Biology:Clathrus ruber

| Clathrus ruber | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Phallales |

| Family: | Phallaceae |

| Genus: | Clathrus |

| Species: | C. ruber

|

| Binomial name | |

| Clathrus ruber P.Micheli ex Pers. (1801)

| |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

| Mycological characteristics | |

| glebal hymenium | |

| no distinct cap | |

| hymenium attachment is not applicable | |

| stipe has a volva | |

| spore print is olive to olive-brown | |

| ecology is saprotrophic | |

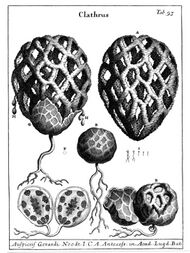

Clathrus ruber is a species of fungus in the family Phallaceae, and the type species of the genus Clathrus. It is commonly known as the latticed stinkhorn, the basket stinkhorn, or the red cage, alluding to the striking fruit bodies that are shaped somewhat like a round or oval hollow sphere with interlaced or latticed branches. The fungus is saprobic, feeding off decaying woody plant material, and is often found alone or in groups in leaf litter on garden soil, grassy places, or on woodchip garden mulches. Although considered primarily a European species, C. ruber has been introduced to other areas, and now has a wide distribution that includes all continents except Antarctica. The species was illustrated in the scientific literature during the 16th century, but was not officially described until 1729.

The fruit body initially appears like a whitish "egg" attached to the ground at the base by cords called rhizomorphs. The egg has a delicate, leathery outer membrane enclosing the compressed lattice that surrounds a layer of olive-green spore-bearing slime called the gleba, which contains high levels of calcium that help protect the fruit body during development. As the egg ruptures and the fruit body expands, the gleba is carried upward on the inner surfaces of the spongy lattice, and the egg membrane remains as a volva around the base of the structure. The fruit body can reach heights of up to 20 cm (7.9 in). The color of the fruit body, which can range from pink to orange to red, results primarily from the carotenoid pigments lycopene and beta-carotene. The gleba has a fetid odor, somewhat like rotting meat, which attracts flies and other insects to help disperse its spores. Although the edibility of the fungus is not known with certainty, its odor would deter most from consuming it. C. ruber was not regarded highly in tales in southern European folklore, which suggested that those who handled the mushroom risked contracting various ailments.

Taxonomy, phylogeny, and naming

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogeny and relationships of C. ruber and selected Phallaceae species based on ribosomal DNA sequences[3] |

Clathrus ruber was illustrated in 1560 by the Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner in his Nomenclator Aquatilium Animantium—Gesner mistook the mushroom for a marine organism.[4] It appeared in a woodcut in John Gerard's 1597 Great Herball,[5] shortly thereafter in Carolus Clusius' 1601 Fungorum in Pannoniis Observatorum Brevis Historia,[6] and was one of the species featured in Cassiano dal Pozzo's museo cartaceo ("paper museum") that consisted of thousands of illustrations of the natural world.[7]

The fungus was first described scientifically in 1729, by the Italian Pier Antonio Micheli in his Nova plantarum genera iuxta Tournefortii methodum disposita, who gave it its current scientific name.[8] The species was once referred to by American authors as Clathrus cancellatus L., as they used a system of nomenclature based on the former American Code of Botanical Nomenclature, in which the starting point for naming species was Linnaeus's 1753 Species Plantarum. The International Code for Botanical Nomenclature now uses the same starting date, but names of Gasteromycetes used by Christian Hendrik Persoon in his Synopsis Methodica Fungorum (1801) are sanctioned and automatically replace earlier names. Since Persoon used the specific epithet ruber, the correct name for the species is Clathrus ruber. Several historical names of the fungus are now synonyms: Clathrus flavescens, named by Persoon in 1801;[9] Clathrus cancellatus by Joseph Pitton de Tournefort and published by Elias Fries in 1823;[10] Clathrus nicaeensis, published by Jean-Baptiste Barla in 1879;[11] and Clathrus ruber var. flavescens, published by Livio Quadraccia and Dario Lunghini in 1990.[12][13]

Clathrus ruber is the type species of the genus Clathrus, and is part of the group of Clathrus species known as the Laternoid series. Common features uniting this group include the vertical arms of the receptacle (fruit body) that are not joined together at the base, and the spongy structure of the receptacle.[14] According to a molecular analysis published in 2006, out of the about 40 Phallales species used in the study, C. ruber is most closely related to Aseroe rubra, Clathrus archeri, Laternea triscapa, and Clathrus chrysomycelinus.[3]

The generic name Clathrus is derived from Ancient Greek κλειθρον or "lattice", and the specific epithet is Latin ruber, meaning "red".[15] The mushroom is commonly known as the "basket stinkhorn",[16] the "lattice stinkhorn",[17] or the "red cage".[18] It was known to the locals of the Adriatic hinterland in the former Yugoslavia as veštičije srce or vještičino srce, meaning "witch's heart".[19] This is still the case in parts of rural France, where it is known as cœur de sorcière.[20]

Description

Before the volva opens, the fruiting body is egg-shaped to roughly spherical, up to 6 cm (2.4 in) in diameter, with a gelatinous interior up to 3 mm (0.1 in) thick. White to grayish in color, it is initially smooth, but develops a network of polygonal marks on the surface prior to opening as the internal structures expand and stretch the peridium taut.[21] The fruit body, or receptacle, bursts the egg open as it expands (a process that can take as little as a few hours),[6] and leaves the remains of the peridium as a cup or volva surrounding the base.[21] The receptacle ranges in color from red to pale orange, and it is often lighter in color approaching the base. The color appears to be dependent upon the temperature and humidity of the environment.[22] The receptacle consists of a spongy network of "arms" interlaced to make meshes of unequal size. At the top of the receptacle, the arms are up to 1.5 cm (0.6 in) thick, but they taper down to smaller widths near the base. A cross-section of the arm reveals it to be spongy, and made up of one wide inner tube and two indistinct rows of tubes towards the outside. The outer surface of the receptacle is ribbed or wrinkled.[21] There are between 80 and 120 mesh holes in the receptacle.[23] The unusual shape of the receptacle has inspired some creative comparisons: David Arora likened it to a whiffleball,[22] while the German Mycological Society—who named C. ruber the 2011 "Mushroom of the Year"—described it as "like an alien from a science fiction horror film".[24]

A considerable variation in height has been reported for the receptacle, ranging from 8 to 20 cm (3.1 to 7.9 in) tall.[6] The base of the fruit bodies are attached to the substrate by rhizomorphs (thickened cords of mycelia). The dark olive-green to olive-brown, foul-smelling sticky gleba covers the inner surface of the receptacle, except near the base. The odor—described as resembling rotting meat[25][26]—attracts flies, other insects, and, in one report, a scarab beetle (Scarabaeus sacer)[27] that help disperse the spores.[22][28] The putrid odor—and people's reaction to it—have been well documented. In 1862 Mordecai Cubitt Cooke wrote "it is recorded of a botanist who gathered one for the purpose of drying it for his herbarium, that he was compelled by the stench to rise during the night and cast the offender out the window."[29] American mycologist David Arora called the odor "the vilest of any stinkhorn".[22] The receptacle collapses about 24 hours after its initial eruption from the egg.[6]

The spores are elongated, smooth, and have dimensions of 4–6 by 1.5–2 µm.[21] Scanning electron microscopy has revealed that C. ruber (in addition to several other Phallales species) has a hilar scar—a small indentation in the surface of the spore where it was previously connected to the basidium via the sterigma.[30] The basidia (spore-bearing cells) are six-spored.[31]

Similar species

Clathrus ruber may be distinguished from the closely related tropical species C. crispus by the absence of the corrugated rims which surround each mesh of the C. crispus fruit body.[32] The phylogenetically close species C. chrysomycelinus has a yellow receptacle with arms that are structurally simpler, and its gleba is concentrated on specialized "glebifers" located at the lattice intersections. It is known only from Venezuela to southern Brazil.[21] Clathrus columnatus has a fruit body with two to five long vertical orange or red spongy columns, joined together at the apex.[33]

Edibility and folklore

Although edibility for C. ruber has not been officially documented, its foul smell would dissuade most people from eating it. In general, stinkhorn mushrooms are considered edible when still in the egg stage, and are even considered delicacies in some parts of Europe and Asia, where they are pickled raw and sold in markets as "devil's eggs".[22] An 1854 report provides a cautionary tale to those considering consuming the mature fruit body. Dr. F. Peyre Porcher, of Charleston, South Carolina, described an account of poisoning caused by the mushroom:

A young person having eaten a bit of it, after six hours suffered from a painful tension of the lower stomach, and violent convulsions. He lost the use of his speech, and fell into a state of stupor, which lasted for forty-eight hours. After taking an emetic he threw up a fragment of the mushroom, with two worms, and mucus, tinged with blood. Milk, oil, and emollient fomentations, were then employed with success.[34]

C. ruber is generally listed as inedible or poisonous in many British mushroom publications from 1974 to 2008.

British mycologist Donald Dring, in his 1980 monograph on the family Clathraceae, wrote that C. ruber was not regarded highly in southern European folklore. He mentions a case of poisoning following its ingestion, reported by Barla in 1858, and notes that Ciro Pollini reported finding it growing on a human skull in a tomb in a deserted church.[21] According to John Ramsbottom, Gascons consider the mushroom a cause of cancer;[35] they will usually bury specimens they find.[6] In other parts of France it has been reputed to produce skin rashes or cause convulsions.[35]

Ecology, habitat, and distribution

Like most of the species of the order Phallales, Clathrus ruber is saprobic—a decomposer of wood and plant matter—and is commonly found fruiting in mulch beds.[36] The fungus grows alone or clustered together near woody debris, in lawns, gardens, and cultivated soil.[37]

Clathrus ruber was originally described by Micheli from Italy. It is considered native to southern and central continental Europe, as well as Macaronesia (the Azores[21] and the Canary Islands[38]), western Turkey,[39] North Africa (Algeria), and western Asia (Iran).[21] The fungus is rare in central Europe,[19] and is listed in the Red data book of Ukraine.[40]

The fungus has probably been introduced elsewhere, often because of the use of imported mulch used in gardening and landscaping.[37] It may have extended its range northwards into the British Isles or been introduced in the nineteenth century.[41] It now has a mainly southerly distribution in England and has been recorded from Cornwall,[42] Devon,[43] Dorset, Somerset,[21] the Isle of Wight,[44] Hampshire, Berkshire, Sussex, Surrey, and Middlesex. In Scotland, it has been recorded from Argyll. It is also known from Wales, the Channel Islands,[21] and Ireland.[45] The fungus also occurs in the United States (California , Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Alabama, Virginia, North Carolina, and New York),[46] Canada, Mexico, and Australasia.[47] The species was also reported from South America (Argentina).[48] In China, it has been collected from Guangdong, Sichuan, Guizhou, and Tibet.[23] Records from Japan[49] are referable to Clathrus kusanoi; records from the Caribbean are probably of C. crispus.[21]

Biochemistry

Like other stinkhorn fungi, C. ruber bioaccumulates the element manganese. It has been postulated that this element plays a role in the enzymatic breakdown of the gleba with simultaneous formation of odorous compounds. Compounds like dimethyl sulfide, aldehydes, and amines—which contribute to the disagreeable odor of the gleba—are produced by the enzymatic decarboxylation of keto acids and amino acids, but the enzymes will only work in the presence of manganese.[6] A chemical analysis of the elemental composition of the gelatinous outer layer, the embryonic receptacle and the gleba showed the gelatinous layer to be richest in potassium, calcium, manganese, and iron ions. Calcium ion stabilizes the polysaccharide gel, protecting the embryonic receptacle from drying out during the growth of the egg. Potassium is required for the gelatinous layer to retain its osmotic pressure and retain water; high concentrations of the element are needed to support the rapid growth of the receptacle. The high concentration of elements suggests that the gelatinous layer has a "placenta-like" function—serving as a reservoir from which the receptacle may draw upon as it rapidly expands.[6]

Pigments responsible for the orange to red colors of the mature fruit bodies have been identified as carotenes, predominantly lycopene and beta-carotene—the same compounds responsible for the red and orange colors of tomatoes and carrots, respectively. Lycopene is also the main pigment in the closely related fungus Clathrus archeri, while beta-carotene is the predominant pigment in the Phallaceae species Mutinus caninus, M. ravenelii, and M. elegans.[50]

References

- ↑ "Clathrus ruber P. Micheli ex Pers.". Index Fungorum. CAB International. http://www.speciesfungorum.org/Names/SynSpecies.asp?RecordID=232782.

- ↑ "Clathrus ruber P. Micheli ex Pers. 1801". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. http://www.mycobank.org/MycoTaxo.aspx?Link=T&Rec=232782.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Molecular phylogenetics of the gomphoid-phalloid fungi with an establishment of the new subclass Phallomycetidae and two new orders". Mycologia 98 (6): 949–55. 2006. doi:10.3852/mycologia.98.6.949. PMID 17486971.

- ↑ Holthius LB (1996). "Original watercolours donated by Cornelius Sittardus to Conrad Gesner, and published by Gesner in his (1558–1670) works on aquatic animals" (PDF). Zoologische Mededelingen 70 (11): 169–96. http://www.repository.naturalis.nl/document/149204.

- ↑ Paul D. (1918). "Presidential address. On the earlier study of fungi in Britain". Transactions of the British Mycological Society 6 (2): 91–103. doi:10.1016/s0007-1536(17)80018-8. http://www.cybertruffle.org.uk/cyberliber/59351/0006/002/0094.htm. Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Stijve T. (1997). "Close encounters with Clathrus ruber, the latticed stinkhorn". The Australasian Mycologist 16 (1): 11–15. http://australasianmycology.com/pages/pdf/16/1/11.pdf.

- ↑ The Paper Museum of Cassiano dal Pozzo. Series B: Natural History. Fungi. London, UK: Harvey Miller Publishers. 2006. plates 96–100. ISBN 1-905375-05-0.

- ↑ Micheli PA (1729) (in Latin). Nova plantarum genera iuxta Tournefortii methodum disposita. Florence, Italy: Typis Bernardi Paperinii. p. 214. https://books.google.com/books?id=4fKcfjHL5OUC&pg=RA1-PA10.

- ↑ "Clathrus flavescens Pers. 1801". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. http://www.mycobank.org/MycoTaxo.aspx?Link=T&Rec=233176.

- ↑ Fries EM (1823) (in Latin). Systema Mycologicum. 2. Lundin, Sweden: Ex Officina Berlingiana. p. 288. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/4335393.

- ↑ "Clathrus nicaeensis Barla". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. http://www.mycobank.org/MycoTaxo.aspx?Link=T&Rec=233817.

- ↑ "Contributo alla conoscenza dei macromiceti della tenuta Presidenziale di Castelporziano (Micoflora del Lazio II)" (in Italian). Quaderni dell'Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei 264: 49–120. 1990.

- ↑ "Clathrus ruber var. flavescens(Pers.) Quadr. & Lunghini". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. http://www.mycobank.org/MycoTaxo.aspx?Link=T&Rec=127436.

- ↑ "Clathrus P. Micheli ex L. 1753". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. http://www.mycobank.org/MycoTaxo.aspx?Link=T&Rec=19069.

- ↑ Rea C. (1922). British Basidiomycetes: A Handbook to the Larger British Fungi. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 21. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/17127837.

- ↑ Phillips R. "Clathrus ruber". Rogers Mushrooms. Rogers Plants Ltd.. http://www.rogersmushrooms.com/gallery/DisplayBlock~bid~6941.asp.

- ↑ A Field Guide to Mushrooms: North America. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin. 1987. p. 345. ISBN 0-395-91090-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=kSdA3V7Z9WcC&pg=PA345.

- ↑ "Recommended English Names for Fungi in the UK". British Mycological Society. http://www.fungi4schools.org/Reprints/ENGLISH_NAMES.pdf.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "First record of Clathrus ruber from Serbia". Mycologia Balcanica 1: 59–60. 2003.

- ↑ (in French) A la recherche des champignons - 2e. éd.: Un guide de terrain pour comprendre la nature – Champignons de nos forêts, sachez les reconnaître. Dunod. 2014. p. 166. ISBN 978-2-10-071799-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=CzzGCQAAQBAJ&pg=PT166.

- ↑ 21.00 21.01 21.02 21.03 21.04 21.05 21.06 21.07 21.08 21.09 21.10 Dring DM (1980). "Contributions towards a rational arrangement of the Clathraceae". Kew Bulletin 35 (1): 1–96. doi:10.2307/4117008.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Arora D. (1986). Mushrooms Demystified: a Comprehensive Guide to the Fleshy Fungi. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. p. 765. ISBN 0-89815-169-4. https://archive.org/details/mushroomsdemysti00aror_0/page/765.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 The Macrofungus Flora of China's Guangdong Province (Chinese University Press). New York, New York: Columbia University Press. 1993. p. 542. ISBN 962-201-556-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=0cAered-vqYC&pg=PA542.

- ↑ "Pilz des Jahres 2011: Roter Gitterling (Clathrus ruber Pers.)" (in German). Deutsche Gesellschaft für Mykologie. http://dgfm-ev.de/index.php?id=664. "Diese Kreatur sieht eher aus wie ein Alien aus einem Sciencefictionhorrorfilm."

- ↑ "Clathrus ruber". California Fungi. MykoWeb. http://www.mykoweb.com/CAF/species/Clathrus_ruber.html.

- ↑ Jordan M. (2004). The Encyclopedia of Fungi of Britain and Europe. London, UK: Frances Lincoln. p. 366. ISBN 0-7112-2378-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=ULhwByKCyEwC&pg=PA366.

- ↑ Roman J. (2008). "Scarabaeus sacer Linnaeus, 1758 (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) visitando un hongo de la especie Clathrus ruber Micheli: Persoon (Clathraceae)" (in Spanish). Boletin de la SEA (Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa) 42: 348. ISSN 1134-6094.

- ↑ Stijve T. (1996). "Stinkhorns in abundance" (in Dutch). Coolia 39 (4): 229–36.

- ↑ Cooke MC (1862). A Plain and Easy Account of British Fungi; With Descriptions of the Esculent and Poisonous Species and a Tabular Arrangement of Orders and Genera. London, UK: Robert Hardwicke. p. 93. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/title/17210#151.

- ↑ "Ultrastructural studies of Clathraceae and Phallaceae (Gasteromycetes) spores". Mycologia 74 (1): 166–68. 1982. doi:10.2307/3792646. http://www.cybertruffle.org.uk/cyberliber/59350/0074/001/0166.htm.

- ↑ British Puffballs, Earthstars and Stinkhorns: An Account of the British Gasteroid Fungi. Kew, UK: Royal Botanic Gardens. 1995. p. 184. ISBN 0-947643-81-8.

- ↑ Dennis RWG (1954). "Some West Indian Gasteromycetes". Kew Bulletin 8 (3): 307–28. doi:10.2307/4115517.

- ↑ Kuo M. (August 2006). "Clathrus columnatus". MushroomExpert.com. http://www.mushroomexpert.com/clathrus_columnatus.html.

- ↑ Porcher FP (1854). "On the medicinal and toxicological properties of the cryptogamic plants of the United States". Transactions of the American Medical Association 7: 280. https://books.google.com/books?id=4sMCAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA280.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Ramsbottom J. (1953). Mushrooms & Toadstools: A Study of the Activities of Fungi. London, UK: Collins. pp. 187–88. https://books.google.com/books?id=cpA_AAAAYAAJ.

- ↑ Gasteromycetes: Morphological and Developmental Features, with Keys to the Orders, Families, and Genera. Eureka, California: Mad River Press. 1988. p. 76. ISBN 0-916422-74-7.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Kuo M. (August 2006). "Clathrus ruber". MushroomExpert.Com. http://www.mushroomexpert.com/clathrus_ruber.html.

- ↑ Eckblad F-E (1975). "Additions and corrections to the Gasteromycetes of the Canary Islands". Norwegian Journal of Botany 22 (4): 243–48.

- ↑ "Macrofungi of Aydin Province". Mycotaxon 99: 163–65. 2007. http://www.mu.edu.tr/departments/biyoloji/_private/ozgecmisler/hakanalli/macrofungi_aydin.pdf.

- ↑ "Macromycetes of Crimea, listed in the red data book of Ukraine" (in Ukrainian). Ukrayins'kyi Botanichnyi Zhurnal 60 (4): 438–46. 2003. ISSN 0372-4123.

- ↑ Dennis RWG (1955). "The status of Clathrus in England". Kew Bulletin 10 (1): 101–106. doi:10.2307/4113923.

- ↑ Miller GB (1988). "Clathrus in Cornwall". Mycologist 2 (1): 17. doi:10.1016/s0269-915x(88)80116-2.

- ↑ Roberts P. (1988). "Clathrus ruber: notes on two collections from Devon". Mycologist 2 (1): 14–16. doi:10.1016/S0269-915X(88)80115-0.

- ↑ Hope C. (1989). "Clathrus ruber on the Isle of Wight". Mycologist 3 (3): 111–12. doi:10.1016/S0269-915X(89)80036-9.

- ↑ "Catalog of Irish Fungi Part 1. Gasteromycetes". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 78 (1): 1–12. 1978.

- ↑ Burk WR (1979). "Clathrus ruber in California USA and worldwide distributional records". Mycotaxon 8 (2): 463–68. http://www.cybertruffle.org.uk/cyberliber/59575/0008/002/0463.htm.

- ↑ Cunningham GH (1931). "The Gasteromycetes of Australasia. XI. The Phallales, part II". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 56 (3): 182–200.

- ↑ Domínguez de Toledo L. (1995). "Gasteromycetes (Eumycota) del centro y oeste de la Argentina. II. Orden Phallales" (in Spanish). Darwiniana 33: 195–210.

- ↑ Minikata K. (1928). "Clathrus cancellatus TOURNEFORT 本邦二産ス" (in Japanese) (PDF). Botanical Magazine (Tokyo) 42 (496): 243–44. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jplantres1887/42/496/42_496_231/_pdf/-char/en.

- ↑ "Carotenes in the fungus Clathrus ruber (Gasteromycetes)". Mycologia 65 (1): 201–203. 1973. doi:10.2307/3757801. PMID 4686215. http://www.cybertruffle.org.uk/cyberliber/59350/0065/001/0201.htm.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clathrus ruber. |

- "Clathrus ruber: Champimaginatis" on YouTube (in French with English text)

- Bay Area Mycological Society Description and images

Wikidata ☰ Q579190 entry

|