Biology:Retrospective memory

Retrospective memory is the memory of people, words, and events encountered or experienced in the past. It includes all other types of memory including episodic, semantic and procedural.[1] It can be either implicit or explicit. In contrast, prospective memory involves remembering something or remembering to do something after a delay, such as buying groceries on the way home from work. However, it is very closely linked to retrospective memory, since certain aspects of retrospective memory are required for prospective memory.

Relationship with prospective memory

Early research on prospective memory and retrospective memory has demonstrated that retrospective memory has a role in prospective memory. It was necessary to create more accurate terms in order to explain the relationship fully. Prospective memory describes more accurately an experimental paradigm, therefore, the term prospective remembering was subsequently used.[2] A review by Burgess and Shallice described studies where patients had impaired prospective memory, but intact retrospective memory, and also studies where the impaired retrospective memory caused an impact on prospective memory. A double dissociation for the two has not been found, therefore concluding they are not independent entities. The role of retrospective memory in prospective memory is suggested to be minimal, and takes the form of the information required to make plans. According to Einstein & McDaniel (1990) the retrospective memory component of the prospective remembering task refers to the ability to retain the basic information about action and context. An example used in the reviews explains this in the following scenario:

- You are intending to mail a letter on your way home tomorrow evening, at the mailbox that you have used before"

The basic information of the retrieval context includes time, location and objects, which in combination form the required retrieval context. Each individual representation required is a form of retrospective memory.[2] Despite all the research this issue is still debatable within the scientific community.

Episodic memory

Retrospective episodic memory is recollection of past episodes. Significant research in this field looks at the phenomenon of mental time travel.

Mental time travel

Mental time travel (MTT) is defined as the ability to mentally project oneself backwards in time to re-live past personal experiences, or forward in time to pre-live possible events in the future.[3] It is a concept created by Canadian psychologist Endel Tulving. It does not simply refer to knowing an event happened, but requires conscious awareness that the individual is indeed reliving the episode. Due to this, it is certain that mental time travel requires central executive functioning, and most often a conscious ability. However new research has found many cases in which mental time travel occurs involuntarily without consciousness. Specifically research shows this occurs for autobiographical events, and as a result these cases are more specific and detail oriented. An example of this would be the phenomenon of scent: How a particular scent can send an individual back to a specific event in their lifetime. There is also evidence that involuntary and voluntary mental time travel differ on activation levels in areas of the brain suggesting that they have different retrieval mechanisms.[4] Current research has moved away from the retrospective portion and towards the prospective aspect of mental time travel. There is also extensive research on whether mental time travel is unique to humans as there has been some evidence that it may be possible to occur in animals[4][5]

Episodic

Retrospective episodic memory is the memory of moments from the past. It is frequently used in studies of Alzheimer patients and testing their dementia. A study by Livner et al. (2009) compared the effect of the disease on both prospective and retrospective memory. In this case the episodic memory being tested was the ability to remember the testing instructions. To test retrospective memory participants were presented with a list of nouns that had been divided into four categories. The results of retrospective memory were divided into three sections: number of categories, number of items remembered and forgetting ratio, in order to look at the three separate process in creating memory (encoding, retrieval, storage). Using their results and knowledge of episodic memory the researchers were able to find a pattern of functional impairments in the brain.[6]

Autobiographical

Retrospective autobiographical memory is recalling specific events from your own past. Testing of this type of memory has been used when researching the effect of emotion and context on memory. Abenavoli and Henkel (2009) conducted a study looking at childhood events, context and metamemory. They wanted to see if the participants memory of remembering childhood events was accurate. The results showed that when context was recreated metamemory improved as did vividness of the actual event. Besides these topics, it is also used in studying mental time travel and age-related factors.[7]

Semantic memory

Retrospective semantic memory refers to the collection of knowledge, meaning and concepts that have been acquired over time. [1] It plays a significant role in the study of priming. Jones (2010) researched a pure mediated priming effect and wanted to discover which model accounted for it. Pure priming refers to the connection between two concepts that have a weak or no association with each other. Each of three potential models (spreading activation, compound-cue and semantic matching) were tested with the results concluding that retrospective semantic matching model creates the pure priming effect. This study shows pure priming has more applications than previously thought.[8]

Retrograde amnesia

Retrograde amnesia is defined as the loss of memory of events and experiences occurring prior to an illness, accident, injury, or traumatic experience such as rape or assault. The amnesia may cover events over a longer or only a brief period. Typically, it declines with time, with earlier memories returning first.[9] There are many possible causes of amnesia. The most common include Alzheimer's disease, traumatic brain injury, brain infection (such as encephalitis or meningitis), dementia, seizures, and stroke. Less common causes include a brain tumor or psychiatric disorders (schizophrenia, depression, criminal behavior, or psychogenic amnesia). Psychogenic amnesia usually happens in close association with a stressful event that involves serious threat to life or health. There are two types of retrograde amnesia, one dealing with episodic memory, and one dealing with semantic memory. Semantic retrograde amnesia involves loss of generic, lifelong knowledge, as in the various forms of aphasia or agnosia, and also loss of learned motor skills, as in the various types of apraxia. Its primary focus is on retrograde amnesia for specific, usually time-limited, knowledge. In the case of semantic retrograde amnesia, memory for public events and memory for people have formed the primary corpus of research.[10]

Neuroanatomy

Medial prefrontal cortex

A study was conducted by Kesner (1989)[11] on retrospective memory involving rats. Lesions made to the medial prefrontal cortex of rats led to impairment of retrospective memory, as well as strong impairment to prospective memory on a radial arm task.

Medial temporal lobe

Different brain regions in the medial temporal lobe play a unique role in memory. The medial temporal lobe seems to function as a memory system for consciously available events and facts, and is important for the acquisition of new episodic and semantic memory. There is also evidence that the medial temporal lobe automatically encodes memories.[12]

The role of the medial temporal lobe for retrospective memory was assessed by Okuda et al. (2003)[13] using Positron Emission Tomography (PET). The PET found that thinking about past events increased blood flow to the medial temporal lobes, emphasizing that this brain area contributes to the activation of retrospective memory. Also, the medial temporal lobe displayed activation levels associated with prospective memories. This finding gives support for the belief that thinking about the future to an extent relies upon thinking about the past, showing a close relationship between retrospective memory and prospective memory.

Hippocampus

The hippocampus plays an important role for remembering specific personal experiences in humans, as well as memory for sequence of events.[14]

A series of lesion studies assessed the role of the hippocampus on retrospective memory. In the first delayed response task, nonhuman primates were shown two food wells. For the primates to get a reward, they had to remember which food well was baited. However, the primate had to retain the information about the two prospects until an apparatus was lowered and raised after a delay interval. The results showed that lesions to the hippocampus impaired performance on this task. In a variation of the study, the primates were required to approach the food well that was empty after a delay. It was found that damage to the thalamus also caused impaired performance on both tasks, but at longer delay intervals. These studies confirmed that damage to the hippocampus and thalamus impaired the recall for episodic memory of previously experienced events.[15]

In a lesion study involving rats, Ferbinteanu and Shapiro (2003)[16] found the importance of the hippocampus for correctly remembering past events. In the study, rats with fornix lesions displayed poor choice accuracy in a spatial task requiring memory for temporal context, which was seen as evidence for impaired retrospective memory.

In an earlier study, Kametani and Kesner (1989)[17] found that rats with lesions in the hippocampus made a large number of errors on a radial arm maze, indicating impaired retrospective memory for points of interpolation within the maze.

Thalamus

It is known that the thalamus plays a crucial role in memory.[18]

While investigating stroke-patients with damage to the thalamus, Cipolotti et al. (2008)[19] found that the stroke victims had poor recognition and recall memory on verbal and non-verbal tests. The poor recall identified that the retrospective memory of the patients was being effected by the damage on the thalamus due to stroke.

Lesions to the thalamus have been found to impair the recognition memory of monkeys. In a study conducted by Aggleton and Mishkin, they found that monkeys with lesions to the anterior thalamus and the posterior thalamus had an impaired ability for recognition and associative memory on matching tests. The researchers also suggested that combined damage to both regions of the thalamus can lead to amnesia.[20]

Amygdala

The amygdala plays a special role in that it is crucial to the emotional aspect of retrospective memory. It is responsible for the encoding of emotionally laden events, and there is evidence that memories for emotional events are more vivid than other memories.[21]

The amygdala has been associated with memories for past emotional events. A number of studies have provided evidence that the amygdala acts as an intermediate for emotionally influenced memory. These studies have investigated lesions of the amygdala in animals and humans.[22]

Imaging studies have shown that amygdala activation is associated with emotional memory, and that past emotional memories are often better remembered than neutral memories. It has also been seen that the amygdala enhances memory in relation to the intensity of emotion in past experience, as well as enhancing declarative memory for emotional experiences.[23]

Hamann et al. (1999)[24] also found that emotional events (both pleasant and aversive) are better remembered than neutral events. They went on to find that the amygdala plays a crucial role for enhancing the strength of long-term and episodic memory. Using PET, the amygdala was shown to be responsible for enhanced episodic memory in the recognition of emotional stimuli.

Measures of assessment

PRMQ

The Prospective/Retrospective Memory Questionnaire (PRMQ) was developed by Smith et al. in order to study Alzheimer patients.[25] It is a 16-item questionnaire on which participants indicate the frequency in which they make certain memory errors. They use a 5-point scale (Very Often, Quite Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never). Categories tested include prospective short term and long term, as well as retrospective short term and long-term memory. It is different from previous questionnaires because it has the ability to compare prospective and retrospective memory across several conditions. Since its creation, it has been used in numerous studies to look at the effects of Alzheimer's disease on prospective memory and retrospective memory.

MET/SET

- MET or Multiple Errands test

- Participants are given a set of shopping activities that must be completed in real time in a shopping area. Certain aspects, such as remembering to be in a specific place at a specific time, involve prospective memory. Other aspects such as remembering the exact activity involve retrospective memory. By looking at the performance of the participants at certain tasks, the experimenters can determine the effects of prospective and retrospective memory on each other.[26]

- SET or the Six Element test

- Participants are given six open-ended tasks that must be completed in 15 minutes. Two of these tasks require dictating a route, two involve writing down the names of pictures of objects, and two ask the participant to complete a series of math problems. There is not enough time to complete all the tasks, therefore the participant is required to allocate appropriate timing to each task. Aspects of the test that show the effects of retrospective memory include remembering that they had created an order in which to do the tasks.[2]

Classic short term memory tests

- Digit span

- A test for short-term retrospective memory. Participants are presented verbally with a list of digits. They are subsequently asked to recall them in the order they were presented.

- Free recall

- A test for short-term retrospective memory. Participants are presented with a sequence of items and are subsequently asked to recall them in any order.

- Word recall

- Similar to free recall; instead of digits, words are substituted.

- Facial recognition

- A test for short term retrospective memory. Participants are presented with images of faces and subsequently asked to recall them at a later period.[1]

Issues in testing

Often involve testing both prospective and retrospective memory; sometimes difficult to isolate one. Additionally, Mantyla (2003) compared the results of the PRMQ to word recall tests of RM and found that they did not match. In this study retrospective memory performance did not match retrospective memory scores on PRMQ.[27]

Factors affecting retrospective memory

Age

Age is a significant factor that effects memory. There is tremendous evidence that infants can learn and remember. However, infantile amnesia is an important, yet difficult area to study. Events from infancy simply cannot be remembered. Many studies have tried and failed to determine the cause of this. Consequently, many theories have been developed to explain this phenomenon.[28] These theories range from the Freudian psychodynamic theory that remembering events from infancy would be damaging to the "ego", to theories that explain the underdeveloped hippocampus of an infant, and also theories that conclude that infants have not yet developed autonoetic consciousness of having experienced remembered events.[29] This theory relies on Tulving's view of episodic memory.

Three studies were conducted to examine the differences in specificity at retrieval between younger adults (age range: 19–25 years, mean = 21.5 years), and older adults (age range: 64–82 years, mean = 74.1 years). It was found that older adults had lower retrieval for high specificity tests, but not for low specificity. And it was also found that the effects of divided attention on retrieval of younger adults mimicked the effects of aging. Therefore, retrieval efficiency depends on effortful, resource-demanding retrieval processes that is diminished in older adults.[30]

As we age, the ventricles in the brain get larger as our brains get smaller. Functional changes do not normally depend on total brain size, but rather which part of the brain is getting smaller. The frontal lobes usually shrink more quickly, and the temporal and occipital lobes are slower. 20–30% of neurons in the hippocampus (which plays a critical role in memory) are lost by the age of 80.[1] It has also been found that dopamine levels decrease by 5–10% per decade. This neurotransmitter plays a critical role in neural cognition (decrease associated with Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease).[1]

Sex

Some differences in memory performance have been observed between men and women. A series of experiments revealed that women did better at verbal episodic memory tasks (ex. remembering words, objects, pictures and everyday events), tasks with both verbal and visuospatial processing (ex. remembering the location of car keys), and tasks requiring little to no verbal processing (ex. recognition of familiar odours). Men, on the other hand, were better at purely visuospatial processing (ex. remembering symbolic or non-linguistic information). All of these differences may vary due to environmental factors such as education.[31]

Trauma

Emotional

It has been found that even though memory usually declines with age, elderly people tend to remember more positive memories than negative or even neutral ones. As we grow older, we focus more on positive things and start to develop the skill of emotion regulation which is "monitoring, evaluating, altering and gating one's emotional reactions and memories about emotional experiences".[1] This is also referred to as motivated forgetting.[1]

An unusual form of motivated forgetting is called psychogenic amnesia in which a very severe emotional stressor causes one to lose a large amount of personal memories without an observable biological cause.[1] Another reaction to a very severe stressor is called post traumatic stress disorder. People who have been subject to a traumatic event that has included death of others or a possibility of death or severe injury to oneself cannot forget these memories. This sometimes leads to flashbacks and nightmares that cause people to re-live these traumatic events for long periods afterwards.[32]

Miron-Shatz et al. looked at life as we actually live it and the differences that emerge when recalling it. The goal was to discover if there are qualitative differences for remembering pleasant versus unpleasant events. It was discovered that gaps occur for both pleasant and unpleasant events; however they were more pronounced for unpleasant events, meaning pleasant events were recalled as neutral events, but unpleasant events were recalled at extremely unpleasant. These findings support the notion that unpleasant events have a stronger impact on our recall.[33]

Physical

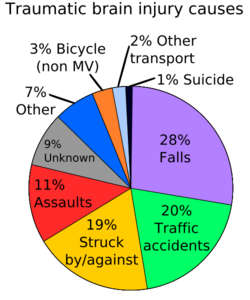

Traumatic brain injury happens when the head suffers from a sharp blow, or suddenly accelerates or decelerates. In these cases, the brain gets churned around, and can be damaged by the bony bumps and knobs inside the skull, or by the twisting and tearing of fibres in the brain.[1] If the traumatic brain injury is severe enough, it can lead to an initial coma, which is then followed by a time of post-traumatic amnesia. Post traumatic amnesia typically resolves itself gradually, however it will leave a mild, but permanent deficit in the patient's memory.[1]

Lesions to certain areas of the brain may lead to cognitive and memory deficits – see Neuroanatomy section above.

Drugs

A study by de Win et al. used advanced magnetic resonance and SPECT (single photon emission computed tomography) imaging techniques on the same sample study to determine if any functional differences appear in the brains of MDMA users. It is almost impossible to find purely MDMA users (without the use of cannabis, cocaine or other amphetamines), but with statistical analysis, it was found that MDMA has specific serotonergic damaging effects on the thalamus. This damage was speculated to be axonal damage to serotonergic cells while cell bodies remained intact. This damage is at least partly responsible for the commonly found reduced verbal memory in users.[34]

Conflicting results have been found by many studies that have looked at brain anatomy in frequent marijuana users. The goal is to determine whether or not marijuana has any effects on cognitive abilities (including memory). A study done by Jager et al. concluded that there are in fact anatomical differences between the brains of frequent marijuana users and non-using control samples. Frequent users showed a lower magnitude of activity (but no structural changes) in parahippocampal regions. However, when subject to associative memory tasks, users performed within normal ranges. This shows that a decrease in activation in these regions is associated with frequent marijuana use, but does not affect memory task performance.[35] This is still a controversial issue, and more research is required to draw conclusive results.

Disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VaD)

Alzheimer's disease accounts for 60 to 70 percent of cases of dementias. The brains of Alzheimer's patients have an abundance of plaques and tangles which begin in areas involved in memory, spreading to other areas, and eventually affecting most of the brain. Vascular dementia is often considered the second-most common form of dementia and is the reduction of blood flow to parts of the brain most often caused by many very small strokes that have an accumulative effect on cognitive abilities including memory.[36][37]

Korsakoff's syndrome

Korsakoff's is caused by a severe thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency due to chronic alcoholism or malnourishment. Thiamine is necessary for the body to process carbohydrates. This thiamine deficiency can lead to symptoms such as: confusion, loss of balance, drowsiness, and some specific problems with vision. When the deficiency is considered severe, the memory loss may be accompanied by agitation and dementia. The standard treatment is intravenous thiamine, administered as soon as possible after symptoms become apparent. Unfortunately, the treatment does not correct the condition and recovery is known to be gradual and sometimes incomplete. Temporally graded retrograde amnesia extending back several decades (early memories in life) are a common feature of patients with the alcoholic Korsakoff's syndrome, which primarily affects the diencephalon, usually with concomitant frontal lobe atrophy.[38]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Baddeley, A., Eysenck, M.W. & Anderson, M.C. (2009) "Memory". New York: Psychology Press.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Burgess, P.W. & Shallice, T.(1997)The relationship between prospective and retrospective memory: neuropsychological evidence. In Conway, M.A. (Ed.), Cognitive Models of Memory(247-272). Cambridge: MIT Press.

- ↑ Wheeler, M. A., Stuss, D. T., & Tulving, E. (1997). Toward a theory of episodic memory: The frontal lobes and autonoetic consciousness. Psychological Bulletin,121,331–354.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Bernsten, D. & Jacobsen, A.S. (2008). Involuntary (spontaneous) mental time travel into the past and future. Consciousness and Cognition, 17 1093-1004.

- ↑ Mendi, M. & Paul, E.S.(2008). Do animals live in the present? Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 113,(4), 357-382.

- ↑ Livner, A, Laukka, E.J., Karlsson, S. & Backman, L. (2009). Prospective and retrospective memory in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia: Similar patterns of impairment. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 283, 235-2009.

- ↑ Abenavoli, R. & Henkel, L.A. (2009). Remembering When We Last Remembered Our Childhood Experiences: Effects of Age and Context on Retrospective Metamemory Judgements. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23, 717-732.

- ↑ Jones, L.J. (2010). Pure Mediated Priming: A Retrospective Semantic Search Model. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36(1), 135-146.

- ↑ Gordon, M. Retrograde amnesia." A Dictionary of Sociology. 1998. Retrieved March 04, 2010 from Encyclopedia.com: http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O88-retrogradeamnesia.html

- ↑ Kapur, N. (1999). Syndromes of retrograde amnesia: a conceptual and empirical synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), 800-825.

- ↑ Kesner, R.P. (1989). Retrospective and prospective coding of information: role of the medial prefrontal cortex. Experimental Brain Research, 74, 163-167.

- ↑ Graham, K.S., & Gaffan, D. (2005). The quarterly journal of experimental psychology. New York, NY: Psychology Press, Ltd.

- ↑ Okuda, J., Fujii, T., Ohtake, H., Tukiura, T., Tanji, K., Suzuki, K., et al. (2003). Thinking of the future and the past: the roles of the frontal pole and the medial temporal lobes. Neuroimage, 19, 1369-1380.

- ↑ Fortin, N.J., Agster, K.L., & Eichenbaum, H.B. (2002). Critical role of the hippocampus in memory for sequences of events. Nature Neuroscience, 5(5), 458-562.

- ↑ Risberg, J. & Grafman, J. (Ed.). (2006). The frontal lobes: Development, function and pathology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Ferbinteanu, J., & Shapiro, M.L. (2003) Prospective and retrospective memory coding in the hippocampus. Neuron, 40, 1227-1239.

- ↑ Kametani, H., & Kesner, R.P. (1989). Retrospective and prospective coding of information: dissociation of parietal cortex and hippocampal formation. Behavioural Neuroscience, 103(1), 84-89.

- ↑ Cheng, H., Tian, Y., Hu, P., Wang, J., & Wang, K. (2010). Time-based prospective memory impairment with thalamus stroke. Behavioral Neuroscience, 124(1), 152-58.

- ↑ Cipolotti, L., Husain, M., Crinion, J., Bard, C.M., Khan, S.S., et al. (2008). The role of the thalamus in amnesia: a tractography, high-resolution MRI and neuropsychological study. Neuropsychologia, 46, 2745-2758.

- ↑ Aggleton, J.P., & Mishkin, M. (1983). Memory impairments following restricted medial thalamic lesions in monkeys. Experimental Brain Research. 52, 199-209.

- ↑ Phelps, E.A. (2004). Human emotion and memory: Interactions of the amygdala and hippocampal complex. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, (14), 198-202.

- ↑ McGaugh, J.L., Cahill, L. and Roozendaal, B. (1996). Involvement of the amygdala in memory storage: Interaction with other brain systems. National Academy of Sciences, (93) 24, 13508-13514.

- ↑ Canli, T., Zhao, Z., Brewer, J., Gabrieli, J.D.E., Cahill, L. (2000). Event-related activation in the human amygdala associates with later memory for individual emotional experience. The Journal of Neuroscience,(20), 1-5.

- ↑ Hamann, S.B., Ely, T.D., Grafton, S.T., Kilts, C.D. (1999). Amygdala activity related to enhanced memory for pleasant and aversive stimuli. Nature Neuroscience, (2) 3, 289-293.

- ↑ Smith, G., Della Sala, S., Logie, R.H. & Maylor, E.A. (2000). Prospective and retrospective memory in normal ageing and dementia: A questionnaire study. Memory,8(5), 311-321.

- ↑ Shallice, T. & Burgess P.W. (1991). Higher order cognitive impairments and frontal lobe lesions in man. In Levin, H.S., Eisenberg, H.M. & Benton, A.L.(Eds.), "Frontal lobe function and injury" (125-138). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Mantyla, T. (2003). Assessing absentmindedness: Prospective memory complaint and impairment in middle-aged adults. "Memory and Cognition,31, 15-25.

- ↑ Kail, R., Spear, N.E. Comparative Perspectives on the Development of Memory. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., 1984.

- ↑ Perner J. and Ruffman T. Episodic Memory and Autonoetic Consciousness: Developmental Evidence and a Theory of Childhood Amnesia. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 59 (3), 516-548.

- ↑ Lin Luo *, Fergus I.M. Craik. 2009. Age differences in recollection: Specificity effects at retrieval. Journal of Memory and Language, 60 (4), 421-436.

- ↑ Herlitz, A. & Rehnman, J. 2008. Sex Differences in Episodic Memory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17 (1), 52–56.

- ↑ Canadian Mental Health Association. (2010) Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Retrieved from http://www.cmha.ca/bins/content_page.asp?cid=3-94-97

- ↑ Miron-Shatz, T., Stone, A., Kahnemana, D. (2009) Memories of Yesterday's Emotions: Does the Valence of Experience Affect the Memory-Experience Gap? Emotion 9(6): 885-891.

- ↑ de Win, M.M.L., Jager, G., Booij, J., Reneman, L., Schilt, T., Lavini, C., Olabarriaga, S.D., Ramsey, N.F., den Heeten, G.J., and van den Brink, W.(2008) Neurotoxic effects of ecstasy on the thalamus. The British Journal of Psychiatry 193(4): p. 289-296.

- ↑ Jager, G., Van Hella, H.H., de Win, M.M.L., Kahna, R.S., Van Den Brink, W., Van Reed, J.M., and Ramsey, N.F. (2007) Effects of frequent cannabis use on hippocampal activity during an associative memory task. European Neuropsychopharmacology 17(4): 289-297

- ↑ Alzheimer's Association. (2005) "Basics of Alzheimer's Disease: What it is and what you can do." Retrieved from http://www.alz.org/national/documents/brochure_basicsofalz_low.pdf

- ↑ Alzheimer's Association. (2010) "What is Alzheimer's?" Retrieved from http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_what_is_alzheimers.asp

- ↑ Verfaellie, M. (2009). Remote semantic memories in patients with korsakoff's syndrome and herpes encephalitis. Neuropsychology, 23(2)

- Einstein, G.O. & McDaniel, M.A. (1990). Normal ageing and prospective memory.