Dynamic array

In computer science, a dynamic array, growable array, resizable array, dynamic table, mutable array, or array list is a random access, variable-size list data structure that allows elements to be added or removed. It is supplied with standard libraries in many modern mainstream programming languages. Dynamic arrays overcome a limit of static arrays, which have a fixed capacity that needs to be specified at allocation.

A dynamic array is not the same thing as a dynamically allocated array or variable-length array, either of which is an array whose size is fixed when the array is allocated, although a dynamic array may use such a fixed-size array as a back end.[1]

Bounded-size dynamic arrays and capacity

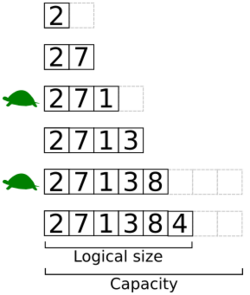

A simple dynamic array can be constructed by allocating an array of fixed-size, typically larger than the number of elements immediately required. The elements of the dynamic array are stored contiguously at the start of the underlying array, and the remaining positions towards the end of the underlying array are reserved, or unused. Elements can be added at the end of a dynamic array in constant time by using the reserved space, until this space is completely consumed. When all space is consumed, and an additional element is to be added, then the underlying fixed-size array needs to be increased in size. Typically resizing is expensive because it involves allocating a new underlying array and copying each element from the original array. Elements can be removed from the end of a dynamic array in constant time, as no resizing is required. The number of elements used by the dynamic array contents is its logical size or size, while the size of the underlying array is called the dynamic array's capacity or physical size, which is the maximum possible size without relocating data.[2]

A fixed-size array will suffice in applications where the maximum logical size is fixed (e.g. by specification), or can be calculated before the array is allocated. A dynamic array might be preferred if:

- the maximum logical size is unknown, or difficult to calculate, before the array is allocated

- it is considered that a maximum logical size given by a specification is likely to change

- the amortized cost of resizing a dynamic array does not significantly affect performance or responsiveness

Geometric expansion and amortized cost

To avoid incurring the cost of resizing many times, dynamic arrays resize by a large amount, such as doubling in size, and use the reserved space for future expansion. The operation of adding an element to the end might work as follows:

function insertEnd(dynarray a, element e)

if (a.size == a.capacity)

// resize a to twice its current capacity:

a.capacity ← a.capacity * 2

// (copy the contents to the new memory location here)

a[a.size] ← e

a.size ← a.size + 1

As n elements are inserted, the capacities form a geometric progression. Expanding the array by any constant proportion a ensures that inserting n elements takes O(n) time overall, meaning that each insertion takes amortized constant time. Many dynamic arrays also deallocate some of the underlying storage if its size drops below a certain threshold, such as 30% of the capacity. This threshold must be strictly smaller than 1/a in order to provide hysteresis (provide a stable band to avoid repeatedly growing and shrinking) and support mixed sequences of insertions and removals with amortized constant cost.

Dynamic arrays are a common example when teaching amortized analysis.[3][4]

Growth factor

The growth factor for the dynamic array depends on several factors including a space-time trade-off and algorithms used in the memory allocator itself. For growth factor a, the average time per insertion operation is about a/(a−1), while the number of wasted cells is bounded above by (a−1)n[citation needed]. If memory allocator uses a first-fit allocation algorithm, then growth factor values such as a=2 can cause dynamic array expansion to run out of memory even though a significant amount of memory may still be available.[5] There have been various discussions on ideal growth factor values, including proposals for the golden ratio as well as the value 1.5.[6] Many textbooks, however, use a = 2 for simplicity and analysis purposes.[3][4]

Below are growth factors used by several popular implementations:

| Implementation | Growth factor (a) |

|---|---|

| Java ArrayList[1] | 1.5 (3/2) |

| Python PyListObject[7] | ~1.125 (n + (n >> 3)) |

| Microsoft Visual C++ 2013[8] | 1.5 (3/2) |

| G++ 5.2.0[5] | 2 |

| Clang 3.6[5] | 2 |

| Facebook folly/FBVector[9] | 1.5 (3/2) |

| Rust Vec[10] | 2 |

| Go slices[11] | between 1.25 and 2 |

| Nim sequences[12] | 2 |

| SBCL (Common Lisp) vectors[13] | 2 |

Performance

| Linked list | Array | Dynamic array | Balanced tree | Random access list | Hashed array tree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indexing | Θ(n) | Θ(1) | Θ(1) | Θ(log n) | Θ(log n)[14] | Θ(1) |

| Insert/delete at beginning | Θ(1) | N/A | Θ(n) | Θ(log n) | Θ(1) | Θ(n) |

| Insert/delete at end | Θ(1) when last element is known; Θ(n) when last element is unknown |

N/A | Θ(1) amortized | Θ(log n) | Θ(log n) updating | Θ(1) amortized |

| Insert/delete in middle | search time + Θ(1)[15][16] | N/A | Θ(n) | Θ(log n) | Θ(log n) updating | Θ(n) |

| Wasted space (average) | Θ(n) | 0 | Θ(n)[17] | Θ(n) | Θ(n) | Θ(√n) |

The dynamic array has performance similar to an array, with the addition of new operations to add and remove elements:

- Getting or setting the value at a particular index (constant time)

- Iterating over the elements in order (linear time, good cache performance)

- Inserting or deleting an element in the middle of the array (linear time)

- Inserting or deleting an element at the end of the array (constant amortized time)

Dynamic arrays benefit from many of the advantages of arrays, including good locality of reference and data cache utilization, compactness (low memory use), and random access. They usually have only a small fixed additional overhead for storing information about the size and capacity. This makes dynamic arrays an attractive tool for building cache-friendly data structures. However, in languages like Python or Java that enforce reference semantics, the dynamic array generally will not store the actual data, but rather it will store references to the data that resides in other areas of memory. In this case, accessing items in the array sequentially will actually involve accessing multiple non-contiguous areas of memory, so the many advantages of the cache-friendliness of this data structure are lost.

Compared to linked lists, dynamic arrays have faster indexing (constant time versus linear time) and typically faster iteration due to improved locality of reference; however, dynamic arrays require linear time to insert or delete at an arbitrary location, since all following elements must be moved, while linked lists can do this in constant time. This disadvantage is mitigated by the gap buffer and tiered vector variants discussed under Variants below. Also, in a highly fragmented memory region, it may be expensive or impossible to find contiguous space for a large dynamic array, whereas linked lists do not require the whole data structure to be stored contiguously.

A balanced tree can store a list while providing all operations of both dynamic arrays and linked lists reasonably efficiently, but both insertion at the end and iteration over the list are slower than for a dynamic array, in theory and in practice, due to non-contiguous storage and tree traversal/manipulation overhead.

Variants

Gap buffers are similar to dynamic arrays but allow efficient insertion and deletion operations clustered near the same arbitrary location. Some deque implementations use array deques, which allow amortized constant time insertion/removal at both ends, instead of just one end.

Goodrich[18] presented a dynamic array algorithm called tiered vectors that provides O(n1/k) performance for insertions and deletions from anywhere in the array, and O(k) get and set, where k ≥ 2 is a constant parameter.

Hashed array tree (HAT) is a dynamic array algorithm published by Sitarski in 1996.[19] Hashed array tree wastes order n1/2 amount of storage space, where n is the number of elements in the array. The algorithm has O(1) amortized performance when appending a series of objects to the end of a hashed array tree.

In a 1999 paper,[17] Brodnik et al. describe a tiered dynamic array data structure, which wastes only n1/2 space for n elements at any point in time, and they prove a lower bound showing that any dynamic array must waste this much space if the operations are to remain amortized constant time. Additionally, they present a variant where growing and shrinking the buffer has not only amortized but worst-case constant time.

Bagwell (2002)[20] presented the VList algorithm, which can be adapted to implement a dynamic array.

Naïve resizable arrays -- also called "the worst implementation" of resizable arrays -- keep the allocated size of the array exactly big enough for all the data it contains, perhaps by calling realloc for each and every item added to the array. Naïve resizable arrays are the simplest way of implementing a resizeable array in C. They don't waste any memory, but appending to the end of the array always takes Θ(n) time.[19][21][22][23][24] Linearly growing arrays pre-allocate ("waste") Θ(1) space every time they re-size the array, making them many times faster than naïve resizable arrays -- appending to the end of the array still takes Θ(n) time but with a much smaller constant. Naïve resizable arrays and linearly growing arrays may be useful when a space-constrained application needs lots of small resizable arrays; they are also commonly used as an educational example leading to exponentially growing dynamic arrays.[25]

Language support

C++'s std::vector and Rust's std::vec::Vec are implementations of dynamic arrays, as are the ArrayList[26] classes supplied with the Java API[27]:236 and the .NET Framework.[28][29]:22

The generic List<> class supplied with version 2.0 of the .NET Framework is also implemented with dynamic arrays. Smalltalk's OrderedCollection is a dynamic array with dynamic start and end-index, making the removal of the first element also O(1).

Python's list datatype implementation is a dynamic array the growth pattern of which is: 0, 4, 8, 16, 24, 32, 40, 52, 64, 76, ...[30]

Delphi and D implement dynamic arrays at the language's core.

Ada's Ada.Containers.Vectors generic package provides dynamic array implementation for a given subtype.

Many scripting languages such as Perl and Ruby offer dynamic arrays as a built-in primitive data type.

Several cross-platform frameworks provide dynamic array implementations for C, including CFArray and CFMutableArray in Core Foundation, and GArray and GPtrArray in GLib.

Common Lisp provides a rudimentary support for resizable vectors by allowing to configure the built-in array type as adjustable and the location of insertion by the fill-pointer.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 See, for example, the source code of java.util.ArrayList class from OpenJDK 6.

- ↑ Lambert, Kenneth Alfred (2009), "Physical size and logical size", Fundamentals of Python: From First Programs Through Data Structures (Cengage Learning): p. 510, ISBN 978-1423902188, https://books.google.com/books?id=VtfM3YGW5jYC&q=%22logical+size%22+%22dynamic+array%22&pg=PA518

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Goodrich, Michael T.; Tamassia, Roberto (2002), "1.5.2 Analyzing an Extendable Array Implementation", Algorithm Design: Foundations, Analysis and Internet Examples, Wiley, pp. 39–41.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2001) [1990]. "17.4 Dynamic tables". Introduction to Algorithms (2nd ed.). MIT Press and McGraw-Hill. pp. 416–424. ISBN 0-262-03293-7.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "C++ STL vector: definition, growth factor, member functions". http://www.gahcep.com/cpp-internals-stl-vector-part-1/.

- ↑ "vector growth factor of 1.5". Google Groups. https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/comp.lang.c++.moderated/asH_VojWKJw%5B1-25%5D.

- ↑ List object implementation from github.com/python/cpython/, retrieved 2020-03-23.

- ↑ Brais, Hadi. "Dissecting the C++ STL Vector: Part 3 - Capacity & Size". https://hadibrais.wordpress.com/2013/11/15/dissecting-the-c-stl-vector-part-3-capacity/.

- ↑ "facebook/folly". https://github.com/facebook/folly/blob/master/folly/docs/FBVector.md.

- ↑ "rust-lang/rust" (in en). https://github.com/rust-lang/rust/blob/fd4b177aabb9749dfb562c48e47379cea81dc277/src/liballoc/raw_vec.rs#L443.

- ↑ "golang/go". https://github.com/golang/go/blob/master/src/runtime/slice.go#L188.

- ↑ "The Nim memory model". http://zevv.nl/nim-memory/#_growing_a_seq.

- ↑ "sbcl/sbcl". https://github.com/sbcl/sbcl/blob/master/src/code/array.lisp#L1200-L1204.

- ↑ Chris Okasaki (1995). "Purely Functional Random-Access Lists". Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Functional Programming Languages and Computer Architecture: 86-95. doi:10.1145/224164.224187.

- ↑ Day 1 Keynote - Bjarne Stroustrup: C++11 Style at GoingNative 2012 on channel9.msdn.com from minute 45 or foil 44

- ↑ Number crunching: Why you should never, ever, EVER use linked-list in your code again at kjellkod.wordpress.com

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Brodnik, Andrej; Carlsson, Svante; Sedgewick, Robert; Munro, JI; Demaine, ED (1999), Resizable Arrays in Optimal Time and Space (Technical Report CS-99-09), Department of Computer Science, University of Waterloo, http://www.cs.uwaterloo.ca/research/tr/1999/09/CS-99-09.pdf Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "brodnik" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Goodrich, Michael T.; Kloss II, John G. (1999), "Tiered Vectors: Efficient Dynamic Arrays for Rank-Based Sequences", Workshop on Algorithms and Data Structures, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 1663: 205–216, doi:10.1007/3-540-48447-7_21, ISBN 978-3-540-66279-2, https://archive.org/details/algorithmsdatast0000wads/page/205

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Sitarski, Edward (September 1996), "HATs: Hashed array trees", Dr. Dobb's Journal 21 (11), http://www.ddj.com/architect/184409965?pgno=5

- ↑ Bagwell, Phil (2002), Fast Functional Lists, Hash-Lists, Deques and Variable Length Arrays, EPFL, http://citeseer.ist.psu.edu/bagwell02fast.html

- ↑ Mike Lam. "Dynamic Arrays".

- ↑ "Amortized Time".

- ↑ "Hashed Array Tree: Efficient representation of Array".

- ↑ "Different notions of complexity".

- ↑ Peter Kankowski. "Dynamic arrays in C".

- ↑ Javadoc on

ArrayList - ↑ Bloch, Joshua (2018). "Effective Java: Programming Language Guide" (third ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0134685991.

- ↑ ArrayList Class

- ↑ Skeet, Jon. C# in Depth. Manning. ISBN 978-1617294532.

- ↑ listobject.c (github.com)

External links

- NIST Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures: Dynamic array

- VPOOL - C language implementation of dynamic array.

- CollectionSpy — A Java profiler with explicit support for debugging ArrayList- and Vector-related issues.

- Open Data Structures - Chapter 2 - Array-Based Lists, Pat Morin

|