Lemniscate constant

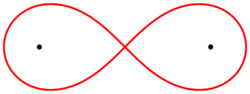

In mathematics, the lemniscate constant ϖ is a transcendental mathematical constant that is the ratio of the perimeter of Bernoulli's lemniscate to its diameter, analogous to the definition of π for the circle.[1] Equivalently, the perimeter of the lemniscate is . The lemniscate constant is closely related to the lemniscate elliptic functions and approximately equal to 2.62205755.[2] It also appears in evaluation of the gamma and beta function at certain rational values. The symbol ϖ is a cursive variant of π known as variant pi represented in Unicode by the character U+03D6 ϖ .

Sometimes the quantities 2ϖ or ϖ/2 are referred to as the lemniscate constant.[3][4]

History

Gauss's constant, denoted by G, is equal to ϖ /π ≈ 0.8346268[5] and named after Carl Friedrich Gauss, who calculated it via the arithmetic–geometric mean as .[6] By 1799, Gauss had two proofs of the theorem that where is the lemniscate constant.[7]

John Todd named two more lemniscate constants, the first lemniscate constant A = ϖ/2 ≈ 1.3110287771 and the second lemniscate constant B = π/(2ϖ) ≈ 0.5990701173.[8][9][10]

The lemniscate constant and Todd's first lemniscate constant were proven transcendental by Carl Ludwig Siegel in 1932 and later by Theodor Schneider in 1937 and Todd's second lemniscate constant and Gauss's constant were proven transcendental by Theodor Schneider in 1941.[8][11][12] In 1975, Gregory Chudnovsky proved that the set is algebraically independent over , which implies that and are algebraically independent as well.[13][14] But the set (where the prime denotes the derivative with respect to the second variable) is not algebraically independent over .[15] In 1996, Yuri Nesterenko proved that the set is algebraically independent over .[16]

As of 2025 over 2 trillion digits of this constant have been calculated using y-cruncher.[17]

Forms

Usually, is defined by the first equality below, but it has many equivalent forms:[18]

where K is the complete elliptic integral of the first kind with modulus k, Β is the beta function, Γ is the gamma function and ζ is the Riemann zeta function.

The lemniscate constant can also be computed by the arithmetic–geometric mean ,

Gauss's constant is typically defined as the reciprocal of the arithmetic–geometric mean of 1 and the square root of 2, after his calculation of published in 1800:[19]John Todd's lemniscate constants may be given in terms of the beta function B:

As a special value of L-functions

which is analogous to

where is the Dirichlet beta function and is the Riemann zeta function.[20]

Analogously to the Leibniz formula for π, we have[21][22][23][24][25] where is the L-function of the elliptic curve over ; this means that is the multiplicative function given by where is the number of solutions of the congruence in variables that are non-negative integers ( is the set of all primes). Equivalently, is given by where such that and is the eta function.[26][27][28] The above result can be equivalently written as (the number is the conductor of ) and also tells us that the BSD conjecture is true for the above .[29] The first few values of are given by the following table; if such that doesn't appear in the table, then :

As a special value of other functions

Let be the minimal weight level new form. Then[30] The -coefficient of is the Ramanujan tau function.

Series

Viète's formula for π can be written:

An analogous formula for ϖ is:[31]

The Wallis product for π is:

An analogous formula for ϖ is:[32]

A related result for Gauss's constant () is:[33]

An infinite series discovered by Gauss is:[34]

The Machin formula for π is and several similar formulas for π can be developed using trigonometric angle sum identities, e.g. Euler's formula . Analogous formulas can be developed for ϖ, including the following found by Gauss: , where is the lemniscate arcsine.[35]

The lemniscate constant can be rapidly computed by the series[36][37]

where (these are the generalized pentagonal numbers). Also[38]

In a spirit similar to that of the Basel problem,

where are the Gaussian integers and is the Eisenstein series of weight (see Lemniscate elliptic functions § Hurwitz numbers for a more general result).[39]

A related result is

where is the sum of positive divisors function.[40]

In 1842, Malmsten found

where is Euler's constant and is the Dirichlet-Beta function.

The lemniscate constant is given by the rapidly converging series

The constant is also given by the infinite product

Also[41]

Continued fractions

A (generalized) continued fraction for π is An analogous formula for ϖ is[9]

Define Brouncker's continued fraction by[42] Let except for the first equality where . Then[43][44] For example,

In fact, the values of and , coupled with the functional equation determine the values of for all .

Simple continued fractions

Simple continued fractions for the lemniscate constant and related constants include[45][46]

Integrals

The lemniscate constant ϖ is related to the area under the curve . Defining , twice the area in the positive quadrant under the curve is In the quartic case,

In 1842, Malmsten discovered that[47]

Furthermore,

and[48]

a form of Gaussian integral.

The lemniscate constant appears in the evaluation of the integrals

John Todd's lemniscate constants are defined by integrals:[8]

Circumference of an ellipse

The lemniscate constant satisfies the equation[49]

Euler discovered in 1738 that for the rectangular elastica (first and second lemniscate constants)[50][49]

Now considering the circumference of the ellipse with axes and , satisfying , Stirling noted that[51]

Hence the full circumference is

This is also the arc length of the sine curve on half a period:[52]

Other limits

Analogously to where are Bernoulli numbers, we have where are Hurwitz numbers.

Notes

- ↑ See:

- Gauss, C. F. (1866) (in Latin, German). Werke (Band III). Herausgegeben der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. https://gdz.sub.uni-goettingen.de/id/PPN235999628. p. 404

- Cox 1984, p. 281

- Eymard, Pierre; Lafon, Jean-Pierre (2004). The Number Pi. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 0-8218-3246-8. p. 199

- Bottazzini, Umberto; Gray, Jeremy (2013). Hidden Harmony – Geometric Fantasies: The Rise of Complex Function Theory. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-5725-1. ISBN 978-1-4614-5724-4. p. 57

- Arakawa, Tsuneo; Ibukiyama, Tomoyoshi; Kaneko, Masanobu (2014). Bernoulli Numbers and Zeta Functions. Springer. ISBN 978-4-431-54918-5. p. 203

- ↑ See:

- Finch 2003, p. 420

- Kobayashi, Hiroyuki; Takeuchi, Shingo (2019), "Applications of generalized trigonometric functions with two parameters", Communications on Pure & Applied Analysis 18 (3): 1509–1521, doi:10.3934/cpaa.2019072

- Asai, Tetsuya (2007), Elliptic Gauss Sums and Hecke L-values at s=1

- "A062539 - Oeis". http://oeis.org/A062539.

- ↑ "A064853 - Oeis". http://oeis.org/A064853.

- ↑ "Lemniscate Constant". http://www.numberworld.org/digits/Lemniscate/.

- ↑ "A014549 - Oeis". http://oeis.org/A014549.

- ↑ Finch 2003, p. 420.

- ↑ Neither of these proofs was rigorous from the modern point of view. See Cox 1984, p. 281

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Todd, John (January 1975). "The lemniscate constants". Communications of the ACM 18 (1): 14–19. doi:10.1145/360569.360580.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "A085565 - Oeis". http://oeis.org/A085565. and "A076390 - Oeis". http://oeis.org/A076390.

- ↑ Carlson, B. C. (2010), "Elliptic Integrals", in Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F. et al., NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-19225-5, http://dlmf.nist.gov/19.20.E2

- ↑ In particular, Siegel proved that if and with are algebraic, then or is transcendental. Here, and are Eisenstein series. The fact that is transcendental follows from and Apostol, T. M. (1990). Modular Functions and Dirichlet Series in Number Theory (Second ed.). Springer. p. 12. ISBN 0-387-97127-0. Siegel, C. L. (1932). "Über die Perioden elliptischer Funktionen." (in German). Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 167: 62–69. doi:10.1515/crll.1932.167.62. https://eudml.org/doc/149791.

- ↑ In particular, Schneider proved that the beta function is transcendental for all such that . The fact that is transcendental follows from and similarly for B and G from Schneider, Theodor (1941). "Zur Theorie der Abelschen Funktionen und Integrale". Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 183 (19): 110–128. doi:10.1515/crll.1941.183.110. https://www.deepdyve.com/lp/de-gruyter/zur-theorie-der-abelschen-funktionen-und-integrale-mn0U50bvkB.

- ↑ G. V. Choodnovsky: Algebraic independence of constants connected with the functions of analysis, Notices of the AMS 22, 1975, p. A-486

- ↑ G. V. Chudnovsky: Contributions to The Theory of Transcendental Numbers, American Mathematical Society, 1984, p. 6

- ↑ In fact, Borwein, Jonathan M.; Borwein, Peter B. (1987). Pi and the AGM: A Study in Analytic Number Theory and Computational Complexity (First ed.). Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 0-471-83138-7. p. 45

- ↑ Nesterenko, Y. V.; Philippon, P. (2001). Introduction to Algebraic Independence Theory. Springer. p. 27. ISBN 3-540-41496-7.

- ↑ Yee, Alexander J. (May 18, 2025). "Records set by y-cruncher". http://numberworld.org/y-cruncher/records.html.

- ↑ See:

- Cox 1984, p. 281

- Finch 2003, pp. 420–422

- Schappacher, Norbert (1997). "Some milestones of lemniscatomy". in Sertöz, S.. Algebraic Geometry (Proceedings of Bilkent Summer School, August 7–19, 1995, Ankara, Turkey). Marcel Dekker. pp. 257–290. http://irma.math.unistra.fr/~schappa/NSch/Publications_files/1997_LemniscProvis.pdf.

- ↑ Cox 1984, p. 277.

- ↑ "A113847 - Oeis". http://oeis.org/A113847.

- ↑ Cremona, J. E. (1997). Algorithms for Modular Elliptic Curves (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521598206. https://books.google.com/books?id=MtM8AAAAIAAJ. p. 31, formula (2.8.10)

- ↑ In fact, the series converges for .

- ↑ Murty, Vijaya Kumar (1995). Seminar on Fermat's Last Theorem. American Mathematical Society. p. 16. ISBN 9780821803134.

- ↑ Cohen, Henri (1993). A Course in Computational Algebraic Number Theory. Springer-Verlag. pp. 382–406. ISBN 978-3-642-08142-2.

- ↑ "Elliptic curve with LMFDB label 32.a3 (Cremona label 32a2)". https://www.lmfdb.org/EllipticCurve/Q/32/a/3.

- ↑ The function is the unique weight level new form and it satisfies the functional equation

- ↑ The function is closely related to the function which is the multiplicative function defined by

- ↑ The function also appears in

- ↑ Rubin, Karl (1987). "Tate-Shafarevich groups and L-functions of elliptic curves with complex multiplication". Inventiones Mathematicae 89 (3): 528. doi:10.1007/BF01388984. Bibcode: 1987InMat..89..527R. https://eudml.org/doc/143493.

- ↑ "Newform orbit 1.12.a.a". https://www.lmfdb.org/ModularForm/GL2/Q/holomorphic/1/12/a/a/.

- ↑ Levin (2006)

- ↑ Hyde (2014) proves the validity of a more general Wallis-like formula for clover curves; here the special case of the lemniscate is slightly transformed, for clarity.

- ↑ Hyde, Trevor (2014). "A Wallis product on clovers". The American Mathematical Monthly 121 (3): 237–243. doi:10.4169/amer.math.monthly.121.03.237. https://math.uchicago.edu/~tghyde/Hyde%20--%20A%20Wallis%20product%20on%20clovers.pdf. Retrieved 2021-10-29.

- ↑ Bottazzini, Umberto; Gray, Jeremy (2013). Hidden Harmony – Geometric Fantasies: The Rise of Complex Function Theory. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-5725-1. ISBN 978-1-4614-5724-4. p. 60

- ↑ Todd (1975)

- ↑ Cox 1984, p. 307, eq. 2.21 for the first equality. The second equality can be proved by using the pentagonal number theorem.

- ↑ Berndt, Bruce C. (1998). Ramanujan's Notebooks Part V. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4612-7221-2. p. 326

- ↑ This formula can be proved by hypergeometric inversion: Let

- ↑ Eymard, Pierre; Lafon, Jean-Pierre (2004). The Number Pi. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 0-8218-3246-8. p. 232

- ↑ Garrett, Paul. "Level-one elliptic modular forms". http://www-users.math.umn.edu/~garrett/m/mfms/notes_2015-16/10_level_one.pdf. p. 11—13

- ↑ The formula follows from the hypergeometric transformation

- ↑ Khrushchev, Sergey (2008). Orthogonal Polynomials and Continued Fractions (First ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85419-1. p. 140 (eq. 3.34), p. 153. There's an error on p. 153: should be .

- ↑ Khrushchev, Sergey (2008). Orthogonal Polynomials and Continued Fractions (First ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85419-1. p. 146, 155

- ↑ Perron, Oskar (1957) (in German). Die Lehre von den Kettenbrüchen: Band II (Third ed.). B. G. Teubner. p. 36, eq. 24

- ↑ "A062540 - OEIS". http://oeis.org/A062540.

- ↑ "A053002 - OEIS". http://oeis.org/A053002.

- ↑ Blagouchine, Iaroslav V. (2014). "Rediscovery of Malmsten's integrals, their evaluation by contour integration methods and some related results". The Ramanujan Journal 35 (1): 21–110. doi:10.1007/s11139-013-9528-5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257381156.

- ↑ "A068467 - Oeis". https://oeis.org/A068467.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Cox 1984, p. 313.

- ↑ Levien (2008)

- ↑ Cox 1984, p. 312.

- ↑ Adlaj, Semjon (2012). "An Eloquent Formula for the Perimeter of an Ellipse". p. 1097. https://www.ams.org/notices/201208/rtx120801094p.pdf. "One might also observe that the length of the “sine” curve over half a period, that is, the length of the graph of the function from the point where to the point where , is ." In this paper and .

References

- Cox, David A. (January 1984). "The Arithmetic-Geometric Mean of Gauss". L'Enseignement Mathématique 30 (2): 275–330. doi:10.5169/seals-53831. https://webspace.science.uu.nl/~wepst101/elliptic/cox_agm.pdf. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- Finch, Steven R. (18 August 2003) (in en). Mathematical Constants. Cambridge University Press. pp. 420–422. ISBN 978-0-521-81805-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=Pl5I2ZSI6uAC.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Lemniscate Constant". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/LemniscateConstant.html.

- Sequences A014549, A053002, and A062539 in OEIS

|