Physics:Fermi liquid theory

| Condensed matter physics |

|---|

|

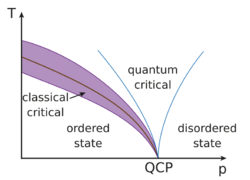

| Phases · Phase transition · QCP |

Fermi liquid theory (also known as Landau's Fermi-liquid theory) is a theoretical model of interacting fermions that describes the normal state of the conduction electrons in most metals at sufficiently low temperatures.[1] The theory describes the behavior of many-body systems of particles in which the interactions between particles may be strong. The phenomenological theory of Fermi liquids was introduced by the Soviet physicist Lev Davidovich Landau in 1956, and later developed by Alexei Abrikosov and Isaak Khalatnikov using diagrammatic perturbation theory.[2] The theory explains why some of the properties of an interacting fermion system are very similar to those of the ideal Fermi gas (collection of non-interacting fermions), and why other properties differ.

Fermi liquid theory applies most notably to conduction electrons in normal (non-superconducting) metals, and to liquid helium-3.[3] Liquid helium-3 is a Fermi liquid at low temperatures (but not low enough to be in its superfluid phase). An atom of helium-3 has two protons, one neutron and two electrons, giving an odd number of fermions, so the atom itself is a fermion. Fermi liquid theory also describes the low-temperature behavior of electrons in heavy fermion materials, which are metallic rare-earth alloys having partially filled f orbitals. The effective mass of electrons in these materials is much larger than the free-electron mass because of interactions with other electrons, so these systems are known as heavy Fermi liquids. Strontium ruthenate displays some key properties of Fermi liquids, despite being a strongly correlated material that is similar to high temperature superconductors such as the cuprates.[4] The low-momentum interactions of nucleons (protons and neutrons) in atomic nuclei are also described by Fermi liquid theory.[5]

Description

The key ideas behind Landau's theory are the notion of adiabaticity and the Pauli exclusion principle.[6] Consider a non-interacting fermion system (a Fermi gas), and suppose we "turn on" the interaction slowly. Landau argued that in this situation, the ground state of the Fermi gas would adiabatically transform into the ground state of the interacting system.

By Pauli's exclusion principle, the ground state [math]\displaystyle{ \Psi_0 }[/math] of a Fermi gas consists of fermions occupying all momentum states corresponding to momentum [math]\displaystyle{ p\lt p_{\rm F} }[/math] with all higher momentum states unoccupied. As the interaction is turned on, the spin, charge and momentum of the fermions corresponding to the occupied states remain unchanged, while their dynamical properties, such as their mass, magnetic moment etc. are renormalized to new values.[6] Thus, there is a one-to-one correspondence between the elementary excitations of a Fermi gas system and a Fermi liquid system. In the context of Fermi liquids, these excitations are called "quasiparticles".[1]

Landau quasiparticles are long-lived excitations with a lifetime [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math] that satisfies [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\hbar}{\tau}\ll\epsilon_{\rm p} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon_{\rm p} }[/math] is the quasiparticle energy (measured from the Fermi energy). At finite temperature, [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon_{\rm p} }[/math] is on the order of the thermal energy [math]\displaystyle{ k_{\rm B}T }[/math], and the condition for Landau quasiparticles can be reformulated as [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\hbar}{\tau}\ll k_{\rm B}T }[/math].

For this system, the many-body Green's function can be written[7] (near its poles) in the form

- [math]\displaystyle{ G(\omega,p)\approx\frac{Z}{\omega+\mu-\epsilon(p)} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math] is the chemical potential and [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon(p) }[/math] is the energy corresponding to the given momentum state.

The value [math]\displaystyle{ Z }[/math] is called the quasiparticle residue and is very characteristic of Fermi liquid theory. The spectral function for the system can be directly observed via angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES), and can be written (in the limit of low-lying excitations) in the form:

- [math]\displaystyle{ A(\mathbf{k},\omega)=Z\delta(\omega-v_{\rm F}k_{\|}) }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ v_{\rm F} }[/math] is the Fermi velocity.[8]

Physically, we can say that a propagating fermion interacts with its surrounding in such a way that the net effect of the interactions is to make the fermion behave as a "dressed" fermion, altering its effective mass and other dynamical properties. These "dressed" fermions are what we think of as "quasiparticles".[2]

Another important property of Fermi liquids is related to the scattering cross section for electrons. Suppose we have an electron with energy [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon_1 }[/math] above the Fermi surface, and suppose it scatters with a particle in the Fermi sea with energy [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon_2 }[/math]. By Pauli's exclusion principle, both the particles after scattering have to lie above the Fermi surface, with energies [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon_3,\epsilon_4\gt \epsilon_{\rm F} }[/math]. Now, suppose the initial electron has energy very close to the Fermi surface [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon\approx\epsilon_{\rm F} }[/math] Then, we have that [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon_2,\epsilon_3,\epsilon_4 }[/math] also have to be very close to the Fermi surface. This reduces the phase space volume of the possible states after scattering, and hence, by Fermi's golden rule, the scattering cross section goes to zero. Thus we can say that the lifetime of particles at the Fermi surface goes to infinity.[1]

Similarities to Fermi gas

The Fermi liquid is qualitatively analogous to the non-interacting Fermi gas, in the following sense: The system's dynamics and thermodynamics at low excitation energies and temperatures may be described by substituting the non-interacting fermions with interacting quasiparticles, each of which carries the same spin, charge and momentum as the original particles. Physically these may be thought of as being particles whose motion is disturbed by the surrounding particles and which themselves perturb the particles in their vicinity. Each many-particle excited state of the interacting system may be described by listing all occupied momentum states, just as in the non-interacting system. As a consequence, quantities such as the heat capacity of the Fermi liquid behave qualitatively in the same way as in the Fermi gas (e.g. the heat capacity rises linearly with temperature).

Differences from Fermi gas

The following differences to the non-interacting Fermi gas arise:

Energy

The energy of a many-particle state is not simply a sum of the single-particle energies of all occupied states. Instead, the change in energy for a given change [math]\displaystyle{ \delta n_k }[/math] in occupation of states [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] contains terms both linear and quadratic in [math]\displaystyle{ \delta n_k }[/math] (for the Fermi gas, it would only be linear, [math]\displaystyle{ \delta n_k \epsilon_k }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon_k }[/math] denotes the single-particle energies). The linear contribution corresponds to renormalized single-particle energies, which involve, e.g., a change in the effective mass of particles. The quadratic terms correspond to a sort of "mean-field" interaction between quasiparticles, which is parametrized by so-called Landau Fermi liquid parameters and determines the behaviour of density oscillations (and spin-density oscillations) in the Fermi liquid. Still, these mean-field interactions do not lead to a scattering of quasi-particles with a transfer of particles between different momentum states.

The renormalization of the mass of a fluid of interacting fermions can be calculated from first principles using many-body computational techniques. For the two-dimensional homogeneous electron gas, GW calculations[9] and quantum Monte Carlo methods[10][11][12] have been used to calculate renormalized quasiparticle effective masses.

Specific heat and compressibility

Specific heat, compressibility, spin-susceptibility and other quantities show the same qualitative behaviour (e.g. dependence on temperature) as in the Fermi gas, but the magnitude is (sometimes strongly) changed.

Interactions

In addition to the mean-field interactions, some weak interactions between quasiparticles remain, which lead to scattering of quasiparticles off each other. Therefore, quasiparticles acquire a finite lifetime. However, at low enough energies above the Fermi surface, this lifetime becomes very long, such that the product of excitation energy (expressed in frequency) and lifetime is much larger than one. In this sense, the quasiparticle energy is still well-defined (in the opposite limit, Heisenberg's uncertainty relation would prevent an accurate definition of the energy).

Structure

The structure of the "bare" particles (as opposed to quasiparticle) many-body Green's function is similar to that in the Fermi gas (where, for a given momentum, the Green's function in frequency space is a delta peak at the respective single-particle energy). The delta peak in the density-of-states is broadened (with a width given by the quasiparticle lifetime). In addition (and in contrast to the quasiparticle Green's function), its weight (integral over frequency) is suppressed by a quasiparticle weight factor [math]\displaystyle{ 0\lt Z\lt 1 }[/math]. The remainder of the total weight is in a broad "incoherent background", corresponding to the strong effects of interactions on the fermions at short time scales.

Distribution

The distribution of particles (as opposed to quasiparticles) over momentum states at zero temperature still shows a discontinuous jump at the Fermi surface (as in the Fermi gas), but it does not drop from 1 to 0: the step is only of size [math]\displaystyle{ Z }[/math].

Electrical resistivity

In a metal the resistivity at low temperatures is dominated by electron–electron scattering in combination with umklapp scattering. For a Fermi liquid, the resistivity from this mechanism varies as [math]\displaystyle{ T^2 }[/math], which is often taken as an experimental check for Fermi liquid behaviour (in addition to the linear temperature-dependence of the specific heat), although it only arises in combination with the lattice. In certain cases, umklapp scattering is not required. For example, the resistivity of compensated semimetals scales as [math]\displaystyle{ T^2 }[/math] because of mutual scattering of electron and hole. This is known as the Baber mechanism.[13]

Optical response

Fermi liquid theory predicts that the scattering rate, which governs the optical response of metals, not only depends quadratically on temperature (thus causing the [math]\displaystyle{ T^2 }[/math] dependence of the DC resistance), but it also depends quadratically on frequency.[14][15][16] This is in contrast to the Drude prediction for non-interacting metallic electrons, where the scattering rate is a constant as a function of frequency. One material in which optical Fermi liquid behavior was experimentally observed is the low-temperature metallic phase of Sr2RuO4.[17]

Instabilities

The experimental observation of exotic phases in strongly correlated systems has triggered an enormous effort from the theoretical community to try to understand their microscopic origin. One possible route to detect instabilities of a Fermi liquid is precisely the analysis done by Isaak Pomeranchuk.[18] Due to that, the Pomeranchuk instability has been studied by several authors [19] with different techniques in the last few years and in particular, the instability of the Fermi liquid towards the nematic phase was investigated for several models.

Non-Fermi liquids

The term non-Fermi liquid is used to describe a system which displays breakdown of Fermi-liquid behaviour. The simplest example is a system of interacting fermions in one dimension, called the Luttinger liquid.[3] Although Luttinger liquids are physically similar to Fermi liquids, the restriction to one dimension gives rise to several qualitative differences such as the absence of a quasiparticle peak in the momentum dependent spectral function, and the presence of spin-charge separation and of spin-density waves. One cannot ignore the existence of interactions in one dimension and has to describe the problem with a non-Fermi theory, where Luttinger liquid is one of them. At small finite spin temperatures in one dimension the ground state of the system is described by spin-incoherent Luttinger liquid (SILL).[20]

Another example of non-Fermi-liquid behaviour is observed at quantum critical points of certain second-order phase transitions, such as heavy fermion criticality, Mott criticality and high-[math]\displaystyle{ T_{\rm c} }[/math] cuprate phase transitions.[8] The ground state of such transitions is characterized by the presence of a sharp Fermi surface, although there may not be well-defined quasiparticles. That is, on approaching the critical point, it is observed that the quasiparticle residue [math]\displaystyle{ Z\to0 }[/math].

In optimally doped cuprates and iron-based superconductors, the normal state above the critical temperature shows signs of non-Fermi liquid behaviour, and is often called a strange metal. In this region of phase diagram, resistivity increases linearly in temperature and the Hall coefficient is found to depend on temperature.[21][22]

Understanding the behaviour of non-Fermi liquids is an important problem in condensed matter physics. Approaches towards explaining these phenomena include the treatment of marginal Fermi liquids; attempts to understand critical points and derive scaling relations; and descriptions using emergent gauge theories with techniques of holographic gauge/gravity duality.[23][24][25]

See also

- Classical fluid

- Fermionic condensate

- Luttinger liquid

- Luttinger's theorem

- Strongly correlated quantum spin liquid

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Phillips, Philip (2008). Advanced Solid State Physics. Perseus Books. pp. 224. ISBN 978-81-89938-16-1.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cross, Michael. "Fermi Liquid Theory: Principles". California Institute of Technology. http://www.pmaweb.caltech.edu/~mcc/Ph127/c/Lecture9.pdf.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Schulz, H. J. (March 1995). "Fermi liquids and non–Fermi liquids". In "proceedings of les Houches Summer School Lxi", ed. E. Akkermans, G. Montambaux, J. Pichard, et J. Zinn-Justin (Elsevier, Amsterdam 1995 (533). Bibcode: 1995cond.mat..3150S.

- ↑ Wysokiński, Carol (2003). "Spin triplet superconductivity in Sr2RuO4". Physica Status Solidi 236 (2): 325–331. doi:10.1002/pssb.200301672. Bibcode: 2003PSSBR.236..325W. http://www.phy.bris.ac.uk/people/annett_jf/papers/physicab.pdf. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ↑ Schwenk, Achim; Brown, Gerald E.; Friman, Bengt (2002). "Low-momentum nucleon–nucleon interaction and Fermi liquid theory". Nuclear Physics A 703 (3–4): 745–769. doi:10.1016/s0375-9474(01)01673-6. ISSN 0375-9474.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Coleman, Piers. Introduction to Many Body Physics. Rutgers University. pp. 143. http://www.physics.rutgers.edu/~coleman/620/mbody/pdf/bkx.pdf. Retrieved 2011-02-14. (draft copy)

- ↑ Lifshitz, E. M.; Pitaevskii, L.P. (1980). Statistical Physics (Part 2). Landau and Lifshitz. 9. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7506-2636-1.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Senthil, Todadri (2008). "Critical Fermi surfaces and non-Fermi liquid metals". Physical Review B 78 (3): 035103. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.78.035103. Bibcode: 2008PhRvB..78c5103S.

- ↑ R. Asgari; B. Tanatar (2006). "Many-body effective mass and spin susceptibility in a quasi-two-dimensional electron liquid". Physical Review B 74 (7): 075301. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.74.075301. Bibcode: 2006PhRvB..74g5301A. http://repository.bilkent.edu.tr/bitstream/11693/23741/1/bilkent-research-paper.pdf.

- ↑ Y. Kwon; D. M. Ceperley; R. M. Martin (2013). "Quantum Monte Carlo calculation of the Fermi-liquid parameters in the two-dimensional electron gas". Physical Review B 50 (3): 1684–1694. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.50.1684. PMID 9976356. Bibcode: 1994PhRvB..50.1684K.

- ↑ M. Holzmann; B. Bernu; V. Olevano; R. M. Martin; D. M. Ceperley (2009). "Renormalization factor and effective mass of the two-dimensional electron gas". Physical Review B 79 (4): 041308(R). doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.79.041308. Bibcode: 2009PhRvB..79d1308H.

- ↑ N. D. Drummond; R. J. Needs (2013). "Diffusion quantum Monte Carlo calculation of the quasiparticle effective mass of the two-dimensional homogeneous electron gas". Physical Review B 87 (4): 045131. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.87.045131. Bibcode: 2013PhRvB..87d5131D.

- ↑ Baber, W. G. (1937). "The Contribution to the Electrical Resistance of Metals from Collisions between Electrons". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 158 (894): 383–396. doi:10.1098/rspa.1937.0027. Bibcode: 1937RSPSA.158..383B.

- ↑ R. N. Gurzhi (1959). "MUTUAL ELECTRON CORRELATIONS IN METAL OPTICS". Sov. Phys. JETP 8: 673–675.

- ↑ M. Scheffler; K. Schlegel; C. Clauss; D. Hafner; C. Fella; M. Dressel; M. Jourdan; J. Sichelschmidt et al. (2013). "Microwave spectroscopy on heavy-fermion systems: Probing the dynamics of charges and magnetic moments". Phys. Status Solidi B 250 (3): 439–449. doi:10.1002/pssb.201200925. Bibcode: 2013PSSBR.250..439S.

- ↑ C. C. Homes; J. J. Tu; J. Li; G. D. Gu; A. Akrap (2013). "Optical conductivity of nodal metals". Scientific Reports 3 (3446): 3446. doi:10.1038/srep03446. PMID 24336241. Bibcode: 2013NatSR...3E3446H.

- ↑ D. Stricker; J. Mravlje; C. Berthod; R. Fittipaldi; A. Vecchione; A. Georges; D. van der Marel (2014). "Optical Response of Sr2RuO4 Reveals Universal Fermi-Liquid Scaling and Quasiparticles Beyond Landau Theory". Physical Review Letters 113 (8): 087404. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.087404. PMID 25192127. Bibcode: 2014PhRvL.113h7404S.

- ↑ I. I. Pomeranchuk (1959). "ON THE STABILITY OF A FERMI LIQUID". Sov. Phys. JETP 8: 361–362.

- ↑ Actually, this is a subject of investigation, see for example: https://arxiv.org/abs/0804.4422.

- ↑ M. Soltanieh-ha, A. E. Feiguin (2012). "Class of variational Ansätze for the spin-incoherent ground state of a Luttinger liquid coupled to a spin bath". Physical Review B 86 (20): 205120. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.86.205120. Bibcode: 2012PhRvB..86t5120S.

- ↑ Lee, Patrick A.; Nagaosa, Naoto; Wen, Xiao-Gang (2006-01-06). "Doping a Mott insulator: Physics of high-temperature superconductivity" (in en). Reviews of Modern Physics 78 (1): 17–85. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.78.17. ISSN 0034-6861. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/RevModPhys.78.17.

- ↑ Varma, Chandra M. (2020-07-07). "Colloquium : Linear in temperature resistivity and associated mysteries including high temperature superconductivity" (in en). Reviews of Modern Physics 92 (3). doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.92.031001. ISSN 0034-6861. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/RevModPhys.92.031001.

- ↑ Faulkner, Thomas; Polchinski, Joseph (2010). "Semi-Holographic Fermi Liquids". Journal of High Energy Physics 2011 (6): 12. doi:10.1007/JHEP06(2011)012. Bibcode: 2011JHEP...06..012F.

- ↑ Guo, Haoyu; Gu, Yingfei; Sachdev, Subir (2020). "Linear in temperature resistivity in the limit of zero temperature from the time reparameterization soft mode". Annals of Physics 418: 168202. doi:10.1016/j.aop.2020.168202.

- ↑ Wei, Chenan; Sedrakyan, Tigran A. (2023-08-02). "Strange metal phase of disordered magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene at low temperatures: From flat bands to weakly coupled Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev bundles". Physical Review B 108 (6). doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.108.064202. ISSN 2469-9950.

|