Complex-base system

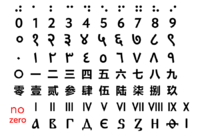

| Numeral systems |

|---|

|

| Hindu–Arabic numeral system |

| East Asian |

| Alphabetic |

| Former |

| Positional systems by base |

| Non-standard positional numeral systems |

| List of numeral systems |

In arithmetic, a complex-base system is a positional numeral system whose radix is an imaginary (proposed by Donald Knuth in 1955[1][2]) or complex number (proposed by S. Khmelnik in 1964[3] and Walter F. Penney in 1965[4][5][6]).

In general

Let be an integral domain , and the (Archimedean) absolute value on it.

A number in a positional number system is represented as an expansion

where

is the radix (or base) with , is the exponent (position or place), are digits from the finite set of digits , usually with

The cardinality is called the level of decomposition.

A positional number system or coding system is a pair

with radix and set of digits , and we write the standard set of digits with digits as

Desirable are coding systems with the features:

- Every number in , e. g. the integers , the Gaussian integers or the integers , is uniquely representable as a finite code, possibly with a sign ±.

- Every number in the field of fractions , which possibly is completed for the metric given by yielding or , is representable as an infinite series which converges under for , and the measure of the set of numbers with more than one representation is 0. The latter requires that the set be minimal, i.e. for real numbers and for complex numbers.

In the real numbers

In this notation our standard decimal coding scheme is denoted by

the standard binary system is

the negabinary system is

and the balanced ternary system[2] is

All these coding systems have the mentioned features for and , and the last two do not require a sign.

In the complex numbers

Well-known positional number systems for the complex numbers include the following ( being the imaginary unit):

- , e.g. [1] and

- ,[2] the quater-imaginary base, proposed by Donald Knuth in 1955.

- and

- , where , and is a positive integer that can take multiple values at a given .[7] For and this is the system

- .[8]

- , where the set consists of complex numbers , and numbers , e.g.

- , where [9]

Binary systems

Binary coding systems of complex numbers, i.e. systems with the digits , are of practical interest.[9] Listed below are some coding systems (all are special cases of the systems above) and resp. codes for the (decimal) numbers −1, 2, −2, i. The standard binary (which requires a sign, first line) and the "negabinary" systems (second line) are also listed for comparison. They do not have a genuine expansion for i.

| Radix | –1 ← | 2 ← | –2 ← | i ← | Twins and triplets | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | –1 | 10 | –10 | i | 1 ← | 0.1 = 1.0 |

| –2 | 11 | 110 | 10 | i | 1/3 ← | 0.01 = 1.10 |

| 101 | 10100 | 100 | 10.101010100...[11] | ← | 0.0011 = 11.1100 | |

| 111 | 1010 | 110 | 11.110001100...[11] | ← | 1.011 = 11.101 = 11100.110 | |

| 101 | 10100 | 100 | 10 | 1/3 + 1/3i ← | 0.0011 = 11.1100 | |

| –1+i | 11101 | 1100 | 11100 | 11 | 1/5 + 3/5i ← | 0.010 = 11.001 = 1110.100 |

| 2i | 103 | 2 | 102 | 10.2 | 1/5 + 2/5i ← | 0.0033 = 1.3003 = 10.0330 = 11.3300 |

As in all positional number systems with an Archimedean absolute value, there are some numbers with multiple representations. Examples of such numbers are shown in the right column of the table. All of them are repeating fractions with the repetend marked by a horizontal line above it.

If the set of digits is minimal, the set of such numbers has a measure of 0. This is the case with all the mentioned coding systems.

The almost binary quater-imaginary system is listed in the bottom line for comparison purposes. There, real and imaginary part interleave each other.

Base −1 ± i

Of particular interest are the quater-imaginary base (base 2i) and the base −1 ± i systems discussed below, both of which can be used to finitely represent the Gaussian integers without sign.

Base −1 ± i, using digits 0 and 1, was proposed by S. Khmelnik in 1964[3] and Walter F. Penney in 1965.[4][6]

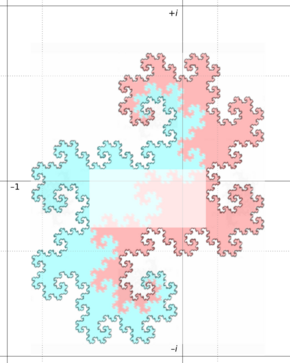

Connection to the twindragon

The rounding region of an integer – i.e., a set of complex (non-integer) numbers that share the integer part of their representation in this system – has in the complex plane a fractal shape: the twindragon (see figure). This set is, by definition, all points that can be written as with . can be decomposed into 16 pieces congruent to . Notice that if is rotated counterclockwise by 135°, we obtain two adjacent sets congruent to , because . The rectangle in the center intersects the coordinate axes counterclockwise at the following points: , , and , and . Thus, contains all complex numbers with absolute value ≤ 1/15.[12]

As a consequence, there is an injection of the complex rectangle

into the interval of real numbers by mapping

with .[13]

Furthermore, there are the two mappings

and

both surjective, which give rise to a surjective (thus space-filling) mapping

which, however, is not continuous and thus not a space-filling curve. But a very close relative, the Davis-Knuth dragon, is continuous and a space-filling curve.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Knuth, D.E. (1960). "An Imaginary Number System". Communications of the ACM 3 (4): 245–247. doi:10.1145/367177.367233.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Knuth, Donald (1998). "Positional Number Systems". The art of computer programming. 2 (3rd ed.). Boston: Addison-Wesley. pp. 205. ISBN 0-201-89684-2. OCLC 48246681.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Khmelnik, S.I. (1964). "Specialized digital computer for operations with complex numbers". Questions of Radio Electronics (In Russian) XII (2).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 W. Penney, A "binary" system for complex numbers, JACM 12 (1965) 247-248.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Jamil, T. (2002). "The complex binary number system". IEEE Potentials 20 (5): 39–41. doi:10.1109/45.983342.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Duda, Jarek (2008-02-24). "Complex base numeral systems". arXiv:0712.1309 [math.DS].

- ↑ Khmelnik, S.I. (1966). "Positional coding of complex numbers". Questions of Radio Electronics (In Russian) XII (9).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Khmelnik, S.I. (2004). Coding of Complex Numbers and Vectors (in Russian). Israel: Mathematics in Computer. ISBN 978-0-557-74692-7. http://mic34.com/Magazine/94846.pdf.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Khmelnik, S.I. (2001). Method and system for processing complex numbers. Patent USA, US2003154226 (A1). http://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/biblio?DB=EPODOC&adjacent=true&locale=en_EP&FT=D&date=20030814&CC=US&NR=2003154226A1&KC=A1.

- ↑ William J. Gilbert, "Arithmetic in Complex Bases" Mathematics Magazine Vol. 57, No. 2, March 1984

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 infinite non-repeating sequence

- ↑ Knuth 1998 p.206

- ↑ Base cannot be taken because both, and . However, is unequal to .

External links

- "Number Systems Using a Complex Base" by Jarek Duda, the Wolfram Demonstrations Project

- "The Boundary of Periodic Iterated Function Systems" by Jarek Duda, the Wolfram Demonstrations Project

- "Number Systems in 3D" by Jarek Duda, the Wolfram Demonstrations Project

- "Large introduction to complex base numeral systems" with Mathematica sources by Jarek Duda

|