Physics:Lorentz scalar

In a relativistic theory of physics, a Lorentz scalar is an expression, formed from items of the theory, which evaluates to a scalar, invariant under any Lorentz transformation. A Lorentz scalar may be generated from e.g., the scalar product of vectors, or from contracting tensors of the theory. While the components of vectors and tensors are in general altered under Lorentz transformations, Lorentz scalars remain unchanged.

A Lorentz scalar is not always immediately seen to be an invariant scalar in the mathematical sense, but the resulting scalar value is invariant under any basis transformation applied to the vector space, on which the considered theory is based. A simple Lorentz scalar in Minkowski spacetime is the spacetime distance ("length" of their difference) of two fixed events in spacetime. While the "position"-4-vectors of the events change between different inertial frames, their spacetime distance remains invariant under the corresponding Lorentz transformation. Other examples of Lorentz scalars are the "length" of 4-velocities (see below), or the Ricci curvature in a point in spacetime from general relativity, which is a contraction of the Riemann curvature tensor there.

Simple scalars in special relativity

Length of a position vector

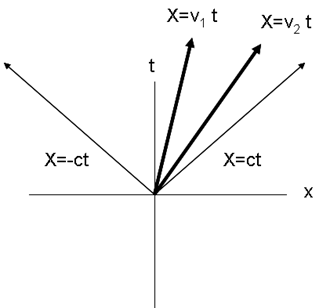

In special relativity the location of a particle in 4-dimensional spacetime is given by [math]\displaystyle{ x^\mu = (ct, \mathbf{x}) }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{v} t }[/math] is the position in 3-dimensional space of the particle, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v} }[/math] is the velocity in 3-dimensional space and [math]\displaystyle{ c }[/math] is the speed of light.

The "length" of the vector is a Lorentz scalar and is given by [math]\displaystyle{ x_{\mu} x^{\mu} = \eta_{\mu \nu} x^{\mu} x^{\nu} = (ct)^2 - \mathbf{x} \cdot \mathbf{x} \ \stackrel{\mathrm{def}}{=}\ (c\tau)^2 }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math] is the proper time as measured by a clock in the rest frame of the particle and the Minkowski metric is given by [math]\displaystyle{ \eta^{\mu\nu} = \eta_{\mu\nu} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 \end{pmatrix}. }[/math] This is a time-like metric.

Often the alternate signature of the Minkowski metric is used in which the signs of the ones are reversed. [math]\displaystyle{ \eta^{\mu\nu} = \eta_{\mu\nu} = \begin{pmatrix} -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}. }[/math] This is a space-like metric.

In the Minkowski metric the space-like interval [math]\displaystyle{ s }[/math] is defined as [math]\displaystyle{ x_{\mu} x^{\mu} = \eta_{\mu \nu} x^{\mu} x^{\nu} = \mathbf{x} \cdot \mathbf{x} - (ct)^2 \ \stackrel{\mathrm{def}}{=}\ s^2. }[/math]

We use the space-like Minkowski metric in the rest of this article.

Length of a velocity vector

The velocity in spacetime is defined as [math]\displaystyle{ v^{\mu} \ \stackrel{\mathrm{def}}{=}\ {dx^{\mu} \over d\tau} = \left( c {dt \over d\tau}, {dt \over d\tau}{d\mathbf{x} \over dt} \right) = \left( \gamma c, \gamma { \mathbf{v} } \right) = \gamma \left( c, { \mathbf{v} } \right) }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \ \stackrel{\mathrm{def}}{=}\ { 1 \over {\sqrt {1 - { {\mathbf{v} \cdot \mathbf{v}} \over c^2} } } } . }[/math]

The magnitude of the 4-velocity is a Lorentz scalar, [math]\displaystyle{ v_\mu v^\mu = -c^2\,. }[/math]

Hence, [math]\displaystyle{ c }[/math] is a Lorentz scalar.

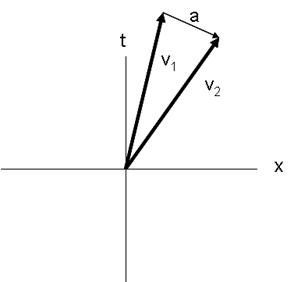

Inner product of acceleration and velocity

The 4-acceleration is given by [math]\displaystyle{ a^{\mu} \ \stackrel{\mathrm{def}}{=}\ {dv^{\mu} \over d\tau}. }[/math]

The 4-acceleration is always perpendicular to the 4-velocity [math]\displaystyle{ 0 = {1 \over 2} {d \over d\tau} \left( v_\mu v^\mu \right) = {d v_\mu \over d\tau} v^\mu = a_\mu v^\mu. }[/math]

Therefore, we can regard acceleration in spacetime as simply a rotation of the 4-velocity. The inner product of the acceleration and the velocity is a Lorentz scalar and is zero. This rotation is simply an expression of energy conservation: [math]\displaystyle{ {d E \over d\tau} = \mathbf{F} \cdot \mathbf{v} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] is the energy of a particle and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{F} }[/math] is the 3-force on the particle.

Energy, rest mass, 3-momentum, and 3-speed from 4-momentum

The 4-momentum of a particle is [math]\displaystyle{ p^\mu = m v^\mu = \left( \gamma m c, \gamma m \mathbf{v} \right) = \left( \gamma m c, \mathbf{p} \right) = \left( \frac E c , \mathbf{p} \right) }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] is the particle rest mass, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{p} }[/math] is the momentum in 3-space, and [math]\displaystyle{ E = \gamma m c^2 }[/math] is the energy of the particle.

Energy of a particle

Consider a second particle with 4-velocity [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] and a 3-velocity [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{u}_2 }[/math]. In the rest frame of the second particle the inner product of [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] is proportional to the energy of the first particle [math]\displaystyle{ p_\mu u^\mu = - E_1 }[/math] where the subscript 1 indicates the first particle.

Since the relationship is true in the rest frame of the second particle, it is true in any reference frame. [math]\displaystyle{ E_1 }[/math], the energy of the first particle in the frame of the second particle, is a Lorentz scalar. Therefore, [math]\displaystyle{ E_1 = \gamma_1 \gamma_2 m_1 c^2 - \gamma_2 \mathbf{p}_1 \cdot \mathbf{u}_2 }[/math] in any inertial reference frame, where [math]\displaystyle{ E_1 }[/math] is still the energy of the first particle in the frame of the second particle.

Rest mass of the particle

In the rest frame of the particle the inner product of the momentum is [math]\displaystyle{ p_\mu p^\mu = -(mc)^2 \,. }[/math]

Therefore, the rest mass (m) is a Lorentz scalar. The relationship remains true independent of the frame in which the inner product is calculated. In many cases the rest mass is written as [math]\displaystyle{ m_0 }[/math] to avoid confusion with the relativistic mass, which is [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma m_0 }[/math].

3-momentum of a particle

Note that [math]\displaystyle{ \left( \frac{p_{\mu} u^\mu}{c} \right)^2 + p_{\mu} p^{\mu} = {E_1^2 \over c^2} - (mc)^2 = \left( \gamma_1^2 - 1 \right) (mc)^2 = \gamma_1^2 {\mathbf{v}_1 \cdot \mathbf{v}_1} m^2 = \mathbf{p}_1 \cdot \mathbf{p}_1. }[/math]

The square of the magnitude of the 3-momentum of the particle as measured in the frame of the second particle is a Lorentz scalar.

Measurement of the 3-speed of the particle

The 3-speed, in the frame of the second particle, can be constructed from two Lorentz scalars [math]\displaystyle{ v_1^2 = \mathbf{v}_1 \cdot \mathbf{v}_1 = \frac { \mathbf{p}_1 \cdot \mathbf{p}_1 } { E_1^2 } c^4. }[/math]

More complicated scalars

Scalars may also be constructed from the tensors and vectors, from the contraction of tensors (such as [math]\displaystyle{ F_{\mu\nu}F^{\mu\nu} }[/math]), or combinations of contractions of tensors and vectors (such as [math]\displaystyle{ g_{\mu\nu}x^{\mu}x^{\nu} }[/math]).

References

- Misner, Charles; Thorne, Kip S.; Wheeler, John Archibald (1973). Gravitation. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.

- Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz, E. M. (1975). Classical Theory of Fields (Fourth Revised English ed.). Oxford: Pergamon. ISBN 0-08-018176-7.

External links

|