Engineering:Huolongjing

The Huolongjing (traditional Chinese: 火龍經; simplified Chinese: 火龙经; pinyin: Huǒ Lóng Jīng; Wade-Giles: Huo Lung Ching; rendered in English as Fire Drake Manual or Fire Dragon Manual), also known as Huoqitu (“Firearm Illustrations”), is a Chinese military treatise compiled and edited by Jiao Yu and Liu Bowen of the early Ming dynasty (1368–1683) during the 14th century. The Huolongjing is primarily based on the text known as Huolong Shenqi Tufa (Illustrations of Divine Fire Dragon Engines), which no longer exists.[1]

History

The Huolongjing's intended function was to serve as a guide to "fire weapons" involving gunpowder during the 1280s to 1350s.[2] Its predecessor, the Huolong Shenqi Tufa (Fire-Drake Illustrated Technology of Magically (Efficacious) Weapons), has since been lost. The Huolongjing was one of three early Ming military treatises that were mentioned by Jiao Xu, but only the Huolongjing remains.[3]

Although the earliest edition of the Huolongjing was written by Jiao Yu, a Ming general, sometime between 1360-1375,[4] its preface was not provided until the Nanyang publication of 1412. The 1412 edition, known as Huolongjing Quanji (Complete Collection of the Fire Dragon Manual), remains largely unchanged from its predecessor with the exception of its preface, which provides an account of Jiao Yu's time in the Hongwu Emperor's army. In the preface Jiao Yu claims to describe gunpowder weapons that had seen use since 1355 during his involvement in the Red Turban Rebellion and revolt against the Yuan dynasty, while the oldest material found in his text dates to 1280. Jiao Yu was a firearm manufacturer for the first Ming emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang, during the mid-14th century. He was eventually put in charge of the Shenjiying armoury where all the firearms were stored.[5]

A second and third volume to the Huolongjing known as Huolongjing Erji (Fire Dragon Manual Volume Two) and Huolongjing Sanji (Fire Dragon Manual Volume Three) were published in 1632 with content describing weapons such as the musket and breech-loading cannons.[6] After the end of the Ming dynasty, the Qing dynasty outlawed reprinting of the Huolongjing for using expressions such as 'northern barbarians,' which offended the ruling Manchu elite.[2]

Contents

Gunpowder and explosives

Although its destructive force was widely recognized by the 11th century, gunpowder continued to be known as a "fire-drug" (huo yao) because of its original intended pharmaceutical properties.[7] However soon after the chemical formula for gunpowder was recorded in the Wujing Zongyao of 1044,[8][9] evidence of state interference in gunpowder affairs began appearing. Realizing the military applications of gunpowder, the Song court banned private transactions involving sulphur and saltpeter in 1067 despite the widespread use of saltpeter as a flavor enhancer,[10] and moved to monopolize gunpowder production.[11] In 1076 the Song prohibited the populaces of Hedong (Shanxi) and Hebei from selling sulphur and saltpetre to foreigners.[12][13] In 1132 gunpowder was referred to specifically for its military values for the first time and was called "fire bomb medicine" rather than "fire medicine".[14]

While Chinese gunpowder formulas by the late 12th century and at least 1230 were powerful enough for explosive detonations and bursting cast iron shells,[8] gunpowder was made more potent by applying the enrichment of sulphur from pyrite extracts.[15] Chinese gunpowder solutions reached maximum explosive potential in the 14th century and at least six formulas are considered to have been optimal for creating explosive gunpowder, with levels of nitrate ranging from 12% to 91%.[16] Evidence of large scale explosive gunpowder weapons manufacturing began to appear. While engaged in war with the Mongols in 1259, the official Li Zengbo wrote in his Ko Zhai Za Gao, Xu Gao Hou that the city of Qingzhou was manufacturing one to two thousand strong iron-cased bomb shells a month, and delivered them to Xiangyang and Yingzhou in loads of about ten to twenty thousand shells at a time.[17]

The Huolongjing's primary contribution to gunpowder was in expanding its role as a chemical weapon. Jiao Yu proposed several gunpowder compositions in addition to the standard potassium nitrate (saltpetre), sulphur, and charcoal. Described are the military applications of "divine gunpowder", "poison gunpowder", and "blinding and burning gunpowder."[18] Poisonous gunpowder for hand-thrown or trebuchet launched bombs[19] was created using a mixture of tung oil, urine, sal ammoniac, feces, and scallion juice heated and coated upon tiny iron pellets and broken porcelain.[20] According to Jiao Yu, "even birds flying in the air cannot escape the effects of the explosion".[20]

Explosive devices include the "flying-sand divine bomb releasing ten thousand fires", which consisted of a tube of gunpowder placed in an earthenware pot filled with quicklime, resin, and alcoholic extracts of poisonous plants.[21]

Fire arrows and rockets

Jiao Yu called the earliest fire arrows shot from bows (not rocket launchers) "fiery pomegranate shot from a bow" because the lump of gunpowder–filled paper wrapped around the arrow below the metal arrowhead resembled the shape of a pomegranate.[22] He advised that a piece of hemp cloth should be used to strengthen the wad of paper and sealed with molten pine resin.[23] Although he described the fire arrow in great detail, it was mentioned by the much earlier Xia Shaozeng, when 20,000 fire arrows were handed over to the Jurchen conquerors of Kaifeng City in 1126.[23] An even earlier text, the Wujing Zongyao (武经总要, "Collection of the Most Important Military Techniques"), written in 1044 by Song scholars Zeng Gongliang and Yang Weide, described the use of three spring or triple bow arcuballista that fired arrow bolts holding gunpowder.[23] Although written in 1630 (second edition in 1664), the Wulixiaoshi of Fang Yizhi said that fire arrows were presented to Emperor Taizu of Song in 960.[24] Even after the rocket was invented in China the fire arrow was never entirely phased out: it saw use in the Second Opium War when Chinese used fire arrows against the French in 1860.[25]

By the time of Jiao Yu, the term "fire arrow" had taken on a new meaning and also referred to the earliest rockets found in China.[19][26] The simple transition of this was to use a hollow tube instead of a bow or ballista firing gunpowder-impregnated fire arrows. The historian Joseph Needham wrote that this discovery came sometime before Jiao Yu during the late Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279).[26] From the section of the oldest passages in the Huolongjing,[26] the text reads:

One uses a bamboo stick 4 ft 2 in long, with an iron (or steel) arrow–head 4.5 in long...behind the feathering there is an iron weight 0.4 in long. At the front end there is a carton tube bound on to the stick, where the 'rising gunpowder' is lit. When you want to fire it off, you use a frame shaped like a dragon, or else conveniently a tube of wood or bamboo to contain it.[26]

In the late 14th century, the rocket launching tube was combined with the fire lance.[27] This involved three tubes attached to the same staff. As the first rocket tube was fired, a charge was ignited in the leading tube which expelled a blinding lachrymatory powder at the enemy, and finally the second rocket was fired.[27] An illustration of this appears in the Huolongjing, and a description of its effectiveness in obfuscating the location of the rockets from the enemy is provided.[27] The Huolongjing also describes and illustrates two kinds of mounted rocket launchers that fired multiple rockets.[28] There was a cylindrical, basket-work rocket launcher called the "Mr. Facing-both-ways rocket arrow firing basket", as well as an oblong-section, rectangular, box rocket launcher known as the "divine rocket-arrow block".[29] Rockets described in the Huolongjing were not all in the shape of standard fire arrows and some had artificial wings attached.[30][31] An illustration shows that fins were used to increase aerodynamic stability for the flight path of the rocket,[31][32] which according to Jiao Yu could rise hundreds of feet before landing at the designated enemy target.[31][33]

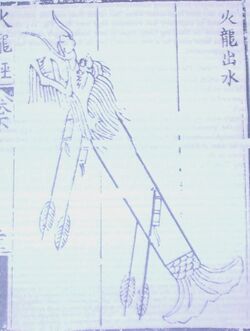

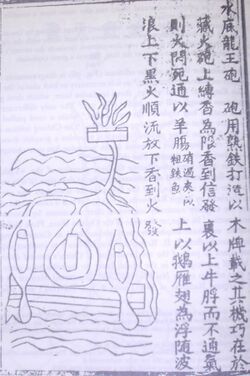

The Huolongjing also describes and illustrates the oldest known multistage rocket; this was the "fire-dragon issuing from the water" (huo long chu shui), which was known to be used by the Chinese navy.[34][35] It was a two-stage rocket that had carrier or booster rockets that would automatically ignite a number of smaller rocket arrows that were shot out of the front end of the missile, which was shaped like a dragon's head with an open mouth, before eventually burning out.[34][35] This multistage rocket is considered by some historians to be the ancestor of modern cluster munitions.[34][35] Needham says that the written material and illustration of this rocket come from the oldest stratum of the Huolongjing, which can be dated to about 1300-1350 from the book's part 1, chapter 3, page 23.[34]

Fire lance

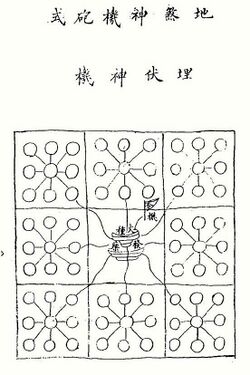

The fire lance or fire tube—a combination of a firearm and flamethrower[36]—had been adapted and changed into several different forms by the time Jiao Yu edited the Huolongjing.[37] The earliest depiction of a fire lance is dated c. 950, a Chinese painting on a silk banner found at the Buddhist site of Dunhuang.[38] These early fire lances were made of bamboo tubes, but metal barrels had appeared during the 13th century, and shot gunpowder flames along with "coviative" projectiles such as small porcelain shards or metal scraps.[39] The first metal barrels were not designed to withstand high-nitrate gunpowder and a bore-filling projectile; rather, they were designed for the low-nitrate flamethrower fire lance that shot small coviative missiles.[40] This was called the "bandit-striking penetrating gun" (ji zei bian chong).[40] Some of these low–nitrate gunpowder flamethrowers used poisonous mixtures such as arsenious oxide, and would blast a spray of porcelain shards as fragmentation.[41][19] Another fire lance described in the Huolongjing was called the 'lotus bunch' shot arrows accompanied by a fiery blast.[42] In addition to fire lances, the Huolongjing also illustrates a tall, vertical, mobile shield used to hide and protect infantry, known as the "mysteriously moving phalanx-breaking fierce-flame sword-shield".[43] This large, rectangular shield would have been mounted on wheels with five rows of six circular holes each where the fire lances could be placed. The shield itself would have been accompanied by swordsmen on either side to protect the gunmen.[43]

Bombards, cannons, and guns

In China, the first cannon-barrel design portrayed in artwork was a stone sculpture dated to 1128 found in Sichuan province.[44] The oldest extant cannon containing an inscription is a bronze cannon of China inscribed with the date, "2nd year of the Dade era, Yuan Dynasty" (1298). The oldest confirmed extant cannon is the Heilongjiang hand cannon, dated to 1288 using contextual evidence.[45] The History of Yuan records that in that year a rebellion of the Christian Mongol prince Nayan broke out and the Jurchen commander Li Ting who, along with a Korean brigade conscripted by Kublai Khan, suppressed Nayan's rebellion using hand cannons and portable bombards.[46]

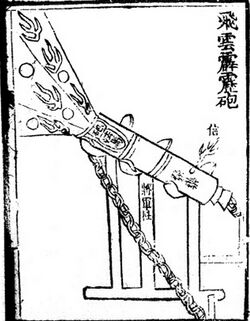

The predecessor of the metal barrel was made of bamboo, which was recorded in use by a Chinese garrison commander at Anlu, Hubei province, in the year 1132.[47] One of the earliest references to the destructive force of a cannon in China was made by Zhang Xian in 1341, with his verse known as The Iron Cannon Affair.[48] Zhang wrote that its cannonball could "pierce the heart or belly when it strikes a man or horse, and can even transfix several persons at once".[48] Jiao Yu describes the cannon, called the "eruptor", as a cast bronze device which had an average length of 53 inches (130 cm).[49] He wrote that some cannons were simply filled with about 100 lead balls, but others, called the "flying-cloud thunderclap eruptor" (飞云霹雳炮; feiyun pili pao) had large rounds that produced a bursting charge upon impact.[49] The ammunition consisted of hollow cast iron shells packed with gunpowder to create an explosive effect.[49] Also mentioned is a "poison-fog divine smoke eruptor," in which "blinding gunpowder" and "poisonous gunpowder" were packed into hollow shells used in burning the faces and eyes of enemies, along with choking them with a formidable spray of poisonous smoke.[50] Cannons were mounted on frames or on wheeled carriages so that they could be rotated to change directions.[51]

The Huolongjing also contains a hand held organ gun with up to ten barrels.[52] For the "match-holding lance gun" (chi huo–sheng qiang), it described its arrangement as a match brought down to the touch hole of three gun barrels, one after the other.[53] During the reign of the Yongle Emperor (1402–1424), the Shenjiying, a specialized military body, was in part a cavalry force that utilized tubes filled with inflammable materials holstered to their sides, and also a firearm infantry division that handled light artillery and their transportation, including the handling of gun carriages.[54]

Land mines and naval mines

The first recorded use of land mines occurred in 1277 when officer Lou Qianxia of the late Song Dynasty, who is credited with their invention, used them to kill Mongol soldiers.[55] Jiao Yu wrote that land mines were spherical, made of cast iron, and their fuses were ignited by the enemy movement disturbing a trigger mechanism.[56] Although his book did not elaborate on the trigger mechanism, it does mention the use of steel wheels as the trigger mechanism. The earliest illustration and description of the "steel wheel" mechanism was the Binglu of 1606. According to it, the steel wheel trigger mechanism utilized a pin release, dropping weights, cords and axles that worked to rotate a spinning "steel wheel" that rotated against a piece of flint to provide sparks that ignited the mines' fuses underground.[57]

The explosive mine is made of cast iron about the size of a rice-bowl, hollow inside with (black) powder rammed into it. A small bamboo tube is inserted and through this passes the fuse, while outside (the mine) a long fuse is led through fire-ducts. Pick a place where the enemy will have to pass through, dig pits and bury several dozen such mines in the ground. All the mines are connected by fuses through the gunpowder fire-ducts, and all originate from a steel wheel (gang lun). This must be well concealed from the enemy. On triggering the firing device the mines will explode, sending pieces of iron flying in all directions and shooting up flames towards the sky.[58]

For the use of naval mines, he wrote of slowly burning joss sticks that were disguised and timed to explode against enemy ships nearby:

The sea–mine called the 'submarine dragon–king' is made of wrought iron, and carried on a (submerged) wooden board, [appropriately weighted with stones]. The (mine) is enclosed in an ox-bladder. Its subtlety lies in the fact that a thin incense(–stick) is arranged (to float) above the mine in a container. The (burning) of this joss stick determines the time at which the fuse is ignited, but without air its glowing would of course go out, so the container is connected with the mine by a (long) piece of goat's intestine (through which passes the fuse). At the upper end the (joss stick in the container) is kept floating by (an arrangement of) goose and wild–duck feathers, so that it moves up and down with the ripples of the water. On a dark (night) the mine is sent downstream (towards the enemy's ships), and when the joss stick has burnt down to the fuse, there is a great explosion.[59]

In the later Tiangong Kaiwu (The Exploitation of the Works of Nature) treatise, written by Song Yingxing in 1637, the ox bladder described by Jiao Yu is replaced with a lacquer bag and a cord pulled from a hidden ambusher located on the nearby shore, which would release a flint steel–wheel firing mechanism to ignite the fuse of the naval mine.[60]

Legacy

Gunpowder warfare occurred in earnest during the Song dynasty. In China, gunpowder weapons underwent significant technological changes which resulted in a vast array of weapons that eventually led to the cannon. The cannon's first confirmed use occurred during the Mongol Yuan dynasty in a suppression of rebel forces by Yuan Jurchen forces armed with hand cannons. Cannon development continued into the Ming and saw greater proliferation during the Ming wars. Chinese cannon development reached internal maturity with the muzzle loading wrought iron "great general cannon" (大將軍炮), otherwise known by its heavier variant name "great divine cannon" (大神銃), which could weigh up to 600 kg (1,300 lb) and was capable of firing several iron balls and upward of a hundred iron shots at once. The lighter "great general cannon" weighed up to 360 kg (790 lb) and could fire a 4.8 kg (11 lb) lead ball. The great general and divine cannons were the last indigenous Chinese cannon designs prior to the incorporation of European models in the 16th century.[61]

When the Portuguese reached China in the early 16th century, they were unimpressed with Chinese firearms compared with their own.[62] With the progression of the earliest European arquebus to the matchlock and the wheellock, and the advent of the flintlock musket of the 17th century, they surpassed the level of earlier Chinese firearms.[63] Illustrations of Ottoman and European riflemen with detailed illustrations of their weapons appeared in Zhao Shizhen's book Shenqipu of 1598,[64] and Ottoman and European firearms were held in great esteem. However, by the 17th century Đại Việt had also been manufacturing muskets of their own, which the Ming considered to be superior to both European and Ottoman firearms, including Japanese imports as well. Vietnamese firearms were copied and disseminated throughout China in quick order.[65]

The 16th-century breech-loading model entered China around 1517 when Fernão Pires de Andrade arrived in China. However, he and the Portuguese embassy were rejected as problems in Ming-Portuguese relations were exacerbated when the Malacca Sultanate, a tributary state of the Ming, was invaded in 1511 by the Portuguese under Afonso de Albuquerque,[66] and in the process a large established Chinese merchant community was slaughtered.[67] The Malacca Sultanate sent the Ming a plea for help but no relief expedition was sent. In 1521 the Portuguese were driven off from China by the Ming navy in a conflict known as the Battle of Tunmen.[68]

Gallery

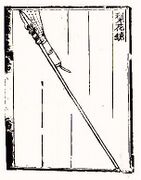

-

An arrow strapped with gunpowder ready to be shot from a bow. The text reads: gong she huo zhe liu jian (bow firing a fiery pomegranate arrow).

-

Rocket arrows from the Huolongjing. The right arrow reads 'fire arrow' (huo jian), the middle is a 'dragon shaped arrow frame' (long xing jian jia), and the left is a 'complete fire arrow' (huo jian quan shi).

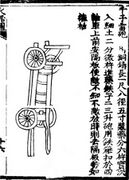

-

A 'divine fire arrow shield' (shen huo jian pai). Depiction of a fire arrow rocket launcher from the Huolongjing.

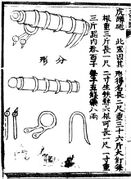

-

A 'watermelon bomb' (xi gua pao) as depicted in the Huolongjing. It contains 'fire rats,' mini rockets with hooks.

-

A 'fire brick' (huo zhuan) as depicted in the Huolongjing. It contains mini-rockets bearing sharp little spikes.

-

Depiction of a' wind-and-dust bomb' (feng chen pao) from the Huolongjing.

-

A 'rumbling thunder bomb' (hong lei pao) as depicted in the Huolongjing. The text describes ingredients including mini-rockets and caltrops with poisons.

-

'Dropping from heaven' (tian zhui pao) bombs as depicted in the Huolongjing.

-

'Bee swarm bombs' (qun feng pao) as depicted in the Huolongjing. Paper casing filled with gunpowder and shrapnel.

-

A 'divine fire meteor which goes against the wind' (zuan feng shen huo liu xing pao) bomb as depicted in the Huolongjing.

-

An illustration of a fragmentation bomb known as the 'divine bone dissolving fire oil bomb' (lan gu huo you shen pao) from the Huolongjing. The black dots represent iron pellets.

-

A 'flying-sand divine bomb releasing ten thousand fires' (wan huo fei sha shen pao) as depicted in the Huolongjing. A weak casing device possibly used in naval combat.

-

'Explosive bombs' (zha pao) from the Huolongjing. The device is operated by steel wheels contained in two boxes. When pressed, the wheel boxes are supposed to ignite a spark reaching the buried gunpowder packages, setting off the explosion.

-

The 'self-tripped trespass land mine' (zi fan pao) from the Huolongjing.

-

An 'explosive camp land mine' (di lei zha ying) from the Huolongjing. The mine is composed of eight explosive charges held erect by two disc shaped frames.

-

A 'pear-flower gun' (li hua qiang). A fire lance as depicted in the Huolongjing.

-

A 'fire gun' (huo qiang). A double barreled fire lance from the Huolongjing. Supposedly they fired in succession, and the second one is lit automatically after the first barrel finishes firing.

-

An 'awe-inspiring fierce-fire yaksha gun' (shen wei lie huo ye cha chong) as depicted in the Huolongjing.

-

A 'lotus bunch' (yi ba lian) as depicted in the Huolongjing. It is a bamboo tube firing darts along with flames.

-

A 'sky-filling spurting-tube' (man tian pen tong) as depicted in the Huolongjing. A bamboo tube filled with a mixture of gunpowder and porcelain fragments.

-

A 'bandit-striking penetrating gun' (ji zei bian chong) as depicted in the Huolongjing. The first known metal barreled fire lance, it throws low nitrate gunpowder flames along with coviative missiles.

-

A 'divine moving phalanx-breaking fierce-fire sword-shield' (shen xing po zhen meng huo dao pai) as depicted in the Huolongjing. A mobile shield fitted with fire lances used to break enemy formations.

-

Essentially a fire lance on a frame, the 'multiple bullets magazine eruptor' (bai zi lian zhu pao) shoots lead shots, which are loaded in a magazine and fed into the barrel when turned around on its axis.

-

A 'poison fog divine smoke eruptor' (du wu shen yan pao) as depicted in the Huolongjing. Small shells emitting poisonous smoke are fired.

-

A canister shot known as the 'flying-hidden-bomb cannon' (fei meng pao shi) from the Huolongjing. The poison canister is loaded into an iron barrel fitted to a wooden tiller.

-

An organ gun known as the 'mother of a hundred bullets gun' (zi mu bai dan chong) from the Huolongjing.

-

A bronze "thousand ball thunder cannon" (qian zi lei pao) from the Huolongjing.

-

An 'awe inspiring long range cannon' (wei yuan pao) from the Huolongjing.

-

The 'crouching tiger cannon' (hu dun pao) as depicted in the Huolongjing.

-

A 'seven star cannon' (qi xing chong) from the Huolongjing. It was a seven barreled organ gun with two auxiliary guns by its side on a two-wheeled carriage.

-

A 'barbarian attacking cannon' (gong rong pao) as depicted in the Huolongjing. Chains are attached to the cannon to adjust recoil. Not to be confused with the "Hongyipao".

-

Reconstruction of the "flying crow with magic fire" (shen huo fei ya).

See also

- Technology of the Song Dynasty

- Jiao Yu

- Liu Bowen

- Gunpowder warfare

- History of gunpowder

- Battle of Tangdao

- Battle of Caishi

- Wujing Zongyao, Chinese military compendium written from around 1040 to 1044.

- Jixiao Xinshu, Chinese military manual written during the 1560s and 1580s.

- Wubei Zhi, Chinese military book was compiled in 1621.

Notes

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 24.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Needham 1986, p. 32.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 23-24.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 33.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 25=27.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 26.

- ↑ Kelly 2004, p. 2.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Khan 2004, p. 2.

- ↑ Ebrey 1999, p. 138.

- ↑ Kelly 2004, p. 4.

- ↑ Yunming 1986, p. 489.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 126.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 32.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 38.

- ↑ Yunming 1986, pp. 489–490.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 345-346.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 173-174.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 192-193.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Cowley 1996, p. 38.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Needham 1986, p. 180.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 187.

- ↑ Needham 1986, pp. 154–155.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Needham 1986, p. 154.

- ↑ Partington 1998, p. 240.

- ↑ Partington 1998, p. 5.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Needham 1986, p. 447.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Needham 1986, pp. 485–486.

- ↑ Needham 1986, pp. 486–489.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 489.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 498.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Temple 1986, p. 240.

- ↑ Needham 1986, pp. 501–503.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 502.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Needham 1986, pp. 508–510.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Temple 1986, pp. 240–241.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 232.

- ↑ (Embree 1997): The term co-viative was introduced ("we need a new word .. and we have decided to call these objects "co-viative"") by Needham (Science in Traditional China: A Comparative Perspective, Harvard U.P., 1981, p.42): "like case shot" but "the pieces of hard, sharp-edged rubbish were actually mixed with .. the [propellant] gunpowder".

- ↑ Needham 1986, pp. 224–225.

- ↑ Embree 1997, p. 185.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Needham 1986, p. 237.

- ↑ Needham 1986, pp. 232–233.

- ↑ Needham 1986, pp. 241–242, 244.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Needham 1986, p. 416.

- ↑ Embree 1997, p. 852.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 293.

- ↑ Needham 1986, pp. 293–294.

- ↑ Norris 2003, p. 10.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Norris 2003, p. 11.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Needham 1986, p. 264.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 267.

- ↑ Needham 1986, pp. 264–265.

- ↑ Needham 1986, pp. 459–463.

- ↑ Needham 1986, pp. 458–459.

- ↑ Partington 1998, p. 239.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 192.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 193.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 199.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 197-199.

- ↑ Needham 1986, pp. 203–205.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 205.

- ↑ Da Jiang Jun Pao (大將軍砲), http://greatmingmilitary.blogspot.com/2015/07/da-jiang-jun-pao.html, retrieved 30 October 2016

- ↑ Khan 2004, p. 4.

- ↑ Khan 2004, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Needham 1986, pp. 447–454.

- ↑ Matchlock firearms of the Ming Dynasty, 10 November 2014, http://greatmingmilitary.blogspot.com/2014/11/matchlock-of-ming-dynasty.html, retrieved 25 February 2017

- ↑ Mote & Twitchett 1998, pp. 338–339.

- ↑ Brook 1998, pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 369.

References

- Andrade, Tonio (2016). The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Brook, Timothy (1998). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Cowley, Robert (1996). The Reader's Companion to Military History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43519-6. (Hardback edition)

- Embree, Ainslie Thomas (1997). Asia in Western and World History: A Guide for Teaching. Armonk: ME Sharpe, Inc..

- Kelly, Jack (2004). Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, and Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World. New York: Basic Books, Perseus Books Group.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2004). Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis (1998). The Cambridge History of China. 7–8. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24333-5. (Hardback edition)

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China. 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology; the Gunpowder Epic. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd..

- Norris, John (2003). Early Gunpowder Artillery: 1300–1600. Marlborough: The Crowood Press, Ltd..

- Partington, James Riddick (1998). A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5954-9.

- Song Yingxing (1966). T'ien-Kung K'ai-Wu: Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Temple, Robert (1986). The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention. With a foreword by Joseph Needham. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-62028-2.

- Yunming, Zhang (1986). Isis: The History of Science Society: Ancient Chinese Sulfur Manufacturing Processes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

External links

|