Biology:GroES

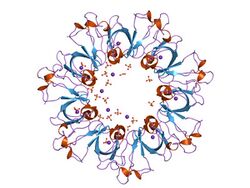

Generic protein structure example |

| Cpn10 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

gp31 co-chaperonin from bacteriophage t4 | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Cpn10 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00166 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0296 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR020818 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00576 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1lep / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Heat shock 10 kDa protein 1 (Hsp10), also known as chaperonin 10 (cpn10) or early-pregnancy factor (EPF), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the HSPE1 gene. The homolog in E. coli is GroES that is a chaperonin which usually works in conjunction with GroEL.[1]

Structure and function

GroES exists as a ring-shaped oligomer of between six and eight identical subunits, while the 60 kDa chaperonin (cpn60, or groEL in bacteria) forms a structure comprising 2 stacked rings, each ring containing 7 identical subunits.[2] These ring structures assemble by self-stimulation in the presence of Mg2+-ATP. The central cavity of the cylindrical cpn60 tetradecamer provides an isolated environment for protein folding whilst cpn-10 binds to cpn-60 and synchronizes the release of the folded protein in an Mg2+-ATP dependent manner.[3] The binding of cpn10 to cpn60 inhibits the weak ATPase activity of cpn60.

Escherichia coli GroES has also been shown to bind ATP cooperatively, and with an affinity comparable to that of GroEL.[4] Each GroEL subunit contains three structurally distinct domains: an apical, an intermediate and an equatorial domain. The apical domain contains the binding sites for both GroES and the unfolded protein substrate. The equatorial domain contains the ATP-binding site and most of the oligomeric contacts. The intermediate domain links the apical and equatorial domains and transfers allosteric information between them. The GroEL oligomer is a tetradecamer, cylindrically shaped, that is organised in two heptameric rings stacked back to back. Each GroEL ring contains a central cavity, known as the `Anfinsen cage', that provides an isolated environment for protein folding. The identical 10 kDa subunits of GroES form a dome-like heptameric oligomer in solution. ATP binding to GroES may be important in charging the seven subunits of the interacting GroEL ring with ATP, to facilitate cooperative ATP binding and hydrolysis for substrate protein release.

Interactions

GroES has been shown to interact with GroEL.[5][6]

Detection

Early pregnancy factor is tested for rosette inhibition assay. EPF is present in the maternal serum (blood plasma) shortly after fertilization; EPF is also present in cervical mucus [7] and in amniotic fluid.[8]

EPF may be detected in sheep within 72 hours of mating,[9] in mice within 24 hours of mating,[10] and in samples from media surrounding human embryos fertilized in vitro within 48 hours of fertilization[11] (although another study failed to duplicate this finding for in vitro embryos).[12] EPF has been detected as soon as within six hours of mating.[13]

Because the rosette inhibition assay for EPF is indirect, substances that have similar effects may confound the test. Pig semen, like EPF, has been shown to inhibit rosette formation – the rosette inhibition test was positive for one day in sows mated with a vasectomized boar, but not in sows similarly stimulated without semen exposure.[14] A number of studies in the years after the discovery of EPF were unable to reproduce the consistent detection of EPF in post-conception females, and the validity of the discovery experiments was questioned.[15] However, progress in characterization of EPF has been made and its existence is well-accepted in the scientific community.[16][17]

Origin

Early embryos are not believed to directly produce EPF. Rather, embryos are believed to produce some other chemical that induces the maternal system to create EPF.[18][19][20][21][22] After implantation, EPF may be produced by the conceptus directly.[12]

EPF is an immunosuppressant. Along with other substances associated with early embryos, EPF is believed to play a role in preventing the immune system of the pregnant female from attacking the embryo.[13][23] Injecting anti-EPF antibodies into mice after mating significantly [quantify] reduced the number of successful pregnancies and number of pups;[24][25] no effect on growth was seen when mice embryos were cultured in media containing anti-EPF antibodies.[26] While some actions of EPF are the same in all mammals (namely rosette inhibition), other immunosuppressant mechanism vary between species.[27]

In mice, EPF levels are high in early pregnancy, but on day 15 decline to levels found in non-pregnant mice.[28] In humans, EPF levels are high for about the first twenty weeks, then decline, becoming undetectable within eight weeks of delivery.[29][30]

Clinical utility

Pregnancy testing

It has been suggested that EPF could be used as a marker for a very early pregnancy test, and as a way to monitor the viability of ongoing pregnancies in livestock.[9] Interest in EPF for this purpose has continued,[31] although current test methods have not proved sufficiently accurate for the requirements of livestock management.[32][33][34][35]

In humans, modern pregnancy tests detect human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). hCG is not present until after implantation, which occurs six to twelve days after fertilization.[36] In contrast, EPF is present within hours of fertilization. While several other pre-implantation signals have been identified, EPF is believed to be the earliest possible marker of pregnancy.[10][37] The accuracy of EPF as a pregnancy test in humans has been found to be high by several studies.[38][39][40][41]

Birth control research

EPF may also be used to determine whether pregnancy prevention mechanism of birth control methods act before or after fertilization. A 1982 study evaluating EPF levels in women with IUDs concluded that post-fertilization mechanisms contribute significantly[quantify] to the effectiveness of these devices.[42] However, more recent evidence, such as tubal flushing studies indicates that IUDs work by inhibiting fertilization, acting earlier in the reproductive process than previously thought.[43]

For groups that define pregnancy as beginning with fertilization, birth control methods that have postfertilization mechanisms are regarded as abortifacient. There is currently contention over whether hormonal contraception methods have post-fertilization methods, specifically the most popular hormonal method: the combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP). The group Pharmacists for Life has called for a large-scale clinical trial to evaluate EPF in women taking COCPs; this would be the most conclusive evidence available to determine whether COCPs have postfertilization mechanisms.[44]

Infertility and early pregnancy loss

EPF is useful when investigating embryo loss prior to implantation. One study in healthy human women seeking pregnancy detected fourteen pregnancies with EPF. Of these, six were lost within ten days of ovulation (43% rate of early conceptus loss).[45]

Use of EPF has been proposed to distinguish infertility caused by failure to conceive versus infertility caused by failure to implant.[46] EPF has also been proposed as a marker of viable pregnancy, more useful in distinguishing ectopic or other nonviable pregnancies than other chemical markers such as hCG and progesterone.[47][48][49][50]

As a tumour marker

Although almost exclusively associated with pregnancy, EPF-like activity has also been detected in tumors of germ cell origin[51][52] and in other types of tumors.[53] Its utility as a tumour marker, to evaluate the success of surgical treatment, has been suggested.[54]

References

- ↑ "Entrez Gene: HSPE1 heat shock 10kDa protein 1 (chaperonin 10)". https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=gene&Cmd=ShowDetailView&TermToSearch=3336.

- ↑ "Homologous plant and bacterial proteins chaperone oligomeric protein assembly". Nature 333 (6171): 330–4. May 1988. doi:10.1038/333330a0. PMID 2897629. Bibcode: 1988Natur.333..330H.

- ↑ "Cloning, sequencing, mapping, and transcriptional analysis of the groESL operon from Bacillus subtilis". J. Bacteriol. 174 (12): 3993–9. June 1992. doi:10.1128/jb.174.12.3993-3999.1992. PMID 1350777.

- ↑ "Identification of nucleotide-binding regions in the chaperonin proteins GroEL and GroES". Nature 366 (6452): 279–82. November 1993. doi:10.1038/366279a0. PMID 7901771. Bibcode: 1993Natur.366..279M.

- ↑ "Presence of a pre-apoptotic complex of pro-caspase-3, Hsp60 and Hsp10 in the mitochondrial fraction of jurkat cells". EMBO J. 18 (8): 2040–8. April 1999. doi:10.1093/emboj/18.8.2040. PMID 10205158.

- ↑ "Chaperonin GroESL mediates the protein folding of human liver mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase in Escherichia coli". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 298 (2): 216–24. October 2002. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02423-3. PMID 12387818.

- ↑ "Early pregnancy factor in cervical mucus of pregnant women". American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 51 (2): 102–5. Feb 2004. doi:10.1046/j.8755-8920.2003.00136.x. PMID 14748834.

- ↑ "Detection of early pregnancy factor-like activity in human amniotic fluid". American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 22 (1–2): 9–11. 1990. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1990.tb01025.x. PMID 2346595.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "A test for early pregnancy in sheep". Research in Veterinary Science 26 (2): 261–2. Mar 1979. doi:10.1016/S0034-5288(18)32933-3. PMID 262615.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Ovum factor: a first signal of pregnancy?". American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2 (2): 97–101. Apr 1982. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1982.tb00093.x. PMID 7102890.

- ↑ "Detection of an immunosuppressive factor in human preimplantation embryo cultures". The Medical Journal of Australia 1 (2): 78–9. Jan 1981. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1981.tb135326.x. PMID 7231254.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Human embryonic origin early pregnancy factor before and after implantation". American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 22 (3–4): 105–8. 1990. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1990.tb00651.x. PMID 2375830.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "The immunological approach to pregnancy diagnosis: a review". The Veterinary Record 106 (12): 268–70. Mar 1980. doi:10.1136/vr.106.12.268. PMID 6966439.

- ↑ "Detection of activity similar to that of early pregnancy factor after mating sows with a vasectomized boar". Journal of Reproduction and Fertility 74 (1): 39–46. May 1985. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0740039. PMID 4020773.

- ↑ "Early pregnancy factor". Biological Research in Pregnancy and Perinatology 8 (2 2D Half): 53–6. 1987. PMID 3322417.

- ↑ "Isolation from human placental extracts of a preparation possessing 'early pregnancy factor' activity and identification of the polypeptide components". Human Reproduction 6 (3): 450–7. Mar 1991. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137357. PMID 1955557.

- ↑ "Identification of early pregnancy factor as chaperonin 10: implications for understanding its role". Reviews of Reproduction 1 (1): 28–32. Jan 1996. doi:10.1530/ror.0.0010028. PMID 9414435.

- ↑ "Platelet-activating factor induces the expression of early pregnancy factor activity in female mice". Journal of Reproduction and Fertility 78 (2): 549–55. Nov 1986. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0780549. PMID 3806515.

- ↑ "An evaluation of peripheral blood platelet enumeration as a monitor of fertilization and early pregnancy". Fertility and Sterility 47 (5): 848–54. May 1987. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)59177-8. PMID 3569561.

- ↑ "Platelet activating factor-induced early pregnancy factor activity from the perfused rabbit ovary and oviduct". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 159 (6): 1580–4. Dec 1988. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(88)90598-4. PMID 3207134.

- ↑ "Identification of a putative inhibitor of early pregnancy factor in mice". Journal of Reproduction and Fertility 91 (1): 239–48. Jan 1991. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0910239. PMID 1995852.

- ↑ "Relationship between early pregnancy factor, mouse embryo-conditioned medium and platelet-activating factor". Journal of Reproduction and Fertility 93 (2): 355–65. Nov 1991. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0930355. PMID 1787455.

- ↑ "Purified human early pregnancy factor from preimplantation embryo possesses immunosuppresive properties". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 160 (4): 954–60. Apr 1989. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(89)90316-5. PMID 2712125.

- ↑ "[Significance of early pregnancy factor (EPF) on reproductive immunology]". Nihon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi 39 (2): 189–94. Feb 1987. PMID 2950188.

- ↑ "Passive immunization of pregnant mice against early pregnancy factor causes loss of embryonic viability". Journal of Reproduction and Fertility 87 (2): 495–502. Nov 1989. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0870495. PMID 2600905.

- ↑ "Antibodies to early pregnancy factor retard embryonic development in mice in vivo". Journal of Reproduction and Fertility 92 (2): 443–51. Jul 1991. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0920443. PMID 1886100.

- ↑ "Identification of two suppressor factors induced by early pregnancy factor". Clinical and Experimental Immunology 73 (2): 219–25. Aug 1988. PMID 3180511.

- ↑ "Detection of early pregnancy factor in superovulated mice". Nihon Juigaku Zasshi. The Japanese Journal of Veterinary Science 51 (5): 879–85. Oct 1989. doi:10.1292/jvms1939.51.879. PMID 2607739.

- ↑ "Detection of early pregnancy factor in human sera". American Journal of Reproductive Immunology and Microbiology 13 (1): 15–8. Jan 1987. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1987.tb00082.x. PMID 2436493.

- ↑ "Detection of early pregnancy factor in fetal sera". American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 23 (3): 69–72. Jul 1990. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1990.tb00674.x. PMID 2257053.

- ↑ "Monitoring bovine embryo viability with early pregnancy factor". The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 55 (2): 271–4. Apr 1993. doi:10.1292/jvms.55.271. PMID 8513008.

- ↑ "[Evaluation of the method for early pregnancy factor detection (EPF) in swine. Significance in early pregnancy diagnosis]". Acta Physiologica, Pharmacologica et Therapeutica Latinoamericana 42 (1): 43–50. 1992. PMID 1294272.

- ↑ "Detection of early pregnancy in domestic ruminants". Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. Supplement 34: 261–71. 1987. PMID 3305923.

- ↑ "Evaluation of the early conception factor (ECF) test for the detection of nonpregnancy in dairy cattle". Theriogenology 56 (4): 637–47. Sep 2001. doi:10.1016/S0093-691X(01)00595-7. PMID 11572444.

- ↑ "Assessment of a commercially available early conception factor (ECF) test for determining pregnancy status of dairy cattle". Journal of Dairy Science 84 (8): 1884–9. Aug 2001. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(01)74629-2. PMID 11518314.

- ↑ "Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy". The New England Journal of Medicine 340 (23): 1796–9. Jun 1999. doi:10.1056/NEJM199906103402304. PMID 10362823.

- ↑ "[Early embryonal signals]". Zentralblatt für Gynäkologie 111 (10): 629–33. 1989. PMID 2665388.

- ↑ "Validation of the rosette inhibition test for the detection of early pregnancy in women". Fertility and Sterility 37 (6): 779–85. Jun 1982. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)46338-7. PMID 6177559.

- ↑ "[Detection of early pregnancy factor in the sera of conceived women before nidation]". Nihon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi 36 (3): 391–6. Mar 1984. PMID 6715922.

- ↑ "Detection of early pregnancy factor (EPF) in pregnant and nonpregnant subjects with the rosette inhibition test". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 246 (3): 181–7. 1989. doi:10.1007/BF00934079. PMID 2619332.

- ↑ "A study of early pregnancy factor activity in preimplantation". American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 37 (5): 359–64. May 1997. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1997.tb00244.x. PMID 9196793.

- ↑ "Early pregnancy factor as a monitor for fertilization in women wearing intrauterine devices". Fertility and Sterility 37 (2): 201–4. Feb 1982. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)46039-5. PMID 6174375.

- ↑ Grimes, David (2007). "Intrauterine Devices (IUDs)". in Hatcher, Robert A.. Contraceptive Technology (19th rev. ed.). New York: Ardent Media. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-9664902-0-6. https://archive.org/details/contraceptivetec00hatc/page/120.

- ↑ Lloyd J DuPlantis, Jr (2001). Early Pregnancy Factor. Pharmacists for Life, Intl. http://www.lifeissues.net/writers/dup/dup_01earlypregfacts.html. Retrieved 2007-01-01.

- ↑ "Fertilization and early pregnancy loss in healthy women attempting conception". Clinical Reproduction and Fertility 1 (3): 177–84. Sep 1982. PMID 6196101.

- ↑ "[Early abortion rate in sterility patients: early pregnancy factor as a parameter]". Zentralblatt für Gynäkologie 110 (9): 555–61. 1988. PMID 3407357.

- ↑ "[Significance of the detection of early pregnancy factor for monitoring normal and disordered early pregnancy]". Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde 48 (12): 854–8. Dec 1988. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1026640. PMID 2466731.

- ↑ "The early pregnancy factor (EPF) in pregnancies of women with habitual abortions". Early Human Development 26 (2): 83–92. 1991. doi:10.1016/0378-3782(91)90012-R. PMID 1720719.

- ↑ "A study of early pregnancy factor activity in the sera of patients with unexplained spontaneous abortion". American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 29 (2): 77–81. Mar 1993. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1993.tb00569.x. PMID 8329108.

- ↑ "Early pregnancy factor as a marker for assessing embryonic viability in threatened and missed abortions". Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 37 (2): 73–6. 1994. doi:10.1159/000292528. PMID 8150373.

- ↑ "Detection of an early pregnancy factor-like substance in sera of patients with testicular germ cell tumors". American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 3 (2): 97–100. Mar 1983. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1983.tb00223.x. PMID 6859385.

- ↑ "Detection of early pregnancy factor-like activity in women with gestational trophoblastic tumors". American Journal of Reproductive Immunology and Microbiology 14 (3): 67–9. Jul 1987. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1987.tb00122.x. PMID 2823620.

- ↑ "Monoclonal antibodies to early pregnancy factor perturb tumour cell growth". Clinical and Experimental Immunology 80 (1): 100–8. Apr 1990. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb06448.x. PMID 2323098.

- ↑ "[Case observations on the significance of early pregnancy factor as a tumor marker]". Zentralblatt für Gynäkologie 115 (3): 125–8. 1993. PMID 7682025.

Further reading

- "Heat shock protein 10 and signal transduction: a "capsula eburnea" of carcinogenesis?". Cell Stress & Chaperones 11 (4): 287–94. 2006. doi:10.1379/CSC-200.1. PMID 17278877.

- "Expression in Escherichia coli, purification and functional activity of recombinant human chaperonin 10". FEBS Lett. 361 (2–3): 211–4. 1995. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(95)00184-B. PMID 7698325.

- "The purification of early-pregnancy factor to homogeneity from human platelets and identification as chaperonin 10". Eur. J. Biochem. 222 (2): 551–60. 1994. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18897.x. PMID 7912672.

- "Identification and cloning of human chaperonin 10 homologue". Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1218 (3): 478–80. 1994. doi:10.1016/0167-4781(94)90211-9. PMID 7914093.

- "Isolation, sequence analysis and characterization of a cDNA encoding human chaperonin 10". Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1219 (1): 189–90. 1994. doi:10.1016/0167-4781(94)90268-2. PMID 7916212.

- "Presence of a pre-apoptotic complex of pro-caspase-3, Hsp60 and Hsp10 in the mitochondrial fraction of jurkat cells". EMBO J. 18 (8): 2040–8. 1999. doi:10.1093/emboj/18.8.2040. PMID 10205158.

- "Mapping and characterization of the eukaryotic early pregnancy factor/chaperonin 10 gene family". Somat. Cell Mol. Genet. 24 (6): 315–26. 1998. doi:10.1023/A:1024488422990. PMID 10763410.

- "The importance of a mobile loop in regulating chaperonin/ co-chaperonin interaction: humans versus Escherichia coli". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (7): 4981–7. 2001. doi:10.1074/jbc.M008628200. PMID 11050098.

- "The murine chaperonin 10 gene family contains an intronless, putative gene for early pregnancy factor, Cpn10-rs1". Mamm. Genome 12 (2): 133–40. 2001. doi:10.1007/s003350010250. PMID 11210183.

- "Functional interactions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase with human and yeast HSP60". J. Virol. 75 (23): 11344–53. 2001. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.23.11344-11353.2001. PMID 11689615.

- "Hereditary spastic paraplegia SPG13 is associated with a mutation in the gene encoding the mitochondrial chaperonin Hsp60". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70 (5): 1328–32. 2002. doi:10.1086/339935. PMID 11898127.

- "Low stability for monomeric human chaperonin protein 10: interprotein interactions contribute majority of oligomer stability". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 405 (2): 280–2. 2002. doi:10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00406-X. PMID 12220543.

- "Chaperonin GroESL mediates the protein folding of human liver mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase in Escherichia coli". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 298 (2): 216–24. 2002. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02423-3. PMID 12387818.

- "Genomic structure of the human mitochondrial chaperonin genes: HSP60 and HSP10 are localised head to head on chromosome 2 separated by a bidirectional promoter". Hum. Genet. 112 (1): 71–7. 2003. doi:10.1007/s00439-002-0837-9. PMID 12483302.

- "Type I collagen synthesis by human osteoblasts in response to placental lactogen and chaperonin 10, a homolog of early-pregnancy factor". In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 38 (9): 518–22. 2002. doi:10.1290/1071-2690(2002)038<0518:TICSBH>2.0.CO;2. PMID 12703979.

- "Ten kilodalton heat shock protein (HSP10) is overexpressed during carcinogenesis of large bowel and uterine exocervix". Cancer Lett. 196 (1): 35–41. 2003. doi:10.1016/S0304-3835(03)00212-X. PMID 12860287. https://iris.unipa.it/bitstream/10447/191095/1/OP%2012.%20Cappello%20et%20al%252c%20Cancer%20Lett%202003.pdf.

- "Hsp10 and Hsp60 modulate Bcl-2 family and mitochondria apoptosis signaling induced by doxorubicin in cardiac muscle cells". J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 35 (9): 1135–43. 2003. doi:10.1016/S0022-2828(03)00229-3. PMID 12967636.

- "Hsp10 and Hsp60 suppress ubiquitination of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and augment insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor signaling in cardiac muscle: implications on decreased myocardial protection in diabetic cardiomyopathy". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (46): 45492–8. 2003. doi:10.1074/jbc.M304498200. PMID 12970367.

- "Probing the interface in a human co-chaperonin heptamer: residues disrupting oligomeric unfolded state identified". BMC Biochem. 4: 14. 2003. doi:10.1186/1471-2091-4-14. PMID 14525625.

External links

- GroES+Protein at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- 3D macromolecular structures of GroES in EMDB

|