Queue (abstract data type)

| Queue | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Time complexity in big O notation | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

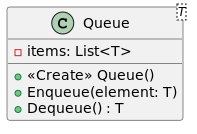

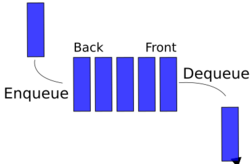

In computer science, a queue is a collection of entities that are maintained in a sequence and can be modified by the addition of entities at one end of the sequence and the removal of entities from the other end of the sequence. By convention, the end of the sequence at which elements are added is called the back, tail, or rear of the queue, and the end at which elements are removed is called the head or front of the queue, analogously to the words used when people line up to wait for goods or services.

The operation of adding an element to the rear of the queue is known as enqueue, and the operation of removing an element from the front is known as dequeue. Other operations may also be allowed, often including a peek or front operation that returns the value of the next element to be dequeued without dequeuing it.

The operations of a queue make it a first-in-first-out (FIFO) data structure. In a FIFO data structure, the first element added to the queue will be the first one to be removed. This is equivalent to the requirement that once a new element is added, all elements that were added before have to be removed before the new element can be removed. A queue is an example of a linear data structure, or more abstractly a sequential collection. Queues are common in computer programs, where they are implemented as data structures coupled with access routines, as an abstract data structure or in object-oriented languages as classes. Common implementations are circular buffers and linked lists.

Queues provide services in computer science, transport, and operations research where various entities such as data, objects, persons, or events are stored and held to be processed later. In these contexts, the queue performs the function of a buffer. Another usage of queues is in the implementation of breadth-first search.

Queue implementation

Theoretically, one characteristic of a queue is that it does not have a specific capacity. Regardless of how many elements are already contained, a new element can always be added. It can also be empty, at which point removing an element will be impossible until a new element has been added again.

Fixed-length arrays are limited in capacity, but it is not true that items need to be copied towards the head of the queue. The simple trick of turning the array into a closed circle and letting the head and tail drift around endlessly in that circle makes it unnecessary to ever move items stored in the array. If n is the size of the array, then computing indices modulo n will turn the array into a circle. This is still the conceptually simplest way to construct a queue in a high-level language, but it does admittedly slow things down a little, because the array indices must be compared to zero and the array size, which is comparable to the time taken to check whether an array index is out of bounds, which some languages do, but this will certainly be the method of choice for a quick and dirty implementation, or for any high-level language that does not have pointer syntax. The array size must be declared ahead of time, but some implementations simply double the declared array size when overflow occurs. Most modern languages with objects or pointers can implement or come with libraries for dynamic lists. Such data structures may have not specified a fixed capacity limit besides memory constraints. Queue overflow results from trying to add an element onto a full queue and queue underflow happens when trying to remove an element from an empty queue.

A bounded queue is a queue limited to a fixed number of items.[1]

There are several efficient implementations of FIFO queues. An efficient implementation is one that can perform the operations—en-queuing and de-queuing—in O(1) time.

- Linked list

- A doubly linked list has O(1) insertion and deletion at both ends, so it is a natural choice for queues.

- A regular singly linked list only has efficient insertion and deletion at one end. However, a small modification—keeping a pointer to the last node in addition to the first one—will enable it to implement an efficient queue.

- A deque implemented using a modified dynamic array

Queues and programming languages

Queues may be implemented as a separate data type, or maybe considered a special case of a double-ended queue (deque) and not implemented separately. For example, Perl and Ruby allow pushing and popping an array from both ends, so one can use push and shift functions to enqueue and dequeue a list (or, in reverse, one can use unshift and pop),[2] although in some cases these operations are not efficient.

C++'s Standard Template Library provides a "queue" templated class which is restricted to only push/pop operations. Since J2SE5.0, Java's library contains a Queue interface that specifies queue operations; implementing classes include LinkedList and (since J2SE 1.6) ArrayDeque. PHP has an SplQueue class and third party libraries like beanstalk'd and Gearman.

Example

A simple queue implemented in JavaScript:

class Queue {

constructor() {

this.items = [];

}

enqueue(element) {

this.items.push(element);

}

dequeue() {

return this.items.shift();

}

}

Purely functional implementation

Queues can also be implemented as a purely functional data structure.[3] There are two implementations. The first one only achieves per operation on average. That is, the amortized time is , but individual operations can take where n is the number of elements in the queue. The second implementation is called a real-time queue[4] and it allows the queue to be persistent with operations in O(1) worst-case time. It is a more complex implementation and requires lazy lists with memoization.

Amortized queue

This queue's data is stored in two singly-linked lists named and . The list holds the front part of the queue. The list holds the remaining elements (a.k.a., the rear of the queue) in reverse order. It is easy to insert into the front of the queue by adding a node at the head of . And, if is not empty, it is easy to remove from the end of the queue by removing the node at the head of . When is empty, the list is reversed and assigned to and then the head of is removed.

The insert ("enqueue") always takes time. The removal ("dequeue") takes when the list is not empty. When is empty, the reverse takes where is the number of elements in . But, we can say it is amortized time, because every element in had to be inserted and we can assign a constant cost for each element in the reverse to when it was inserted.

Real-time queue

The real-time queue achieves time for all operations, without amortization. This discussion will be technical, so recall that, for a list, denotes its length, that NIL represents an empty list and represents the list whose head is h and whose tail is t.

The data structure used to implement our queues consists of three singly-linked lists where f is the front of the queue and r is the rear of the queue in reverse order. The invariant of the structure is that s is the rear of f without its first elements, that is . The tail of the queue is then almost and inserting an element x to is almost . It is said almost, because in both of those results, . An auxiliary function must then be called for the invariant to be satisfied. Two cases must be considered, depending on whether is the empty list, in which case , or not. The formal definition is and where is f followed by r reversed.

Let us call the function which returns f followed by r reversed. Let us furthermore assume that , since it is the case when this function is called. More precisely, we define a lazy function which takes as input three lists such that , and return the concatenation of f, of r reversed and of a. Then . The inductive definition of rotate is and . Its running time is , but, since lazy evaluation is used, the computation is delayed until the results are forced by the computation.

The list s in the data structure has two purposes. This list serves as a counter for , indeed, if and only if s is the empty list. This counter allows us to ensure that the rear is never longer than the front list. Furthermore, using s, which is a tail of f, forces the computation of a part of the (lazy) list f during each tail and insert operation. Therefore, when , the list f is totally forced. If it was not the case, the internal representation of f could be some append of append of... of append, and forcing would not be a constant time operation anymore.

See also

- Circular buffer

- Double-ended queue (deque)

- Priority queue

- Queuing theory

- Stack (abstract data type) – the "opposite" of a queue: LIFO (Last In First Out)

References

- ↑ "Queue (Java Platform SE 7)". Docs.oracle.com. 2014-03-26. http://docs.oracle.com/javase/7/docs/api/java/util/Queue.html.

- ↑ "Array (Ruby 3.1)". 2021-12-25. https://ruby-doc.org/core-3.1.0/Array.html#class-Array-label-Adding+Items+to+Arrays.

- ↑ Okasaki, Chris. "Purely Functional Data Structures". https://doc.lagout.org/programmation/Functional%20Programming/Chris_Okasaki-Purely_Functional_Data_Structures-Cambridge_University_Press%281998%29.pdf.

- ↑ Hood, Robert; Melville, Robert (November 1981). "Real-time queue operations in pure Lisp". Information Processing Letters 13 (2): 50–54. doi:10.1016/0020-0190(81)90030-2.

General references

This article incorporates public domain material from the NIST document: Black, Paul E.. "Bounded queue". https://xlinux.nist.gov/dads/HTML/boundedqueue.html.

This article incorporates public domain material from the NIST document: Black, Paul E.. "Bounded queue". https://xlinux.nist.gov/dads/HTML/boundedqueue.html.

Further reading

- Donald Knuth. The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley, 1997. ISBN 0-201-89683-4. Section 2.2.1: Stacks, Queues, and Dequeues, pp. 238–243.

- Thomas H. Cormen, Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and Clifford Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, Second Edition. MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, 2001. ISBN 0-262-03293-7. Section 10.1: Stacks and queues, pp. 200–204.

- William Ford, William Topp. Data Structures with C++ and STL, Second Edition. Prentice Hall, 2002. ISBN 0-13-085850-1. Chapter 8: Queues and Priority Queues, pp. 386–390.

- Adam Drozdek. Data Structures and Algorithms in C++, Third Edition. Thomson Course Technology, 2005. ISBN 0-534-49182-0. Chapter 4: Stacks and Queues, pp. 137–169.

External links

|