Undersampling

In signal processing, undersampling or bandpass sampling is a technique where one samples a bandpass-filtered signal at a sample rate below its Nyquist rate (twice the upper cutoff frequency), but is still able to reconstruct the signal.

When one undersamples a bandpass signal, the samples are indistinguishable from the samples of a low-frequency alias of the high-frequency signal. Such sampling is also known as bandpass sampling, harmonic sampling, IF sampling, and direct IF-to-digital conversion.[1]

Description

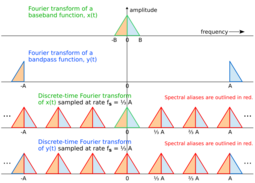

The Fourier transforms of real-valued functions are symmetrical around the 0 Hz axis. After sampling, only a periodic summation of the Fourier transform (called discrete-time Fourier transform) is still available. The individual frequency-shifted copies of the original transform are called aliases. The frequency offset between adjacent aliases is the sampling-rate, denoted by fs. When the aliases are mutually exclusive (spectrally), the original transform and the original continuous function, or a frequency-shifted version of it (if desired), can be recovered from the samples. The first and third graphs of Figure 1 depict a baseband spectrum before and after being sampled at a rate that completely separates the aliases.

The second graph of Figure 1 depicts the frequency profile of a bandpass function occupying the band (A, A+B) (shaded blue) and its mirror image (shaded beige). The condition for a non-destructive sample rate is that the aliases of both bands do not overlap when shifted by all integer multiples of fs. The fourth graph depicts the spectral result of sampling at the same rate as the baseband function. The rate was chosen by finding the lowest rate that is an integer sub-multiple of A and also satisfies the baseband Nyquist criterion: fs > 2B. Consequently, the bandpass function has effectively been converted to baseband. All the other rates that avoid overlap are given by these more general criteria, where A and A+B are replaced by fL and fH, respectively:[2][3]

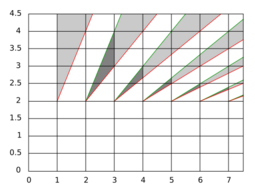

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{2 f_H}{n} \le f_s \le \frac{2 f_L}{n - 1} }[/math], for any integer n satisfying: [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \le n \le \left\lfloor \frac{f_H}{f_H-f_L} \right\rfloor }[/math]

The highest n for which the condition is satisfied leads to the lowest possible sampling rates.

Important signals of this sort include a radio's intermediate-frequency (IF), radio-frequency (RF) signal, and the individual channels of a filter bank.

If n > 1, then the conditions result in what is sometimes referred to as undersampling, bandpass sampling, or using a sampling rate less than the Nyquist rate (2fH). For the case of a given sampling frequency, simpler formulae for the constraints on the signal's spectral band are given below.

- Example: Consider FM radio to illustrate the idea of undersampling.

- In the US, FM radio operates on the frequency band from fL = 88 MHz to fH = 108 MHz. The bandwidth is given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ W = f_H - f_L = 108 \ \mathrm{MHz} - 88 \ \mathrm{MHz} = 20 \ \mathrm{MHz} }[/math]

- The sampling conditions are satisfied for

- [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \le n \le \lfloor 5.4 \rfloor = \left\lfloor { 108 \ \mathrm{MHz} \over 20 \ \mathrm{MHz} } \right\rfloor }[/math]

- Therefore, n can be 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5.

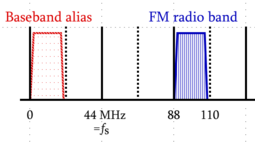

- The value n = 5 gives the lowest sampling frequencies interval [math]\displaystyle{ 43.2\ \mathrm{MHz}\lt f_\mathrm{s}\lt 44\ \mathrm{MHz} }[/math] and this is a scenario of undersampling. In this case, the signal spectrum fits between 2 and 2.5 times the sampling rate (higher than 86.4–88 MHz but lower than 108–110 MHz).

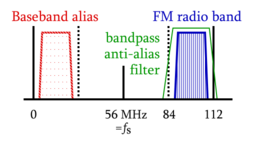

- A lower value of n will also lead to a useful sampling rate. For example, using n = 4, the FM band spectrum fits easily between 1.5 and 2.0 times the sampling rate, for a sampling rate near 56 MHz (multiples of the Nyquist frequency being 28, 56, 84, 112, etc.). See the illustrations at the right.

- When undersampling a real-world signal, the sampling circuit must be fast enough to capture the highest signal frequency of interest. Theoretically, each sample should be taken during an infinitesimally short interval, but this is not practically feasible. Instead, the sampling of the signal should be made in a short enough interval that it can represent the instantaneous value of the signal with the highest frequency. This means that in the FM radio example above, the sampling circuit must be able to capture a signal with a frequency of 108 MHz, not 43.2 MHz. Thus, the sampling frequency may be only a little bit greater than 43.2 MHz, but the input bandwidth of the system must be at least 108 MHz. Similarly, the accuracy of the sampling timing, or aperture uncertainty of the sampler, frequently the analog-to-digital converter, must be appropriate for the frequencies being sampled 108MHz, not the lower sample rate.

- If the sampling theorem is interpreted as requiring twice the highest frequency, then the required sampling rate would be assumed to be greater than the Nyquist rate 216 MHz. While this does satisfy the last condition on the sampling rate, it is grossly oversampled.

- Note that if a band is sampled with n > 1, then a band-pass filter is required for the anti-aliasing filter, instead of a lowpass filter.

As we have seen, the normal baseband condition for reversible sampling is that X(f) = 0 outside the interval: [math]\displaystyle{ \scriptstyle \left(-\frac12f_\mathrm{s},\frac12f_\mathrm{s}\right), }[/math]

and the reconstructive interpolation function, or lowpass filter impulse response, is [math]\displaystyle{ \scriptstyle \operatorname{sinc} \left(t/T\right). }[/math]

To accommodate undersampling, the bandpass condition is that X(f) = 0 outside the union of open positive and negative frequency bands

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left(-\frac{n}2f_\mathrm{s},-\frac{n-1}2f_\mathrm{s}\right) \cup\left(\frac{n-1}2f_\mathrm{s},\frac{n}2f_\mathrm{s}\right) }[/math] for some positive integer [math]\displaystyle{ n\, }[/math].

- which includes the normal baseband condition as case n = 1 (except that where the intervals come together at 0 frequency, they can be closed).

The corresponding interpolation function is the bandpass filter given by this difference of lowpass impulse responses:

- [math]\displaystyle{ n\operatorname{sinc} \left(\frac{nt}T\right) - (n-1)\operatorname{sinc} \left( \frac{(n-1)t}T \right) }[/math].

On the other hand, reconstruction is not usually the goal with sampled IF or RF signals. Rather, the sample sequence can be treated as ordinary samples of the signal frequency-shifted to near baseband, and digital demodulation can proceed on that basis, recognizing the spectrum mirroring when n is even.

Further generalizations of undersampling for the case of signals with multiple bands are possible, and signals over multidimensional domains (space or space-time) and have been worked out in detail by Igor Kluvánek.

See also

References

- ↑ Walt Kester (2003). Mixed-signal and DSP design techniques. Newnes. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7506-7611-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=G8XyNItpy8AC&pg=PA20.

- ↑ Hiroshi Harada, Ramjee Prasad (2002). Simulation and Software Radio for Mobile Communications. Artech House. ISBN 1-58053-044-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=amhNM01OKCUC&dq=nyquist+sampling+rf+if&pg=PA395.

- ↑ Angelo Ricotta. "Undersampling SODAR Signals". http://spazioscuola.altervista.org/UndersamplingAR/UndersamplingARnv.htm.

|