Biology:Singing vole

| Singing vole | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Cricetidae |

| Subfamily: | Arvicolinae |

| Genus: | Microtus |

| Species: | M. miurus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Microtus miurus Osgood, 1901

| |

| Subspecies | |

|

See text | |

| |

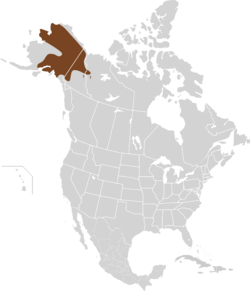

The singing vole (Microtus miurus), is a medium-sized vole found in northwestern North America, including Alaska and northwestern Canada .[2]

Physical characteristics

Singing voles have short ears, often concealed by their long fur, and a short tail. The fur is soft and dense, especially in winter. They vary in color from pale tawny to pale grey, with buff-colored patches running from the undersides of the ears along the flanks to the rump, and buff or ochre underparts. The fur is lightly ticked with black guard hairs, but these are so sparse that have little effect on the visible coloration of the animal. The fur is greyer in color during the winter. The paws have sharp, narrow claws, which are largely hidden by fur.[3]

Adult singing voles range from 9 to 16 centimetres (3.5 to 6.3 in) in length, not counting the short, 1.5 to 4 centimetres (0.59 to 1.57 in), tail. They can weigh anything from 11 to 60 grams (0.39 to 2.12 oz), depending on their exact age and recent diet. There is no significant difference in size or coloration between the two sexes. Male singing voles possess modified sebaceous glands on their flanks, which are used in scent marking; these glands have also been noted in some lactating females. The penis is relatively long and narrow, with a complex baculum.[3]

Singing voles can be distinguished from other neighboring vole species by their shorter tails and the color of their underparts (other local voles have grey underparts).

Distribution and habitat

Singing voles are native to Alaska and north-western Canada. They are found from the western coasts, across southern and northern Alaska, but avoid the Alaska Peninsula, the central regions, and much of the northern coast. In the east, they reach as far as the Mackenzie Mountains, being found throughout the Yukon, aside from the northern coasts, and in border regions of the neighboring provinces.[3]

Four subspecies are currently recognised:

- Microtus miurus miurus - Kenai Peninsula

- Microtus miurus cantator - south-eastern Alaska and southern Yukon

- Microtus miurus miuriei - south-western Alaska

- Microtus miurus oreas - northern Alaska and Yukon

Singing voles are found in tundra regions above the tree line. They avoid the most extreme environments within these regions, preferring open, well-drained slopes and rock flats with abundant shrubs and sedges. They feed on arctic plants such as lupines, knotweed, sedges, horsetails, and willows. Their main predators include wolverines, Arctic foxes, stoats, skuas, hawks, and owls.[3]

Behavior

Singing voles are at least semi-colonial animals, sharing burrows between family groups. They are active throughout the day, with no clear preference for sunlight or night time. They make runways through the surface growth, connecting feeding grounds to burrow entrances, although these are not as clear as those made by some other vole species. They also sometimes forage in low bushes.

The burrows consist of a number of chambers, many of them used to store food for the winter, connected by very narrow passages. These passages, typically around 2.5 centimetres (0.98 in) wide, make it difficult for any animal larger than a vole to pass through, and thus help protect against predators such as weasels. The burrows run horizontally, no more than 20 centimetres (7.9 in) below ground level, and can extend for as far as 1 metre (3.3 ft) from the tunnel entrance.[3]

Unusually among voles, in addition to storing food, such as roots and rhizomes, underground, singing voles also often leave stacks of grasses out on rocks to dry. Often, these stacks are instead constructed on low-lying branches, or on exposed tree roots, helping to keep them dry. The stacks of grasses slowly dry out, producing hay, and may include other food materials, such as horsetails or lupines. The voles begin to construct the stacks around August, and by the winter, they may have reached considerable size, with piles of up to 50 centimetres (20 in) in height having been reported. The piles are a source of nutritious food through the winter, although they are liable to be raided by other animals.[3]

This species gets its common name from its warning call, a high-pitched trill, usually given from the entrance of its burrow.[4]

Reproduction

Singing voles breed from May to September, and each female can give birth to up to three litters in a breeding season. Gestation lasts 21 days, and typically results in the birth of eight young, although litters of between 6 and 14 young have been reported.[3] Since, like other voles, the female has only eight teats, litters of more than eight young are unlikely to survive.

The young weigh 2 to 2.8 grams (0.071 to 0.099 oz) at birth, and grow rapidly during the first three weeks of life. They are weaned at around four weeks, by which time the mother is often ready to produce a new litter. Although females generally do not reproduce until their second year, males may be sexually active within as little as a month of birth.[3]

In the wild, many singing voles do not survive even their first winter. In captivity, they have been reported to live for up to 112 weeks, although the median lifespan is only 43 weeks.[5]

Evolution

The oldest known fossils of singing voles date from the Ionian, around 300,000 years ago, and were found near Fairbanks. During the Ice Ages of the late Pleistocene, singing voles may have been much more widely distributed than today, and fossils have been reported from as far south as Iowa, which was then probably similar in climate to present-day Alaska. The closest living relative of the Singing Vole today is the insular vole, which is found only on two small islands off the west coast of Alaska, and probably diverged as those islands were cut off from the Beringia land bridge by rising sea levels.[3]

References

- ↑ Linzey, A.V.; Hammerson, G. (NatureServe) (2008). "Microtus miurus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008. https://www.iucnredlist.org/details/42629/0/0. Retrieved 22 June 2009. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern.

- ↑ Musser, G. G. and M. D. Carleton. 2005. Superfamily Muroidea. Pp. 894-1531 in Mammal Species of the World a Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder eds. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 F.R. Cole; D.E. Wilson (2010). "Microtus miurus (Rodentia: Cricetidae)". Mammalian Species 42: 75–89. doi:10.1644/855.1.

- ↑ Bee J.W., Hall E.R. 1956. Mammals of northern Alaska on the Arctic Slope. Miscellaneous Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas. 8:1–309.

- ↑ Morrison P., Dieterich R., Preston D. 1977b. Longevity and mortality in 15 rodent species and subspecies maintained in laboratory colonies. Acta Theriologica. 22:317–335

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q1761683 entry

|