Place:Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (1936–1991)

Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic (1919–1936)

| |

|---|---|

| 1919–1991 1941–1944: German and Romanian occupation | |

Motto: Пролетарі всіх країн, єднайтеся! (Ukrainian) "Proletari vsikh krayin, yednaitesia!" (transliteration) "Workers of the world, unite!" | |

Anthem: Державний гімн Української Радянської Соціалістичної Республіки (Ukrainian) Derzhavnyy himn Ukrayins'koyi Radyans'koyi Sotsialistychnoyi Respubliky (transliteration) | |

Location of the Ukrainian SSR within the Soviet Union from 1954 | |

| Status | Puppet state of Soviet Russia (1919–1922) Union Republic of the USSR (1922–1990) Union Republic with priority of Ukrainian legislation (1990–1991) |

| Capital | Kharkiv (1919–1934)[1] Kiev (1934–1991)[2] |

| Common languages | Ukrainian (official since 1990)a[3] Languages: Ukrainian · Russian[4] |

| Government | Soviet republic |

| First Secretary | |

• 1918–1919 | Emanuel Kviring (first) |

• 1990–1991 | Stanislav Hurenko (last) |

| Head of state | |

• 1919–1938 | Grigory Petrovsky (first) |

• 1990–1991 | Leonid Kravchuk (last) |

| Head of government | |

• 1919–1923 | Christian Rakovsky (first) |

• 1988–1991 | Vitold Fokin (last) |

| Legislature | Supreme Soviet[5] |

| Historical era | 20th century |

• Declaration of the Ukrainian Soviet republic | 10 March 1919 |

• Admitted to USSR | 30 December 1922 |

• Annexation of Western Ukraine from Poland | 15 November 1939 |

• Admitted to the United Nations | 24 October 1945 |

• Priority of Ukrainian laws declared, Soviet laws partially abolished | 10 July 1990 |

• Declaration of independence, Ukrainian SSR renamed to Ukraine | 24 August 1991 |

• Ukrainian independence referendum | 1 December 1991 |

• Ratification of agreement to dissolve the Soviet Union | 10 December 1991 |

• Dissolution of the Soviet Union (Ukraine's independence formally recognized) | 26 December 1991 |

• Soviet government officially abolished (New constitution) | 28 June 1996 |

| Area | |

| 1989 census | 603,700 km2 (233,100 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1989 census | 51,706,746 |

| Currency | Soviet ruble (karbovanets) |

| Calling code | 7 03/04/05/06 |

| Today part of | |

| |

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (Ukrainian SSR or UkrSSR or UkSSR; Ukrainian: Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, Украї́нська РСР, УРСР ; Russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респу́блика, Украи́нская ССР , УССР ; see "Name" section below), also known as the Soviet Ukraine, was one of the constituent republics of the Soviet Union from the Union's inception in 1922 to its breakup in 1991.[6] The republic was governed by the Communist Party of Ukraine as a unitary one-party socialist soviet republic.

The Ukrainian SSR was a founding member of the United Nations ,[7] although it was legally represented by the All-Union state in its affairs with countries outside of the Soviet Union. Upon the Soviet Union's dissolution and perestroika, the Ukrainian SSR was transformed into the modern nation-state and renamed itself to Ukraine .[8]

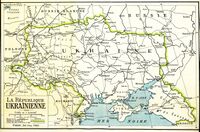

Throughout its 72-year history, the republic's borders changed many times, with a significant portion of what is now Western Ukraine being annexed by Soviet forces in 1939 from the Republic of Poland, and the addition of Zakarpattia in 1946. From the start, the eastern city of Kharkiv served as the republic's capital. However, in 1934, the seat of government was subsequently moved to the city of Kiev, Ukraine's historic capital. Kiev remained the capital for the rest of the Ukrainian SSR's existence, and remained the capital of independent Ukraine after the breakup of the Soviet Union.

Geographically, the Ukrainian SSR was situated in Eastern Europe to the north of the Black Sea, bordered by the Soviet republics of Moldavia, Byelorussia, and the Russian SFSR. The Ukrainian SSR's border with Czechoslovakia formed the Soviet Union's western-most border point. According to the Soviet Census of 1989 the republic had a population of 51,706,746 inhabitants, which fell sharply after the breakup of the Soviet Union.

For most of its existence, it ranked second only to the Russian SFSR in population, economic and political power.

Name

The name "Ukraine" (Latin: Vkraina) is a subject of debate. It is often perceived as being derived from the Slavic word "okraina", meaning "border land". It was first used to define part of the territory of Kievan Rus' (Ruthenia) in the 12th century, at which point Kiev was the capital of Rus' (Russian land). The name has been used in a variety of ways since the twelfth century. For example, Zaporozhian Cossacks called their Hetmanate "Ukraine", which can be translated as "Our country" or "our land".

Within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the name carried unofficial status for eastern parts of bigger Kiev Voivodeship and was overshadowed by more common Little Poland.

Since the partition of Poland, the name has generally disappeared and was replaced with the Russian colonial name of Little Russia.

The idea of Ukraine as borderland crept in the English language at some point. Therefore, while Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union, Anglophones referred to the Ukrainian SSR as "The Ukraine".[9] However, since the fall of the Soviet Union, the officially recognized name is simply "Ukraine".[citation needed] The definite article may imply that it is a land or general geographic area with unidentified borders.[9]

History

After the abdication of the tsar and the start of the process of destruction of the Russian Empire many people in Ukraine wished to establish a Ukrainian Republic. During a period of civil war from 1917 to 1923 many factions claiming themselves governments of the newly born republic were formed, each with supporters and opponents. The two most prominent of them were a government in Kiev (called the Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR)) and a government in Kharkiv (called the Ukrainian Soviet Republic (USR)). The Kiev-based UPR was internationally recognized and supported by the Central powers following the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, whereas the Kharkiv-based USR was solely supported by Soviet Russian forces, while neither the UPR nor the USR were supported by the White Russian forces that remained.[citation needed]

The conflict between the two competing governments, known as the Ukrainian–Soviet War, was part of the ongoing Russian Civil War, as well as a struggle for national independence, which ended with the pro-independence Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) being annexed into a new Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic (Ukrainian: УСРР), western Ukraine being absorbed into the Second Polish Republic, and the newly stable Ukraine becoming a founding member of the Soviet Union. This government of the Soviet Ukrainian Republic was founded on 24–25 December 1917. In its publications it names itself either the "Republic of Soviets of Workers', Soldiers', and Peasants' Deputies"[10] or the "Ukrainian People's Republic of Soviets".[11]

The 1917 republic, however, was only recognised by another non-recognised country, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, and with the signing of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty was ultimately defeated by mid-1918 and eventually dissolved. The last session of the government took place in the city of Taganrog. In July 1918, the former members of the government formed the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine, the constituent assembly of which took place in Moscow. With the defeat of the Central Powers in World War I, Bolshevik Russia resumed its hostilities towards the Ukrainian People's Republic fighting for Ukrainian independence and organised another Soviet government in Kursk, Russia. On 10 March 1919, according to the 3rd Congress of Soviets in Ukraine (conducted 6–10 March 1919) the name of the state was changed to the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic (abbreviated "УСРР" in Ukrainian as opposed to the later "УРСР").[11]

After the ratification of the 1936 Soviet Constitution, the names of all Soviet republics were changed, transposing the second ("socialist") and third ("soviet" or "radianska" in Ukrainian) words. In accordance, on 5 December 1936, the 8th Extraordinary Congress Soviets in Soviet Union changed the name of the republic to the "Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic", which was ratified by the 14th Extraordinary Congress of Soviets in Ukrainian SSR on 31 January 1937.[11]

During its existence, the Ukrainian SSR was commonly referred to as "Ukraine" or "the Ukraine".[citation needed]

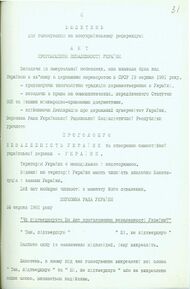

On 24 August 1991, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic declared independence and the legal name of the republic was changed to the Ukraine on 17 September 1991. Since the adoption of the Constitution of Ukraine in June 1996, the country became known simply as Ukraine , which is the name used to this day.[citation needed]

Founding: 1917–1922

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, several factions sought to create an independent Ukrainian state, alternately cooperating and struggling against each other. Numerous more or less socialist-oriented factions participated in the formation of the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR) among which were Bolsheviks, Mensheviks, Socialists-Revolutionaries, and many others. The most popular faction was initially the local Socialist Revolutionary Party that composed the local government together with Federalists and Mensheviks. The Bolsheviks boycotted any government initiatives most of the time, instigating several armed riots in order to establish the Soviet power without any intent for consensus.[citation needed]

Immediately after the October Revolution in Petrograd, Bolsheviks instigated the Kiev Bolshevik Uprising to support the Revolution and secure Kiev. Due to a lack of adequate support from the local population and anti-revolutionary Central Rada, however, the Kiev Bolshevik group split. Most moved to Kharkiv and received the support of the eastern Ukrainian cities and industrial centers. Later, this move was regarded as a mistake by some of the People's Commissars (Yevgenia Bosch). They issued an ultimatum to the Central Rada on 17 December to recognise the Soviet regime of which the Rada was very critical. The Bolsheviks convened a separate congress and declared the first Soviet Republic of Ukraine on 24 December 1917 claiming the Central Rada and its supporters outlaws that need to be eradicated. Warfare ensued against the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR) for the installation of the Soviet regime in the country and with the direct support from Union of Soviet Socialist Republics the Ukrainian National forces were practically overran. The government of Ukraine appealed to foreign capitalists, finding the support in the face of the Central Powers as the others refused to recognise it. After the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the Russian SFSR yielded all the captured Ukrainian territory as the Bolsheviks were forced out of Ukraine. The government of the Soviet Ukraine was dissolved after its last session on 20 November 1918.[citation needed]

After re-taking Kharkiv in February 1919, a second Soviet Ukrainian government was formed, consisting mostly of Russians, Jews, and non-Ukrainians. The government enforced Russian policies that did not adhere to local needs. 3,000 workers were dispatched from Russia to take grain from local farms by force if necessary to feed Russian cities, and were met with resistance. The Ukrainian language was also censured from administrative and educational use. Eventually fighting both White forces in the east and republic forces in the west, Lenin ordered the liquidation of the second Soviet Ukrainian government in August 1919.[12]

Eventually, after the creation of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine in Moscow, a third Ukrainian Soviet government was formed on 21 December 1919 that initiated new hostilities against Ukrainian nationalists as they lost their military support from the defeated Central Powers. Eventually, the Red Army ended up controlling much of the Ukrainian territory after the Polish-Soviet Peace of Riga. On 30 December 1922, along with the Russian, Byelorussian, and Transcaucasian republics, the Ukrainian SSR was one of the founding members of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).[citation needed]

Interwar years: 1922–1939

In 1932, the aggressive agricultural policies of Joseph Stalin 's regime resulted in one of the largest national catastrophes in the modern history for the Ukrainian nation. A famine known as the Holodomor caused a direct loss of human life estimated between 2.6 million[13][14] to 10 million.[15] Some scholars and "International Commission of Inquiry Into the 1932–33 Famine in Ukraine"[16] state that this was an act of genocide, while other scholars state that the catastrophe was caused by gross mismanagement and failure to collectivise on a voluntary basis.[citation needed]. The General Assembly of the UN has stopped shy of recognizing the Holodomor as genocide, calling it a "great tragedy" as a compromise between tense positions of United Kingdom, United States, Russia, and Ukraine on the matter, while many nations went on individually to accepted it as such.[citation needed]

Between 1934 and 1939 prominent representatives of Ukrainian culture were executed.[citation needed]

World War II: 1939–1945

In September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland and occupied Galician lands inhabited by Ukrainians, Poles and Jews adding it to the territory of the Ukrainian SSR. In 1945, these lands were permanently annexed, and the Transcarpathia region was added as well, by treaty with the post-war administration of Czechoslovakia. Following eastward Soviet retreat in 1941, Ufa became the wartime seat of the Soviet Ukrainian government.[citation needed]

Post-war years: 1945–1953

While World War II (called the Great Patriotic War by the Soviet government) did not end before May 1945, the Germans were driven out of Ukraine between February 1943 and October 1944. The first task of the Soviet authorities was to reestablish political control over the republic which had been entirely lost during the war. This was an immense task, considering the widespread human and material losses. During World War II the Soviet Union lost around 11 million combatants and around 7 million civilians, of these, 4.1 million and 1.4 were Ukrainian civilians and military personnel. Also, an estimated 3.9 million Ukrainians were evacuated to the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic during the war, and 2.2 million Ukrainians were sent to forced labour camps by the Germans.[citation needed]

The material devastation was huge; Adolf Hitler's orders to create "a zone of annihilation" in 1943, coupled with the Soviet military's scorched-earth policy in 1941, meant Ukraine lay in ruins. These two policies led to the destruction of 28 thousand villages and 714 cities and towns. 85 percent of Kiev's city centre was destroyed, as was 70 percent of the city centre of the second-largest city in Ukraine, Kharkiv. Because of this, 19 million people were left homeless after the war.[17] The republic's industrial base, as so much else, was destroyed.[18] The Soviet government had managed to evacuate 544 industrial enterprises between July and November 1941, but the rapid German advance led to the destruction or the partial destruction of 16,150 enterprises. 27,910 thousand collective farms, 1,300 machine tractor stations and 872 state farms were destroyed by the Germans.[19]

While the war brought to Ukraine an enormous physical destruction, victory also led to territorial expansion. As a victor, the Soviet Union gained new prestige and more land. The Ukrainian border was expanded to the Curzon Line. Ukraine was also expanded southwards, near the area Izmail, previously part of Romania.[19] An agreement was signed by the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia whereby Carpathian Ruthenia was handed over to Ukraine.[20] The territory of Ukraine expanded by 167,000 square kilometres (64,500 sq mi) and increased its population by an estimated 11 million.[21]

After World War II, amendments to the Constitution of the Ukrainian SSR were accepted, which allowed it to act as a separate subject of international law in some cases and to a certain extent, remaining a part of the Soviet Union at the same time. In particular, these amendments allowed the Ukrainian SSR to become one of founding members of the United Nations (UN) together with the Soviet Union and the Byelorussian SSR. This was part of a deal with the United States to ensure a degree of balance in the General Assembly, which, the USSR opined, was unbalanced in favor of the Western Bloc. In its capacity as a member of the UN, the Ukrainian SSR was an elected member of the United Nations Security Council in 1948–1949 and 1984–1985.[citation needed]

Khrushchev and Brezhnev: 1953–1985

When Stalin died on 5 March 1953 the collective leadership of Khrushchev, Georgy Malenkov, Vyacheslav Molotov and Lavrentiy Beria took power and a period of de-Stalinisation began.[22] Change came as early as 1953, when officials were allowed to criticise Stalin's policy of russification. The Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine (CPU) openly criticised Stalin's russification policies in a meeting in June 1953. On 4 June 1953, Oleksii Kyrychenko succeeded Leonid Melnikov as First Secretary of the CPU; this was significant since Kyrychenko was the first ethnic Ukrainian to lead the CPU since the 1920s. The policy of de-Stalinisation took two main features, that of centralisation and decentralisation from the centre. In February 1954 the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) transferred Crimea as a gift to Ukraine from the Russians; even if only 22 percent of the Crimean population were ethnic Ukrainian.[23] 1954 also witnessed the massive state-organised celebration of the 300th anniversary of the Treaty of Pereyaslav; the treaty which brought Ukraine under Russian rule three centuries before. The event was celebrated to prove the old and brotherly love between Ukrainians and Russians, and proof of the Soviet Union as a "family of nations"; it was also another way of legitimising Marxism–Leninism.[24]

The "Thaw" – the policy of deliberate liberalisation – was characterised by four points: amnesty for all those convicted of state crime during the war or the immediate post-war years; amnesties for one-third of those convicted of state crime during Stalin's rule; the establishment of the first Ukrainian mission to the United Nations in 1958; and the steady increase of Ukrainians in the rank of the CPU and government of the Ukrainian SSR. Not only were the majority of CPU Central Committee and Politburo members ethnic Ukrainians, three-quarters of the highest ranking party and state officials were ethnic Ukrainians too. The policy of partial Ukrainisation also led to a cultural thaw within Ukraine.[24]

In October 1964, Khrushchev was deposed by a joint Central Committee and Politburo plenum and succeeded by another collective leadership, this time led by Leonid Brezhnev, born in Ukraine, as First Secretary and Alexei Kosygin as Chairman of the Council of Ministers.[25] Brezhnev's rule would be marked by social and economic stagnation, a period often referred to as the Era of Stagnation.[26] The new regime introduced the policy of rastsvet, sblizhenie and sliianie ("flowering", "drawing together" and "merging"/"fusion"), which was the policy of uniting the different Soviet nationalities into one Soviet nationality by merging the best elements of each nationality into the new one. This policy turned out to be, in fact, the reintroduction of the russification policy.[27] The reintroduction of this policy can be explained by Khrushchev's promise of communism in 20 years; the unification of Soviet nationalities would take place, according to Vladimir Lenin, when the Soviet Union reached the final stage of communism, also the final stage of human development. Some all-Union Soviet officials were calling for the abolition of the "pseudosovereign" Soviet republics, and the establishment of one nationality. Instead of introducing the ideologic concept of the Soviet Nation, Brezhnev at the 24th Party Congress talked about "a new historical community of people – the Soviet people",[27] and introduced the ideological tenant of Developed socialism, which postponed communism.[28] When Brezhnev died in 1982, he was succeeded by Yuri Andropov, who died quickly after taking power. Andropov was succeeded by Konstantin Chernenko, who ruled for little more than a year. Chernenko was succeeded by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985.[29]

Gorbachev and dissolution: 1985–1991

Gorbachev's policies of perestroika and glasnost (English: restructuring and openness) failed to reach Ukraine as early as other Soviet republics because of Volodymyr Shcherbytsky, a conservative communist appointed by Brezhnev and the First Secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party, who resigned from his post in 1989.[30] The Chernobyl disaster of 1986, the russification policies, and the apparent social and economic stagnation led several Ukrainians to oppose Soviet rule. Gorbachev's policy of perestroika was also never introduced into practice, 95 percent of industry and agriculture was still owned by the Soviet state in 1990. The talk of reform, but the lack of introducing reform into practice, led to confusion which in turn evolved into opposition to the Soviet state itself.[31] The policy of glasnost, which ended state censorship, led the Ukrainian diaspora to reconnect with their compatriots in Ukraine, the revitalisation of religious practices by destroying the monopoly of the Russian Orthodox Church and led to the establishment of several opposition pamphlets, journals and newspapers.[32]

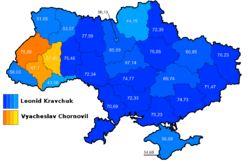

Following the failed August Coup in Moscow on 19–21 August 1991, the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR declared independence on 24 August 1991, which renamed the Ukrainian SSR to Ukraine . The result of the 1991 independence referendum held on 1 December 1991 proved to be a surprise. An overwhelming majority, 92.3%, voted for independence. The referendum carried in the majority of all oblasts. Notably, the Crimea, which had originally been a territory of the RSFSR until 1954, supported the referendum by a 54 percent majority. Over 80 percent of the population of Eastern Ukraine voted for independence. Ukraine's independence from the Soviet Union led to an almost immediate recognition from the international community. Ukraine's new-found independence was the first time in the 20th century that Ukrainian independence had not been attempted without either foreign intervention or civil war. In the 1991 Ukrainian presidential election 62 percent of Ukrainians voted for Leonid Kravchuk.[33] The secession of the second most powerful republic in the Soviet Union ended any realistic chance of the Soviet Union staying together even on a limited scale. The Soviet Union formally dissolved three weeks after Ukraine's secession.[citation needed]

Politics and government

The Ukraine's system of government was based on a one-party communist system ruled by the Communist Party of Ukraine, a part of the Communist Party of Soviet Union (KPSS). The republic was one of 15 constituent republics composing the Soviet Union from its entry into the union in 1922 till its dissolution in 1991. All of the political power and authority in the USSR was in the hands of Communist Party authorities, with little real power being concentrated in official government bodies and organs. In such a system, lower-level authorities directly reported to higher level authorities and so on, with the bulk of the power being held at the highest echelons of the Communist Party.[34]

Originally, the legislative authority was vested in the Central Executive Committee of Ukraine that for many years was headed by Grigoriy Petrovsky. Soon after publishing the Stalin Constitution, the Central Executive Committee was transformed into the Supreme Soviet, which consisted of 450 deputies.[note 1] The Supreme Soviet had the authority to enact legislation, amend the constitution, adopt new administrative and territorial boundaries, adopt the budget, and establish political and economic development plans.[35] In addition, parliament also had to authority to elect the republic's executive branch, the Council of Ministers as well as the power to appoint judges to the Supreme Court. Legislative sessions were short and were conducted for only a few weeks out of the year. In spite of this, the Supreme Soviet elected the Presidium, the Chairman, 3 deputy chairmen, a secretary, and couple of other government members to carry out the official functions and duties in between legislative sessions.[35] The Presidium was a powerful position in the republic's higher echelons of power, and could nominally be considered the equivalent of head of state,[35] although most executive authority would be concentrated in the Communist Party's politburo and its First Secretary.

Full universal suffrage was granted for all eligible citizens aged 18 and over, excluding prisoners and those deprived of freedom. Although they could not be considered free and were of a symbolic nature, elections to the Supreme Soviet were contested every five years. Nominees from electoral districts from around the republic, typically consisting of an average of 110,000 inhabitants, were directly chosen by party authorities,[35] providing little opportunity for political change, since all political authority was directly subordinate to the higher level above it.

With the beginning of Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev's perestroika reforms towards the mid-late 1980s, electoral reform laws were passed in 1989, liberalising the nominating procedures and allowing multiple candidates to stand for election in a district. Accordingly, the first relatively free elections[36] in the Ukrainian SSR were contested in March 1990. 111 deputies from the Democratic Bloc, a loose association of small pro-Ukrainian and pro-sovereignty parties and the instrumental People's Movement of Ukraine (colloquially known as Rukh in Ukrainian) were elected to the parliament.[37] Although the Communist Party retained its majority with 331 deputies, large support for the Democratic Bloc demonstrated the people's distrust of the Communist authorities, which would eventually boil down to Ukrainian independence in 1991.

Ukraine is the legal successor of the Ukrainian SSR and it stated to fulfill "those rights and duties pursuant to international agreements of Union SSR which do not contradict the Constitution of Ukraine and interests of the Republic" on 5 October 1991.[38] After Ukrainian independence the Ukrainian SSR's parliament was changed from Supreme Soviet to its current name Verkhovna Rada, the Verkhovna Rada is still Ukraine's parliament.[5][39] Ukraine also has refused to recognize exclusive Russian claims to succession of the Soviet Union and claimed such status for Ukraine as well, which was stated in Articles 7 and 8 of On Legal Succession of Ukraine, issued in 1991. Following independence, Ukraine has continued to pursue claims against the Russia in foreign courts, seeking to recover its share of the foreign property that was owned by the Soviet Union. It also retained its seat in the United Nations , held since 1945.

Foreign relations

On the international front, the Ukrainian SSR, along with the rest of the 15 republics, virtually had no say in their own foreign affairs. It is, however, important to note that in 1944 the Ukrainian SSR was permitted to establish bilateral relations with countries and maintain its own standing army.[34] This clause was used to permit the republic's membership in the United Nations . Accordingly, representatives from the "Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic" and 50 other nations founded the UN on 24 October 1945. In effect, this provided the Soviet Union (a permanent Security Council member with veto powers) with another vote in the General Assembly.[note 2] The latter aspect of the 1944 clauses, however, was never fulfilled and the republic's defense matters were managed by the Soviet Armed Forces and the Defense Ministry. Another right that was granted but never used until 1991 was the right of the Soviet republics to secede from the union,[40] which was codified in each of the Soviet constitutions. Accordingly, Article 69 of the Constitution of the Ukrainian SSR stated: "The Ukrainian SSR retains the right to willfully secede from the USSR."[41] However, a republic's theoretical secession from the union was virtually impossible and unrealistic[34] in many ways until after Gorbachev's perestroika reforms.

The Ukrainian SSR was a member of the UN Economic and Social Council, UNICEF, International Labour Organization, Universal Postal Union, World Health Organization, UNESCO, International Telecommunication Union, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, World Intellectual Property Organization and the International Atomic Energy Agency. It was not separately a member of the Warsaw Pact, Comecon, the World Federation of Trade Unions and the World Federation of Democratic Youth.

Administrative divisions

Legally, the Soviet Union and its fifteen union republics constituted a federal system, but the country was functionally a highly centralised state, with all major decision-making taking place at the Kremlin, the capital and seat of government of the country. The constituent republic were essentially unitary states, with lower levels of power being directly subordinate to higher ones. Throughout its 72-year existence, the administrative divisions of the Ukrainian SSR changed numerous times, often incorporating regional reorganisation and annexation on the part of Soviet authorities during World War II.

The most common administrative division was the oblast (province), of which there were 25 upon the republic's independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Provinces were further subdivided into raions (districts) which numbered 490. The rest of the administrative division within the provinces consisted of cities, urban-type settlements, and villages. Cities in the Ukrainian SSR were a separate exception, which could either be subordinate to either the provincial authorities themselves or the district authorities of which they were the administrative center. Two cities, the capital Kiev, and Sevastopol in Crimea, treated separately because it housed an underground nuclear submarine base, were designated "cities with special status." This meant that they were directly subordinate to the central Ukrainian SSR authorities and not the provincial authorities surrounding them.

Historical formation

However, the history of administrative divisions in the republic was not so clear cut. At the end of the World War I in 1918, Ukraine was invaded by the Soviet Russia as the Russian puppet government of the Ukrainian SSR and without official declaration it ignited the Ukrainian–Soviet War. Government of the Ukrainian SSR from very beginning was managed by the Communist Party of Ukraine that was created in Moscow and was originally formed out of the Bolshevik organisational centers in Ukraine. Occupying the eastern city of Kharkiv, the Soviet forces chose it as the republic's seat of government, colloquially named in the media as "Kharkov – Pervaya Stolitsa (the first capital)" with implication to the era of Soviet regime.[42] Kharkiv was also the city where the first Soviet Ukrainian government was created in 1917 with strong support from Russian SFSR authorities. However, in 1934, the capital was moved from Kharkiv to Kiev, which remains the capital of Ukraine today, although at first Kharkiv retained some government offices and buildings for some time after the move.

During the 1930s, there were significant numbers of ethnic minorities living within the Ukrainian SSR. National Districts were formed as separate territorial-administrative units within higher-level provincial authorities. Districts were established for the republic's three largest minority groups, which were the Jews, Russians, and Poles.[43] Other ethnic groups, however, were allowed to petition the government for their own national autonomy. In 1924 on the territory of Ukrainian SSR was formed the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. Upon the 1940 conquest of Bessarabia and Bukovina by Soviet troops the Moldavian ASSR was passed to the newly formed Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, while Budzhak and Bukovina were secured by the Ukrainian SSR. Following the creation of the Ukrainian SSR significant numbers of ethnic Ukrainians found themselves living outside the Ukrainian SSR.[44] In 1920s the Ukrainian SSR was forced to cede several territories to Russia in Severia, Sloboda Ukraine and Azov littoral including such cities like Belgorod, Taganrog and Starodub. In the 1920s the administration of the Ukrainian SSR insisted in vain on reviewing the border between the Ukrainian Soviet Republics and the Russian Soviet Republic based on the 1926 First All-Union Census of the Soviet Union that showed that 4.5 millions of Ukrainians were living on Russian territories bordering Ukraine.[44] A forced end to Ukrainisation in southern Russian Soviet Republic led to a massive decline of reported Ukrainians in these regions in the 1937 Soviet Census.[44]

Upon signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Nazi Germany and Soviet Union partitioned Poland and its Eastern Borderlands were secured by the Soviet buffer republics with Ukraine securing the territory of Eastern Galicia. The Soviet September Polish campaign in Soviet propaganda was portrayed as the Golden September for Ukrainian as unification of Ukrainian lands on both banks of Zbruch River.

Economy

Agriculture

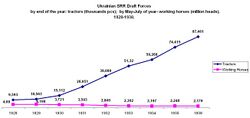

In 1945, agriculture was only 40 percent of the 1940 level, even though the republic's territorial expansion had "increased the amount of arable land."[45] In contrast to the remarkable growth in the industrial sector,[46] agriculture continued in Ukraine, as in the rest of the Soviet Union, the economy's achilles heel. Despite the human losses which had taken place during the Collectivisation of agriculture in the Soviet Union, but especially Ukraine, Soviet planners still believed in the strength of collective farming. The old system was reestablished; the numbers of collective farms in Ukraine increased from 28 thousand in 1940 to 33 thousand in 1949, literally 45 million hectares, the numbers of state farms barely increased, standing at 935 in 1950, which stood at 12.1 million hectares. By the end of the Fourth Five-Year Plan (in 1950) and the Fifth Five-Year Plan (in 1955), agricultural output was still far lower than the 1940 level. The slow changes in agriculture can be explained by the low productivity in collective farms, and bad weather conditions in which the Soviet planning system could not effectively respond to. Grain for human consumption in the post-war years decreased, this in turn led to frequent and severe food shortages.[47]

The increase of agricultural production was tremendous, however, the Soviet-Ukrainians still experienced food shortages due to the inefficiencies of a highly centralised economy. During the peak of Soviet-Ukrainian agriculture output in the 1950s and early-to-mid-1960s, human consumption in Ukraine, and the rest of the Soviet Union, actually experienced short intervals of decrease. There are many reasons for this inefficiency, but its origins can be traced back to the one purchaser and producer market system created by Joseph Stalin .[48] Khrushchev tried to improve the agricultural situation in the Soviet Union by expanding the total crop size, for instance, in the Ukrainian SSR alone "the amount of land planted with corn grew by 600 percent." At the height of this policy, between 1959 and 1963, one-third of Ukrainian arable land was planted with such a crop. This policy decreased the total production of wheat and rye; this was anticipated by Khrushchev, and the production of wheat and rye was moved to Soviet Central Asia as part of the Virgin Land Campaign. Khrushchev's agricultural policy was a failure, and in 1963, the Soviet Union was forced to import food from abroad. The total level of agricultural productivity in Ukraine decreased sharply during this period, but recovered in the 1970s and 1980s during Leonid Brezhnev's rule.[25]

Industry

During the post-war years, Ukraine's industrial productivity had doubled its pre-war level.[49] In 1945, industrial output was only 26 percent of the 1940 level. The Soviet regime, which still believed in the planned economy, introduced the Fourth Five-Year Plan in 1946. The Fourth Five-Year Plan would prove to be a remarkable success, and can be likened to the "wonders of West German and Japanese reconstruction", but without foreign capital; the Soviet reconstruction is historically an impressive achievement. In 1950 industrial gross output had already surpassed 1940-levels. While the Soviet regime still put more emphasis on heavy industry over light industry, the light industry sector all witnessed good growth ratings. The increase in capital investment and the expansion of the labour force, also benefited Ukraine's economic recovery. In the prewar years, 15.9 percent of the Soviet budget was used on Ukraine, in 1950, during the Fourth Five-Year Plan this had increased to 19.3 percent. The workforce had increased from 1.2 million in 1945 to 2.9 million in 1955; a increase of 33.2 percent over the 1940-level.[45] The end result of this remarkable growth was that by 1955 Ukraine was producing 2.2 times more than in 1940, and the republic was already one of the leading producers of certain commodities in Europe. Ukraine was the largest per capita producer in Europe of pig iron and sugar, and the second-largest per capita producer of the smelting of steel and the mining of iron ore, and was the third largest per capita producer of the mining of coal, in Europe.[47]

From 1965 until the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the industrial growth in Ukraine decreased, and by the 1970s, it started to stagnate. Significant economic decline did not become apparent before the 1970s. During the Fifth Five-Year Plan (1951–1955), industrial development in Ukraine grew by 13.5 percent, while, during the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (1981–1985) industry grew by a modest 3.5 percent. The double digit growth seen in all branches of the economy in the post-war years, had by the 1980s disappeared, and entirely replaced by low growth figures. An ongoing problem throughout the republic's existence was the planner's emphasis on heavy industry over consumer goods.[49]

The urbanisation of Ukrainian society in the post-war years led to an increase in energy consumption. Between 1956 and 1972, to meet this increasing demand, the government built five water reservoirs along the Dnieper River. Aside from improving Soviet-Ukrainian water transport, the reservoirs became the site for new power stations, and hydroelectric energy flourished in Ukraine because of it. The gas industry flourished as well, and Ukraine became the site of the first post-war production of gas in the Soviet Union; by the 1960s Ukraine's biggest gas field was producing 30 percent of the USSR's total gas production. The government was not able to meet the people's ever increasing demand for energy consumption, but by the 1970s, the Soviet government had conceived an intensive nuclear power program. According to the Eleventh Five-Year Plan, the Soviet government would build 8 nuclear power plants by the 1980s in Ukraine. As a result of these efforts, Ukraine became highly diversified in energy consumption.[48]

Religion

Many churches and synagogues were destroyed during the existence of the Ukrainian SSR.[50]

Urbanisation

Urbanisation in post-Stalin Ukraine grew quickly; in 1959 only 25 cities in Ukraine had populations over one hundred thousand, by 1979 the number had grown to 49. During the same period, the growth of cities with a population over one million increased from one to five; Kiev alone nearly doubled its population, from 1.1 million in 1959 to 2.1 million in 1979. This proved a turning point in Ukrainian society: for the first time in Ukraine's history, the majority of ethnic Ukrainians lived in urban areas; 53 percent of the ethnic Ukrainian population did so in 1979. The majority worked in the non-agricultural sector, in 1970 31 percent of Ukrainians engaged in agriculture, in contrast, 63 percent of Ukrainians were industrial workers and white-collar staff. In 1959, 37 percent of Ukrainians lived in urban areas, in 1989 the proportion had increased to 60 percent.[51]

References

Notes

Citations

- ↑ "History" (in Ukrainian). Kharkiv Oblast Government Administration. http://kharkivoda.gov.ua/uk/article/view/id/4/. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ↑ (in Ukrainian) Soviet Encyclopedia of the History of Ukraine. Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR. 1969–1972.

- ↑ Law of Ukraine "About languages of the Ukrainian SSR"

- ↑ Language Policy in the Soviet Union by Lenore Grenoble, Springer Science+Business Media, 2003, ISBN 978-1-4020-1298-3.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples by Paul Robert Magocsi, University of Toronto Press, 2010, ISBN 1442640855

- ↑ Lee, Gary - Soviets Begin Recovery From Disaster's Damage, Washington Post. Published on 27 October 1986. Retrieved on 25 April 2017.

- ↑ "Activities of the Member States - Ukraine". United Nations. https://www.un.org/depts/dhl/unms/ukraine.shtml. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- ↑ "Ukraine: vie politique depuis 1991". Larousse. http://www.larousse.fr/encyclopedie/divers/Ukraine_vie_politique_depuis_1991/187636.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Geoghegan, Tom. "Ukraine or the Ukraine: Why do some country names have 'the'?" BBC News. 7 June 2012.

- ↑ Rumyantsev, Vyacheslav. "Revolution of 1917 in Russia" (in Russian). XRONOS: Worldwide History on the Internet. http://www.hrono.ru/1917ru.html. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic" (in Russian). Guide to the history of the Communist Party and the Soviet Union in 1898. http://www.knowbysight.info/1_UKRA/08983.asp. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ↑ Subtelny, Orest. Ukraine: A History. p. 365. https://books.google.ca/books?id=l5uiWHgRphQC&pg=PA475&dq=soviet+partisans+western+ukraine&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiR5IPEjuTLAhVBlxoKHUuhAcsQ6AEIGzAA#v=onepage&q=365&f=false.

- ↑ France Meslé, Gilles Pison, Jacques Vallin France-Ukraine: Demographic Twins Separated by History, Population and societies, N°413, juin 2005

- ↑ ce Meslé, Jacques Vallin Mortalité et causes de décès en Ukraine au XXè siècle + CDRom ISBN 2-7332-0152-2 CD online data (partially - "Mortality and Causes of Death in Ukraine for the 20th Century". Archived from the original on 12 September 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130912153906/http://www.ined.fr/fichier/t_publication/cdrom_mortukraine/cdrom.htm. Retrieved 5 February 2016.)

- ↑ Shelton, Dinah (2005). Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. Detroit ; Munich: Macmillan Reference, Thomson Gale. pp. 1059. ISBN 0-02-865850-7.

- ↑ Jacob W.F. Sundberg (May 1990). "International Commission of Inquiry Into the 1932–33 Famine in Ukraine. The Final Report (1990)". The Institute of Public and International Law (IOIR). Archived from the original on 4 December 2004. https://web.archive.org/web/20041204224314/http://www.ioir.se/ukrfamine.htm.

- ↑ Magocsi 1996, p. 684.

- ↑ Magocsi 1996, pp. 684–685.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Magocsi 1996, p. 685.

- ↑ Magocsi 1996, p. 687.

- ↑ Magocsi 1996, p. 688.

- ↑ Magocsi 1996, p. 701.

- ↑ Magocsi 1996, pp. 702–703.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Magocsi 1996, p. 703.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Magocsi 1996, p. 708.

- ↑ Magocsi 1996, pp. 708–709.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Magocsi 1996, p. 709.

- ↑ Dowlah, Alex; Elliot, John (1997). The Life and Times of Soviet Socialism. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-275-95629-5.

- ↑ Magocsi 1996, p. 715.

- ↑ Magocsi 1996, p. 717.

- ↑ Magocsi 1996, pp. 718–719.

- ↑ Magocsi 1996, pp. 720–721.

- ↑ Magocsi 1996, p. 724.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Yurchenko, Oleksander (1984). "Constitution of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?AddButton=pages\C\O\ConstitutionoftheUkrainianSovietSocialistRepublic.htm. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 Balan, Borys (1993). "Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?AddButton=pages\S\U\SupremeSovietoftheUkrainianSSR.htm. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ↑ Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. pp. 576. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20080512070738/http://www-history.univer.kharkov.ua/e-library/kalinichenko_textbook/Kalinichenko_10.2.htm. - ↑ The Law of Ukraine on Succession of Ukraine, Verkhovna Rada (5 October 1991).

- ↑ Ukraine. Verkhovna Rada, Library of Congress

- ↑ Subtelny, p. 421.

- ↑ "CONSTITUTION OF THE UKRAINIAN SSR 1978" (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. http://gska2.rada.gov.ua/site/const/istoriya/1978.html. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ↑ "My Kharkiv" (in Ukrainian). Kharkiv Collegium. 2008. http://www.collegium.kharkov.ua/ua/pg/kharkov/character.html. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ↑ Magocsi, Paul Robert (207). Ukraine, An Illustrated HIstory. Seattle: University of Washington Press. pp. 229. ISBN 978-0-295-98723-1.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Unknown Eastern Ukraine, The Ukrainian Week (14 March 2012)

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Magocsi 1996, p. 692.

- ↑ Magocsi 1996, pp. 692–693.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Magocsi 1996, p. 693.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Magocsi 1996, p. 706.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Magocsi 1996, p. 705.

- ↑ The Rise Of Russia And The Fall Of The Soviet Empire, John B. Dunlop, p. 140.

- ↑ Magocsi 1996, p. 713.

Bibliography

- Magocsi, Paul R. (1996). A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-0830-5.

- Adams, Arthur E. Bolsheviks in the Ukraine: The Second Campaign, 1918—1919 (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1963).

- Armstrong, John A. The Soviet Bureaucratic Elite: A Case Study of the Ukrainian Apparatus (New York: Praeger, 1959).

- Dmytryshyn, Basil. Moscow and the Ukraine, 1918—1953: A Study of Russian Bolshevik Nationality Policy (New York: Bookman Associates, 1956).

- Manning, Clarence A. Ukraine under the Soviets (New York: Bookman Associates, 1953).

- Sullivant, Robert S. Soviet Politics and the Ukraine, 1917—1957 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1962).

External links

- "Constitution of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic" (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. 1978. http://gska2.rada.gov.ua/site/const/istoriya/1978.html. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

[ ⚑ ] 50°27′N 30°30′E / 50.45°N 30.5°E