Chemistry:Arginine

Skeletal formula of arginine

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC names

Arginine

| |||

| Other names

2-Amino-5-guanidinopentanoic acid

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 3DMet |

| ||

| 1725411, 1725412 D, 1725413 L | |||

| ChEBI |

| ||

| ChEMBL |

| ||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank |

| ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 364938 D | |||

| |||

| KEGG |

| ||

| MeSH | Arginine | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII |

| ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C6H14N4O2 | |||

| Molar mass | 174.204 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | White crystals | ||

| Odor | Odourless | ||

| Melting point | 260 °C; 500 °F; 533 K | ||

| Boiling point | 368 °C (694 °F; 641 K) | ||

| 14.87 g/100 mL (20 °C) | |||

| Solubility | slightly soluble in ethanol insoluble in ethyl ether | ||

| log P | −1.652 | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.18 (carboxyl), 9.09 (amino), 13.8 (guanidino) | ||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

232.8 J K−1 mol−1 (at 23.7 °C) | ||

Std molar

entropy (S |

250.6 J K−1 mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−624.9–−622.3 kJ mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−3.7396–−3.7370 MJ mol−1 | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

| 1=ATC code }} | B05XB01 (WHO) S | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Safety data sheet | L-Arginine | ||

| GHS pictograms |

| ||

| GHS Signal word | WARNING | ||

| H319 | |||

| P305+351+338 | |||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

5110 mg/kg (rat, oral) | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related alkanoic acids

|

|||

Related compounds

|

|||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

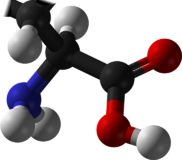

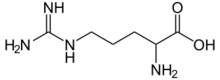

Arginine is the amino acid with the formula (H2N)(HN)CN(H)(CH2)3CH(NH2)CO2H. The molecule features a guanidino group appended to a standard amino acid framework. At physiological pH, the carboxylic acid is deprotonated (−CO2−) and both the amino and guanidino groups are protonated, resulting in a cation. Only the l-arginine (symbol Arg or R) enantiomer is found naturally.[1] Arg residues are common components of proteins. It is encoded by the codons CGU, CGC, CGA, CGG, AGA, and AGG.[2] The guanidine group in arginine is the precursor for the biosynthesis of nitric oxide.[3] Like all amino acids, it is a white, water-soluble solid.

History

Arginine was first isolated in 1886 from yellow lupin seedlings by the German chemist Ernst Schulze and his assistant Ernst Steiger.[4][5] He named it from the Greek árgyros (ἄργυρος) meaning "silver" due to the silver-white appearance of arginine nitrate crystals.[6] In 1897, Schulze and Ernst Winterstein (1865–1949) determined the structure of arginine.[7] Schulze and Winterstein synthesized arginine from ornithine and cyanamide in 1899,[8] but some doubts about arginine's structure lingered[9] until Sørensen's synthesis of 1910.[10]

Sources

Production

It is traditionally obtained by hydrolysis of various cheap sources of protein, such as gelatin.[11] It is obtained commercially by fermentation. In this way, 25-35 g/liter can be produced, using glucose as a carbon source.[12]

Dietary sources

Arginine is classified as a semiessential or conditionally essential amino acid, depending on the developmental stage and health status of the individual.[13] Preterm infants are unable to synthesize arginine internally, making the amino acid nutritionally essential for them.[14] Most healthy people do not need to supplement with arginine because it is a component of all protein-containing foods[15] and can be synthesized in the body from glutamine via citrulline.[16][17] Additional, dietary arginine is necessary for otherwise healthy individuals temporarily under physiological stress, for example during recovery from burns, injury or sepsis,[17] or if either of the major sites of arginine biosynthesis, the small intestine and kidneys, have reduced function, because the small bowel does the first step of the synthesizing process and the kidneys do the second.[3]

Arginine is an essential amino acid for birds, as they do not have a urea cycle.[18] For some carnivores, for example cats, dogs[19] and ferrets, arginine is essential,[3] because after a meal, their highly efficient protein catabolism produces large quantities of ammonia which need to be processed through the urea cycle, and if not enough arginine is present, the resulting ammonia toxicity can be lethal.[20] This is not a problem in practice, because meat contains sufficient arginine to avoid this situation.[20]

Animal sources of arginine include meat, dairy products, and eggs,[21][22] and plant sources include seeds of all types, for example grains, beans, and nuts.[22]

Biosynthesis

Arginine is synthesized from citrulline in the urea cycle by the sequential action of the cytosolic enzymes argininosuccinate synthetase and argininosuccinate lyase. This is an energetically costly process, because for each molecule of argininosuccinate that is synthesized, one molecule of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is hydrolyzed to adenosine monophosphate (AMP), consuming two ATP equivalents.

The pathways linking arginine, glutamine, and proline are bidirectional. Thus, the net use or production of these amino acids is highly dependent on cell type and developmental stage.

Arginine is made by the body as follows. The epithelial cells of the small intestine produce citrulline, primarily from glutamine and glutamate, which is secreted into the bloodstream which carries it to the proximal tubule cells of the kidney, which extract the citrulline and convert it to arginine, which is returned to the blood. This means that impaired small bowel or renal function can reduce arginine synthesis and thus create a dietary requirement for arginine. For such a person, arginine would become "essential".

Synthesis of arginine from citrulline also occurs at a low level in many other cells, and cellular capacity for arginine synthesis can be markedly increased under circumstances that increase the production of inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS). This allows citrulline, a byproduct of the NOS-catalyzed production of nitric oxide, to be recycled to arginine in a pathway known as the citrulline to nitric oxide (citrulline-NO) or arginine-citrulline pathway. This is demonstrated by the fact that, in many cell types, nitric oxide synthesis can be supported to some extent by citrulline, and not just by arginine. This recycling is not quantitative, however, because citrulline accumulates in nitric oxide producing cells along with nitrate and nitrite, the stable end-products of nitric oxide breakdown.[23]

Function

Arginine plays an important role in cell division, wound healing, removing ammonia from the body, immune function,[24] and the release of hormones.[13][25][26] It is a precursor for the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO),[27] making it important in the regulation of blood pressure.[28][29] Arginine is necessary for T-Cells to function in the body, and can lead to their deregulation if depleted.[30][31]

Proteins

Arginine's side chain is amphipathic, because at physiological pH it contains a positively charged guanidinium group, which is highly polar, at the end of a hydrophobic aliphatic hydrocarbon chain. Because globular proteins have hydrophobic interiors and hydrophilic surfaces,[32] arginine is typically found on the outside of the protein, where the hydrophilic head group can interact with the polar environment, for example taking part in hydrogen bonding and salt bridges.[33] For this reason, it is frequently found at the interface between two proteins.[34] The aliphatic part of the side chain sometimes remains below the surface of the protein.[33]

Arginine residues in proteins can be deiminated by PAD enzymes to form citrulline, in a post-translational modification process called citrullination.This is important in fetal development, is part of the normal immune process, as well as the control of gene expression, but is also significant in autoimmune diseases.[35] Another post-translational modification of arginine involves methylation by protein methyltransferases.[36]

Precursor

Arginine is the immediate precursor of nitric oxide, an important signaling molecule which can act as a second messenger, as well as an intercellular messenger which regulates vasodilation, and also has functions in the immune system's reaction to infection.

Arginine is also a precursor for urea, ornithine, and agmatine; is necessary for the synthesis of creatine; and can also be used for the synthesis of polyamines (mainly through ornithine and to a lesser degree through agmatine, citrulline, and glutamate). The presence of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), a close relative, inhibits the nitric oxide reaction; therefore, ADMA is considered a marker for vascular disease, just as L-arginine is considered a sign of a healthy endothelium.[37]

Structure

The amino acid side-chain of arginine consists of a 3-carbon aliphatic straight chain, the distal end of which is capped by a guanidinium group, which has a pKa of 13.8,[38] and is therefore always protonated and positively charged at physiological pH. Because of the conjugation between the double bond and the nitrogen lone pairs, the positive charge is delocalized, enabling the formation of multiple hydrogen bonds.

Research

Growth hormone

Intravenously administered arginine is used in growth hormone stimulation tests[39] because it stimulates the secretion of growth hormone.[40] A review of clinical trials concluded that oral arginine increases growth hormone, but decreases growth hormone secretion, which is normally associated with exercising.[41] However, a more recent trial reported that although oral arginine increased plasma levels of L-arginine it did not cause an increase in growth hormone.[42]

Herpes-Simplex Virus (Cold sores)

Research from 1964 into amino acid requirements of herpes simplex virus in human cells indicated that "...the lack of arginine or histidine, and possibly the presence of lysine, would interfere markedly with virus synthesis", but concludes that "no ready explanation is available for any of these observations".[43]

Further reviews conclude that "lysine's efficacy for herpes labialis may lie more in prevention than treatment." and that "the use of lysine for decreasing the severity or duration of outbreaks" is not supported, while further research is needed.[44] A 2017 study concludes that "clinicians could consider advising patients that there is a theoretical role of lysine supplementation in the prevention of herpes simplex sores but the research evidence is insufficient to back this. Patients with cardiovascular or gallbladder disease should be cautioned and warned of the theoretical risks."[45]

High blood pressure

A meta-analysis showed that L-arginine reduces blood pressure with pooled estimates of 5.4 mmHg for systolic blood pressure and 2.7 mmHg for diastolic blood pressure.[46]

Supplementation with l-arginine reduces diastolic blood pressure and lengthens pregnancy for women with gestational hypertension, including women with high blood pressure as part of pre-eclampsia. It did not lower systolic blood pressure or improve weight at birth.[47]

Schizophrenia

Both liquid chromatography and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometric assays have found that brain tissue of deceased people with schizophrenia shows altered arginine metabolism. Assays also confirmed significantly reduced levels of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), but increased agmatine concentration and glutamate/GABA ratio in the schizophrenia cases. Regression analysis indicated positive correlations between arginase activity and the age of disease onset and between L-ornithine level and the duration of illness. Moreover, cluster analyses revealed that L-arginine and its main metabolites L-citrulline, L-ornithine and agmatine formed distinct groups, which were altered in the schizophrenia group. Despite this, the biological basis of schizophrenia is still poorly understood, a number of factors, such as dopamine hyperfunction, glutamatergic hypofunction, GABAergic deficits, cholinergic system dysfunction, stress vulnerability and neurodevelopmental disruption, have been linked to the aetiology and/or pathophysiology of the disease.[48]

Raynaud's phenomenon

Oral L-arginine has been shown to reverse digital necrosis in Raynaud syndrome[49]

Safety and potential drug interactions

L-arginine is recognized as safe (GRAS-status) at intakes of up to 20 grams per day.[50] L-arginine is found in many foods, such as fish, poultry, and dairy products, and is used as a dietary supplement.[51] It may interact with various prescription drugs and herbal supplements.[51]

See also

- Arginine glutamate

- AAKG

- Canavanine and canaline are toxic analogs of arginine and ornithine.

References

- ↑ "Nomenclature and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides". IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature. 1983. http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iupac/AminoAcid/AA1n2.html.

- ↑ IUPAC-IUBMB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature. "Nomenclature and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides". Recommendations on Organic & Biochemical Nomenclature, Symbols & Terminology etc. http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iupac/AminoAcid/.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 (in en) Nitric Oxide: Biology and Pathobiology. Academic Press. 2000-09-13. pp. 189. ISBN 978-0-08-052503-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=h5FugARr4bgC&pg=PA189.

- ↑ "Biographie von Ernst Schulze". July 2015. http://www.arginium.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Biographie-Ernst-Schulze-Juli-2015.pdf.

- ↑ "Ueber das Arginin". Zeitschrift für Physiologische Chemie 11 (1–2): 43–65. 1887. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924078260597;view=1up;seq=55.

- ↑ "BIOETYMOLOGY: ORIGIN IN BIO-MEDICAL TERMS: arginine (Arg R)". https://bioetymology.blogspot.com/2012/03/arginin-arg-r.html.

- ↑ "Ueber ein Spaltungs-product des Arginins" (in de). Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft 30 (3): 2879–2882. September 1897. doi:10.1002/cber.18970300389. https://zenodo.org/record/1684244. The structure for arginine is presented on p. 2882.

- ↑ "Ueber die Constitution des Arginins" (in de). Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft 32 (3): 3191–3194. October 1899. doi:10.1002/cber.18990320385. https://zenodo.org/record/1617372.

- ↑ Organic Chemistry for Advanced Students, Part 3 (2nd ed.). New York, New York, USA: Longmans, Green & Co.. 1919. p. 140. https://books.google.com/books?id=NW3SAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA140.

- ↑ "Über die Synthese des dl-Arginins (α-Amino-δ-guanido-n-valeriansäure) und der isomeren α-Guanido-δ-amino-n-valeriansäure" (in de). Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft 43 (1): 643–651. January 1910. doi:10.1002/cber.191004301109. https://zenodo.org/record/2450981.

- ↑ "d-Arginine Hydrochloride". Org. Synth. 12: 4. 1932. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.012.0004.

- ↑ Drauz, Karlheinz; Grayson, Ian; Kleemann, Axel; Krimmer, Hans-Peter; Leuchtenberger, Wolfgang; Weckbecker, Christoph (2006). "Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a02_057.pub2.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "L-Arginine". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 56 (9): 439–445. November 2002. doi:10.1016/s0753-3322(02)00284-6. PMID 12481980.

- ↑ "Arginine deficiency in preterm infants: biochemical mechanisms and nutritional implications". The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 15 (8): 442–51. August 2004. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2003.11.010. PMID 15302078.

- ↑ "Drugs and Supplements Arginine". http://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/arginine/background/hrb-20058733.

- ↑ (in en) Dietitian's Handbook of Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 1998. pp. 76. ISBN 978-0-8342-0920-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=3qexy5Se3SoC&pg=PA76.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 (in en) Enteral Nutrition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 1994. pp. 48. ISBN 978-0-412-98471-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=1nRbFrSil40C&pg=PA48.

- ↑ (in en) A Biochemical Approach to Nutrition. Springer Science & Business Media. 2012-12-06. pp. 45. ISBN 9789400957329. https://books.google.com/books?id=dFb7AwAAQBAJ&pg=PA45.

- ↑ (in en) Nutrient Requirements of Dogs. National Academies Press. 1985. pp. 65. ISBN 978-0-309-03496-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=LWC6PChg9ZEC&pg=PA65.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 (in en) Nutrition and Disease Management for Veterinary Technicians and Nurses. John Wiley & Sons. 2015-06-11. pp. 232. ISBN 978-1-118-81108-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=mh7yCQAAQBAJ&pg=PA232.

- ↑ (in en) Nutrition for Sport, Exercise, and Health. Human Kinetics. 2017-08-30. pp. 240. ISBN 978-1-4504-1487-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=p_YtDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA240.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 (in en) Bioactive Dietary Factors and Plant Extracts in Dermatology. Springer Science & Business Media. 2012-11-28. pp. 75. ISBN 978-1-62703-167-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=kzKqMAkJw3UC&pg=PA75.

- ↑ "Enzymes of arginine metabolism". The Journal of Nutrition 134 (10 Suppl): 2743S–2747S; discussion 2765S–2767S. October 2004. doi:10.1093/jn/134.10.2743S. PMID 15465778.

- ↑ (in en) The Metabolic Challenges of Immune Cells in Health and Disease. Frontiers Media SA. 2015-07-13. pp. 17. ISBN 9782889196227. https://books.google.com/books?id=Hc3rCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA17.

- ↑ "Arginine supplementation and wound healing". Nutrition in Clinical Practice 20 (1): 52–61. February 2005. doi:10.1177/011542650502000152. PMID 16207646.

- ↑ "Arginine physiology and its implication for wound healing". Wound Repair and Regeneration 11 (6): 419–23. 2003. doi:10.1046/j.1524-475X.2003.11605.x. PMID 14617280.

- ↑ "Enzymatic function of nitric oxide synthases". Cardiovascular Research 43 (3): 521–31. August 1999. doi:10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00115-7. PMID 10690324.

- ↑ "L-arginine and hypertension". The Journal of Nutrition 134 (10 Suppl): 2807S–2811S; discussion 2818S–2819S. October 2004. doi:10.1093/jn/134.10.2807S. PMID 15465790.

- ↑ "Upregulation of colonic luminal polyamines produced by intestinal microbiota delays senescence in mice". Scientific Reports 4 (4548): 4548. 2014. doi:10.1038/srep04548. PMID 24686447. Bibcode: 2014NatSR...4E4548K.

- ↑ Banerjee, Kasturi; Chattopadhyay, Agnibha; Banerjee, Satarupa (2022-07-01). "Understanding the association of stem cells in fetal development and carcinogenesis during pregnancy" (in en). Advances in Cancer Biology - Metastasis 4: 100042. doi:10.1016/j.adcanc.2022.100042. ISSN 2667-3940.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Paulo C.; Quiceno, David G.; Ochoa, Augusto C. (2006-10-05). "l-arginine availability regulates T-lymphocyte cell-cycle progression". Blood 109 (4): 1568–1573. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-06-031856. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 17023580. PMC 1794048. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2006-06-031856.

- ↑ Biochemistry (3rd ed.). San Francisco, Calif.: Benjamin Cummings. 2000. pp. 180. ISBN 978-0805330663. OCLC 42290721. https://archive.org/details/biochemistry0003math.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Bioinformatics for Geneticists: A Bioinformatics Primer for the Analysis of Genetic Data. John Wiley & Sons. 2007-04-16. pp. 326. ISBN 9780470026199. https://books.google.com/books?id=CN9sYPJdXs4C&pg=PA326.

- ↑ (in en) Protein-protein Recognition. Oxford University Press. 2000. pp. 13. ISBN 9780199637607. https://books.google.com/books?id=hbd8dlG7zkIC&pg=PA13.

- ↑ Griffiths & Unwin 2016, p. 275.

- ↑ Griffiths & Unwin 2016, p. 176.

- ↑ "Arginine and Endothelial Function". Biomedicines 8 (8): 277. August 2020. doi:10.3390/biomedicines8080277. PMID 32781796.

- ↑ "Arginine: Its pKa value revisited". Protein Science 24 (5): 752–61. May 2015. doi:10.1002/pro.2647. PMID 25808204.

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Growth hormone stimulation test

- ↑ "Arginine stimulates growth hormone secretion by suppressing endogenous somatostatin secretion". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 67 (6): 1186–9. December 1988. doi:10.1210/jcem-67-6-1186. PMID 2903866.

- ↑ "Growth hormone, arginine and exercise". Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 11 (1): 50–4. January 2008. doi:10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f2b0ad. PMID 18090659.

- ↑ "The acute effects of a low and high dose of oral L-arginine supplementation in young active males at rest". Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 36 (3): 405–11. June 2011. doi:10.1139/h11-035. PMID 21574873.

- ↑ "Amino Acid Requirements of Herpes Simplex Virus in Human Cells". Journal of Bacteriology 87 (3): 609–613. March 1964. doi:10.1128/jb.87.3.609-613.1964. PMID 14127578.

- ↑ "Lysine for management of herpes labialis". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 58 (4): 298–300, 304. February 2001. doi:10.1093/ajhp/58.4.298. PMID 11225166.

- ↑ "Lysine for Herpes Simplex Prophylaxis: A Review of the Evidence". Integrative Medicine 16 (3): 42–46. June 2017. PMID 30881246.

- ↑ "Effect of oral L-arginine supplementation on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials". American Heart Journal 162 (6): 959–65. December 2011. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.012. PMID 22137067.

- ↑ "Arginine supplementation for improving maternal and neonatal outcomes in hypertensive disorder of pregnancy: a systematic review". Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System 15 (1): 88–96. March 2014. doi:10.1177/1470320313475910. PMID 23435582.

- ↑ "Altered brain arginine metabolism in schizophrenia". Translational Psychiatry 6 (8): e871. August 2016. doi:10.1038/tp.2016.144. PMID 27529679.

- ↑ Rembold, Christopher M.; Ayers, Carlos R. (February 2003). "Oral L-arginine can reverse digital necrosis in Raynaud's phenomenon". Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 244 (1–2): 139–141. doi:10.1023/A:1022422932108. ISSN 0300-8177. PMID 12701823. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12701823/.

- ↑ "Risk assessment for the amino acids taurine, L-glutamine and L-arginine". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 50 (3): 376–99. April 2008. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2008.01.004. PMID 18325648.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 "L-Arginine" (in en). MedlinePlus, US National Institutes of Health. 13 October 2021. https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/natural/875.html.

Sources

- Analysis of Protein Post-Translational Modifications by Mass Spectrometry. John Wiley & Sons. 2016. ISBN 978-1-119-25088-3.

External links

|