line at infinity determined by the equation z = 0. For instance, C. G. Gibson wrote:[2]

- For the standard rectangular hyperbola [math]\displaystyle{ f = x^2 - y^2 -1 }[/math] in ℝ2, the corresponding projective curve is [math]\displaystyle{ F = x^2 - y^2 - z^2, }[/math] which meets z = 0 at the points P = (1 : 1 : 0) and Q = (1 : −1 : 0). Both P and Q are simple on F, with tangents x + y = 0, x − y = 0; thus we recover the familiar 'asymptotes' of elementary geometry.

Minkowski diagram

The Minkowski diagram is drawn in a spacetime plane where the spatial aspect has been restricted to a single dimension. The units of distance and time on such a plane are

- units of 30 centimetres length and nanoseconds, or

- astronomical units and intervals of 8 minutes and 20 seconds, or

- light years and years.

Each of these scales of coordinates results in photon connections of events along diagonal lines of slope plus or minus one. Five elements constitute the diagram Hermann Minkowski used to describe the relativity transformations: the unit hyperbola, its conjugate hyperbola, the axes of the hyperbola, a diameter of the unit hyperbola, and the conjugate diameter. The plane with the axes refers to a resting frame of reference. The diameter of the unit hyperbola represents a frame of reference in motion with rapidity a where tanh a = y/x and (x,y) is the endpoint of the diameter on the unit hyperbola. The conjugate diameter represents the spatial hyperplane of simultaneity corresponding to rapidity a. In this context the unit hyperbola is a calibration hyperbola[3][4] Commonly in relativity study the hyperbola with vertical axis is taken as primary:

- The arrow of time goes from the bottom to top of the figure — a convention adopted by Richard Feynman in his famous diagrams. Space is represented by planes perpendicular to the time axis. The here and now is a singularity in the middle.[5]

The vertical time axis convention stems from Minkowski in 1908, and is also illustrated on page 48 of Eddington's The Nature of the Physical World (1928).

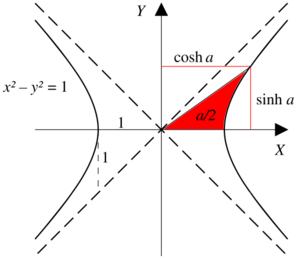

Parametrization

A direct way to parameterizing the unit hyperbola starts with the hyperbola xy = 1 parameterized with the exponential function: [math]\displaystyle{ ( e^t, \ e^{-t}). }[/math]

This hyperbola is transformed into the unit hyperbola by a linear mapping having the matrix [math]\displaystyle{ A = \tfrac {1}{2}\begin{pmatrix}1 & 1 \\ 1 & -1 \end{pmatrix}\ : }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ (e^t, \ e^{-t}) \ A = (\frac{e^t + e^{-t}}{2},\ \frac{e^t - e^{-t}}{2}) = (\cosh t,\ \sinh t). }[/math]

This parameter t is the hyperbolic angle, which is the argument of the hyperbolic functions.

One finds an early expression of the parametrized unit hyperbola in Elements of Dynamic (1878) by W. K. Clifford. He describes quasi-harmonic motion in a hyperbola as follows:

- The motion [math]\displaystyle{ \rho = \alpha \cosh(nt + \epsilon) + \beta \sinh(nt + \epsilon) }[/math] has some curious analogies to elliptic harmonic motion. ... The acceleration [math]\displaystyle{ \ddot{\rho} = n^2 \rho \ ; }[/math] thus it is always proportional to the distance from the centre, as in elliptic harmonic motion, but directed away from the centre.[6]

As a particular conic, the hyperbola can be parametrized by the process of addition of points on a conic. The following description was given by Russian analysts:

- Fix a point E on the conic. Consider the points at which the straight line drawn through E parallel to AB intersects the conic a second time to be the sum of the points A and B.

- For the hyperbola [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 - y^2 = 1 }[/math] with the fixed point E = (1,0) the sum of the points [math]\displaystyle{ (x_1,\ y_1) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ (x_2,\ y_2) }[/math] is the point [math]\displaystyle{ (x_1 x_2 + y_1 y_2,\ y_ 1 x_2 + y_2 x_1 ) }[/math] under the parametrization [math]\displaystyle{ x = \cosh \ t }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y = \sinh \ t }[/math] this addition corresponds to the addition of the parameter t.[7]

Complex plane algebra

Whereas the unit circle is associated with complex numbers, the unit hyperbola is key to the split-complex number plane consisting of z = x + yj, where j 2 = +1. Then jz = y + xj, so the action of j on the plane is to swap the coordinates. In particular, this action swaps the unit hyperbola with its conjugate and swaps pairs of conjugate diameters of the hyperbolas.

In terms of the hyperbolic angle parameter a, the unit hyperbola consists of points

- [math]\displaystyle{ \pm(\cosh a + j \sinh a) }[/math], where j = (0,1).

The right branch of the unit hyperbola corresponds to the positive coefficient. In fact, this branch is the image of the exponential map acting on the j-axis. Thus this branch is the curve [math]\displaystyle{ f(a) = \exp(aj). }[/math] The slope of the curve at a is given by the derivative

- [math]\displaystyle{ f^\prime(a) = \sinh a + j \cosh a = j f(a). }[/math] For any a, [math]\displaystyle{ f^\prime(a }[/math]) is hyperbolic-orthogonal to [math]\displaystyle{ f(a) }[/math]. This relation is analogous to the perpendicularity of exp(a i) and i exp(a i) when i2 = − 1.

Since [math]\displaystyle{ \exp(aj) \exp(bj) = \exp((a+b)j) }[/math], the branch is a group under multiplication.

Unlike the circle group, this unit hyperbola group is not compact. Similar to the ordinary complex plane, a point not on the diagonals has a polar decomposition using the parametrization of the unit hyperbola and the alternative radial length.

References

- ↑ Eric Weisstein Rectangular hyperbola from Wolfram Mathworld

- ↑ C.G. Gibson (1998) Elementary Geometry of Algebraic Curves, p 159, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-64140-3

- ↑ Anthony French (1968) Special Relativity, page 83, W. W. Norton & Company

- ↑ W.G.V. Rosser (1964) Introduction to the Theory of Relativity, figure 6.4, page 256, London: Butterworths

- ↑ A.P. French (1989) "Learning from the past; Looking to the future", acceptance speech for 1989 Oersted Medal, American Journal of Physics 57(7):587–92

- ↑ William Kingdon Clifford (1878) Elements of Dynamic, pages 89 & 90, London: MacMillan & Co; on-line presentation by Cornell University Historical Mathematical Monographs

- ↑ Viktor Prasolov & Yuri Solovyev (1997) Elliptic Functions and Elliptic Integrals, page one, Translations of Mathematical Monographs volume 170, American Mathematical Society

- F. Reese Harvey (1990) Spinors and calibrations, Figure 4.33, page 70, Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-329650-1 .

|