Biology:Notch proteins

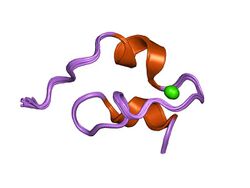

| Notch (LNR) domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Structure of a prototype LNR module from human Notch 1[1] | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Notch | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00066 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000800 | ||||||||

| SMART | SM00004 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PS50258 | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 462 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 5kzo | ||||||||

| Membranome | 19 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Notch proteins are a family of type 1 transmembrane proteins that form a core component of the Notch signaling pathway, which is highly conserved in metazoans. The Notch extracellular domain mediates interactions with DSL family ligands, allowing it to participate in juxtacrine signaling. The Notch intracellular domain acts as a transcriptional activator when in complex with CSL family transcription factors. Members of this type 1 transmembrane protein family share several core structures, including an extracellular domain consisting of multiple epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like repeats and an intracellular domain transcriptional activation domain (TAD). Notch family members operate in a variety of different tissues and play a role in a variety of developmental processes by controlling cell fate decisions. Much of what is known about Notch function comes from studies done in Caenorhabditis elegans (C.elegans) and Drosophila melanogaster. Human homologs have also been identified, but details of Notch function and interactions with its ligands are not well known in this context.

Discovery

Notch was discovered in a mutant Drosophila in March 1913 in the lab of Thomas Hunt Morgan.[2] This mutant emerged after several generations of crossing out and back-crossing beaded winged flies with wild type flies and was first characterized by John S. Dexter.[3] The most frequently observed phenotype in Notch mutant flies is the appearance of a concave serration at the most distal end of the wings, for which the gene is named, accompanied by the absence of marginal bristles.[4][5] This mutant was found to be a sex-linked dominant on the X chromosome that could only be observed in heterozygous females as it was lethal in males and homozygous females.[2] The first Notch allele was established in 1917 by C.W. Metz and C.B. Bridges.[6] In the late 1930s, studies of fly embryogenesis done by Donald F. Poulson provided the first indication of Notch's role in development.[7] Notch-8 mutant males exhibited a lack of the inner germ layers, the endoderm and mesoderm, that resulted in failure to undergo later morphogenesis embryonic lethality. Later studies in early Drosophila neurogenesis provided some of the first indications of Notch's roll in cell-cell signaling, as the nervous system in Notch mutants was developed by sacrificing hypodermal cells.[8]

Starting in the 1980s researchers began to gain further insights into Notch function through genetic and molecular experiments. Genetic screens conducted in Drosophila led to the identification of several proteins that play a central role in Notch signaling, including Enhancer of split,[8] Master mind, Delta,[9] Suppressor of Hairless (CSL),[10] and Serrate.[11] At the same time, the Notch gene was successfully sequenced[12][13] and cloned,[14][15] providing insights into the molecular architecture of Notch proteins and led to identification of Notch homologs in Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans)[16][17][18] and eventually in mammals.

In the early 1990s Notch was increasingly implicated as the receptor of a previously unknown intercellular signal pathway[19][20] in which the Notch intercellular domain (NICD) is transported to the nucleus where it acts as a transcription factor to directly regulate target genes.[21][22][23] The release of the NICD was found to be as a result of proteolytic cleavage of the transmembrane protein through the actions of the γ-secretase complex catalytic subunit Presenilin. This was a significant interaction as Presenilin is implicated in the development of Alzheimer's disease.[24] This and further research into the mechanism of Notch signaling led to research that would further connect Notch to a wide range of human diseases.

Structure

Drosophila contain a single Notch protein, C. elegans contain two redundant notch paralogs, Lin-12[25] and GLP-1,[18][26] and humans have four Notch variants, Notch 1-4. Although variations exist between homologs, there are a set of highly conserved structures found in all Notch family proteins. The protein can broadly be split into the Notch extracellular domain (NECD) and Notch intracellular domain (NICD) joined together by a single-pass transmembrane domain (TM).

The NECD contains 36 EGF repeats in Drosophila,[13] 28-36 in humans, and 13 and 10 in C. elegans Lin-12 and GLP-1 respectively.[27] These repeats are heavily modified through O-glycoslyation[28] and the addition of specific O-linked glycans has been shown to be necessary for proper function. The EGF repeats are followed by three cysteine-rich Lin-12/Notch Repeats (LNR) and a heterodimerization (HD) domain. Together the LNR and HD compose the negative regulatory region adjacent to the cell membrane and help prevent signaling in the absence of ligand binding.

NICD acts as a transcription factor that is released after ligand binding triggers its cleavage. It contains a nuclear localization sequence (NLS) that mediates its translocation to the nucleus, where it forms a transcriptional complex along with several other transcription factors. Once in the nucleus, several ankyrin repeats and the RAM domain interactions between the NICD and CSL proteins to form a transcriptional activation complex.[29] In humans, an additional PEST domain plays a role in NICD degradation.[30]

Function

Notch family members play a role in a variety of developmental processes by controlling cell fate decisions. The Notch signaling network is an evolutionarily conserved intercellular signaling pathway that regulates interactions between physically adjacent cells. In Drosophila, notch interaction with its cell-bound ligands (delta, serrate) establishes an intercellular signaling pathway that plays a key role in development. This protein functions as a receptor for membrane bound ligands, and may play multiple roles during development.[31] A deficiency can be associated with bicuspid aortic valve.[32]

There is evidence that activated Notch 1 and Notch 3 promote differentiation of progenitor cells into astroglia.[33] Notch 1, then activated before birth, induces radial glia differentiation,[34] but postnatally induces the differentiation into astrocytes.[35] One study shows that Notch-1 cascade is activated by Reelin in an unidentified way.[36] Reelin and Notch1 cooperate in the development of the dentate gyrus, according to another.[37]

Ligand interactions

| Jagged/Serrate protein | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | DSL | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01414 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR026219 | ||||||||

| Membranome | 76 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

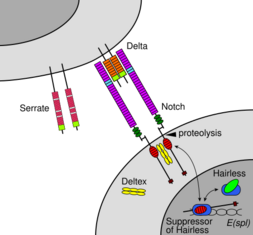

Notch signaling is triggered via direct cell-to-cell contact, mediated by interactions between the Notch receptor protein in the signal receiving cell and a ligand in an adjacent signal transmitting cell. These type 1 single-pass transmembrane proteins fall into the Delta/Serrate/Lag-2 (DSL) family of proteins which is named after the three canonical Notch ligands.[19] Delta and Serrate are found in Drosophila while Lag-2 is found in C. elegans. Humans contain 3 Delta homologs, Delta-like 1, 3, and 4, as well as two Serrate homologs, Jagged 1 and 2. Notch proteins consist of a relatively short intracellular domain and a large extracellular domain with one or more EGF motifs and a N-terminal DSL-binding motif. EGF repeats 11-12 on the Notch extracellular domain have been shown to be necessary and sufficient for trans signaling interactions between Notch and its ligands.[38] Additionally, EGF repeats 24-29 have been implicated in inhibition of cis interactions between Notch and ligands co-expressed in the same cell.[39]

Proteolysis

In order for a signaling event to occur, the Notch protein must be cleaved at several sites. In humans, Notch is first cleaved in the NRR domain by furin while being processed in the trans-Golgi network before being presented on the cell surface as a heterodimer.[40][41] Drosophila Notch does not require this cleavage for signaling to occur,[42] and there is some evidence that suggests that LIN-12 and GLP-1 are cleaved at this site in C. elegans.

Release of the NICD is achieved after an additional two cleavage events to Notch. Binding of Notch to a DSL ligand results in a conformational change that exposes a cleavage site in the NECD. Enzymatic proteolysis at this site is carried out by a A Disintegrin and Metalloprotease domain (ADAM) family protease. This protein is called Kuzbanian in Drosophila,[43][44] sup-17 in C. elegans,[45] and ADAM10 in humans.[46][47] After proteolytic cleavage, the released NECD is endocytosed into the signal transmitting cell, leaving behind only a small extracellular portion of Notch. This truncated Notch protein can then be recognized by a γ-secretase that cleaves the third site found in the TM domain.[48]

Human homologs

Notch-1

Notch-2

Notch-2 (Neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 2) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the NOTCH2 gene.[49]

NOTCH2 is associated with Alagille syndrome[50] and Hajdu–Cheney syndrome.[51]

Notch-3

Notch-4

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Nuclear magnetic resonance structure of a prototype Lin12-Notch repeat module from human Notch1". Biochemistry 42 (23): 7061–7. June 2003. doi:10.1021/bi034156y. PMID 12795601.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Morgan, Thomas Hunt; Bridges, Calvin B. (1916). Sex-linked inheritance in Drosophila. NCSU Libraries. Washington, Carnegie Institution of Washington. https://archive.org/details/sexlinkedinherit00morg.

- ↑ Dexter, John S. (December 1914). "The Analysis of a Case of Continuous Variation in Drosophila by a Study of Its Linkage Relations". The American Naturalist 48 (576): 712–758. doi:10.1086/279446.

- ↑ "Character Changes Caused by Mutation of an Entire Region of a Chromosome in Drosophila". Genetics 4 (3): 275–82. May 1919. doi:10.1093/genetics/4.3.275. PMID 17245926.

- ↑ Lindsley, Dan L.; Zimm, Georgianna G. (2012-12-02). The Genome of Drosophila Melanogaster. Academic Press. ISBN 9780323139847. https://books.google.com/books?id=sklm5UmoGykC&pg=PP1.

- ↑ "Incompatibility of Mutant Races in Drosophila". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 3 (12): 673–8. December 1917. doi:10.1073/pnas.3.12.673. PMID 16586764. Bibcode: 1917PNAS....3..673M.

- ↑ "Chromosomal Deficiencies and the Embryonic Development of Drosophila Melanogaster". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 23 (3): 133–7. March 1937. doi:10.1073/pnas.23.3.133. PMID 16588136. Bibcode: 1937PNAS...23..133P.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "On the phenotype and development of mutants of early neurogenesis inDrosophila melanogaster". Wilhelm Roux's Archives of Developmental Biology 192 (2): 62–74. March 1983. doi:10.1007/BF00848482. PMID 28305500.

- ↑ "Mutations of early neurogenesis inDrosophila". Wilhelm Roux's Archives of Developmental Biology 190 (4): 226–229. July 1981. doi:10.1007/BF00848307. PMID 28305572.

- ↑ "The suppressor of hairless protein participates in notch receptor signaling". Cell 79 (2): 273–82. October 1994. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90196-1. PMID 7954795.

- ↑ "The gene Serrate encodes a putative EGF-like transmembrane protein essential for proper ectodermal development in Drosophila melanogaster". Genes & Development 4 (12A): 2188–201. December 1990. doi:10.1101/gad.4.12a.2188. PMID 2125287.

- ↑ "Sequence of the notch locus of Drosophila melanogaster: relationship of the encoded protein to mammalian clotting and growth factors". Molecular and Cellular Biology 6 (9): 3094–108. September 1986. doi:10.1128/mcb.6.9.3094. PMID 3097517.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Nucleotide sequence from the neurogenic locus notch implies a gene product that shares homology with proteins containing EGF-like repeats". Cell 43 (3 Pt 2): 567–81. December 1985. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(85)90229-6. PMID 3935325.

- ↑ "The Notch locus of Drosophila melanogaster". Cell 34 (2): 421–33. September 1983. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(83)90376-8. PMID 6193889.

- ↑ "Molecular cloning of Notch, a locus affecting neurogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 80 (7): 1977–81. April 1983. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.7.1977. PMID 6403942. Bibcode: 1983PNAS...80.1977A.

- ↑ "The lin-12 locus of Caenorhabditis elegans". BioEssays 6 (2): 70–3. February 1987. doi:10.1002/bies.950060207. PMID 3551950.

- ↑ "The glp-1 locus and cellular interactions in early C. elegans embryos". Cell 51 (4): 601–11. November 1987. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90129-2. PMID 3677169.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "glp-1 is required in the germ line for regulation of the decision between mitosis and meiosis in C. elegans". Cell 51 (4): 589–99. November 1987. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90128-0. PMID 3677168.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Notch signaling". Science 268 (5208): 225–32. April 1995. doi:10.1126/science.7716513. PMID 7716513. Bibcode: 1995Sci...268..225A.

- ↑ "Making a difference: the role of cell-cell interactions in establishing separate identities for equivalent cells". Cell 68 (2): 271–81. January 1992. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90470-w. PMID 1365402.

- ↑ "Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain". Nature 393 (6683): 382–6. May 1998. doi:10.1038/30756. PMID 9620803. Bibcode: 1998Natur.393..382S.

- ↑ "The intracellular domain of mouse Notch: a constitutively activated repressor of myogenesis directed at the basic helix-loop-helix region of MyoD". Development 120 (9): 2385–96. September 1994. doi:10.1242/dev.120.9.2385. PMID 7956819.

- ↑ "Intrinsic activity of the Lin-12 and Notch intracellular domains in vivo". Cell 74 (2): 331–45. July 1993. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90424-o. PMID 8343960.

- ↑ "Cloning of a gene bearing missense mutations in early-onset familial Alzheimer's disease" (in En). Nature 375 (6534): 754–60. June 1995. doi:10.1038/375754a0. PMID 7596406. Bibcode: 1995Natur.375..754S.

- ↑ "The lin-12 locus specifies cell fates in Caenorhabditis elegans". Cell 34 (2): 435–44. September 1983. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(83)90377-x. PMID 6616618.

- ↑ "Transcript analysis of glp-1 and lin-12, homologous genes required for cell interactions during development of C. elegans". Cell 58 (3): 565–71. August 1989. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(89)90437-6. PMID 2758467.

- ↑ "lin-12, a nematode homeotic gene, is homologous to a set of mammalian proteins that includes epidermal growth factor". Cell 43 (3 Pt 2): 583–90. December 1985. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(85)90230-2. PMID 3000611.

- ↑ "O-glycosylation of EGF repeats: identification and initial characterization of a UDP-glucose: protein O-glucosyltransferase". Glycobiology 12 (11): 763–70. November 2002. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwf085. PMID 12460944.

- ↑ "Physical interaction between a novel domain of the receptor Notch and the transcription factor RBP-J kappa/Su(H)". Current Biology 5 (12): 1416–23. December 1995. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(95)00279-X. PMID 8749394.

- ↑ "Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Science 306 (5694): 269–71. October 2004. doi:10.1126/science.1102160. PMID 15472075. Bibcode: 2004Sci...306..269W.

- ↑ "Entrez Gene: NOTCH1 Notch homolog 1, translocation-associated (Drosophila)". https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=gene&Cmd=ShowDetailView&TermToSearch=4851.

- ↑ "Novel NOTCH1 mutations in patients with bicuspid aortic valve disease and thoracic aortic aneurysms". The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 134 (2): 290–6. August 2007. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.02.041. PMID 17662764.

- ↑ "Notch1 and Notch3 instructively restrict bFGF-responsive multipotent neural progenitor cells to an astroglial fate". Neuron 29 (1): 45–55. January 2001. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00179-9. PMID 11182080.

- ↑ "Radial glial identity is promoted by Notch1 signaling in the murine forebrain". Neuron 26 (2): 395–404. May 2000. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81172-1. PMID 10839358.

- ↑ "Spatiotemporal selectivity of response to Notch1 signals in mammalian forebrain precursors". Development 128 (5): 689–702. March 2001. doi:10.1242/dev.128.5.689. PMID 11171394. http://dev.biologists.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11171394.

- ↑ "Reelin induces a radial glial phenotype in human neural progenitor cells by activation of Notch-1". BMC Developmental Biology 8 (1): 69. July 2008. doi:10.1186/1471-213X-8-69. PMID 18593473.

- ↑ "Reelin and Notch1 cooperate in the development of the dentate gyrus". The Journal of Neuroscience 29 (26): 8578–85. July 2009. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0958-09.2009. PMID 19571148.

- ↑ "Specific EGF repeats of Notch mediate interactions with Delta and Serrate: implications for Notch as a multifunctional receptor". Cell 67 (4): 687–99. November 1991. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90064-6. PMID 1657403.

- ↑ "The Abruptex domain of Notch regulates negative interactions between Notch, its ligands and Fringe". Development 127 (6): 1291–302. March 2000. doi:10.1242/dev.127.6.1291. PMID 10683181. http://dev.biologists.org/content/127/6/1291.

- ↑ "Intracellular cleavage of Notch leads to a heterodimeric receptor on the plasma membrane". Cell 90 (2): 281–91. July 1997. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80336-0. PMID 9244302.

- ↑ "The Notch1 receptor is cleaved constitutively by a furin-like convertase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95 (14): 8108–12. July 1998. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.14.8108. PMID 9653148. Bibcode: 1998PNAS...95.8108L.

- ↑ "Furin cleavage is not a requirement for Drosophila Notch function". Mechanisms of Development 115 (1–2): 41–51. July 2002. doi:10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00120-x. PMID 12049766.

- ↑ "KUZ, a conserved metalloprotease-disintegrin protein with two roles in Drosophila neurogenesis". Science 273 (5279): 1227–31. August 1996. doi:10.1126/science.273.5279.1227. PMID 8703057. Bibcode: 1996Sci...273.1227R.

- ↑ "Kuzbanian controls proteolytic processing of Notch and mediates lateral inhibition during Drosophila and vertebrate neurogenesis". Cell 90 (2): 271–80. July 1997. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80335-9. PMID 9244301.

- ↑ "SUP-17, a Caenorhabditis elegans ADAM protein related to Drosophila KUZBANIAN, and its role in LIN-12/NOTCH signalling". Development 124 (23): 4759–67. December 1997. doi:10.1242/dev.124.23.4759. PMID 9428412.

- ↑ "Membrane-associated metalloproteinase recognized by characteristic cleavage of myelin basic protein: Assay and isolation". Proteolytic Enzymes: Aspartic and Metallo Peptidases. Methods in Enzymology. 248. 1995. pp. 388–95. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(95)48025-0. ISBN 9780121821494.

- ↑ "Purification of ADAM 10 from bovine spleen as a TNFalpha convertase". FEBS Letters 400 (3): 333–5. January 1997. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01410-x. PMID 9009225.

- ↑ "Requirements for presenilin-dependent cleavage of notch and other transmembrane proteins". Molecular Cell 6 (3): 625–36. September 2000. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00061-7. PMID 11030342.

- ↑ "The human NOTCH1, 2, and 3 genes are located at chromosome positions 9q34, 1p13-p11, and 19p13.2-p13.1 in regions of neoplasia-associated translocation". Genomics 24 (2): 253–8. November 1994. doi:10.1006/geno.1994.1613. PMID 7698746.

- ↑ "Screening for Alagille syndrome mutations in the JAG1 and NOTCH2 genes using denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography". Genetic Testing 11 (3): 216–27. 2007. doi:10.1089/gte.2006.0519. PMID 17949281.

- ↑ "Mutations in NOTCH2 cause Hajdu-Cheney syndrome, a disorder of severe and progressive bone loss". Nature Genetics 43 (4): 303–5. March 2011. doi:10.1038/ng.779. PMID 21378985.

References

- "Sequence of C. elegans lag-2 reveals a cell-signalling domain shared with Delta and Serrate of Drosophila". Nature 368 (6467): 150–4. March 1994. doi:10.1038/368150a0. PMID 8139658. Bibcode: 1994Natur.368..150T.

- "Jagged: a mammalian ligand that activates Notch1". Cell 80 (6): 909–17. March 1995. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90294-5. PMID 7697721.

- "Mutations altering the structure of epidermal growth factor-like coding sequences at the Drosophila Notch locus". Cell 51 (4): 539–48. November 1987. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90123-1. PMID 3119223.

|