Biography:Albert Luthuli

Inkosi Albert Luthuli | |

|---|---|

| |

| President-General of the African National Congress | |

| In office December 1952 – 21 July 1967 | |

| Preceded by | James Moroka |

| Succeeded by | Oliver Tambo |

| Rector of the University of Glasgow | |

| In office 1962–1965 | |

| Preceded by | Quintin Hogg |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Reith |

| Chief of the Umvoti River Reserve | |

| In office January 1936 – November 1952 | |

| Preceded by | Martin Luthuli |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1898 Bulawayo, Rhodesia |

| Died | (aged c. 69) Stanger, Natal, South Africa |

| Resting place | Groutville Congregationalist Church, Stanger |

| Nationality | South African |

| Political party | African National Congress |

| Other political affiliations | Congress Alliance |

| Spouse(s) | Nokukhanya Bhengu (m. 1927) |

| Children | 7, including Albertina |

| Alma mater | Adams College |

| Occupation |

|

| Awards |

|

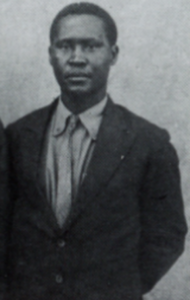

Albert John Luthuli[lower-alpha 1] (c. 1898 – 21 July 1967) was a South African anti-apartheid activist, traditional leader, and politician who served as the President-General of the African National Congress from 1952 until his death in 1967.

Luthuli was born to a Zulu family in 1898 at a Seventh-day Adventist mission in Bulawayo, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). In 1908 he moved to Groutville, where his parents and grandparents had lived, to attend school under the care of his uncle. After graduating from high school with a teaching degree, Luthuli became principal of a small school in Natal where he was the sole teacher. He accepted a government bursary to study for the Higher Teacher's Diploma at Adams College. After the completion of his studies in 1922, he accepted a teaching position at Adams College where he was one of the first African teachers. In 1928, he became the secretary of the Natal Native Teachers' Association, then its president in 1933.

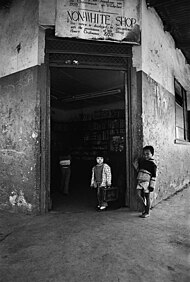

Luthuli's entered South African politics and the anti-apartheid movement in 1935, when he was elected chief of the Umvoti River Reserve in Groutville. As chief, he was exposed to the injustices facing many Africans due to the South African government's increasingly segregationist policies. This segregation would later evolve into apartheid, a form of institutionalized racial segregation, following the National Party's election victory in 1948. Luthuli joined the African National Congress (ANC) in 1944 and was elected the provincial president of the Natal branch in 1951. A year later in 1952, Luthuli led the Defiance Campaign to protest the pass laws and other laws of apartheid. As a result, the government removed him from his chief position as he refused to choose between being a member of the ANC or a chief at Groutville. In the same year, he was elected President-General of the ANC. After the Sharpeville massacre, where sixty-nine Africans were killed, leaders within the ANC such as Nelson Mandela believed the organisation should take up armed resistance against the government. Luthuli was initially against the use of violence. He later gradually came to accept it, but stayed committed to nonviolence on a personal level. Following four banning orders, the imprisonment and exile of his political allies, and the banning of the ANC, Luthuli's power as President-General gradually waned. The subsequent creation of uMkhonto we Sizwe, the ANC's paramilitary wing, marked the anti-apartheid movement's shift from nonviolence to an armed struggle.

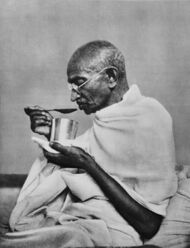

Inspired by his Christian faith and the nonviolent methods used by Gandhi, Luthuli was praised for his dedication to nonviolent resistance against apartheid as well as his vision of a non-racial South African society. In 1961, Luthuli was awarded the 1960 Nobel Peace Prize for his role in leading the nonviolent anti-apartheid movement. Luthuli's supporters brand him as a global icon of peace similar to Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr, the latter of whom was a follower and admirer of Luthuli. He formed multi-racial alliances with the South African Indian Congress and the white Congress of Democrats, frequently drawing a backlash from Africanists in the ANC. The Africanist bloc believed that Africans should not ally themselves with other races, since Africans were the most disadvantaged race under apartheid. This schism led to the creation of the Pan-Africanist Congress.

Early life

Albert John Luthuli was born at the Solusi Mission Station, a Seventh-day Adventist missionary station, in 1898[lower-alpha 2][3] to John and Mtonya Luthuli (née Gumede) who had settled in the Bulawayo area of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).[4] He was the youngest of three children[5] and had two brothers, Mpangwa, who died at birth, and Alfred Nsusana.[3] Luthuli's father died when he was about six months old, and Luthuli had no recollection of him. His father's death led to him being mainly raised by his mother Mtonya, who had spent her childhood in the royal household of King Cetshwayo in Zululand.[6]

Mtonya had converted to Christianity and lived with the American Board Mission prior to her marriage to John Luthuli. During her stay, she learned how to read and became a dedicated reader of the Bible until her death. Despite being able to read, Mtonya never learned how to write. After their marriage, Luthuli's father left Natal and went to Rhodesia during the Second Matabele War to serve with the Rhodesian forces.[2] When the war ended, John stayed in Rhodesia with a Seventh-day Adventist mission near Bulawayo and worked as an interpreter and evangelist. Mtonya and Alfred then travelled to Rhodesia to reunite with John, and Luthuli was born there soon after.[2]

Luthuli's paternal grandparents, Ntaba ka Madunjini and Titsi Mthethwa, were born in the early nineteenth century and had fought against potential annexation from Shaka's Zulu Kingdom.[7] They were also among the first converts of Aldin Grout, a missionary from the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABM), which was based near the Umvoti River north of Durban.[8] The abasemakholweni, a converted Christian community within the Umvoti Mission Station, elected Ntaba as their chief in 1860. This marked the start of a family tradition, as Ntaba's brother, son Martin, and grandson Albert were also subsequently elected as chiefs.[7]

Youth

Around 1908 or 1909, the Seventh-day Adventists expressed their interest in beginning missionary work in Natal and requested the services of Luthuli's brother, Alfred, to work as an interpreter. Luthuli and his mother followed, and departed Rhodesia to return to South Africa. Luthuli's family settled in the Vryheid district of Northern Natal, and resided on the farm of a Seventh-day Adventist. During this time, Luthuli was responsible for tending to the missionary's mules as educational opportunities were not available. Luthuli's mother recognised his need for a formal education and sent him to live in Groutville under the care of his uncle.[9] Groutville was a small village inhabited predominantly by poor Christian farmers who were affiliated with the nearby mission station run by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABM). The ABM, which commenced operations in Southern Africa in 1834, was a Congregationalist organisation responsible for setting up the Umvoti Mission Station. After the death of ABM missionary Aldin Grout in 1894, the town surrounding the mission station was renamed Groutville.[7]

Luthuli resided in the home of his uncle, Chief Martin Luthuli, and his family. Martin was the first democratically elected chief of Groutville. In 1901, Martin founded the Natal Native Congress, which would later become the Natal branch of the African National Congress.[10][11] Luthuli had a pleasant childhood as his uncle Martin was guardian over many children in Groutville, which led to Luthuli having many friends of his own age.[12] In Martin's traditional Zulu household, Luthuli completed chores expected of a Zulu boy his age such as fetching water, herding, and building fires.[11] Additionally, he attended school for the first time.[12] Under Martin's care, Luthuli was also provided with an early knowledge of traditional African politics and affairs, which aided him in his future career as a traditional chief.[13]

Education

Luthuli's mother, Mtonya, returned to Groutville and Luthuli returned to her care. They lived in a brand-new house built by his brother, Alfred, on the site where their grandfather, Ntaba, had once lived.[14] In order to be able to send her son to boarding school, Mtonya worked long hours in the fields of the land she owned. She also took in laundry from European families in the township of Stanger[12] to earn the necessary money for school.[15] Luthuli was educated at a local ABM mission school until 1914, and then transferred to the Ohlange Institute.[15]

Ohlange was founded by John Dube, who was the school principal at the time Luthuli attended.[16] Dube was educated in America but returned to South Africa to open the Ohlange Institute to provide an education to black children. He was the first President-General of the South African Native National Congress and founded the first Zulu-language newspaper, Ilanga lase Natal.[15] Luthuli joined the ANC in 1944, partially out of respect to his former school principal.[17]

Luthuli describes his experience at the Ohlange Institute as "rough-and-tumble."[16] The outbreak of World War I led to rationing and a scarcity of food among the African population. After attending Ohlange for only two terms, Luthuli was transferred to Edendale, a Methodist school near Pietermaritzburg, the capital of Natal.[16] It was at Edendale that Luthuli participated in his first act of civil disobedience.[18] He joined a protest against a punishment which made boys carry large stones long distances, damaging their uniforms, and leaving many unable to afford replacements.[19][15] The demonstration failed and Luthuli along with the rest of the strikers were punished by the school.[20] At Edendale, Luthuli developed a passion for teaching and went on to graduate with a teaching degree in 1917.[15][18]

Teaching

Around the age of nineteen years old, Luthuli's first job after graduation came as a principal at a rural intermediate school in Blaauwbosch, located in the Natal midlands. The school was small, and Luthuli was the sole teacher working there.[15] While teaching at Blaauwbosch, Luthuli lived with a Methodist's family. As there were no Congregational churches around him, he became the student of a local Methodist minister, the Reverend Mthembu. He was confirmed in the Methodist church and later became a lay preacher.[21][22]

Luthuli proved himself to be a good teacher and the Natal Department of Education offered him a bursary in 1920 to study for a Higher Teacher's Diploma at Adams College.[23] Following the completion of his two years of study, he was offered another bursary, this time to study at the University of Fort Hare in the Eastern Cape. He refused, as he wanted to earn a salary to take care of his ageing mother.[22] This led him to accept a teaching position at Adams College, where he and Z. K. Matthews were among the first African teachers at the school.[24] Luthuli taught Zulu history, music, and literature,[24][22] and during his time as a teacher, he met his future wife, Nokukhanya Bhengu.[25] She was also a teacher at Adams and the granddaughter of a Zulu chief.[25][26] Luthuli was committed to providing quality education to African children and led the Teachers' College at Adams where he trained aspiring teachers and travelled to different institutions to teach students.[24]

Early political activity

Natal Native Teachers' Association

Luthuli was elected as the secretary of the Natal Native Teachers' Association in 1928 and served under Z. K. Matthews' presidency. He became the president of the association in 1933.[27] The association had three goals: improving working conditions for African teachers, motivating members to expand their skills, and encouraging members to participate in leisure activities such as sports, music and social gatherings.[28] Despite making little progress in achieving its stated goals, the association is remembered for its opposition to the Chief Inspector for Native Education in Natal, Charles Loram, and his proposal that Africans be educated in "practical functions" and left to "develop along their own lines". Loram's position would serve as the ideological basis for the National Party's Bantu Education policy.[29]

The Zulu Language and Cultural Society

After becoming disappointed with the Natal Native Teachers' Association's slow progress, Luthuli shifted his attention to establishing a new branch of the Teachers' Association called the Zulu Language and Cultural Society in 1935. Dinizulu, the Zulu king, served as one of the society's patrons, and John Dube served as its inaugural president. Luthuli described the purpose of the society as the preservation of what is valuable to Zulu culture while removing the inappropriate practices and beliefs. Luthuli's involvement with the society was brief, as he assumed the role of chief in Groutville and could not remain actively involved. As a result, the society's goals changed from its original purpose.[30] According to historian Shula Marks, the primary goal of the Zulu Language and Cultural Society was to secure government recognition of the Zulu royal family as the official leaders of the Zulu people. The preservation of Zulu tradition and custom was a secondary goal.[31] Grants and gifts from the South African Native Affairs Department as well as the society's involvement with the Zulu royal house led to its demise as it collapsed in 1946. Seeing no real progress being made by the Teachers' Association and Zulu Society, Luthuli felt compelled to reject the government as a potential collaborator.[32]

Cane Growers' Association

The 1936 Sugar Act limited production of sugar in order to keep the price from falling.[33] A quota system was implemented, and, for African cane growers, it was severely limiting. As a response Luthuli decided to revive the Groutville Cane Growers' Association of which he became chairman.[34] The association was used to make collective bargaining and advocacy more effective. The association achieved a significant victory: an amendment was made to the Sugar Act that allowed African cane growers to have a comprehensive quota. This meant if some farmers were unable to meet their individual quotas, others could make up the difference, ensuring that all cane would be sold and not wasted in the farms.[34][35]

Luthuli then founded the Natal and Zululand Bantu Cane Growers' Association, which he served as chairman.[36] The association brought almost all African cane growers into a single union.[17] It had very few achievements, but one of them was securing indirect representation on the central board through a non-white advisory board that was concerned with the production, processing, and marketing of sugar.[37] The structural inequalities and discrimination present in South African society hindered the association's efforts to promote the interests of non-white canegrowers, and they proved to be little match for the white canegrowers' associations.[38] As with the Teachers' Association, Luthuli was disappointed with the Growers' Association's few successes. He believed that whatever political role he took part in, the stubbornness and hostility of the government would prevent any significant progress from being made.[38] Luthuli continued to support the interests of black cane growers, and was the only black representative on the central board until 1953.[38]

Chief of Groutville

In 1933, Luthuli was asked to succeed his uncle, Martin, as chief of the Umvoti River Reserve.[39] He took two years to make his decision. His salary as a teacher was enough for him to send money home to support his family, but if he accepted the chieftainship he would earn less than one-fifth of his current salary.[40] Furthermore, leaving a job at Adams College, where he worked with people of different ethnicities from all over South Africa, to become a Zulu chief appeared to be a move towards a more insular way of life.[41] Luthuli opted for the role of chief and said he was not motivated by a desire for wealth, fame, or power.[42] At the end of 1935, he was elected as chief and relocated to Groutville.[42] He commenced his duties on January 1936[43][44] and continued in the role until he was deposed by the South African government in 1952.[45][46]

Some chiefs abused their power and used their close relationship with the government to act as dictators. They increased their wealth by claiming ownership of land that was not rightfully theirs, charged excessive fees for services, and accepted bribes to resolve disputes.[47] Despite his reduced salary as a chief, Luthuli rejected corrupt practices. He embraced the concept of Ubuntu, which emphasized the humanity of all people, and governed with an inclusive and democratic approach. He believed that traditional Zulu governance was inherently democratic, with chiefs obligated to respond to the needs of their people.[43] Luthuli was seen as a chief of his people: one community member remembered Luthuli as a "man of the people who had a very strong influence over the community. He was a people's chief."[48] Luthuli involved women, who were considered socially inferior, in the decision-making process of his leadership. He also improved their economic status by allowing them to engage in activities such as beer brewing and running unlicensed bars, despite a government prohibition on these practices.[48]

The position of Africans in the reserves continued to regress as a result of laws passed that controlled their social mobility.[49] The Hertzog Bills were introduced a year after Luthuli was elected chief and were instrumental in the restriction and control of Africans. The first bill, the Natives Representation Bill, removed Africans from the voters' roll in the Cape and created the Natives Representative Council (NRC).[50] The second bill, the Natives Land and Trust Bill, restricted the land available to the African population of 12 million to less than 13 per cent. The remaining 87 per cent of land in South Africa was primarily reserved for the white population of approximately 3 million in 1936.[51][42] Limited access to land and poor agricultural technology negatively affected the people of Groutville, and the government's policies led to a shortage of land, education, and job opportunities, which limited the potential achievements of the population.[35] Luthuli viewed the conditions of Groutville as a microcosm that affected all black people in South Africa.[35]

Natives Representative Council

— Albert Luthuli's response to claims that the Native Representative Council was ineffective.[52]

The Natives Representative Council (NRC), an advisory body to the government, was established in 1936 with the purpose of compensating and appeasing the African population, who had lost their limited voting rights in the Cape Province due to the enactment of the Hertzog Bills.[50][53][54]

In 1946, after John Dube's death, Luthuli became a member of the Natives Representative Council through a by-election.[54][55] He brought his long-standing grievances about insufficient land for African people to the NRC meetings.[56] In August 1946, Luthuli, along with other councilors, objected to the government's use of force to quell a large strike by African mineworkers.[57][58] Luthuli accused the government of disregarding African complaints against their segregationist policies, and African councilors adjourned in protest.[57] He would later describe the NRC as a "toy telephone" requiring him to "shout a little louder" even though no one was listening.[59][60] The NRC reconvened later in 1946 but adjourned again indefinitely. Its members refused to co-operate with the government, which caused it to become ineffective.[61] The NRC never met after that point and it was disbanded by the government in 1952.[62][57]

Luthuli frequently addressed the criticism from black South Africans who believed that serving in the Native Representative Council would lead to nothing but talk, and that the NRC was a form of deceit served by the South African government.[55] He often agreed with these sentiments, but he and other contemporary African leaders believed that Africans should represent themselves in all structures created by the government, even if only to change them.[52] He was determined to take the demands and grievances of his people to the government. In the end, like others before him, Luthuli realized that his efforts were futile. In an interview with Drum Magazine in May 1953, Luthuli said that joining the NRC gave White South Africans "a last chance to prove their good faith" but they "had not done so".[59]

President of the Natal ANC

After John Dube suffered a stroke in 1945, Allison Champion succeeded him as Natal president in 1945 after defeating conservative leader Reverend A. Mtimkulu. During the election meeting, Luthuli was unexpectedly appointed as acting chair. Serving on Champion's executive, Luthuli remained politically active. However, the Youth League's adoption of a more confrontational Programme of Action in 1949 led to growing dissatisfaction with Champion's leadership, as he prioritised Natal's separateness over the new strategy. [63][64] Champion frequently failed to implement strategies and programmes set forth by the national ANC or Youth League, which made the Natal ANC lag behind.[65][64] Members of the Youth League in Natal nominated Luthuli for Natal president in 1951 as they viewed him as a new brand of leadership.[66][63] Luthuli and Champion were the two nominees for the election; Luthuli was elected president of the Natal ANC by a small majority.[67][68]

In Luthuli's first appearance as Natal ANC president at the ANC's national conference, he pleaded for more time to be given to the Natal ANC in preparation for the planned Defiance Campaign, a large act of civil disobedience by non-white South Africans.[68][63] Some members of the ANC did not support his request, and he was jeered at and labelled a coward.[69] However, Luthuli had no prior knowledge of this planned campaign and only found out about it as he was travelling to Bloemfontein, where the ANC's national conference was held.[70][68] Many of the details about the campaign were given to his predecessor, A.W.G Champion.[68] The Natal ANC agreed to prepare for the Defiance Campaign, which was slated for the latter half of 1952, and participate as soon as they were ready.[69][63]

Defiance Campaign

The preparations for the Defiance Campaign began on 6 April 1952, while the campaign itself was scheduled for 26 June 1952. The preparation day served as a warm-up, with large demonstrations in cities such as Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, East London, Pretoria, and Durban.[71] Concurrently, many White South Africans observed the three-hundredth anniversary of Jan van Riebeeck's landing at the Cape.[72]

Beginning in June, around 8500 volunteers[73] of the ANC and South African Indian Congress, who were carefully selected to follow the method of nonviolent resistance, deliberately set out to break the laws of apartheid.[69] Using strategies inspired by Gandhi, the Defiance Campaign required a strict adherence to a policy of nonviolence.[74] Africans, Indians, and Coloureds used amenities marked "Europeans Only"; they sat on benches and used reserved station platforms, carriages in trains, and post office counters.[75] Until the end of October, the Defiance Campaign remained nonviolent and disciplined. As the movement gained momentum, violence suddenly flared. The outbreaks were not a planned part of the campaign, and many, including Luthuli, believe it to be the work of provocateur agents.[76] The police, frustrated by the passive resistors, responded harshly when outbreaks of violence occurred, resulting in a chain reactions that caused dozens of Africans to be shot.[77]

Despite the efforts of the Defiance Campaign, the government's attitude remained unchanged, and they viewed the event as "communist-inspired" and a threat to law and order. This perception led to increased security measures and tighter controls. The Criminal Law Amendment Act allowed for individuals to be banned without trial, and the Public Safety Act allowed the government to suspend rule of law.[78] With more restrictions put in place, the ANC leaders decided to end the campaign in January 1953.[76]

Prior to the campaign, the ANC's membership numbered 25,000 in 1951. After the conclusion of the Campaign in 1953, it had increased to 100,000.[79][80] For the first time African, Indian, and Coloured communities across the country cooperated on a national scale.[80] The Defiance Campaign was also praised for its absence of violence. Even though there were thousands of protesters and some incidents of violence occurred, the low level of violence overall was a notable accomplishment.[81] Due to Luthuli's role in the Defiance Campaign as president of the Natal ANC, he was given an ultimatum by the government to choose between his work as a chief at Umvoti or his affiliation with the ANC.[82][83][84] He refused to choose, and the government deposed him as chief in November 1952.[45]

President-General of the ANC

In December 1952, Albert Luthuli was elected president general of the ANC with the support of the ANC Youth League (ANCYL)[85] and African communists.[86] Nelson Mandela was elected as his deputy. The ANCYL's support for Luthuli reflected its desire for a leader who would enact its programmes and goals, and marked a pattern of younger, more militant members within the ANC ousting presidents they deemed inflexible. The ANCYL had previously succeeded in removing Xuma, Moroka, and Champion when they no longer met their expectations.[87]

Luthuli led the ANC in its most difficult years; many of his executive members, such as Secretary-General Walter Sisulu, Moses Kotane, JB Marks, and David Bopape were either to be banned or imprisoned. The 1950s witnessed the erosion of black civil liberties, through the Treason Trial and the passage of the Suppression of Communism Act, which gave the police power to suppress government critics.[88]

First ban

On 30 May 1953, the government banned Luthuli for a year,[89][90] prohibiting him from attending any political or public gatherings and from entering major cities.[91] He was restricted to small towns and private meetings for the rest of 1953.[92] The Riotous Assemblies Act and the Criminal Law Amendment Act provided the legal framework for the issuing of banning orders. It was the first of four banning orders that Luthuli would receive as President-General of the ANC.[92] Following the expiration of his ban, Luthuli continued to attend and speak at anti-apartheid conferences.[93]

Second ban

In mid-1954, following the expiration of his ban, Luthuli was due to lead a protest in the Transvaal against the Western Areas Removals, a government scheme where close to 75,000 Africans were forced to move from Sophiatown and other townships. As he stepped off his plane in Johannesburg, the Special Branch handed him new banning orders,[94] not only prohibiting the attendance of meetings but confining him to the Groutville area for two years until July 1956.[95][96]

Congress of the People and Freedom Charter

In 1953, Z. K. Matthews proposed a large democratic convention, to be known as the Congress of the People, where all South Africans would be invited to create a Freedom Charter.[97][98] Despite complaints within the ANC from Africanists who believed the ANC should not work with other races, a multiracial organization, the Congress Alliance, was created as part of the preparation for the Congress of the People.[99][100] The alliance was led by the ANC and included the South African Indian Congress, Coloured Peoples Conference, Federation of South African Women, Congress of Trade Unions, and the Congress of Democrats.[101] Luthuli viewed the multiracial organisation as a way to bring freedom to South Africa.[101] After convening a secret meeting in December 1954 due to Luthuli's ban,[98] the Congress of the People took place in Kliptown, Johannesburg, in June 1955.[102][103]

Inspired by the values held in the United States Declaration of Independence and the UN Declaration of Human Rights, the Congress of the People developed the Freedom Charter, a list of demands for a democratic, multi-racial, and free South Africa.[104][105] While well-received by the attendants of the Congress of the People, the Africanist bloc of the ANC rejected it.[106] They opposed the multiracial nature of the charter and what they perceived as communist principles.[107][108] Although Luthuli recognised the socialist clauses in the Freedom Charter, he rejected any comparison to the communist ideology of the Soviet Union.[109] The ANC ratified the Charter at a conference one year after it was ratified by the Congress of the People.[110]

Luthuli was not able to attend the Congress of the People or the framing of the Freedom Charter due to a stroke and heart attack[104][111] as well as the banning order that confined him to Groutville.[104] In his absence, he was bestowed the honour of the Isitwalandwe,[112] which is awarded to individuals who have made significant contributions in the fight for freedom in South Africa.[103]

Treason Trial

After his second banning order expired in July 1956, he was arrested on 5 December and detained during the preliminary Treason Trial hearings in 1957.[113][114] Luthuli was one of 156 leaders who were arrested on charges of high treason due to their opposition to apartheid and the Nationalist Party government.[115][116] High treason carried the death penalty. One of the main charges against the African National Congress leaders were that they were involved in a communist conspiracy to overthrow the government. Anti-apartheid activists were often accused of being communists, and Luthuli was accustomed to such accusations and frequently dismissed them.[117]

The charges brought against the accused covered the period from 1 October 1952 to 13 December 1956, which included events such as the Defiance Campaign, Sophiatown removals protest, and the Congress of the People.[118] Following the preparatory examination period that began on 19 December 1956, all defendants were released on bail.[118] The pre-trial examination concluded in December 1957, resulting in charges being dropped against 65 of the accused, including Luthuli who was acquitted.[119][120] The trial for the remaining 91 accused individuals began in August 1958 as the Treason Trial commenced.[121] By 1959, only thirty of the accused remained.[122] The trial concluded on 29 March 1961 as all of the remaining defendants were found not guilty.[122][121]

Many of the lawyers who defended the accused were drawn by Luthuli and Z. K. Matthews being on trial. Their involvement contributed to raising global awareness and support for the accused.[123][124] The impression that Luthuli made on the foreigners who came to observe the trial led him to be suggested for the Nobel Peace Prize.[124]

Third ban and banning of the ANC

On 25 May 1959, the government served Luthuli his third banning order, which lasted for five years.[125] This ban prevented Luthuli from attending any meeting held within South Africa and confined him to his home district.[126] Luthuli's democratic values had been recognised by many white South Africans,[127] and he had gained a minor celebrity status among some white people, which caused the government to view him with more contempt.[128] When news of his ban spread, supporters of all races gathered to bid farewell to Luthuli.[129]

While Luthuli was still under a banning order, the ANC, led by Luthuli, announced an anti-pass campaign starting at the end of March 1960.[130] The recently created Pan-Africanist Congress, who split from the ANC because of their opposition to the ANC's multi-racial alliances, decided to jump ahead of the ANC's planned protest by ten days. On 21 March the PAC called for all African men to go to police stations and hand over their passbooks.[131] The peaceful march in Sharpeville resulted in sixty-nine people killed by police fire.[132] Additionally, three people were also killed in Langa.[133] Luthuli and several other ANC leaders ceremonially burned their passbooks in protest against the Sharpeville massacre.[134] Following a state of emergency and the passing of the Unlawful Organisations Act, the government banned the PAC and the ANC.[135] Luthuli and other political leaders were arrested and found guilty of burning their passbooks. In August, Luthuli was fined 100 pounds and initially sentenced to six months in jail. However, in September, this was later reduced to a three year suspended sentence on the condition that he would not be found guilty of a similar offense during that time.[136]

Following his return from prison to Groutville, Luthuli's power began to wane due to the banning of the ANC and the banning and imprisonment of supporting leaders, a decline in his health since his stroke and heart attack, and the rise of members in the ANC advocating for an armed struggle.[137] Duma Nokwe, Walter Sisulu, and Nelson Mandela, who had provided leadership for the ANC during South Africa's state of emergency, were determined to steer the ANC in a new direction. In May 1961, following a strike, they believed that "traditional weapons of protest… were no longer appropriate." They constantly evaluated whether the conditions were favourable to launch an armed resistance.[138]

uMkhonto we Sizwe

In June 1961, during a National Executive Committee Working Group session, Mandela proposed that the ANC adopt a self-defense platform. With the government's bans on the ANC and nonviolent protests, Mandela believed waiting for revolutionary conditions to arise, which was favoured by communist members, was not an option. Instead, the ANC had to adapt to their new underground conditions and draw inspiration from successful uprisings in Cuba, Algeria, and Vietnam.[139][140] Mandela argued that the ANC was the only anti-apartheid organisation that had the capacity to adopt an armed struggle and if they didn't take the lead, they would fall behind in their own movement.[141]

In July 1961, the ANC and Congress Alliance met to hold debates during an ANC NEC meeting surrounding the feasibility of Nelson Mandela's proposal of armed self-defence.[142] Luthuli did not support an armed struggle as he believed the ANC members were ill-prepared without modern firearms and battlefield experience.[143] In a following meeting a day later, a contentious back-and-forth arose. Supporters of armed defence believed the ANC was afraid and running from a physical fight while others believed counter-violence would provoke the government into arresting and killing them.[144][145]

While Luthuli did not support an armed struggle, he also did not oppose it.[141] According to Mandela, Luthuli suggested "two separate streams of the struggle": the ANC, which would remain nonviolent, and a "military movement [that] should be a separate and independent organ, linked to the ANC and under the overall control of the ANC, but fundamentally autonomous".[146] The formation of uMkhonto we Sizwe was part of a larger shift towards armed resistance in southern Africa. Other militant organisations were created in South West Africa, Mozambique, and Southern Rhodesia in the early 1960s.[147] The stated goal of uMkhonto we Sizwe was to cripple South Africa's economy without bloodshed and force the government into negotiating.[148] Mandela explained to Luthuli that only attacks against military installations, transportation links, and power plants would be carried out, which eased Luthuli's fears of the potential of loss of life.[148]

Nobel Peace Prize

In October 1961, during his most severe ban yet, Luthuli received the 1960 Nobel Peace Prize, becoming the first African to win the award.[149] He was awarded the prize for his use of nonviolent methods in his fight against racial discrimination. His nomination was put forward by Andrew Vance McCracken, the editor of Advance, a Congregational Church magazine.[150] His name was supported by Norwegian Socialist MPs who nominated him in February 1961.[150]

The Nobel Prize transformed Luthuli from being relatively unknown to a global celebrity. He received congratulatory letters from leaders of 25 countries, including U.S. President John F. Kennedy. In Groutville, journalists lined up to interview Luthuli who dedicated the award to the ANC and expressed gratitude to his wife Nokukhanya. He also used his newfound status as a global podium, and he pleaded to the UN and South Africa's trading partners to impose sanctions on Verwoerd's government.[151] His comments to the press made the world focus on apartheid and its effects on Africans.[150] During Luthuli's Nobel Peace Prize speech he spoke about the contribution of people among all races to find a peaceful solution to South Africa's race problem.[152] He went on to speak of how the "true patriots" of South Africa would not be satisfied until there were full democratic rights for everyone, equal opportunity, and the abolition of racial barriers.[153] Norwegian newspaper Arbeiderbladet described the effect of Luthuli's visit claiming: "We have suddenly begun to feel Africa's nearness and greatness."[154] The Times highlighted the strong impression that Luthuli made on the global stage following his appeal to end racial discrimination and establish an equal South Africa.[154] The day after Luthuli returned to South Africa from the award ceremony,[155] uMkhonto we Sizwe launched their first operations on 16 December 1961.[156]

The reaction from South Africa's government, as well as many White South Africans, was hostile. Luthuli still had to apply for permission to receive the prize in Oslo, Norway on 10 December 1961. Minister of the Interior, Jan de Klerk initially refused to issue Luthuli a passport but after intense domestic and international pressure, the government finally issued him one.[157] After he was granted permission and received his award, Eric Louw, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, rejected Luthuli's demands for universal suffrage and claimed that Luthuli's speech justified the government restricting his travel within South Africa.[150] The government-operated South African Broadcasting Corporation aired a defamatory broadcast about Luthuli. Volksblad argued the way Luthuli had "grasped every opportunity to besmirch South Africa was shocking".[150] The Star stated: "Mr. Luthuli demands a universal franchise, which is just as silly as restricting the vote to people of one colour and he asks the world to apply sanctions to his own country, which is as reckless and damaging as has been another leader's (HF Verwoerd) impetuous withdrawal from the commonwealth. Neither speaks for the authentic South African".[158] The belief that qualified franchise could be extended to Africans without accepting a democracy based on "one person, one vote" was the view of a majority of White South Africans.[159]

Luthuli received congratulations from some White South Africans, such as parliamentarian Jan Steytler and the Pietermaritzburg City Council. The Natal Daily News, a white-owned newspaper, described him as "a man with moral and intellectual qualities that have earned him the respect of the world and a position of leadership".[160] They also urged the government to "listen to the voice of responsible African opinion".[160] South African author and Liberal Party leader Alan Paton concluded that Luthuli was "the only man in South Africa who could lead both the left and the right ... both Africans and non-Africans".[161]

International popularity

Following his Nobel Peace Prize win, Luthuli was in a position of international renown for his nonviolence despite the concurrent sabotage operations of uMkhonto we Sizwe.[162][149][163] On 22 October 1962, University of Glasgow students elected Luthuli as Lord Rector in recognition of his "dignity and restraint".[164] The rectorship position was honorary. Luthuli's role would have been chair of the university court, the university's executive body, which met every month. Students elected Luthuli knowing he would serve in absentia. Although ceremonial, Luthuli's election was significant as he was the first African and first non-white person to be nominated as Rector. The South African government allegedly intercepted all mail from the University to Luthuli, an allegation the government denied.[165]

Luthuli's adherence to nonviolence also had support from his friend and civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr., who commended Luthuli's reputation and spoke of his admiration for Luthuli's "dedication to the cause of freedom and dignity".[166] In September 1962, King and Luthuli had issued the Appeal For Action Against Apartheid organised by the American Committee on Africa, which boosted solidarity between the anti-apartheid and civil rights movements and urged Americans to protest apartheid through nonviolent measures such as boycotts. In 1964, King became the youngest Nobel Peace Prize winner receiving the award for his nonviolent activism against racial discrimination, similar to Luthuli.[167] While travelling to Oslo to receive his Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, King stopped in London to give an "Address on South African Independence." The audience included Luthuli's exiled compatriots, citizens of different African countries, and human rights advocates from India , Pakistan , the West Indies, and the United States . King compared the racism in America to South Africa stating: "clearly there is much in Mississippi and Alabama to remind South Africans of their own country." He praised Luthuli for his leadership and identified "with those in a far more deadly struggle for freedom in South Africa." King anticipated that the withdrawal of all economic investments and trade from South Africa by the United States and United Kingdom would end apartheid and enable people of all races to build the society they want. During King's Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech on 10 December 1964, Luthuli received a special mention.[168] King called Luthuli a "pilot" of the freedom movement and claimed South Africa was the "most brutal expression of man's inhumanity to man".[169]

Artist Ronald Harrison, 22 years old at the time, unveiled his painting, The Black Christ, in 1962. Harrison portrayed Luthuli as Christ crucified on a cross. The painting was unveiled in St. Luke's Anglican Church in Salt River with the permission of Archbishop de Blank. The painting garnered controversy across South Africa. Along with Christ being depicted as Black, the two Roman soldiers resembled Prime Minister H. F. Verwoerd and Minister of Justice John Vorster. Minister of the Interior, Jan de Klerk, ordered the painting to be taken down and Harrison to appear before the Censorship Board. The Censorship Board banned the painting, deeming it disrespectful to religious sentiments. Following a CBS television documentary on the artwork, the government mandated its destruction.[170] Danish and Swedish supporters of the anti-apartheid movement smuggled the painting to Britain where, under Anglican priest John Collins' supervision, its display raised money for the International Defence and Aid Fund, a fund created to defend political prisoners.[171] Harrison was arrested and tortured by the Special Branch who intended on discovering who Harrison collaborated with to paint and display The Black Christ. He would later serve eight years of house arrest on charges related to his painting. Luthuli desired to meet Harrison after learning of his painting and its significance, and the Norwegian Embassy arranged a visit for Harrison to Luthuli. Norwegians took Harrison from Cape Town to Durban, and Harrison met Luthuli clandestinely in Groutville.[172]

Fourth ban

Effective 31 May 1964, John Vorster, the Minister of Justice, issued Luthuli a more severe banning order than the one he received in 1959. Unlike the previous ban, the new ban prevented Luthuli from travelling to the closest town of Stanger until 31 May 1969. Vorster believed that Luthuli's activism advanced communism, and he cautioned him against publishing any statements, making contact with banned individuals, or addressing gatherings.[173] NUSAS, the Liberal Party, and the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions publicly protested this banning order.[174] The ban increased Luthuli's isolation from the ANC, but he continued to share his message with the world through visitors such as United States Senator Robert F. Kennedy.[175] During Kennedy's 1966 tour of South Africa, he criticized white South Africa's racism and described apartheid as an abandonment of all that western civilization holds sacred.[176] He later flew by helicopter to Groutville to visit Luthuli where they discussed the anti-apartheid and civil rights movements. Kennedy later gave a press conference where he described Luthuli as one of the most impressive men he had ever met.[177]

— Luthuli's wife, Nokukhanya, on his declining health.[178]

Luthuli's political and physical activity declined significantly in the period leading up to his death.[179] During the 33 months from October 1964 until his passing in July 1967, there are only a few archival records produced by Luthuli's hand, which consist of sermon notes and medical reminders scribbled on scraps of paper. These notes suggest that Luthuli had little contact with others during the last six months of his life and focused primarily on religious matters, including dates of service and scripture readings. Although it is not certain, it appears that Luthuli's mental state may have been declining, as his handwriting became increasingly difficult to decipher. There are no archival records from his last two years of life, casting doubt on his ability to function as the President-General of the ANC or pose a political threat to the government.[179] Newspaper articles reported that Luthuli's ability to read and write had significantly declined, and he devoted most of his time listening to radio broadcasts.[180] According to The Sunday Times, Luthuli underwent delicate surgery on his left eye at McCord Zulu Hospital, and as a result, he was granted a suspension of his banning orders. The eye had been causing him constant pain and had been 'virtually useless' ever since his stroke in 1955. The pain caused by the eye had been a long-standing issue, and doctors had even discussed with Luthuli the option of removing it.[180] According to other newspaper articles, Luthuli was facing more health issues than just his eye problem. He stayed in the hospital for up to four weeks, and other health concerns, including high blood pressure, may have extended his stay. The fact that he drafted and signed his will immediately before his hospitalization raise doubts about the common belief that Luthuli was in good health leading up to his death.[181]

Death

On Friday 21 July 1967, Luthuli left his house at 08:30 and informed his wife that he would be walking to his store near Gledhow train station. Luthuli traveled from his house to his store and back daily. An hour later at 09:30, he arrived at his store where he delivered a package to his employee.[182] Around 10:00, Luthuli left his store and told his store employee that he was going to his field, and would return later. Forty minutes later Luthuli crossed the river again to return to his store without having met with any of his field workers. On his way back to his store, Luthuli was struck by a goods train.[183]

— Nokukhanya recounts her and Luthuli's argument a day before his death.[184]

At 10:29, a goods train pulled by a locomotive left Stanger for Durban. Aboard the train were the driver, conductor, and fireman. At 10:36 the train passed Gledhow station without stopping. Two minutes later at 10:38, the train began to cross the Umvoti River railway bridge. Someone entering the bridge would have passed a sign that read, "Cross This Bridge At Their Own Risk" in English and Afrikaans. The driver indicated in his testimony that he blew the whistle from the time he saw Luthuli walking towards the train until the train hit him.[183] The driver informed the fireman that the train had hit someone, and the driver testified that he immediately applied the brakes and brought the train to a halt.[185] The driver and the fireman left the train and attended to Luthuli, who was still alive and breathing despite having received head injuries. Luthuli was brought to Stanger Hospital at approximately 11:50, where the Senior Medical Superintendent described his condition as "semi-conscious" and "bleeding freely" due to injuries sustained to his head.[186]

For two and a half hours, from 11:50 to 14:20, the doctors treated Luthuli's wounds by giving a blood transfusion and providing heart stimulant medication. Around 13:00, Luthuli's son, Christian, arrived at the hospital to see Luthuli who was still conscious.[186] Christian informed Nokukhanya about Luthuli's potential relocation to King Edward VIII Hospital in Durban, prompting her to search for him there. At Stanger Hospital, Luthuli's condition started to deteriorate despite treatment. It was then decided to not transfer Luthuli to a different hospital due to his worsening condition.[187] Instead, a neurosurgeon from Durban would come to Stanger Hospital. Upon hearing the news, Nokukhanya travelled to Stanger. At 14:20, neurosurgeon Mauritius Joubert arrived at Stanger Hospital. He found Luthuli in a coma not responding to stimulation.[188] Five minutes after his examination, at 14:25, Luthuli died. Nokukhanya arrived at the hospital five minutes after his death without having said goodbye to him.[189]

Reaction

After learning of Luthuli's death, people around the world immediately suspected foul play from the South African government.[189] Despite a formal inquest concluding he was killed by a train, speculation remained rampant and still carries on years after his death.[190] As soon as they learned about Luthuli's death, the ANC and its allies suspected that the South African government was responsible for it. The Zimbabwe African People's Union repeated the same claims in Sechaba, the official organ of the ANC.[190] The Tanganyika African National Union described Luthuli's death as "dubious".[190] In a letter to the ANC, vice-president of FRELIMO, Uria Simango, claimed Luthuli's death was premeditated.[191] Many of Luthuli's family members believe that he was deliberately killed. Daughters Thandeka and Albertinah both maintained that he was murdered in the decades following his death.[192][193] Albert Luthuli biographer, Scott Everett Couper, states that the myth of Luthuli being killed leads to an inaccurate portrayal of Luthuli, stating: "To say that Luthuli was mysteriously killed is to understand that he still had a vital role in the struggle for liberation at the time of his death, that he was a threat to the apartheid regime. Sadly, Luthuli had long since been considered obsolete by leaders of his own movement and he had little contact with those imprisoned, banned or exiled. Since Sharpeville ... Luthuli served only as the honorary, emeritus, titular leader of the ANC".[194]

See also

- International Fellowship of Reconciliation

- List of black Nobel laureates

- List of people subject to banning orders under apartheid

Notes

Citations

- ↑ Jain, Chelsi. "United Nations Prize in the Field of Human Rights". https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Events/HRPrizepreviouswinners.pdf.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Luthuli 1962, p. 24.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Vinson 2018, p. 15.

- ↑ Woodson 1986, p. 345.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 8.

- ↑ Luthuli 1962, p. 23.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Vinson 2018, p. 16.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 7.

- ↑ Luthuli 1962, p. 25.

- ↑ Kumalo 2009, p. 2.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Vinson 2018, p. 18.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Benson 1963, p. 4.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, pp. 16, 18.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 19.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Benson 1963, p. 6.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Luthuli 1962, p. 28.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Vinson 2018, p. 29.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Vinson 2018, p. 20.

- ↑ Luthuli 1962, p. 29.

- ↑ Luthuli 1962, p. 30.

- ↑ Luthuli 1962, pp. 32.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Benson 1963, p. 7.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 20-21.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Vinson 2018, p. 21.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Luthuli 1962, pp. 43.

- ↑ Benson 1963, p. 8.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 37.

- ↑ Couper 2010, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 38.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 39.

- ↑ Marks 1989, p. 217.

- ↑ Couper 2010, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 28.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Luthuli 1962, p. 66.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Couper 2010, p. 42.

- ↑ Luthuli 1962, p. 67.

- ↑ Couper 2010, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Couper 2010, p. 43.

- ↑ Legum 1968, p. 54.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 24.

- ↑ Pillay 2012, p. 7.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Pillay 2012, p. 8.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Vinson 2018, p. 25.

- ↑ Woodson 1986, p. 346.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Vinson 2018, p. 45.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 58.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Vinson 2018, p. 27.

- ↑ Woodson 1986, p. 347.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Luthuli 1962, p. 93.

- ↑ Luthuli 1962, p. 94.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Luthuli 1962, p. 103.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 46.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Vinson 2018, p. 30.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Luthuli 1962, p. 102.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 Vinson 2018, p. 31.

- ↑ Evans 1997, p. 187.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Pillay 2012, p. 11.

- ↑ Benson 1963, p. 15.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 47.

- ↑ Luthuli 1962, p. 105.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 63.3 Pillay 2012, p. 12.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Couper 2010, p. 53.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 39.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 54.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 40.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 68.3 Benson 1963, p. 18.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Couper 2010, p. 55.

- ↑ Luthuli 1962, p. 112.

- ↑ Luthuli 1962, p. 116.

- ↑ Luthuli 1962, p. 115.

- ↑ Legum 1968, p. 59.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 41.

- ↑ Legum 1968, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Couper 2010, p. 56.

- ↑ Legum 1968, p. 60.

- ↑ Pillay 2012, p. 14.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Pillay 2012, p. 15.

- ↑ Pillay 2012, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Pillay 2012, p. 16.

- ↑ Legum 1968, p. 61.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 47.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 75.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 62.

- ↑ Pillay 2012, p. 17.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 51.

- ↑ Legum 1968, p. 63.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 51-52.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Couper 2010, p. 66.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 67.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 55.

- ↑ Pillay 2012, p. 19.

- ↑ Benson 1963, p. 26.

- ↑ Pillay 2012, p. 63.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Vinson 2018, p. 60.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 43.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 Vinson 2018, p. 59.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Couper 2010, p. 69.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 Vinson 2018, p. 61.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 62.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 63.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 64.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 65.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 66.

- ↑ Benson 1963, p. 27.

- ↑ Benson 1963, p. 28.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 72.

- ↑ Pillay 2012, p. 21.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Benson 1963, p. 29.

- ↑ Legum 1968, p. 64.

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 Couper 2010, p. 73.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Callinicos 2004, p. 235.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 Couper 2010, p. 74.

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 Vinson 2018, p. 77.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 76.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 Benson 1963, p. 32.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 83.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 82.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 80.

- ↑ Benson 1963, p. 38.

- ↑ Legum 1968, p. 66.

- ↑ Benson 1963, p. 42.

- ↑ Benson 1963, p. 43.

- ↑ Pillay 2012, p. 22.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 86.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 87.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 91.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 94.

- ↑ Pillay 2012, p. 154.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 102.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 102.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, pp. 102–103.

- ↑ 141.0 141.1 Vinson 2018, p. 103.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, pp. 104–105.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 105.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 107.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 108.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 106.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ 148.0 148.1 Vinson 2018, p. 109.

- ↑ 149.0 149.1 Vinson 2018, p. 11.

- ↑ 150.0 150.1 150.2 150.3 150.4 Pillay 2012, p. 25.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 110.

- ↑ Benson 1963, p. 52.

- ↑ Benson 1963, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ 154.0 154.1 Benson 1963, p. 57.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 135.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 118.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 112.

- ↑ Pillay 2012, pp. 25–27.

- ↑ Pillay 2012, p. 27.

- ↑ 160.0 160.1 Vinson 2018, p. 111.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 117.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 13.

- ↑ Pillay 2012, p. 29.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 165.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 169.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 166.

- ↑ Baldwin 1992, p. 201.

- ↑ Nesbitt 2004, p. 62.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 163.

- ↑ Couper 2010, pp. 163–164.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 164.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 185.

- ↑ Couper 2010, pp. 185–186.

- ↑ Vinson 2018, p. 130.

- ↑ Couper 2010, pp. 183–184.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 184.

- ↑ Rule 1993, p. 137.

- ↑ 179.0 179.1 Couper 2010, p. 186.

- ↑ 180.0 180.1 Couper 2010, p. 187.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 188.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 189.

- ↑ 183.0 183.1 Couper 2010, p. 190.

- ↑ Rule 1993, p. 140.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 191.

- ↑ 186.0 186.1 Couper 2010, p. 192.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 193.

- ↑ Couper 2010, pp. 193–194.

- ↑ 189.0 189.1 Couper 2010, p. 194.

- ↑ 190.0 190.1 190.2 Couper 2010, p. 195.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 196.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 198.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 199.

- ↑ Couper 2010, p. 203.

References

- Baldwin, Lewis (1992). To Make the Wounded Whole: The Cultural Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. Augsburg Fortress Publishers. ISBN 9780800625436. https://books.google.com/books?id=lmV2AAAAMAAJ&q=lewis+baldwin+book+1992. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- Benson, Mary (1963). Chief Albert Lutuli of South Africa. Oxford University Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZIowAAAAIAAJ.

- Callinicos, Luli (2004). Oliver Tambo: Beyond the Engeli Mountains. David Philip Publishers. ISBN 978-0864866660. https://books.google.com/books?id=GtWgrbO7CXEC. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- Couper, Scott (11 October 2010). Albert Luthuli: Bound by Faith. University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. ISBN 9781869141929. https://books.google.com/books?id=RrPOSAAACAAJ. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- Evans, Ivan (1997). Bureaucracy and Race. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520206519. https://books.google.com/books?id=b2JRngEACAAJ. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- Kumalo, Simangaliso (2009). "Faith and politics in the context of struggle: The legacy of Inkosi Albert John Luthuli's Christian-centred political leadership". Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 35: 1–13. ISSN 2412-4265.

- Legum, Colin (1968). The Bitter Choice: Eight South Africans' Resistance to Tyranny. The World Publishing Company. https://books.google.com/books?id=MA0BAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- Luthuli, Albert (1 January 1962). Let My People Go. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0070391208. https://books.google.com/books?id=pkgKAQAAIAAJ. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- Marks, Shula (1989). "Patriotism, Patriarchy and Purity: Natal and the Politics of Zulu Ethnic Consciousness". in Vail, Leroy. The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520074200.

- Nesbitt, Francis (2004). Race for Sanctions. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253342324. https://books.google.com/books?id=dN4w_FQRb1EC. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- Pillay, Gerald (2012). Voices of Liberation: Albert Luthuli. HSRC Press. ISBN 978-0-7969-2356-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=LmfyugAACAAJ. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- Rule, Peter (1993). Nokukhanya, Mother of Light. Grail. ISBN 9780620172592. https://books.google.com/books?id=0o9GAQAAIAAJ&q=nokukhanya+mother+of+light. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- Vinson, Robert Trent (9 August 2018). Albert Luthuli. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-4642-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=4XdlDwAAQBAJ. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Woodson, Dorothy C. (1986). "Albert Luthuli and the African National Congress: A Bio-Bibliography". History in Africa 13: 345–362. doi:10.2307/3171551. ISSN 0361-5413.

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Viscount Hailsham |

Rector of the University of Glasgow 1962–1965 |

Succeeded by Baron Reith |

| Cultural offices | ||

| Preceded by Martin Lutuli |

Chief of Christian Zulus inhabiting the Umvoti River Reserve 1936–1952 |

Chieftaincy discontinued |

{{Navbox | name = Nobel Peace Prize laureates | state = autocollapse | bodyclass = hlist | title = Laureates of the Nobel Peace Prize | nowrapitems = yes

| group1 = 1901–1925 | list1 =

- 1901: [[Biography:Henry DunHenry Dunant / Frédéric Passy

- 1902: Élie Ducommun / Charles Gobat

- 1903: Randal Cremer

- 1904: Institut de Droit International

- 1905: Bertha von Suttner

- 1906: Theodore Roosevelt

- 1907: Ernesto Moneta / Louis Renault

- 1908: Klas Arnoldson / Fredrik Bajer

- 1909: A. M. F. Beernaert / Paul Estournelles de Constant

- 1910: International Peace Bureau

- 1911: Tobias Asser / Alfred Fried

- 1912: Elihu Root

- 1913: Henri La Fontaine

- 1914

- 1915

- 1916

- 1917: International Committee of the Red Cross

- 1918

- 1919: Woodrow Wilson

- 1920: Léon Bourgeois

- 1921: Hjalmar Branting / Christian Lange

- 1922: Fridtjof Nansen

- 1923

- 1924

- 1925: Austen Chamberlain / Charles Dawes

| group2 = 1926–1950 | list2 =

- 1926: Aristide Briand / Gustav Stresemann

- 1927: Ferdinand Buisson / Ludwig Quidde

- 1928

- 1929: Frank B. Kellogg

- 1930: Nathan Söderblom

- 1931: Jane Addams / Nicholas Butler

- 1932

- 1933: Norman Angell

- 1934: Arthur Henderson

- 1935: Carl von Ossietzky

- 1936: Carlos Saavedra Lamas

- 1937: Robert Cecil

- 1938: Nansen International Office for Refugees

- 1939

- 1940

- 1941

- 1942

- 1943

- 1944: International Committee of the Red Cross

- 1945: Cordell Hull

- 1946: Emily Balch / John Mott

- 1947: Friends Service Council / American Friends Service Committee

- 1948

- 1949: John Boyd Orr

- 1950: Ralph Bunche

| group3 = 1951–1975 | list3 =

- 1951: Léon Jouhaux

- 1952: Albert Schweitzer

- 1953: George Marshall

- 1954: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

- 1955

- 1956

- 1957: Lester B. Pearson

- 1958: Georges Pire

- 1959: Philip Noel-Baker

- 1960: Albert Lutuli

- 1961: Dag Hammarskjöld

- 1962: Linus Pauling

- 1963: International Committee of the Red Cross / League of Red Cross Societies

- 1964: Martin Luther King Jr.

- 1965: UNICEF

- 1966

- 1967

- 1968: René Cassin

- 1969: International Labour Organization

- 1970: Norman Borlaug

- 1971: Willy Brandt

- 1972

- 1973: Lê Đức Thọ (declined award) / Henry Kissinger

- 1974: Seán MacBride / Eisaku Satō

- 1975: Andrei Sakharov

| group4 = 1976–2000 | list4 =

- 1976: Betty Williams / Mairead Corrigan

- 1977: Amnesty International

- 1978: [[Biography:Anwar SaAnwar Sadat{{\}}Menachem Begin

- 1979: Mother Teresa

- 1980: Adolfo Pérez Esquivel

- 1981: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

- 1982: Alva Myrdal / Alfonso García Robles

- 1983: Lech Wałęsa

- 1984: Desmond Tutu

- 1985: International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War

- 1986: Elie Wiesel

- 1987: Óscar Arias

- 1988: UN Peacekeeping Forces

- 1989: Tenzin Gyatso (14th Dalai Lama)

- 1990: Mikhail Gorbachev

- 1991: Aung San Suu Kyi

- 1992: Rigoberta Menchú

- 1993: Nelson Mandela / F. W. de Klerk

- 1994: Shimon Peres / Yitzhak Rabin / Yasser Arafat

- 1995: Pugwash Conferences / Joseph Rotblat

- 1996: Carlos Belo / José Ramos-Horta

- 1997: International Campaign to Ban Landmines / Jody Williams

- 1998: John Hume / David Trimble

- 1999: Médecins Sans Frontières

- 2000: Kim Dae-jung

| group5 = 2001–present | list5 =

- 2001: United Nations / Kofi Annan

- 2002: Jimmy Carter

- 2003: Shirin Ebadi

- 2004: Wangari Maathai

- 2005: International Atomic Energy Agency / Mohamed ElBaradei

- 2006: Grameen Bank / Muhammad Yunus

- 2007: Al Gore / Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- 2008: Martti Ahtisaari

- 2009: Barack Obama

- 2010: Liu Xiaobo

- 2011: Ellen Johnson Sirleaf / Leymah Gbowee / Tawakkol Karman

- 2012: European Union

- 2013: Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons

- 2014: Kailash Satyarthi / Malala Yousafzai

- 2015: Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet

- 2016: Juan Manuel Santos

- 2017: International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons

- 2018: Denis Mukwege / Nadia Murad

- 2019: Abiy Ahmed

}}

|