Biology:Pepsin

| pepsin B | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC number | 3.4.23.2 | ||||||||

| CAS number | 9025-48-3 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| pepsin C (gastricsin) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC number | 3.4.23.3 | ||||||||

| CAS number | 9012-71-9 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| |||||||||

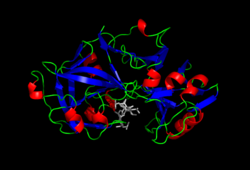

Pepsin /ˈpɛpsɪn/ is an endopeptidase that breaks down proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids. It is produced in the gastric chief cells of the stomach lining and is one of the main digestive enzymes in the digestive systems of humans and many other animals, where it helps digest the proteins in food. Pepsin is an aspartic protease, using a catalytic aspartate in its active site.[2]

It is one of three principal endopeptidases (enzymes cutting proteins in the middle) in the human digestive system, the other two being chymotrypsin and trypsin. There are also exopeptidases which remove individual amino acids at both ends of proteins (carboxypeptidases produced by the pancreas and aminopeptidases secreted by the small intestine). During the process of digestion, these enzymes, each of which is specialized in severing links between particular types of amino acids, collaborate to break down dietary proteins into their components, i.e., peptides and amino acids, which can be readily absorbed by the small intestine. The cleavage specificity of pepsin is broad, but some amino acids like tyrosine, phenylalanine and tryptophan increase the probability of cleavage.[3]

Pepsin's proenzyme, pepsinogen, is released by the gastric chief cells in the stomach wall, and upon mixing with the hydrochloric acid of the gastric juice, pepsinogen activates to become pepsin.[2]

History

Pepsin was one of the first enzymes to be discovered, by Theodor Schwann in 1836. Schwann coined its name from the Greek word πέψις pepsis, meaning "digestion" (from πέπτειν peptein "to digest").[4][5][6][7] An acidic substance that was able to convert nitrogen-based foods into water-soluble material was determined to be pepsin.[8]

In 1928, it became one of the first enzymes to be crystallized when John H. Northrop crystallized it using dialysis, filtration, and cooling.[9]

Precursor

Pepsin is expressed as a zymogen called pepsinogen, whose primary structure has an additional 44 amino acids compared to the active enzyme.

In the stomach, gastric chief cells release pepsinogen. This zymogen is activated by hydrochloric acid (HCl), which is released from parietal cells in the stomach lining. The hormone gastrin and the vagus nerve trigger the release of both pepsinogen and HCl from the stomach lining when food is ingested. Hydrochloric acid creates an acidic environment, which allows pepsinogen to unfold and cleave itself in an autocatalytic fashion, thereby generating pepsin (the active form). Pepsin cleaves the 44 amino acids from pepsinogen to create more pepsin.

Pepsinogens are mainly grouped in 5 different groups based on their primary structure: pepsinogen A (also called pepsinogen I), pepsinogen B, progastricsin (also called pepsinogen II and pepsinogen C), prochymosin (also called prorennin) and pepsinogen F (also called pregnancy-associated glycoprotein).[10]

Activity and stability

Pepsin is most active in acidic environments between pH 1.5 to 2.5.[11][12] Accordingly, its primary site of synthesis and activity is in the stomach (pH 1.5 to 2). In humans the concentration of pepsin in the stomach reaches 0.5 – 1 mg/mL.[13][14]

Pepsin is inactive at pH 6.5 and above, however pepsin is not fully denatured or irreversibly inactivated until pH 8.0.[11][15] Therefore, pepsin in solutions of up to pH 8.0 can be reactivated upon re-acidification. The stability of pepsin at high pH has significant implications on disease attributed to laryngopharyngeal reflux. Pepsin remains in the larynx following a gastric reflux event.[16][17] At the mean pH of the laryngopharynx (pH = 6.8) pepsin would be inactive but could be reactivated upon subsequent acid reflux events resulting in damage to local tissues.

Pepsin exhibits a broad cleavage specificity. Pepsin will digest up to 20% of ingested amide bonds.[18] Residues in the P1 and P1' positions[19] are most important in determining cleavage probability. Generally, hydrophobic amino acids at P1 and P1' positions increase cleavage probability. Phenylalanine, leucine and methionine at the P1 position, and phenylalanine, tryptophan and tyrosine at the P1' position result in the highest cleavage probability.[3][18]: 675 Cleavage is disfavoured by positively charged amino acids histidine, lysine and arginine at the P1 position.[3]

In laryngopharyngeal reflux

Pepsin is one of the primary causes of mucosal damage during laryngopharyngeal reflux.[20][21] Pepsin remains in the larynx (pH 6.8) following a gastric reflux event.[16][17] While enzymatically inactive in this environment, pepsin would remain stable and could be reactivated upon subsequent acid reflux events.[15] Exposure of laryngeal mucosa to enzymatically active pepsin, but not irreversibly inactivated pepsin or acid, results in reduced expression of protective proteins and thereby increases laryngeal susceptibility to damage.[15][16][17]

Pepsin may also cause mucosal damage during weakly acidic or non-acid gastric reflux. Weak or non-acid reflux is correlated with reflux symptoms and mucosal injury.[22][23][24][25] Under non-acid conditions (neutral pH), pepsin is internalized by cells of the upper airways such as the larynx and hypopharynx by a process known as receptor-mediated endocytosis.[26] The receptor by which pepsin is endocytosed is currently unknown. Upon cellular uptake, pepsin is stored in intracellular vesicles of low pH at which its enzymatic activity would be restored. Pepsin is retained within the cell for up to 24 hours.[27] Such exposure to pepsin at neutral pH and endocyctosis of pepsin causes changes in gene expression associated with inflammation, which underlies signs and symptoms of reflux,[28] and tumor progression.[29] This and other research[30] implicates pepsin in carcinogenesis attributed to gastric reflux.

Pepsin in airway specimens is considered to be a sensitive and specific marker for laryngopharyngeal reflux.[31][32] Research to develop new pepsin-targeted therapeutic and diagnostic tools for gastric reflux is ongoing. A rapid non-invasive pepsin diagnostic called Peptest is now available which determines the presence of pepsin in saliva samples.[33]

Inhibitors

Pepsin may be inhibited by high pH (see Activity and stability) or by inhibitor compounds. Pepstatin is a low molecular weight compound and potently inhibitor specific for acid proteases with an inhibitory dissociation constant (Ki) of about 10−10 M for pepsin. The statyl residue of pepstatin is thought to be responsible for pepstatin inhibition of pepsin; statine is a potential analog of the transition state for catalysis by pepsin and other acid proteases. Pepstatin does not covalently bind pepsin and inhibition of pepsin by pepstatin is therefore reversible.[34] 1-bis(diazoacetyl)-2-phenylethane reversibly inactivates pepsin at pH 5, a reaction which is accelerated by the presence of Cu(II).[35]

Porcine pepsin is inhibited by pepsin inhibitor-3 (PI-3) produced by the large roundworm of pig (Ascaris suum).[36] PI-3 occupies the active site of pepsin using its N-terminal residues and thereby blocks substrate binding. Amino acid residues 1 - 3 (Gln-Phe-Leu) of mature PI-3 bind to P1' - P3' positions of pepsin. The N-terminus of PI-3 in the PI-3:pepsin complex is positioned by hydrogen bonds which form an eight-stranded β-sheet, where three strands are contributed by pepsin and five by PI-3.[36]

A product of protein digestion by pepsin inhibits the reaction.[37][38]

Sucralfate, a drug used to treat stomach ulcers and other pepsin-related conditions, also inhibits pepsin activity.[39]

Applications

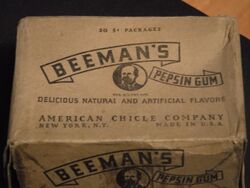

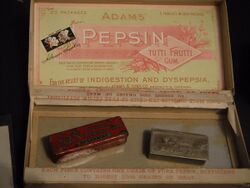

Commercial pepsin is extracted from the glandular layer of hog stomachs. It is a component of rennet used to curdle milk during the manufacture of cheese. Pepsin is used for a variety of applications in food manufacturing: to modify and provide whipping qualities to soy protein and gelatin,[40] to modify vegetable proteins for use in nondairy snack items, to make precooked cereals into instant hot cereals,[41] and to prepare animal and vegetable protein hydrolysates for use in flavoring foods and beverages. It is used in the leather industry to remove hair and residual tissue from hides and in the recovery of silver from discarded photographic films by digesting the gelatin layer that holds the silver.[42] Pepsin was historically an additive of Beeman's gum brand chewing gum by Dr. Edwin E. Beeman.

Pepsin is commonly used in the preparation of F(ab')2 fragments from antibodies. In some assays, it is preferable to use only the antigen-binding (Fab) portion of the antibody. For these applications, antibodies may be enzymatically digested to produce either an Fab or an F(ab')2 fragment of the antibody. To produce an F(ab')2 fragment, IgG is digested with pepsin, which cleaves the heavy chains near the hinge region.[43] One or more of the disulfide bonds that join the heavy chains in the hinge region are preserved, so the two Fab regions of the antibody remain joined together, yielding a divalent molecule (containing two antibody binding sites), hence the designation F(ab')2. The light chains remain intact and attached to the heavy chain. The Fc fragment is digested into small peptides. Fab fragments are generated by cleavage of IgG with papain instead of pepsin. Papain cleaves IgG above the hinge region containing the disulfide bonds that join the heavy chains, but below the site of the disulfide bond between the light chain and heavy chain. This generates two separate monovalent (containing a single antibody binding site) Fab fragments and an intact Fc fragment. The fragments can be purified by gel filtration, ion exchange, or affinity chromatography.[44]

Fab and F(ab')2 antibody fragments are used in assay systems where the presence of the Fc region may cause problems. In tissues such as lymph nodes or spleen, or in peripheral blood preparations, cells with Fc receptors (macrophages, monocytes, B lymphocytes, and natural killer cells) are present which can bind the Fc region of intact antibodies, causing background staining in areas that do not contain the target antigen. Use of F(ab')2 or Fab fragments ensures that the antibodies are binding to the antigen and not Fc receptors. These fragments may also be desirable for staining cell preparations in the presence of plasma, because they are not able to bind complement, which could lyse the cells. F(ab')2, and to a greater extent Fab, fragments allow more exact localization of the target antigen, i.e., in staining tissue for electron microscopy. The divalency of the F(ab')2 fragment enables it to cross-link antigens, allowing use for precipitation assays, cellular aggregation via surface antigens, or rosetting assays.[45]

Genes

The following three genes encode identical human pepsinogen A enzymes:

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A fourth human gene encodes gastricsin also known as pepsinogen C:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ PDB: 1PSO; "Crystal structure of human pepsin and its complex with pepstatin". Protein Science 4 (5): 960–72. May 1995. doi:10.1002/pro.5560040516. PMID 7663352.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Enzyme entry 3.4.23.1". SIB. http://enzyme.expasy.org/EC/3.4.23.1.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Specificity of immobilized porcine pepsin in H/D exchange compatible conditions". Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 22 (7): 1041–6. April 2008. doi:10.1002/rcm.3467. PMID 18327892. Bibcode: 2008RCMS...22.1041H.

- ↑ "[Discovery of pepsin by Theodor Schwann]" (in fr). Revue Médicale de Liège 12 (5): 139–44. March 1957. PMID 13432398.

- ↑ Asimov, Isaac (1980). A short history of biology. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. pp. 95. ISBN 9780313225833.

- ↑ "Pepsin". https://www.etymonline.com/word/pepsin.

- ↑ πέψις, πέπτειν. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ "A history of pepsin and related enzymes". The Quarterly Review of Biology 77 (2): 127–47. June 2002. doi:10.1086/340729. PMID 12089768.

- ↑ "Crystalline pepsin". Science 69 (1796): 580. May 1929. doi:10.1126/science.69.1796.580. PMID 17758437. Bibcode: 1929Sci....69..580N.

- ↑ "Pepsinogens, progastricsins, and prochymosins: structure, function, evolution, and development". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 59 (2): 288–306. February 2002. doi:10.1007/s00018-002-8423-9. PMID 11915945.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "pH stability and activity curves of pepsin with special reference to their clinical importance". Gut 6 (5): 506–8. October 1965. doi:10.1136/gut.6.5.506. PMID 4158734.

- ↑ "Information on EC 3.4.23.1 - pepsin A". BRENDA-enzymes. http://www.brenda-enzymes.org/enzyme.php?ecno=3.4.23.1#pH%20OPTIMUM.

- ↑ "Bacterial killing in gastric juice--effect of pH and pepsin on Escherichia coli and Helicobacter pylori". Journal of Medical Microbiology 55 (Pt 9): 1265–1270. September 2006. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.46611-0. PMID 16914658.

- ↑ "INFOGEST static in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal food digestion". Nature Protocols 14 (4): 991–1014. April 2019. doi:10.1038/s41596-018-0119-1. PMID 30886367.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "Activity/stability of human pepsin: implications for reflux attributed laryngeal disease". The Laryngoscope 117 (6): 1036–9. June 2007. doi:10.1097/MLG.0b013e31804154c3. PMID 17417109.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Pepsin and carbonic anhydrase isoenzyme III as diagnostic markers for laryngopharyngeal reflux disease". The Laryngoscope 114 (12): 2129–34. December 2004. doi:10.1097/01.mlg.0000149445.07146.03. PMID 15564833.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Effect of pepsin on laryngeal stress protein (Sep70, Sep53, and Hsp70) response: role in laryngopharyngeal reflux disease". The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology 115 (1): 47–58. January 2006. doi:10.1177/000348940611500108. PMID 16466100.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Cox, Michael; Nelson, David R.; Lehninger, Albert L (2008). Lehninger principles of biochemistry. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. pp. 96. ISBN 978-0-7167-7108-1. https://archive.org/details/lehningerprincip00lehn_1.

- ↑ The P1 and P1' positions refer to the amino acid residues immediately next to the bond to be cleaved, on the carboxyl and amino side respectively. See "On the active site of proteases. 3. Mapping the active site of papain; specific peptide inhibitors of papain". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 32 (5): 898–902. September 1968. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(68)90326-4. PMID 5682314.

- ↑ "Role of acid and pepsin in acute experimental esophagitis". Gastroenterology 56 (2): 223–30. February 1969. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(69)80121-6. PMID 4884956.

- ↑ "Role of the components of the gastroduodenal contents in experimental acid esophagitis". Surgery 92 (2): 276–84. August 1982. PMID 6808683.

- ↑ "Omeprazole does not reduce gastroesophageal reflux: new insights using multichannel intraluminal impedance technology". Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 8 (7): 890–7; discussion 897–8. November 2004. doi:10.1016/j.gassur.2004.08.001. PMID 15531244.

- ↑ "Physical and pH properties of gastroesophagopharyngeal refluxate: a 24-hour simultaneous ambulatory impedance and pH monitoring study". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 99 (6): 1000–10. June 2004. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30349.x. PMID 15180717.

- ↑ "Gastroesophageal and pharyngeal reflux detection using impedance and 24-hour pH monitoring in asymptomatic subjects: defining the normal environment". Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 10 (1): 54–62. January 2006. doi:10.1016/j.gassur.2005.09.005. PMID 16368491.

- ↑ "Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy: a multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring". Gut 55 (10): 1398–402. October 2006. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.087668. PMID 16556669.

- ↑ "Receptor-mediated uptake of pepsin by laryngeal epithelial cells". The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology 116 (12): 934–8. December 2007. doi:10.1177/000348940711601211. PMID 18217514.

- ↑ "Rationale for targeting pepsin in the treatment of reflux disease". The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology 119 (8): 547–58. August 2010. doi:10.1177/000348941011900808. PMID 20860281.

- ↑ "Pepsin as a causal agent of inflammation during nonacidic reflux". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 141 (5): 559–63. November 2009. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2009.08.022. PMID 19861190.

- ↑ "Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow?". Lancet 357 (9255): 539–45. February 2001. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. PMID 11229684.

- ↑ "Acid/pepsin promotion of carcinogenesis in the hamster cheek pouch". Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 126 (3): 405–9. March 2000. doi:10.1001/archotol.126.3.405. PMID 10722017.

- ↑ "Sensitive pepsin immunoassay for detection of laryngopharyngeal reflux". The Laryngoscope 115 (8): 1473–8. August 2005. doi:10.1097/01.mlg.0000172043.51871.d9. PMID 16094128.

- ↑ "Pepsin as a marker of extraesophageal reflux". The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology 119 (3): 203–8. March 2010. doi:10.1177/000348941011900310. PMID 20392035.

- ↑ "Reflux revisited: advancing the role of pepsin". International Journal of Otolaryngology 2012: 646901. 2012. doi:10.1155/2012/646901. PMID 22242022.

- ↑ "Pepstatin Inhibition Mechanism". Acid Proteases: Structure, Function, and Biology. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 95. 1977. pp. 199–210. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-0719-9_12. ISBN 978-1-4757-0721-2.

- ↑ "Bifunctional inhibitors of pepsin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 68 (11): 2765–8. November 1971. doi:10.1073/pnas.68.11.2765. PMID 4941985. Bibcode: 1971PNAS...68.2765H.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "Structural basis for the inhibition of porcine pepsin by Ascaris pepsin inhibitor-3". Nature Structural Biology 7 (8): 653–7. August 2000. doi:10.1038/77950. PMID 10932249.

- ↑ "The story of the isolation of crystalline pepsin and trypsin". The Scientific Monthly 35 (4): 333–340. 1932. Bibcode: 1932SciMo..35..333N.

- ↑ "The inhibition of pepsin-catalysed reactions by products and product analogues. Kinetic evidence for ordered release of products". The Biochemical Journal 113 (2): 363–8. June 1969. doi:10.1042/bj1130363. PMID 4897199.

- ↑ "Inhibition of peptic activity by sucralfate". The American Journal of Medicine 79 (2C): 15–8. August 1985. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(85)90566-2. PMID 3929601.

- ↑ Kun, Lee Yuan (2006). Microbial Biotechnology: Principles And Applications (2nd ed.). Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 981-256-677-5.

- ↑ Billings HJ, "Fortified Cereal", US patent 2259543, published 1938, assigned to Cream of Wheat Corporation

- ↑ "Gelatinase and the Gates-Gilman-Cowgill Method of Pepsin Estimation". The Journal of General Physiology 17 (1): 35–40. September 1933. doi:10.1085/jgp.17.1.35. PMID 19872760.

- ↑ "Anti-Hinge Antibodies Recognize IgG Subclass- and Protease-Restricted Neoepitopes". Journal of Immunology 198 (1): 82–93. January 2017. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1601096. PMID 27864476.

- ↑ Lane, David Stuart; Harlow, Edward (1988). Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. pp. A2926. ISBN 0-87969-314-2.

- ↑ "Pepsin". Merck KGaA. http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/life-science/metabolomics/enzyme-explorer/analytical-enzymes/pepsin.html.

External links

- The MEROPS online database for peptidases and their inhibitors: Pepsin A A01.001, Pepsin B A01.002, Pepsin C (Gastricsin) A01.003

- Pepsin+A at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Pepsinogens at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Pepsinogen+A at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Pepsinogen+C at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Beemans Gum

- Pepsin: Molecule of the Month , by David Goodsell, RCSB Protein Data Bank

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P20142 (Human Gastricsin) at the PDBe-KB.

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P0DJD7 (Pepsin A-4) at the PDBe-KB.

|