Translation (geometry)

In Euclidean geometry, a translation is a geometric transformation that moves every point of a figure, shape or space by the same distance in a given direction. A translation can also be interpreted as the addition of a constant vector to every point, or as shifting the origin of the coordinate system. In a Euclidean space, any translation is an isometry.

As a function

If is a fixed vector, known as the translation vector, and is the initial position of some object, then the translation function will work as .

If is a translation, then the image of a subset under the function is the translate of by . The translate of by is often written .

Horizontal and vertical translations

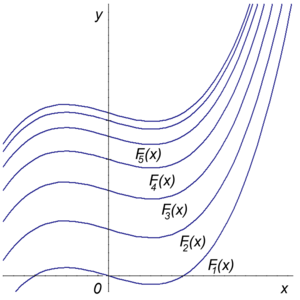

In geometry, a vertical translation (also known as vertical shift) is a translation of a geometric object in a direction parallel to the vertical axis of the Cartesian coordinate system.[1][2][3]

Often, vertical translations are considered for the graph of a function. If f is any function of x, then the graph of the function f(x) + c (whose values are given by adding a constant c to the values of f) may be obtained by a vertical translation of the graph of f(x) by distance c. For this reason the function f(x) + c is sometimes called a vertical translate of f(x).[4] For instance, the antiderivatives of a function all differ from each other by a constant of integration and are therefore vertical translates of each other.[5]

In function graphing, a horizontal translation is a transformation which results in a graph that is equivalent to shifting the base graph left or right in the direction of the x-axis. A graph is translated k units horizontally by moving each point on the graph k units horizontally.

For the base function f(x) and a constant k, the function given by g(x) = f(x − k), can be sketched f(x) shifted k units horizontally.

If function transformation was talked about in terms of geometric transformations it may be clearer why functions translate horizontally the way they do. When addressing translations on the Cartesian plane it is natural to introduce translations in this type of notation:

or

where and are horizontal and vertical changes respectively.

Example

Taking the parabola y = x2 , a horizontal translation 5 units to the right would be represented by T(x, y) = (x + 5, y). Now we must connect this transformation notation to an algebraic notation. Consider the point (a, b) on the original parabola that moves to point (c, d) on the translated parabola. According to our translation, c = a + 5 and d = b. The point on the original parabola was b = a2. Our new point can be described by relating d and c in the same equation. b = d and a = c − 5. So d = b = a2 = (c − 5)2. Since this is true for all the points on our new parabola, the new equation is y = (x − 5)2.

Application in classical physics

In classical physics, translational motion is movement that changes the position of an object, as opposed to rotation. For example, according to Whittaker:[6]

If a body is moved from one position to another, and if the lines joining the initial and final points of each of the points of the body are a set of parallel straight lines of length ℓ, so that the orientation of the body in space is unaltered, the displacement is called a translation parallel to the direction of the lines, through a distance ℓ.

– E. T. Whittaker, A Treatise on the Analytical Dynamics of Particles and Rigid Bodies, p. 1

A translation is the operation changing the positions of all points of an object according to the formula

where is the same vector for each point of the object. The translation vector common to all points of the object describes a particular type of displacement of the object, usually called a linear displacement to distinguish it from displacements involving rotation, called angular displacements.

When considering spacetime, a change of time coordinate is considered to be a translation.

As an operator

The translation operator turns a function of the original position, , into a function of the final position, . In other words, is defined such that This operator is more abstract than a function, since defines a relationship between two functions, rather than the underlying vectors themselves. The translation operator can act on many kinds of functions, such as when the translation operator acts on a wavefunction, which is studied in the field of quantum mechanics.

As a group

The set of all translations forms the translation group , which is isomorphic to the space itself, and a normal subgroup of Euclidean group . The quotient group of by is isomorphic to the orthogonal group :

Because translation is commutative, the translation group is abelian. There are an infinite number of possible translations, so the translation group is an infinite group.

In the theory of relativity, due to the treatment of space and time as a single spacetime, translations can also refer to changes in the time coordinate. For example, the Galilean group and the Poincaré group include translations with respect to time.

Lattice groups

One kind of subgroup of the three-dimensional translation group are the lattice groups, which are infinite groups, but unlike the translation groups, are finitely generated. That is, a finite generating set generates the entire group.

Matrix representation

A translation is an affine transformation with no fixed points. Matrix multiplications always have the origin as a fixed point. Nevertheless, there is a common workaround using homogeneous coordinates to represent a translation of a vector space with matrix multiplication: Write the 3-dimensional vector using 4 homogeneous coordinates as .[7]

To translate an object by a vector , each homogeneous vector (written in homogeneous coordinates) can be multiplied by this translation matrix:

As shown below, the multiplication will give the expected result:

The inverse of a translation matrix can be obtained by reversing the direction of the vector:

Similarly, the product of translation matrices is given by adding the vectors:

Because addition of vectors is commutative, multiplication of translation matrices is therefore also commutative (unlike multiplication of arbitrary matrices).

Translation of axes

While geometric translation is often viewed as an active process that changes the position of a geometric object, a similar result can be achieved by a passive transformation that moves the coordinate system itself but leaves the object fixed. The passive version of an active geometric translation is known as a translation of axes.

Translational symmetry

An object that looks the same before and after translation is said to have translational symmetry. A common example is a periodic function, which is an eigenfunction of a translation operator.

Applications

Vehicle dynamics

For describing vehicle dynamics (or movement of any rigid body), including ship dynamics and aircraft dynamics, it is common to use a mechanical model consisting of six degrees of freedom, which includes translations along three reference axes, as well as rotations about those three axes.

These translations are often called:

- Surge, translation along the longitudinal axis (forward or backwards)

- Sway, translation along the transverse axis (from side to side)

- Heave, translation along the vertical axis (to move up or down).

The corresponding rotations are often called:

- roll, about the longitudinal axis

- pitch, about the transverse axis

- yaw, about the vertical axis.

See also

References

- ↑ De Berg, Mark; Cheong, Otfried; Van Kreveld, Marc; Overmars (2008), Computational Geometry Algorithms and Applications, Berlin: Springer, p. 91, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-77974-2, ISBN 978-3-540-77973-5, https://books.google.com/books?id=tkyG8W2163YC&pg=PA91.

- ↑ Smith, James T. (2011), Methods of Geometry, John Wiley & Sons, p. 356, ISBN 9781118031032, https://books.google.com/books?id=B0khWEZmOlwC&pg=PA356.

- ↑ Faulkner, John R. (2014), The Role of Nonassociative Algebra in Projective Geometry, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, 159, American Mathematical Society, p. 13, ISBN 9781470418496, https://books.google.com/books?id=axIBBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA13.

- ↑ Dougherty, Edward R.; Astol, Jaakko (1999), Nonlinear Filters for Image Processing, SPIE/IEEE series on imaging science & engineering, 59, SPIE Press, p. 169, ISBN 9780819430335, https://books.google.com/books?id=4PV-sTF6qJQC&pg=PA169.

- ↑ Zill, Dennis; Wright, Warren S. (2009), Single Variable Calculus: Early Transcendentals, Jones & Bartlett Learning, p. 269, ISBN 9780763749651, https://books.google.com/books?id=0n0iPYKLo74C&pg=PA269.

- ↑ Edmund Taylor Whittaker (1988). A Treatise on the Analytical Dynamics of Particles and Rigid Bodies (Reprint of fourth edition of 1936 with foreword by William McCrea ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-521-35883-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=epH1hCB7N2MC&q=rigid+bodies+translation&pg=PA4.

- ↑ Richard Paul, 1981, Robot manipulators: mathematics, programming, and control : the computer control of robot manipulators, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Further reading

- Zazkis, R., Liljedahl, P., & Gadowsky, K. Conceptions of function translation: obstacles, intuitions, and rerouting. Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 22, 437-450. Retrieved April 29, 2014, from www.elsevier.com/locate/jmathb

- Transformations of Graphs: Horizontal Translations. (2006, January 1). BioMath: Transformation of Graphs. Retrieved April 29, 2014

External links

- Translation Transform at cut-the-knot

- Geometric Translation (Interactive Animation) at Math Is Fun

- Understanding 2D Translation and Understanding 3D Translation by Roger Germundsson, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

|