Medicine:Gonorrhea

| Gonorrhea | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Gonorrhoea, gonococcal infection, gonococcal urethritis, the clap |

| |

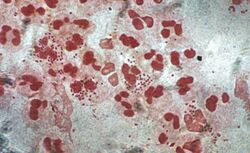

| Gonococcal lesion on the skin | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | None, burning with urination, vaginal discharge, discharge from the penis, pelvic pain, testicular pain[1] |

| Complications | Pelvic inflammatory disease, inflammation of the epididymis, septic arthritis, endocarditis[1][2] |

| Causes | Neisseria gonorrhoeae typically sexually transmitted[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Testing the urine, urethra in males, or cervix in females[1] |

| Prevention | Condoms, having sex with only one person who is uninfected, not having sex[1][3] |

| Treatment | Ceftriaxone by injection and azithromycin by mouth[4][5] |

| Frequency | 0.8% (women), 0.6% (men)[6] |

Gonorrhoea or gonorrhea, colloquially known as the clap, is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae.[1] Infection may involve the genitals, mouth, or rectum.[7] Infected men may experience pain or burning with urination, discharge from the penis, or testicular pain.[1] Infected women may experience burning with urination, vaginal discharge, vaginal bleeding between periods, or pelvic pain.[1] Complications in women include pelvic inflammatory disease and in men include inflammation of the epididymis.[1] Many of those infected, however, have no symptoms.[1] If untreated, gonorrhea can spread to joints or heart valves.[1][2]

Gonorrhea is spread through sexual contact with an infected person.[1] This includes oral, anal, and vaginal sex.[1] It can also spread from a mother to a child during birth.[1] Diagnosis is by testing the urine, urethra in males, or cervix in females.[1] Testing all women who are sexually active and less than 25 years of age each year as well as those with new sexual partners is recommended;[3] the same recommendation applies in men who have sex with men (MSM).[3]

Gonorrhea can be prevented with the use of condoms, having sex with only one person who is uninfected, and by not having sex.[1][3] Treatment is usually with ceftriaxone by injection and azithromycin by mouth.[4][5] Resistance has developed to many previously used antibiotics and higher doses of ceftriaxone are occasionally required.[4][5] Retesting is recommended three months after treatment.[3] Sexual partners from the last two months should also be treated.[1]

Gonorrhea affects about 0.8% of women and 0.6% of men.[6] An estimated 33 to 106 million new cases occur each year, out of the 498 million new cases of curable STI – which also includes syphilis, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis.[8][9] Infections in women most commonly occur when they are young adults.[3] In 2015, it caused about 700 deaths.[10] Descriptions of the disease date back to before the Common Era within the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament (Leviticus 15:2-3).[2] The current name was first used by the Greek physician Galen before AD 200 who referred to it as "an unwanted discharge of semen".[2]

Signs and symptoms

Gonorrhea infections of mucosal membranes can cause swelling, itching, pain, and the formation of pus.[11] The time from exposure to symptoms is usually between two and 14 days, with most symptoms appearing between four and six days after infection, if they appear at all. Both men and women with infections of the throat may experience a sore throat, though such infection does not produce symptoms in 90% of cases.[12][13] Other symptoms may include swollen lymph nodes around the neck.[11] Either sex can become infected in the eyes or rectum if these tissues are exposed to the bacterium,[14] which can lead to pain with bowel movements, rectal discharge, or constipation.[15]

Women

Half of women with gonorrhea are asymptomatic but the other half experience vaginal discharge, lower abdominal pain, or pain with sexual intercourse associated with inflammation of the uterine cervix.[16][17][18] Common medical complications of untreated gonorrhea in women include pelvic inflammatory disease which can cause scars to the fallopian tubes and result in later ectopic pregnancy among those women who become pregnant.[19]

Men

Most infected men with symptoms have inflammation of the penile urethra associated with a burning sensation during urination and discharge from the penis.[17] In men, discharge with or without burning occurs in half of all cases and is the most common symptom of the infection.[20] This pain is caused by a narrowing and stiffening of the urethral lumen.[21] The most common medical complication of gonorrhea in men is inflammation of the epididymis.[19] Gonorrhea is also associated with increased risk of prostate cancer.[22]

Infants

If not treated, gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum will develop in 28% of infants born to women with gonorrhea.[23]

Spread

If left untreated, gonorrhea can spread from the original site of infection and infect and damage the joints, skin, and other organs. Indications of this can include fever, skin rashes, sores, and joint pain and swelling.[19] In advanced cases, gonorrhea may cause a general feeling of tiredness similar to other infections.[24][20] It is also possible for an individual to have an allergic reaction to the bacteria, in which case any appearing symptoms will be greatly intensified.[20] Very rarely it may settle in the heart, causing endocarditis, or in the spinal column, causing meningitis. Both are more likely among individuals with suppressed immune systems, however.[13]

Cause

Gonorrhea is caused by the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae.[17] Previous infection does not confer immunity – a person who has been infected can become infected again by exposure to someone who is infected. Infected persons may be able to infect others repeatedly without having any signs or symptoms of their own.[25]

Spread

The infection is usually spread from one person to another through vaginal, oral, or anal sex.[17][26] Men have a 20% risk of getting the infection from a single act of vaginal intercourse with an infected woman. The risk for men who have sex with men (MSM) is higher.[27] Insertive MSM may get a penile infection from anal intercourse, while receptive MSM may get anorectal gonorrhea.[28] Women have a 60–80% risk of getting the infection from a single act of vaginal intercourse with an infected man.[29]

A mother may transmit gonorrhea to her newborn during childbirth; when affecting the infant's eyes, it is referred to as ophthalmia neonatorum.[17] It may be able to spread through the objects contaminated with body fluid from an infected person.[30] The bacteria typically does not survive long outside the body, typically dying within minutes to hours.[31]

Risk factors

It is discovered that sexually active women younger than 25 and men who have sex with men are at increased risk of getting gonorrhea.[32]

Other risk factors include:

- Having a new sex partner

- Having a sex partner who has other partners

- Having more than one sex partner

- Having had gonorrhea or another sexually transmitted infection[33]

Complications

Untreated gonorrhea can lead to major complications, such as:

- Infertility in women. Gonorrhea can spread into the uterus and fallopian tubes, causing pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). PID can result in scarring of the tubes, greater risk of pregnancy complications and infertility, and can be fatal, particularly in the immunocompromised.[citation needed] PID requires immediate treatment.

- Infertility in men. Gonorrhea can cause a small, coiled tube in the rear portion of the testicles where the sperm ducts are located (epididymis) to become inflamed (epididymitis). Untreated epididymitis can lead to infertility.

- Infection that spreads to the joints and other areas of the body. The bacterium that causes gonorrhea can spread through the bloodstream and infect other parts of the body, including the joints. Fever, rash, skin sores, joint pain, swelling and stiffness are possible results.

- Increased risk of HIV/AIDS. Having gonorrhea increases the susceptibility to infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus that leads to AIDS. People who have both gonorrhea and HIV (untreated by anti-retroviral therapy) are able to pass both diseases more readily to their partners.

- Complications in babies. Babies who contract gonorrhea from their mothers during birth can develop blindness, sores on the scalp and infections.[24][25]

Diagnosis

Traditionally, gonorrhea was diagnosed with Gram stain and culture; however, newer polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based testing methods are becoming more common.[18][34] If initial treatment fails, a culture should be done to determine the sensitivity of the bacteria to antibiotics.[35]

Tests that use PCR (aka nucleic acid amplification) to identify genes unique to N. gonorrhoeae are recommended for screening and diagnosis of gonorrhea infection. These PCR-based tests require a sample of urine, urethral swabs, or cervical/vaginal swabs. Culture (growing colonies of bacteria in order to isolate and identify them) and Gram-stain (staining of bacterial cell walls to reveal morphology) can also be used to detect the presence of N. gonorrhoeae in all specimen types except urine.[36][37] Studies of the swab sample method for gonorrhea infections have not shown any difference in the number of patients treated, whether the sample was collected at home or in the clinic. The implications for number of patients cured, reinfection rates, partner management, and safety are unknown.[38]

If Gram-negative, oxidase-positive diplococci are visualized on direct Gram stain of urethral pus (male genital infection), no further testing is needed to establish the diagnosis of gonorrhea infection.[39][40] However, direct Gram stain of cervical swabs is not useful because the N. gonorrhoeae organisms are less concentrated in these samples. The chance of a false positive test is also higher for a cervical swab, as Gram-negative diplococci native to the normal vaginal flora cannot be distinguished from N. gonorrhoeae in that context. Thus, cervical swabs must be cultured under the conditions described above. If oxidase positive, Gram-negative diplococci are isolated from a culture of a cervical/vaginal swab specimen, then the diagnosis is made. Culture is especially useful for diagnosis of infections of the throat, rectum, eyes, blood, or joints—areas where PCR-based tests are not well established in all labs.[40][41] Culture is also useful for antimicrobial sensitivity testing, analyzing treatment failure, and epidemiological purposes (outbreaks, surveillance).[40]

In patients who may have disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI), all possible mucosal sites should be cultured (e.g., pharynx, cervix, urethra, rectum).[41] Three sets of blood cultures should also be obtained.[42] Synovial fluid should be collected in cases of septic arthritis.[41]

All people testing positive for gonorrhea should be tested for other sexually transmitted infections such as chlamydia, syphilis, and human immunodeficiency virus.[35] Studies have found co-infection with chlamydia ranging from 46 to 54% in young people with gonorrhea.[43][44] Among persons in the United States between 14 and 39 years of age, 46% of people with gonorrheal infection also have chlamydial infection.[45] For this reason, gonorrhea and chlamydia testing are often combined.[36][46][47] People diagnosed with gonorrhea infection have a fivefold increase risk of HIV transmission.[48] Additionally, infected persons who are HIV positive are more likely to shed and transmit HIV to uninfected partners during an episode of gonorrhea.[49]

Screening

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for gonorrhea in women at increased risk of infection, which includes all sexually active women younger than 25 years. Extragenital gonorrhea and chlamydia are highest in men who have sex with men (MSM).[50] Additionally, the USPSTF also recommends routine screening in people who have previously tested positive for gonorrhea or have multiple sexual partners and individuals who use condoms inconsistently, provide sexual favors for money, or have sex while under the influence of alcohol or drugs.[16]

Screening for gonorrhea in women who are (or intend to become) pregnant, and who are found to be at high risk for sexually transmitted infections, is recommended as part of prenatal care in the United States.[51]

Prevention

As with most sexually transmitted infections, the risk of infection can be reduced significantly by the correct use of condoms, not having sex, or can be removed almost entirely by limiting sexual activities to a mutually monogamous relationship with an uninfected person.[52][53]

Those previously infected are encouraged to return for follow up care to make sure that the infection has been eliminated. In addition to the use of phone contact, the use of email and text messaging have been found to improve the re-testing for infection.[54]

Newborn babies coming through the birth canal are given erythromycin ointment in the eyes to prevent blindness from infection. The underlying gonorrhea should be treated; if this is done then usually a good prognosis will follow.[55]

Treatment

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are used to treat gonorrhea infections. As of 2016, both ceftriaxone by injection and azithromycin by mouth are most effective.[4][56][57][58] However, due to increasing rates of antibiotic resistance, local susceptibility patterns must be taken into account when deciding on treatment.[35][59] Ertapenem is a potential effective alternative treatment for ceftriaxone-resistant gonorrhea.[60][61]

Adults may have eyes infected with gonorrhoea and require proper personal hygiene and medications.[55] Addition of topical antibiotics have not been shown to improve cure rates compared to oral antibiotics alone in treatment of eye infected gonorrhea.[62] For newborns, erythromycin ointment is recommended as a preventative measure for gonococcal infant conjunctivitis.[63]

Infections of the throat can be especially problematic, as antibiotics have difficulty becoming sufficiently concentrated there to destroy the bacteria. This is amplified by the fact that pharyngeal gonorrhoea is mostly asymptomatic, and gonococci and commensal Neisseria species can coexist for long time periods in the pharynx and share anti-microbial resistance genes. Accordingly, an enhanced focus on early detection (i.e., screening of high-risk populations, such as men who have sex with men, PCR testing should be considered) and appropriate treatment of pharyngeal gonorrhoea is important.[4]

Sexual partners

It is recommended that sexual partners be tested and potentially treated.[35] One option for treating sexual partners of people infected is patient-delivered partner therapy (PDPT), which involves providing prescriptions or medications to the person to take to his/her partner without the health care provider's first examining him/her.[64]

The United States' Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) currently recommend that individuals who have been diagnosed and treated for gonorrhea avoid sexual contact with others until at least one week past the final day of treatment in order to prevent the spread of the bacterium.[65]

Antibiotic resistance

Many antibiotics that were once effective including penicillin, tetracycline, and fluoroquinolones are no longer recommended because of high rates of resistance.[35] Resistance to cefixime has reached a level such that it is no longer recommended as a first-line agent in the United States, and if it is used a person should be tested again after a week to determine whether the infection still persists.[56] Public health officials are concerned that an emerging pattern of resistance may predict a global epidemic.[66][67] In 2016, the WHO published new guidelines for treatment, stating "There is an urgent need to update treatment recommendations for gonococcal infections to respond to changing antimicrobial resistance (AMR) patterns of N. gonorrhoeae. High-level resistance to previously recommended quinolones is widespread and decreased susceptibility to the extended-spectrum (third-generation) cephalosporins, another recommended first-line treatment in the 2003 guidelines, is increasing and several countries have reported treatment failures."[68]

Prognosis

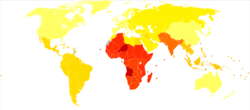

| no data <13 13–26 26–39 39–52 52–65 65–78 | 78–91 91–104 104–117 117–130 130–143 >143 |

Gonorrhea if left untreated may last for weeks or months with higher risks of complications.[17] One of the complications of gonorrhea is systemic dissemination resulting in skin pustules or petechia, septic arthritis, meningitis, or endocarditis.[17] This occurs in between 0.6 and 3% of infected women and 0.4 and 0.7% of infected men.[17]

In men, inflammation of the epididymis, prostate gland, and urethra can result from untreated gonorrhea.[69] In women, the most common result of untreated gonorrhea is pelvic inflammatory disease. Other complications include inflammation of the tissue surrounding the liver,[69] a rare complication associated with Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome; septic arthritis in the fingers, wrists, toes, and ankles; septic abortion; chorioamnionitis during pregnancy; neonatal or adult blindness from conjunctivitis; and infertility. Men who have had a gonorrhea infection have an increased risk of getting prostate cancer.[22]

Epidemiology

About 88 million cases of gonorrhea occur each year, out of the 448 million new cases of curable STI each year – that also includes syphilis, chlamydia and trichomoniasis.[9] The prevalence was highest in the African region, the Americas, and Western Pacific, and lowest in Europe.[70] In 2013, it caused about 3,200 deaths, up from 2,300 in 1990.[71]

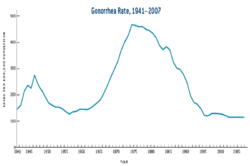

In the United Kingdom, 196 per 100,000 males 20 to 24 years old and 133 per 100,000 females 16 to 19 years old were diagnosed in 2005.[17] In 2013, the CDC estimated that more than 820,000 people in the United States get a new gonorrheal infection each year. Fewer than half of these infections are reported to CDC. In 2011, 321,849 cases of gonorrhea were reported to the CDC. After the implementation of a national gonorrhea control program in the mid-1970s, the national gonorrhea rate declined from 1975 to 1997. After a small increase in 1998, the gonorrhea rate has decreased slightly since 1999. In 2004, the rate of reported gonorrheal infections was 113. 5 per 100,000 persons.[72]

In the US, it is the second-most-common bacterial sexually transmitted infections; chlamydia remains first.[73][74] According to the CDC African Americans are most affected by gonorrhea, accounting for 69% of all gonorrhea cases in 2010.[75]

The World Health Organization warned in 2017 of the spread of untreatable strains of gonorrhea, following analysis of at least three cases in Japan, France and Spain, which survived all antibiotic treatment.[76]

History

Some scholars translate the biblical terms zav (for a male) and zavah (for a female) as gonorrhea.[77]

It has been suggested[by whom?] that mercury was used as a treatment for gonorrhea.[when?] Surgeons' tools on board the recovered English warship the Mary Rose included a syringe that, according to some, was used to inject the mercury via the urinary meatus into crewmen with gonorrhea. The name "the clap", in reference to the disease, is recorded as early as the sixteenth century, referring to a medieval red-light district in Paris, Les Clapiers. Translating to "The rabbit holes", it was so named for the small huts in which prostitutes worked.[78][59]

In 1854, Dr. Wilhelm Gollmann addressed gonorrhea in his book, Homeopathic Guide to all Diseases Urinary and Sexual Organs. He noted that the disease was common in prostitutes and homosexuals in large cities. Gollmann recommended the following as cures: aconite to cure "shooting pains with soreness and inflammation"; mercury "for stitching pain with purulent discharge"; nux vomica and sulphur "when the symptoms are complicated with hemorrhoids and stricture of the rectum. Other remedies include argentum, aurum (gold), belladonna, calcarea, ignatia, phosphorus, and sepia".[28]

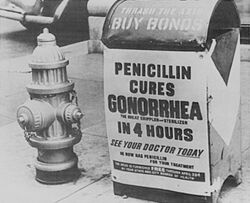

Silver nitrate was one of the widely used drugs in the 19th century. However, it became replaced by Protargol. Arthur Eichengrün invented this type of colloidal silver, which was marketed by Bayer from 1897 onward. The silver-based treatment was used until the first antibiotics came into use in the 1940s.[79][80]

The exact time of onset of gonorrhea as prevalent disease or epidemic cannot be accurately determined from the historical record. One of the first reliable notations occurs in the Acts of the (English) Parliament. In 1161, this body passed a law to reduce the spread of "... the perilous infirmity of burning".[81] The symptoms described are consistent with, but not diagnostic of, gonorrhea. A similar decree was passed by Louis IX in France in 1256, replacing regulation with banishment.[82] Similar symptoms were noted at the siege of Acre by Crusaders.

Coincidental to, or dependent on, the appearance of a gonorrhea epidemic, several changes occurred in European medieval society. Cities hired public health doctors to treat affected patients without right of refusal. Pope Boniface rescinded the requirement that physicians complete studies for the lower orders of the Catholic priesthood.[83]

Medieval public health physicians in the employ of their cities were required to treat prostitutes infected with the "burning", as well as lepers and other epidemic patients.[84] After Pope Boniface completely secularized the practice of medicine, physicians were more willing to treat a sexually transmitted infection.[83]

Research

A vaccine for gonorrhea has been developed that is effective in mice.[85] It will not be available for human use until further studies have demonstrated that it is both safe and effective in the human population. Development of a vaccine has been complicated by the ongoing evolution of resistant strains and antigenic variation (the ability of N. gonorrhoeae to disguise itself with different surface markers to evade the immune system).[59]

As N. gonorrhoeae is closely related to N. meningitidis and they have 80–90% homology in their genetic sequences some cross-protection by meningococcal vaccines is plausible. A study published in 2017 showed that MeNZB group B meningococcal vaccine provided a partial protection against gonorrhea.[86] The vaccine efficiency was calculated to be 31%.[87] In June 2023, GlaxoSmithKline won fast-track designation from the Food and Drug Administration for its vaccine candidate against gonorrhea.[88]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 "Gonorrhea – CDC Fact Sheet (Detailed Version)". 17 November 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/std/gonorrhea/stdfact-gonorrhea-detailed.htm.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Gonorrhea". Disease-a-Month 62 (8): 260–268. August 2016. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2016.03.009. PMID 27107780.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 "Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports 64 (RR-03): 1–137. June 2015. PMID 26042815.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "Antibiotic-Resistant Gonorrhea Basic Information". 13 June 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/std/gonorrhea/arg/basic.htm.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Current and future antimicrobial treatment of gonorrhoea - the rapidly evolving Neisseria gonorrhoeae continues to challenge". BMC Infectious Diseases 15: 364. August 2015. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-1029-2. PMID 26293005.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 "Global Estimates of the Prevalence and Incidence of Four Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections in 2012 Based on Systematic Review and Global Reporting". PLOS ONE 10 (12): e0143304. 8 December 2015. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143304. PMID 26646541. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1043304N.

- ↑ General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. Wolters Kluwer Health. 2017-11-27. p. 787. ISBN 978-1-4963-5453-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=jmhADwAAQBAJ&pg=PT787.

- ↑ "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet 386 (9995): 743–800. August 2015. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMID 26063472.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Emergence of multi-drug resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Report). World Health Organisation. 2012. pp. 2. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70603/1/WHO_RHR_11.14_eng.pdf.

- ↑ Wang, Haidong et al. (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 "Gonorrhea - Symptoms and causes" (in en). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/gonorrhea/symptoms-causes/syc-20351774.

- ↑ "Screening for gonorrhea and Chlamydia: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force". Annals of Internal Medicine 161 (12): 884–893. December 2014. doi:10.7326/M14-1022. PMID 25244000.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Sexually Transmitted Diseases: A Physician Tells You What You Need to Know (Second ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University. 2007. ISBN 978-0-8018-8658-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=aywGiP9w-u8C&q=gonorrhea+throat&pg=PT150.

- ↑ "Detailed STD Facts - Gonorrhea" (in en-us). 2022-04-05. https://www.cdc.gov/std/gonorrhea/stdfact-gonorrhea-detailed.htm.

- ↑ Keshvani, Neil; Gupta, Arjun; Incze, Michael A. (1 January 2019). "I Am Worried About Gonorrhea: What Do I Need to Know?". JAMA Internal Medicine 179 (1): 132. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4345. PMID 30398526. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2712562.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 "Sexually Transmitted Infections". The Urologic Clinics of North America 42 (4): 507–518. November 2015. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2015.06.004. PMID 26475947.

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 17.8 "Gonorrhoea". BMJ Clinical Evidence 2007. March 2007. PMID 19454057.

- ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 "Chlamydia trachomatis and Genital Mycoplasmas: Pathogens with an Impact on Human Reproductive Health". Journal of Pathogens 2014 (183167): 183167. 2014. doi:10.1155/2014/183167. PMID 25614838.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 19.2 "What Complications Can Gonorrhea Cause?". WebMD. 2019. https://www.webmd.com/sexual-conditions/complications-gonorrhea-cause.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 20.2 Gonorrhea. Infobase. 1 January 2009. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4381-0142-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=3iS7tXxC_HQC&pg=PA49.

- ↑ Urologic Surgical Pathology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. 24 January 2014. p. 863. ISBN 978-0-323-08619-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=wrHQAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA863.

- ↑ Jump up to: 22.0 22.1 "Sexually transmitted infections and prostate cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Cancer Epidemiology 38 (4): 329–338. August 2014. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2014.06.002. PMID 24986642.

- ↑ "Prophylaxis for Gonococcal and Chlamydial Ophthalmia Neonatorum in the Canadian Guide to Clinical Preventative Health Care". Public Health Agency of Canada. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/clinic-clinique/pdf/s1c16e.pdf.

- ↑ Jump up to: 24.0 24.1 "Complications from gonorrhea" (in en). https://stanfordhealthcare.org/medical-conditions/sexual-and-reproductive-health/gonorrhea/symptoms/complications.html.

- ↑ Jump up to: 25.0 25.1 "Gonorrhea - Symptoms and causes" (in en). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/gonorrhea/symptoms-causes/syc-20351774.

- ↑ "Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis among women reporting extragenital exposures". Sexually Transmitted Diseases 42 (5): 233–239. May 2015. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000248. PMID 25868133.

- ↑ Howard Brown Health Center: STI Annual Report, 2009

- ↑ Jump up to: 28.0 28.1 Homeopathic Guide to all Diseases Urinary and Sexual Organ. Charles Julius Hempel. Rademacher & Sheek. 1854. https://books.google.com/books?id=AzkzAQAAMAAJ&q=%22unnatural+gratification+of+the+sexual+instinct%22&pg=PA79.

- ↑ National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (20 July 2001). "Workshop Summary: Scientific Evidence on Condom Effectiveness for Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Prevention". Hyatt Dulles Airport, Herndon, Virginia. pp14

- ↑ "What is the evidence for non-sexual transmission of gonorrhoea in children after the neonatal period? A systematic review". Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine 14 (8): 489–502. November 2007. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2007.04.001. PMID 17961874.

- ↑ Gonorrhea. Infobase. 1 January 2009. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-4381-0142-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=3iS7tXxC_HQC&pg=PA48.

- ↑ Sexually transmitted diseases. McGraw-Hill. 1984. OCLC 644578106. http://worldcat.org/oclc/644578106.

- ↑ "A Randomized, Controlled Trial of inSPOT and Patient-Delivered Partner Therapy for Gonorrhea and Chlamydial Infection Among Men Who Have Sex With Men". Sexually Transmitted Diseases 40 (5): 432. May 2013. doi:10.1097/olq.0b013e31829349ec. ISSN 0148-5717.

- ↑ "The use of cephalosporins for gonorrhea: the impending problem of resistance". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 10 (4): 555–577. March 2009. doi:10.1517/14656560902731993. PMID 19284360.

- ↑ Jump up to: 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 "Emergence and spread of drug resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae". The Journal of Urology 184 (3): 851–8; quiz 1235. September 2010. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.04.078. PMID 20643433.

- ↑ Jump up to: 36.0 36.1 "Final Recommendation Statement: Chlamydia and Gonorrhea: Screening – US Preventive Services Task Force" (in en). https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/chlamydia-and-gonorrhea-screening.

- ↑ "Gonococcal Infections – 2015 STD Treatment Guidelines" (in en-us). https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/gonorrhea.htm.

- ↑ "Home-based versus clinic-based specimen collection in the management of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015 (9): CD011317. September 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011317.pub2. PMID 26418128.

- ↑ Review of medical microbiology and immunology (Thirteenth ed.). New York. 2014-07-01. ISBN 9780071818117. OCLC 871305336.

- ↑ Jump up to: 40.0 40.1 40.2 "The laboratory diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae". The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases & Medical Microbiology 16 (1): 15–25. January 2005. doi:10.1155/2005/323082. PMID 18159523.

- ↑ Jump up to: 41.0 41.1 41.2 https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/clinical.htm section on prevention methods

- ↑ Gonorrhea~overview at eMedicine

- ↑ "Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae prevalence and coinfection in adolescents entering selected US juvenile detention centers, 1997-2002". Sexually Transmitted Diseases 32 (4): 255–259. April 2005. doi:10.1097/01.olq.0000158496.00315.04. PMID 15788927.

- ↑ "Gonorrhea prevalence and coinfection with chlamydia in women in the United States, 2000". Sexually Transmitted Diseases 30 (5): 472–476. May 2003. doi:10.1097/00007435-200305000-00016. PMID 12916141.

- ↑ "Gonorrhea and chlamydia in the United States among persons 14 to 39 years of age, 1999 to 2002". Annals of Internal Medicine 147 (2): 89–96. July 2007. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-2-200707170-00007. PMID 17638719.

- ↑ "Gonococcal Infections - 2015 STD Treatment Guidelines". 2018-01-04. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/gonorrhea.htm.

- ↑ Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. 2004. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.[page needed]

- ↑ Department of Reproductive Health and Research (2011). "Emergence of multi-drug resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae – Threat of global rise in untreatable sexually transmitted infections". FactSheet WHO/RHR/11.14. World Health Organization. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2011/WHO_RHR_11.14_eng.pdf.

- ↑ "Gonorrhea – STD information from CDC" (in en-us). 2017-10-06. https://www.cdc.gov/std/gonorrhea/default.htm.

- ↑ "USPSTF recommendations for STI screening". American Family Physician 77 (6): 819–824. March 2008. PMID 18386598.

- ↑ Health Care Guideline: Routine Prenatal Care. Fourteenth Edition. By the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement July 2010.

- ↑ section: Prevention

- ↑ section: How can gonorrhea be prevented?

- ↑ "Active recall to increase HIV and STI testing: a systematic review". Sexually Transmitted Infections 91 (5): 314–323. August 2015. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2014-051930. PMID 25759476.

- ↑ Jump up to: 55.0 55.1 "Ocular manifestations of infectious skin diseases". Clinics in Dermatology 34 (2): 124–128. 2016. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2015.11.010. PMID 26903179.

- ↑ Jump up to: 56.0 56.1 Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (August 2012). "Update to CDC's Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010: oral cephalosporins no longer a recommended treatment for gonococcal infections". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 61 (31): 590–594. PMID 22874837.

- ↑ "Antibiotic-resistant gonorrhoea on the rise, new drugs needed". 7 July 2017. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2017/Antibiotic-resistant-gonorrhoea/en/.

- ↑ "The impact of antimicrobials on gonococcal evolution". Nature Microbiology 4 (11): 1941–1950. November 2019. doi:10.1038/s41564-019-0501-y. PMID 31358980.

- ↑ Jump up to: 59.0 59.1 59.2 "Proteomics of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: the treasure hunt for countermeasures against an old disease". Frontiers in Microbiology 6: 1190. 2015. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.01190. PMID 26579097.

- ↑ "Efficacy of ertapenem, gentamicin, fosfomycin, and ceftriaxone for the treatment of anogenital gonorrhoea (NABOGO): a randomised, non-inferiority trial". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases 22 (5): 706–717. May 2022. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00625-3. PMID 35065063.

- ↑ "Antibiotic Ertapenem is alternative drug in treatment of gonorrhea". 20 January 2022. https://www.amsterdamumc.org/en/research/institutes/amsterdam-institute-for-infection-and-immunity/news/antibiotic-ertapenem-is-alternative-drug-in-treatment-of-gonorrhea.htm.

- ↑ "Bacterial conjunctivitis". BMJ Clinical Evidence 2012. February 2012. PMID 22348418.

- ↑ "Ocular Prophylaxis for Gonococcal Ophthalmia Neonatorum: US Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement". JAMA 321 (4): 394–398. January 2019. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.21367. PMID 30694327.

- ↑ "Expedited partner therapy in the management of sexually transmitted diseases" . February 2006. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- ↑ "Gonorrhea – CDC Fact Sheet". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 14 July 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/std/Gonorrhea/STDFact-gonorrhea.htm.

- ↑ "Sex and the Superbug". The New Yorker LXXXVIII (30): 26–31. 2012-10-01. http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2012/10/01/121001fa_fact_groopman. Retrieved 2012-10-13. "...public-health experts [see]...the emergence of a strain of gonorrhea that is resistant to the last drug available against it, and the harbinger of a sexually transmitted global epidemic.".

- ↑ "Extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Neisseria gonorrhoeae causing possible gonorrhoea treatment failure with ceftriaxone plus azithromycin in Austria, April 2022". Euro Surveillance 27 (24). June 2022. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.24.2200455. PMID 35713023.

- ↑ "WHO guidelines for the treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae". World Health Organization. 2016. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/gonorrhoea-treatment-guidelines/en/.

- ↑ Jump up to: 69.0 69.1 Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson; & Mitchell, Richard N. (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. pp. 705–706 ISBN:978-1-4160-2973-1

- ↑ "Epidemiology of gonorrhoea: a global perspective". Sexual Health (United States National Library of Medicine) 16 (5): 401–411. September 2019. doi:10.1071/SH19061. PMID 31505159.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet 385 (9963): 117–171. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMID 25530442.

- ↑ "Gonorrhea – CDC Fact Sheet". CDC. 29 May 2012. https://www.cdc.gov/std/Gonorrhea/STDFact-gonorrhea.htm.

- ↑ "CDC – STD Surveillance – Gonorrhea". https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats/gonorrhea.htm.

- ↑ "CDC Fact Sheet – Chlamydia". https://www.cdc.gov/std/Chlamydia/STDFact-Chlamydia.htm.

- ↑ "STD Trends in the United States: 2010 National Data for Gonorrhea, Chlamydia, and Syphilis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 22 November 2010. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats10/tables/trends-table.htm.

- ↑ "Untreatable gonorrhoea 'superbug' spreading around world, WHO warns". The Daily Telegraph. 7 July 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/jul/07/untreatable-gonorrhoea-superbug-spreading-around-world-who-warns.

- ↑ "Daf Parashat Hashavua". http://www.biu.ac.il/JH/Parasha/eng/metzora/nitzan.html.

- ↑ The Mirror for Magistrates. 1587. as cited in the Oxford English Dictionary entry for "clap".

- ↑ "Ueber neuere Antigonorrhoica (insbes. Argonin und Protargol)". Archives of Dermatological Research 43 (1): 31–36. 1898. doi:10.1007/BF01986890. https://zenodo.org/record/2135400.

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Neonatal Conjunctivitis

- ↑ History of Prostitution. New York: Harper. 1910.

- ↑ The History of Prostitution. 2. New Yory: MacMillan. 1931.

- ↑ Jump up to: 83.0 83.1 Basic Healthcare Studies: Sexually Transmitted Disease. Alpha Editions. 2017. ISBN 9789386367570. https://books.google.com/books?id=iwU1DgAAQBAJ&pg=PT70.

- ↑ History of European Morals. New York: MacMillan. 1926.

- ↑ "Vaccines against gonorrhea: current status and future challenges". Vaccine 32 (14): 1579–1587. March 2014. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.067. PMID 24016806.

- ↑ "Future prospects for new vaccines against sexually transmitted infections". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 30 (1): 77–86. February 2017. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000343. PMID 27922851.

- ↑ "Effectiveness of a group B outer membrane vesicle meningococcal vaccine against gonorrhoea in New Zealand: a retrospective case-control study". Lancet 390 (10102): 1603–1610. September 2017. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31449-6. PMID 28705462.

- ↑ "GSK's gonorrhoea vaccine receives FDA's 'fast-track' designation". Reuters. 27 June 2023. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/gsks-gonorrhoea-vaccine-receives-fdas-fast-track-designation-2023-06-27/.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|