Physics:Isotropic radiator

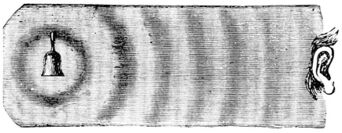

An isotropic radiator is a theoretical point source of waves that radiates the same intensity of radiation in all directions.[1][2][3][4] It may be based on sound waves or electromagnetic waves, in which case it is also known as an isotropic antenna. It has no preferred direction of radiation, i.e., it radiates uniformly in all directions over a sphere centred on the source.

Isotropic radiators are used as reference radiators with which other sources are compared, for example in determining the gain of antennas. A coherent isotropic radiator of electromagnetic waves is theoretically impossible, but incoherent radiators can be built. An isotropic sound radiator is possible because sound is a longitudinal wave.

The term isotropic radiation means a radiation field which has the same intensity in all directions at each receiving point; thus an isotropic radiator does not produce isotropic radiation.[5][6]

Physics

In physics, an isotropic radiator is a point radiation or sound source.[7]: 6 At a distance, the Sun and other stars are isotropic radiators of electromagnetic radiation.

Radiation pattern

The radiation field of an isotropic radiator in empty space can be found from conservation of energy. The waves travel in straight lines away from the source point, in the radial direction . Since it has no preferred direction of radiation, the power density [8] of the waves at any point does not depend on the angular direction , but only on the distance from the source. Assuming it is located in empty space where there is nothing to absorb the waves, the power striking a spherical surface enclosing the radiator, with the radiator at center, regardless of the radius , must be the total power in watts emitted by the source. Since the power density in watts per square meter striking each point of the sphere is the same, it must equal the radiated power divided by the surface area of the sphere[3][9][7]: eq. 1.2.5

Thus the power density radiated by an isotropic radiator decreases with the inverse square of the distance from the source.

The term isotropic radiation is not used for the radiation from an isotropic radiator because it has a different meaning in physics. In thermodynamics it refers to the electromagnetic radiation pattern which would be found in a region at thermodynamic equilibrium, as in a black thermal cavity at a constant temperature.[5] In a cavity at equilibrium the power density of radiation is the same in every direction and every point in the cavity, meaning that the amount of power passing through a unit surface is constant at any location, and with the surface oriented in any direction.[6][5] This radiation field is different from that of an isotropic radiator, in which the direction of power flow is everywhere away from the source point, and decreases with the inverse square of distance from it.

Antenna theory

In antenna theory, an isotropic antenna is a hypothetical antenna radiating the same intensity of radio waves in all directions.[1] It thus is said to have a directivity of 0 dBi (dB relative to isotropic) in all directions. Since it is entirely non-directional, it serves as a hypothetical worst-case against which directional antennas may be compared.

In reality, a coherent isotropic radiator of electromagnetic waves of linear polarization can be shown to be impossible.[10][lower-alpha 1] Its radiation field could not be consistent with the Helmholtz wave equation (derived from Maxwell's equations) in all directions simultaneously. Consider a large sphere surrounding the hypothetical point source, in the far field of the radiation pattern so that at that radius the wave over a reasonable area is essentially planar. In the far field the electric (and magnetic) field of a plane wave in free space is always perpendicular to the direction of propagation of the wave. So the electric field would have to be tangent to the surface of the sphere everywhere, and continuous along that surface. However the hairy ball theorem shows that a continuous vector field tangent to the surface of a sphere must fall to zero at one or more points on the sphere, which is inconsistent with the assumption of an isotropic radiator with linear polarization.

Incoherent isotropic antennas are possible and do not violate Maxwell's equations. Even though an exactly isotropic antenna cannot exist in practice, it is used as a base of comparison to calculate the directivity of actual antennas. Antenna gain which is equal to the antenna's directivity multiplied by the antenna efficiency, is defined as the ratio of the intensity (power per unit area) of the radio power received at a given distance from the antenna (in the direction of maximum radiation) to the intensity received from a perfect lossless isotropic antenna at the same distance. This is called isotropic gain Gain is often expressed in logarithmic units called decibels (dB). When gain is calculated with respect to an isotropic antenna, these are called decibels isotropic (dBi) The gain of any perfectly efficient antenna averaged over all directions is unity, or 0 dBi.

Isotropic receiver

In EMF measurement applications, an isotropic receiver (also called isotropic antenna) is a calibrated radio receiver with an antenna which approximates an isotropic reception pattern; that is, it has close to equal sensitivity to radio waves from any direction. It is used as a field measurement instrument to measure electromagnetic sources and calibrate antennas. The isotropic receiving antenna is usually approximated by three orthogonal antennas or sensing devices with a radiation pattern of the omnidirectional type such as short dipoles or small loop antennas.

The parameter used to define accuracy in the measurements is called isotropic deviation.

Optics

In optics, an isotropic radiator is a point source of light. The Sun approximates an (incoherent) isotropic radiator of light. Certain munitions such as flares and chaff have isotropic radiator properties. Whether a radiator is isotropic is independent of whether it obeys Lambert's law. As radiators, a spherical black body is both, a flat black body is Lambertian but not isotropic, a flat chrome sheet is neither, and by symmetry the Sun is isotropic, but not Lambertian on account of limb darkening.

Sound

An isotropic sound radiator is a theoretical loudspeaker radiating equal sound volume in all directions. Since sound waves are longitudinal waves, a coherent isotropic sound radiator is feasible; an example is a pulsing spherical membrane or diaphragm, whose surface expands and contracts radially with time, pushing on the air.[11]

Derivation of aperture of an isotropic antenna

The aperture of an isotropic antenna can be derived by a thermodynamic argument, which follows.[12][13][14]

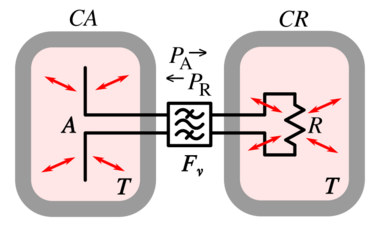

Suppose an ideal (lossless) isotropic antenna A located within a thermal cavity CA is connected via a lossless transmission line through a band-pass filter Fν to a matched resistor R in another thermal cavity CR (the characteristic impedance of the antenna, line and filter are all matched). Both cavities are at the same temperature The filter Fν only allows through a narrow band of frequencies from to Both cavities are filled with blackbody radiation in equilibrium with the antenna and resistor. Some of this radiation is received by the antenna.

The amount of this power within the band of frequencies passes through the transmission line and filter Fν and is dissipated as heat in the resistor. The rest is reflected by the filter back to the antenna and is reradiated into the cavity. The resistor also produces Johnson–Nyquist noise current due to the random motion of its molecules at the temperature The amount of this power within the frequency band passes through the filter and is radiated by the antenna. Since the entire system is at the same temperature it is in thermodynamic equilibrium; there can be no net transfer of power between the cavities, otherwise one cavity would heat up and the other would cool down in violation of the second law of thermodynamics. Therefore, the power flows in both directions must be equal

The radio noise in the cavity is unpolarized, containing an equal mixture of polarization states. However any antenna with a single output is polarized, and can only receive one of two orthogonal polarization states. For example, a linearly polarized antenna cannot receive components of radio waves with electric field perpendicular to the antenna's linear elements; similarly a right circularly polarized antenna cannot receive left circularly polarized waves. Therefore, the antenna only receives the component of power density S in the cavity matched to its polarization, which is half of the total power density Suppose is the spectral radiance per hertz in the cavity; the power of black-body radiation per unit area (m2) per unit solid angle (steradian) per unit frequency (hertz) at frequency and temperature in the cavity. If is the antenna's aperture, the amount of power in the frequency range the antenna receives from an increment of solid angle in the direction is To find the total power in the frequency range the antenna receives, this is integrated over all directions (a solid angle of ) Since the antenna is isotropic, it has the same aperture in any direction. So the aperture can be moved outside the integral. Similarly the radiance in the cavity is the same in any direction Radio waves are low enough in frequency so the Rayleigh–Jeans formula gives a very close approximation of the blackbody spectral radiance[lower-alpha 2] Therefore

The Johnson–Nyquist noise power produced by a resistor at temperature over a frequency range is Since the cavities are in thermodynamic equilibrium so

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Acoustic isotropic radiators, however, are possible because sound waves in a gas or liquid are longitudinal waves and not transverse waves (as electromagnetic waves are).

- ↑ The Rayleigh-Jeans formula is a good approximation as long as the energy in a radio photon is small compared with the thermal energy per degree of freedom: This is true throughout the radio spectrum at all ordinary temperatures.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Graf, Rudolph F. (1999). Modern Dictionary of Electronics. Newnes. pp. 398. ISBN 9780750698665. https://books.google.com/books?id=o2I1JWPpdusC&q=%isotropic+antenna%&pg=PA398.

- ↑ "Isotropic radiator". Electronic engineering glossary. In Compliance magazine website. 2009. https://incompliancemag.com/terms/isotropic-radiator/. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Richards, John A. (2008). Radio Wave Propagation: An introduction for the nonspecialist. Springer-Verlag. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9783540771241. https://books.google.com/books?id=WaLIUSljsEAC&dq=%22isotropic+radiator%22+source+power+physics&pg=PA2.

- ↑ Weik, Martin H. (1989). Communications Standard Dictionary, 2nd Ed.. Van Nostrand Reinhold. pp. 555. ISBN 9781461566748. https://books.google.com/books?id=lv3xBwAAQBAJ&dq=%22isotropic+radiator%22&pg=PA555.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Howell, John R.; Menguc, M. Pinar; Siegal, Robert (2016). Thermal Radiation Heat Transfer, 6th Ed.. CRC Press. pp. 15. ISBN 9781498757744. https://books.google.com/books?id=aeSYCgAAQBAJ&q=%22isotropic+radiation%22.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Demtroder, Wolfgang (2010). Atoms, Molecules, and Photons. Springer. pp. 83. ISBN 9783642102974. https://books.google.com/books?id=vbc5mA7OEuYC&q=isotropic.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Karp, Sherman; Gagliardi, Robert M.; Moran, Steven E. (1988). Optical Channels. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781489908063. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Optical_Channels/-anzBwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22isotropic+radiator%22.

- ↑ The angle brackets indicate the average over a cycle, since the power radiated by a sinusoidal acoustic or electromagnetic source varies sinusoidally with time

- ↑ Carr, Joseph J. (1996). Microwave and Communications Technology. Newnes. pp. 171. ISBN 0750697075. https://books.google.com/books?id=ic_3_VRgPhMC&dq=%22isotropic+radiator%22&pg=PA171.

- ↑ Milonni, Peter W. (2019). An Introduction to Quantum Optics and Quantum Fluctuations. Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 118. ISBN 9780192566119. https://books.google.com/books?id=efeEDwAAQBAJ&dq=%22isotropic+radiator%22&pg=PA118.

- ↑ Remsburg, Ralph (2011). Advanced Thermal Design of Electronic Equipment. Springer Science and Business Media. pp. 534. ISBN 978-1441985095. https://books.google.com/books?id=gQ3lBwAAQBAJ&dq=isotropic+sound+radiator&pg=PA534.

- ↑ Pawsey, J.L.; Bracewell, R.N. (1955). Radio Astronomy. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 23–24. https://archive.org/stream/RadioAstronomy_682/PawseyBracewell-RadioAstronomy#page/n35.

- ↑ Rohlfs, Kristen; Wilson, T.L. (2013). Tools of Radio Astronomy, 4th Edition. Springer Science and Business Media. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-3662053942. https://books.google.com/books?id=xvvuCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA134.

- ↑ Condon, J.J.; Ransom, S.M. (2016). "Antenna fundamentals". https://www.cv.nrao.edu/course/astr534/AntennaTheory.html.

External links

- Isotropic Radiators, Matzner and McDonald, arXiv Antennas

- Antennas D.Jefferies

- isotropic radiator AMS Glossary

- U.S. Patent 4,130,023 – Method and apparatus for testing and evaluating loudspeaker performance

- Non Lethal Concepts – Implications for Air Force Intelligence Published Aerospace Power Journal, Winter 1994

- Glossary

- Cosmic Microwave Background – Introduction

- Isotropic Radiators Holon Academic Institute of Technology

|