Chemistry:Acesulfame potassium

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

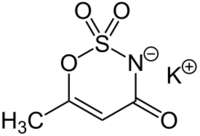

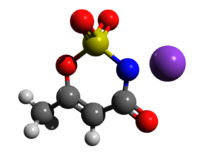

| IUPAC name

Potassium 6-methyl-2,2-dioxo-2H-1,2λ6,3-oxathiazin-4-olate

| |

| Other names

Acesulfame K; Ace K

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C4H4KNO4S | |

| Molar mass | 201.242 |

| Appearance | white crystalline powder |

| Density | 1.81 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 225 °C (437 °F; 498 K) |

| 270 g/L at 20 °C | |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Acesulfame potassium (UK: /æsɪˈsʌlfeɪm/,[1] US: /ˌeɪsiːˈsʌlfeɪm/ AY-see-SUL-faym[2] or /ˌæsəˈsʌlfeɪm/[1]), also known as acesulfame K (K is the symbol for potassium) or Ace K, is a synthetic calorie-free sugar substitute (artificial sweetener) often marketed under the trade names Sunett and Sweet One. In the European Union, it is known under the E number (additive code) E950.[3] It was discovered accidentally in 1967 by German chemist Karl Clauss at Hoechst AG (now Nutrinova).[4] In chemical structure, acesulfame potassium is the potassium salt of 6-methyl-1,2,3-oxathiazine-4(3H)-one 2,2-dioxide. It is a white crystalline powder with molecular formula C4H4KNO4S and a molecular weight of 201.24 g/mol.[5]

Properties

Acesulfame K is 200 times sweeter than sucrose (common sugar), as sweet as aspartame, about two-thirds as sweet as saccharin, and one-third as sweet as sucralose. Like saccharin, it has a slightly bitter aftertaste, especially at high concentrations. Kraft Foods patented the use of sodium ferulate to mask acesulfame's aftertaste.[6] Acesulfame K is often blended with other sweeteners (usually sucralose or aspartame). These blends are reputed to give a more sucrose-like taste whereby each sweetener masks the other's aftertaste, or exhibits a synergistic effect by which the blend is sweeter than its components.[7] Acesulfame potassium has a smaller particle size than sucrose, allowing for its mixtures with other sweeteners to be more uniform.[8]

Unlike aspartame, acesulfame K is stable under heat, even under moderately acidic or basic conditions, allowing it to be used as a food additive in baking, or in products that require a long shelf life. Although acesulfame potassium has a stable shelf life, it can eventually degrade to acetoacetamide, which is toxic in high doses.[9] In carbonated drinks, it is almost always used in conjunction with another sweetener, such as aspartame or sucralose. It is also used as a sweetener in protein shakes and pharmaceutical products,[10] especially chewable and liquid medications, where it can make the active ingredients more palatable. The acceptable daily intake of acesulfame potassium is listed as 15 mg/kg/day.[11]

Acesulfame potassium is widely used in the human diet and excreted by the kidneys. It thus has been used by researchers as a marker to estimate to what degree swimming pools are contaminated by urine.[12]

Other names for acesulfame K are potassium acesulfamate, potassium salt of 6-methyl-1,2,3-oxothiazin-4(3H)-one-2,3-dioxide, and potassium 6-methyl-1,2,3-oxathiazine-4(3H)-one-3-ate-2,2-dioxide.

Effect on body weight

Acesulfame potassium provides a sweet taste with no caloric value. There is no high-quality evidence that using acesulfame potassium as a sweetener affects body weight or body mass index (BMI).[13][14][15]

Discovery

Acesulfame potassium was developed after the accidental discovery of a similar compound (5,6-dimethyl-1,2,3-oxathiazin-4(3H)-one 2,2-dioxide) in 1967 by Karl Clauss and Harald Jensen at Hoechst AG.[16][17] After accidentally dipping his fingers into the chemicals with which he was working, Clauss licked them to pick up a piece of paper.[18] Clauss is the inventor listed on a United States patent issued in 1975 to the assignee Hoechst Aktiengesellschaft for one process of manufacturing acesulfame potassium.[19] Subsequent research showed a number of compounds with the same basic ring structure had varying levels of sweetness. 6-methyl-1,2,3-oxathiazine-4(3H)-one 2,2-dioxide had particularly favourable taste characteristics and was relatively easy to synthesize, so it was singled out for further research, and received its generic name (acesulfame-K) from the World Health Organization in 1978.[16] Acesulfame potassium first received approval for table top use in the United States in 1988.[11]

Safety

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved its general use as a safe food additive in 1988,[20] and maintains that safety assessment, as of 2023.[21] In a 2000 scientific review, the European Food Safety Authority determined that acesulfame K is safe in typical consumption amounts, and does not increase the risk of diseases.[22]

Environment Canada tested the water from the Grand River at 23 sites between its headwaters and where it flows into Lake Erie. The results suggest that acesulfame appears in far higher concentrations than saccharin or sucralose at the various test sites.[23]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "acesulfame". Oxford English Dictionary. OED. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/247745. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ↑ "acesulfame–K". https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/acesulfame%E2%80%93K.

- ↑ "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". UK: Food Standards Agency. 2012-03-14. http://www.food.gov.uk/policy-advice/additivesbranch/enumberlist.

- ↑ Clauss, K.; Jensen, H. (1973). "Oxathiazinone Dioxides - A New Group of Sweetening Agents". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 12 (11): 869–876. doi:10.1002/anie.197308691.

- ↑ Ager, D. J.; Pantaleone, D. P.; Henderson, S. A.; Katritzky, A. R.; Prakash, I.; Walters, D. E. (1998). "Commercial, Synthetic Nonnutritive Sweeteners". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 37 (13–14): 1802–1817. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980803)37:13/14<1802::AID-ANIE1802>3.0.CO;2-9. http://ufark12.chem.ufl.edu/Published_Papers/PDF/728.pdf.

- ↑ United States Patent 5,336,513 (expired in 2006)

- ↑ "Customizing Sweetness Profiles". Food Product Design. November 2006. http://nfscfaculty.tamu.edu/talcott/courses/FSTC605/Food%20Product%20Design/Customizing%20Sweetness.pdf.

- ↑ Mullarney, M.; Hancock, B.; Carlson, G.; Ladipo, D.; Langdon, B. "The powder flow and compact mechanical properties of sucrose and three high-intensity sweeteners used in chewable tablets". Int. J. Pharm. 2003, 257, 227–236.

- ↑ Findikli, Z.; Zeynep, F.; Sifa, T. Determination of the effects of some artificial sweeteners on human peripheral lymphocytes using the comet assay. Journal of toxicology and environmental health sciences 2014, 6, 147–153.

- ↑ "Home – WHO – Prequalification of Medicines Programme". https://www.who.int/prequal/trainingresources/pq_pres/TrainingZA-April07/Excipients.ppt.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Whitehouse, C.; Boullata, J.; McCauley, L. "The potential toxicity of artificial sweeteners". AAOHN J. 2008, 56, 251–259, quiz 260.

- ↑ Erika Engelhaupt (March 1, 2017). "Just How Much Pee Is In That Pool?". NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/03/01/517785902/just-how-much-pee-is-in-that-pool.

- ↑ "Low-calorie sweeteners and body weight and composition: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 100 (3): 765–777. September 2014. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.082826. PMID 24944060.

- ↑ "Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies". CMAJ 189 (28): E929–E939. July 2017. doi:10.1503/cmaj.161390. PMID 28716847.

- ↑ "Does low-energy sweetener consumption affect energy intake and body weight? A systematic review, including meta-analyses, of the evidence from human and animal studies". International Journal of Obesity 40 (3): 381–94. September 2015. doi:10.1038/ijo.2015.177. PMID 26365102.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 O'Brien-Nabors, L. (2001). Alternative Sweeteners. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8247-0437-7.

- ↑ Williams, R. J.; Goldberg, I. (1991). Biotechnology and Food Ingredients. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. ISBN 978-0-442-00272-5.

- ↑ Newton, D. E. (2007). Food Chemistry (New Chemistry). New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-8160-5277-6. https://www.scribd.com/doc/50359642/Food-Chemistry#page=82. Retrieved 2017-09-08.

- ↑ Clauss, K., "Process for the manufacture of 6-methyl-3,4-dihydro-1,2,3-oxathiazine-4-one-2,2-dioxide", US patent 3917589, issued 1975

- ↑ Kroger, M.; Meister, K.; Kava, R. (2006). "Low-Calorie Sweeteners and Other Sugar Substitutes: A Review of the Safety Issues". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 5 (2): 35–47. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2006.tb00081.x.

- ↑ "Aspartame and Other Sweeteners in Food". US Food and Drug Administration. 30 May 2023. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-additives-petitions/aspartame-and-other-sweeteners-food.

- ↑ Scientific Committee on Food (2000). "Opinion - Re-evaluation of acesulfame K with reference to the previous SCF opinion of 1991". SCF/CS/ADD/EDUL/194 final. EU Commission. http://ec.europa.eu/food/fs/sc/scf/out52_en.pdf.

- ↑ "Major Canadian river contains artificial sweeteners". Waterloo News (University of Waterloo). December 13, 2013. https://uwaterloo.ca/news/news/major-canadian-river-contains-artificial-sweeteners.

External links

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives evaluation monograph of Acesulfame Potassium

- FDA approval of Acesulfame Potassium

- FDA approval of Acesulfame Potassium as a General Purpose Sweetener in Food

- Elmhurst College, Illinois Virtual ChemBook Acesulfame K

- Discovery News Sweeteners Linger in Groundwater

|