Isomorphism theorems

In mathematics, specifically abstract algebra, the isomorphism theorems (also known as Noether's isomorphism theorems) are theorems that describe the relationship between quotients, homomorphisms, and subobjects. Versions of the theorems exist for groups, rings, vector spaces, modules, Lie algebras, and various other algebraic structures. In universal algebra, the isomorphism theorems can be generalized to the context of algebras and congruences.

History

The isomorphism theorems were formulated in some generality for homomorphisms of modules by Emmy Noether in her paper Abstrakter Aufbau der Idealtheorie in algebraischen Zahl- und Funktionenkörpern, which was published in 1927 in Mathematische Annalen. Less general versions of these theorems can be found in work of Richard Dedekind and previous papers by Noether.

Three years later, B.L. van der Waerden published his influential Moderne Algebra, the first abstract algebra textbook that took the groups-rings-fields approach to the subject. Van der Waerden credited lectures by Noether on group theory and Emil Artin on algebra, as well as a seminar conducted by Artin, Wilhelm Blaschke, Otto Schreier, and van der Waerden himself on ideals as the main references. The three isomorphism theorems, called homomorphism theorem, and two laws of isomorphism when applied to groups, appear explicitly.

Groups

We first present the isomorphism theorems of the groups.

Theorem A (groups)

Let G and H be groups, and let f : G → H be a homomorphism. Then:

- The kernel of f is a normal subgroup of G,

- The image of f is a subgroup of H, and

- The image of f is isomorphic to the quotient group G / ker(f).

In particular, if f is surjective then H is isomorphic to G / ker(f).

This theorem is usually called the first isomorphism theorem.

Theorem B (groups)

Let be a group. Let be a subgroup of , and let be a normal subgroup of . Then the following hold:

- The product is a subgroup of ,

- The subgroup is a normal subgroup of ,

- The intersection is a normal subgroup of , and

- The quotient groups and are isomorphic.

Technically, it is not necessary for to be a normal subgroup, as long as is a subgroup of the normalizer of in . In this case, is not a normal subgroup of , but is still a normal subgroup of the product .

This theorem is sometimes called the second isomorphism theorem,[1] diamond theorem[2] or the parallelogram theorem.[3]

An application of the second isomorphism theorem identifies projective linear groups: for example, the group on the complex projective line starts with setting , the group of invertible 2 × 2 complex matrices, , the subgroup of determinant 1 matrices, and the normal subgroup of scalar matrices , we have , where is the identity matrix, and . Then the second isomorphism theorem states that:

Theorem C (groups)

Let be a group, and a normal subgroup of . Then

- If is a subgroup of such that , then has a subgroup isomorphic to .

- Every subgroup of is of the form for some subgroup of such that .

- If is a normal subgroup of such that , then has a normal subgroup isomorphic to .

- Every normal subgroup of is of the form for some normal subgroup of such that .

- If is a normal subgroup of such that , then the quotient group is isomorphic to .

The last statement is sometimes referred to as the third isomorphism theorem. The first four statements are often subsumed under Theorem D below, and referred to as the lattice theorem, correspondence theorem, or fourth isomorphism theorem.

Theorem D (groups)

Let be a group, and a normal subgroup of . The canonical projection homomorphism defines a bijective correspondence between the set of subgroups of containing and the set of (all) subgroups of . Under this correspondence normal subgroups correspond to normal subgroups.

This theorem is sometimes called the correspondence theorem, the lattice theorem, and the fourth isomorphism theorem.

The Zassenhaus lemma (also known as the butterfly lemma) is sometimes called the fourth isomorphism theorem.[4]

Discussion

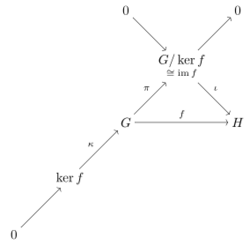

The first isomorphism theorem can be expressed in category theoretical language by saying that the category of groups is (normal epi, mono)-factorizable; in other words, the normal epimorphisms and the monomorphisms form a factorization system for the category. This is captured in the commutative diagram in the margin, which shows the objects and morphisms whose existence can be deduced from the morphism . The diagram shows that every morphism in the category of groups has a kernel in the category theoretical sense; the arbitrary morphism f factors into , where ι is a monomorphism and π is an epimorphism (in a conormal category, all epimorphisms are normal). This is represented in the diagram by an object and a monomorphism (kernels are always monomorphisms), which complete the short exact sequence running from the lower left to the upper right of the diagram. The use of the exact sequence convention saves us from having to draw the zero morphisms from to and .

If the sequence is right split (i.e., there is a morphism σ that maps to a π-preimage of itself), then G is the semidirect product of the normal subgroup and the subgroup . If it is left split (i.e., there exists some such that ), then it must also be right split, and is a direct product decomposition of G. In general, the existence of a right split does not imply the existence of a left split; but in an abelian category (such as that of abelian groups), left splits and right splits are equivalent by the splitting lemma, and a right split is sufficient to produce a direct sum decomposition . In an abelian category, all monomorphisms are also normal, and the diagram may be extended by a second short exact sequence .

In the second isomorphism theorem, the product SN is the join of S and N in the lattice of subgroups of G, while the intersection S ∩ N is the meet.

The third isomorphism theorem is generalized by the nine lemma to abelian categories and more general maps between objects.

Note on numbers and names

Below we present four theorems, labelled A, B, C and D. They are often numbered as "First isomorphism theorem", "Second..." and so on; however, there is no universal agreement on the numbering. Here we give some examples of the group isomorphism theorems in the literature. Notice that these theorems have analogs for rings and modules.

| Comment | Author | Theorem A | Theorem B | Theorem C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No "third" theorem | Jacobson[5] | Fundamental theorem of homomorphisms | (Second isomorphism theorem) | "often called the first isomorphism theorem" |

| van der Waerden,[6] Durbin[8] | Fundamental theorem of homomorphisms | First isomorphism theorem | Second isomorphism theorem | |

| Knapp[9] | (No name) | Second isomorphism theorem | First isomorphism theorem | |

| Grillet[10] | Homomorphism theorem | Second isomorphism theorem | First isomorphism theorem | |

| Three numbered theorems | (Other convention per Grillet) | First isomorphism theorem | Third isomorphism theorem | Second isomorphism theorem |

| Rotman[11] | First isomorphism theorem | Second isomorphism theorem | Third isomorphism theorem | |

| Fraleigh[12] | Fundamental homomorphism theorem or first isomorphism theorem | Second isomorphism theorem | Third isomorphism theorem | |

| Dummit & Foote[13] | First isomorphism theorem | Second or Diamond isomorphism theorem | Third isomorphism theorem | |

| No numbering | Milne[1] | Homomorphism theorem | Isomorphism theorem | Correspondence theorem |

| Scott[14] | Homomorphism theorem | Isomorphism theorem | Freshman theorem |

It is less common to include the Theorem D, usually known as the lattice theorem or the correspondence theorem, as one of isomorphism theorems, but when included, it is the last one.

Rings

The statements of the theorems for rings are similar, with the notion of a normal subgroup replaced by the notion of an ideal.

Theorem A (rings)

Let and be rings, and let be a ring homomorphism. Then:

- The kernel of is an ideal of ,

- The image of is a subring of , and

- The image of is isomorphic to the quotient ring .

In particular, if is surjective then is isomorphic to .[15]

Theorem B (rings)

Let R be a ring. Let S be a subring of R, and let I be an ideal of R. Then:

- The sum S + I = {s + i | s ∈ S, i ∈ I } is a subring of R,

- The intersection S ∩ I is an ideal of S, and

- The quotient rings (S + I) / I and S / (S ∩ I) are isomorphic.

Theorem C (rings)

Let R be a ring, and I an ideal of R. Then

- If is a subring of such that , then is a subring of .

- Every subring of is of the form for some subring of such that .

- If is an ideal of such that , then is an ideal of .

- Every ideal of is of the form for some ideal of such that .

- If is an ideal of such that , then the quotient ring is isomorphic to .

Theorem D (rings)

Let be an ideal of . The correspondence is an inclusion-preserving bijection between the set of subrings of that contain and the set of subrings of . Furthermore, (a subring containing ) is an ideal of if and only if is an ideal of .[16]

Modules

The statements of the isomorphism theorems for modules are particularly simple, since it is possible to form a quotient module from any submodule. The isomorphism theorems for vector spaces (modules over a field) and abelian groups (modules over ) are special cases of these. For finite-dimensional vector spaces, all of these theorems follow from the rank–nullity theorem.

In the following, "module" will mean "R-module" for some fixed ring R.

Theorem A (modules)

Let M and N be modules, and let φ : M → N be a module homomorphism. Then:

- The kernel of φ is a submodule of M,

- The image of φ is a submodule of N, and

- The image of φ is isomorphic to the quotient module M / ker(φ).

In particular, if φ is surjective then N is isomorphic to M / ker(φ).

Theorem B (modules)

Let M be a module, and let S and T be submodules of M. Then:

- The sum S + T = {s + t | s ∈ S, t ∈ T} is a submodule of M,

- The intersection S ∩ T is a submodule of M, and

- The quotient modules (S + T) / T and S / (S ∩ T) are isomorphic.

Theorem C (modules)

Let M be a module, T a submodule of M.

- If is a submodule of such that , then is a submodule of .

- Every submodule of is of the form for some submodule of such that .

- If is a submodule of such that , then the quotient module is isomorphic to .

Theorem D (modules)

Let be a module, a submodule of . There is a bijection between the submodules of that contain and the submodules of . The correspondence is given by for all . This correspondence commutes with the processes of taking sums and intersections (i.e., is a lattice isomorphism between the lattice of submodules of and the lattice of submodules of that contain ).[17]

Universal algebra

To generalise this to universal algebra, normal subgroups need to be replaced by congruence relations.

A congruence on an algebra is an equivalence relation that forms a subalgebra of considered as an algebra with componentwise operations. One can make the set of equivalence classes into an algebra of the same type by defining the operations via representatives; this will be well-defined since is a subalgebra of . The resulting structure is the quotient algebra.

Theorem A (universal algebra)

Let be an algebra homomorphism. Then the image of is a subalgebra of , the relation given by (i.e. the kernel of ) is a congruence on , and the algebras and are isomorphic. (Note that in the case of a group, iff , so one recovers the notion of kernel used in group theory in this case.)

Theorem B (universal algebra)

Given an algebra , a subalgebra of , and a congruence on , let be the trace of in and the collection of equivalence classes that intersect . Then

- is a congruence on ,

- is a subalgebra of , and

- the algebra is isomorphic to the algebra .

Theorem C (universal algebra)

Let be an algebra and two congruence relations on such that . Then is a congruence on , and is isomorphic to

Theorem D (universal algebra)

Let be an algebra and denote the set of all congruences on . The set is a complete lattice ordered by inclusion.[18] If is a congruence and we denote by the set of all congruences that contain (i.e. is a principal filter in , moreover it is a sublattice), then the map is a lattice isomorphism.[19][20]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Milne (2013), Chap. 1, sec. Theorems concerning homomorphisms

- ↑ I. Martin Isaacs (1994). Algebra: A Graduate Course. American Mathematical Soc.. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8218-4799-2. https://archive.org/details/algebragraduatec00isaa.

- ↑ Paul Moritz Cohn (2000). Classic Algebra. Wiley. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-471-87731-8. https://archive.org/details/classicalgebra00cohn_300.

- ↑ Wilson, Robert A. (2009). The Finite Simple Groups. Graduate Texts in Mathematics 251. 251. Springer-Verlag London. p. 7. doi:10.1007/978-1-84800-988-2. ISBN 978-1-4471-2527-3.

- ↑ Jacobson (2009), sec 1.10

- ↑ van der Waerden, Algebra (1994).

- ↑ Durbin (2009), sec. 54

- ↑ [the names are] essentially the same as [van der Waerden 1994][7]

- ↑ Knapp (2016), sec IV 2

- ↑ Grillet (2007), sec. I 5

- ↑ Rotman (2003), sec. 2.6

- ↑ Fraleigh (2003), Chap. 14, 34

- ↑ Dummit, David Steven (2004). Abstract algebra. Richard M. Foote (Third ed.). Hoboken, NJ. pp. 97–98. ISBN 0-471-43334-9. OCLC 52559229. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/52559229.

- ↑ Scott (1964), secs 2.2 and 2.3

- ↑ Moy, Samuel (2022). "An Introduction to the Theory of Field Extensions". https://math.uchicago.edu/~may/VIGRE/VIGRE2009/REUPapers/Moy.pdf.

- ↑ Dummit, David S.; Foote, Richard M. (2004). Abstract algebra. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-471-43334-7. https://archive.org/details/abstractalgebra00dumm_304.

- ↑ Dummit and Foote (2004), p. 349

- ↑ Burris and Sankappanavar (2012), p. 37

- ↑ Burris and Sankappanavar (2012), p. 49

- ↑ Sun, William. "Is there a general form of the correspondence theorem?". https://math.stackexchange.com/q/2850331.

References

- Noether, Emmy, Abstrakter Aufbau der Idealtheorie in algebraischen Zahl- und Funktionenkörpern, Mathematische Annalen 96 (1927) pp. 26–61

- McLarty, Colin, "Emmy Noether's 'Set Theoretic' Topology: From Dedekind to the rise of functors". The Architecture of Modern Mathematics: Essays in history and philosophy (edited by Jeremy Gray and José Ferreirós), Oxford University Press (2006) pp. 211–35.

- Jacobson, Nathan (2009), Basic algebra, 1 (2nd ed.), Dover, ISBN 9780486471891

- Cohn, Paul M., Universal algebra, Chapter II.3 p. 57

- Milne, James S. (2013), Group Theory, 3.13, http://www.jmilne.org/math/

- van der Waerden, B. I. (1994), Algebra, 1 (9 ed.), Springer-Verlag

- Dummit, David S.; Foote, Richard M. (2004). Abstract algebra. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-43334-7.

- Burris, Stanley; Sankappanavar, H. P. (2012). A Course in Universal Algebra. ISBN 978-0-9880552-0-9. https://www.math.uwaterloo.ca/~snburris/htdocs/UALG/univ-algebra2012.pdf.

- Scott, W. R. (1964), Group Theory, Prentice Hall

- Durbin, John R. (2009). Modern Algebra: An Introduction (6 ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-38443-5.

- Knapp, Anthony W. (2016), Basic Algebra (Digital second ed.)

- Grillet, Pierre Antoine (2007), Abstract Algebra (2 ed.), Springer

- Rotman, Joseph J. (2003), Advanced Modern Algebra (2 ed.), Prentice Hall, ISBN 0130878685

- Hungerford, Thomas W. (1980), Algebra (Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 73), Springer, ISBN 0387905189

|