SIC-POVM

In the context of quantum mechanics and quantum information theory, symmetric, informationally complete, positive operator-valued measures (SIC-POVMs) are a particular type of generalized measurement (POVM). SIC-POVMs are particularly notable thanks to their defining features of (1) being informationally complete; (2)having the minimal number of outcomes compatible with informational completeness, and (3) being highly symmetric. In this context, informational completeness is the property of a POVM of allowing to fully reconstruct input states from measurement data.

The properties of SIC-POVMs make them an interesting candidate for a "standard quantum measurement", utilized in the study of foundational quantum mechanics, most notably in QBism[citation needed]. SIC-POVMs have several applications in the context of quantum state tomography[1] and quantum cryptography,[2] and a possible connection has been discovered with Hilbert's twelfth problem.[3]

Definition

| Unsolved problem in mathematics: Do SIC-POVMs exist in all dimensions? (more unsolved problems in mathematics)

|

A POVM over a

-dimensional Hilbert space

is a set of

positive-semidefinite operators

that sum to the identity:

If a POVM consists of at least operators which span the space of self-adjoint operators , it is said to be an informationally complete POVM (IC-POVM). IC-POVMs consisting of exactly elements are called minimal. A set of rank-1 projectors which have equal pairwise Hilbert–Schmidt inner products, defines a minimal IC-POVM with elements called a SIC-POVM.

Properties

Symmetry

Consider an arbitrary set of rank-1 projectors such that is a POVM, and thus . Asking the projectors to have equal pairwise inner products, for all , fixes the value of . To see this, observe that implies that . Thus, This property is what makes SIC-POVMs symmetric; with respect to the Hilbert–Schmidt inner product, any pair of elements is equivalent to any other pair.

Superoperator

In using the SIC-POVM elements, an interesting superoperator can be constructed, the likes of which map . This operator is most useful in considering the relation of SIC-POVMs with spherical t-designs. Consider the map

This operator acts on a SIC-POVM element in a way very similar to identity, in that

But since elements of a SIC-POVM can completely and uniquely determine any quantum state, this linear operator can be applied to the decomposition of any state, resulting in the ability to write the following:

- where

From here, the left inverse can be calculated[4] to be , and so with the knowledge that

- ,

an expression for a state can be created in terms of a quasi-probability distribution, as follows:

where is the Dirac notation for the density operator viewed in the Hilbert space . This shows that the appropriate quasi-probability distribution (termed as such because it may yield negative results) representation of the state is given by

Finding SIC sets

Simplest example

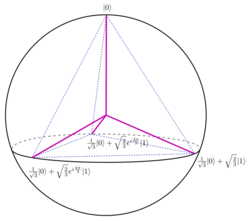

For the equations that define the SIC-POVM can be solved by hand, yielding the vectors

which form the vertices of a regular tetrahedron in the Bloch sphere. The projectors that define the SIC-POVM are given by , and the elements of the SIC-POVM are thus .

For higher dimensions this is not feasible, necessitating the use of a more sophisticated approach.

Group covariance

General group covariance

A SIC-POVM is said to be group covariant if there exists a group with a -dimensional unitary representation such that

The search for SIC-POVMs can be greatly simplified by exploiting the property of group covariance. Indeed, the problem is reduced to finding a normalized fiducial vector such that

- .

The SIC-POVM is then the set generated by the group action of on .

The case of Zd × Zd

So far, most SIC-POVM's have been found by considering group covariance under .[5] To construct the unitary representation, we map to , the group of unitary operators on d-dimensions. Several operators must first be introduced. Let be a basis for , then the phase operator is

- where is a root of unity

and the shift operator as

Combining these two operators yields the Weyl operator which generates the Heisenberg-Weyl group. This is a unitary operator since

It can be checked that the mapping is a projective unitary representation. It also satisfies all of the properties for group covariance,[6] and is useful for numerical calculation of SIC sets.

Zauner's conjecture

Given some of the useful properties of SIC-POVMs, it would be useful if it were positively known whether such sets could be constructed in a Hilbert space of arbitrary dimension. Originally proposed in the dissertation of Zauner,[7] a conjecture about the existence of a fiducial vector for arbitrary dimensions was hypothesized.

More specifically,

For every dimension there exists a SIC-POVM whose elements are the orbit of a positive rank-one operator under the Weyl–Heisenberg group . What is more, commutes with an element T of the Jacobi group . The action of T on modulo the center has order three.

Utilizing the notion of group covariance on , this can be restated as [8]

For any dimension , let be an orthonormal basis for , and define

Then such that the set is a SIC-POVM.

Partial results

The proof for the existence of SIC-POVMs for arbitrary dimensions remains an open question,[6] but is an ongoing field of research in the quantum information community.

Exact expressions for SIC sets have been found for Hilbert spaces of all dimensions from through inclusive, and in some higher dimensions as large as , for 115 values of in all.[lower-alpha 1] Furthermore, using the Heisenberg group covariance on , numerical solutions have been found for all integers up through , and in some larger dimensions up to .[lower-alpha 2]

Relation to spherical t-designs

A spherical t-design is a set of vectors on the d-dimensional generalized hypersphere, such that the average value of any -order polynomial over is equal to the average of over all normalized vectors . Defining as the t-fold tensor product of the Hilbert spaces, and

as the t-fold tensor product frame operator, it can be shown that[8] a set of normalized vectors with forms a spherical t-design if and only if

It then immediately follows that every SIC-POVM is a 2-design, since

which is precisely the necessary value that satisfies the above theorem.

Relation to MUBs

In a d-dimensional Hilbert space, two distinct bases are said to be mutually unbiased if

This seems similar in nature to the symmetric property of SIC-POVMs. Wootters points out that a complete set of unbiased bases yields a geometric structure known as a finite projective plane, while a SIC-POVM (in any dimension that is a prime power) yields a finite affine plane, a type of structure whose definition is identical to that of a finite projective plane with the roles of points and lines exchanged. In this sense, the problems of SIC-POVMs and of mutually unbiased bases are dual to one another.[17]

In dimension , the analogy can be taken further: a complete set of mutually unbiased bases can be directly constructed from a SIC-POVM.[18] The 9 vectors of the SIC-POVM, together with the 12 vectors of the mutually unbiased bases, form a set that can be used in a Kochen–Specker proof.[19] However, in 6-dimensional Hilbert space, a SIC-POVM is known, but no complete set of mutually unbiased bases has yet been discovered, and it is widely believed that no such set exists.[20][21]

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Caves, Carlton M.; Fuchs, Christopher A.; Schack, Rüdiger (September 2002). "Unknown quantum states: The quantum de Finetti representation" (in en). Journal of Mathematical Physics 43 (9): 4537–4559. doi:10.1063/1.1494475. ISSN 0022-2488. Bibcode: 2002JMP....43.4537C.

- ↑ Fuchs, C. A.; Sasaki, M. (2003). "Squeezing Quantum Information through a Classical Channel: Measuring the 'Quantumness' of a Set of Quantum States". Quant. Info. Comp. 3: 377–404. Bibcode: 2003quant.ph..2092F.

- ↑ Appleby, Marcus; Flammia, Steven; McConnell, Gary; Yard, Jon (2017-04-24). "SICs and Algebraic Number Theory" (in en). Foundations of Physics 47 (8): 1042–1059. doi:10.1007/s10701-017-0090-7. ISSN 0015-9018. Bibcode: 2017FoPh...47.1042A.

- ↑ C.M. Caves (1999); http://info.phys.unm.edu/~caves/reports/infopovm.pdf

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Fuchs, Christopher A.; Hoang, Michael C.; Stacey, Blake C. (2017-03-22). "The SIC Question: History and State of Play". Axioms 6 (4): 21. doi:10.3390/axioms6030021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Appleby, D. M. (2005). "SIC-POVMs and the Extended Clifford Group". Journal of Mathematical Physics 46 (5): 052107. doi:10.1063/1.1896384. Bibcode: 2005JMP....46e2107A.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 G. Zauner, Quantendesigns – Grundzüge einer nichtkommutativen Designtheorie. Dissertation, Universität Wien, 1999. http://www.gerhardzauner.at/documents/gz-quantendesigns.pdf

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Renes, Joseph M.; Blume-Kohout, Robin; Scott, A. J.; Caves, Carlton M. (2004). "Symmetric Informationally Complete Quantum Measurements". Journal of Mathematical Physics 45 (6): 2171. doi:10.1063/1.1737053. Bibcode: 2004JMP....45.2171R.

- ↑ A. Koldobsky and H. König, “Aspects of the Isometric Theory of Banach Spaces,” in Handbook of the Geometry of Banach Spaces, Vol. 1, edited by W. B. Johnson and J. Lindenstrauss, (North Holland, Dordrecht, 2001), pp. 899–939.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Scott, A. J.; Grassl, M. (2010). "SIC-POVMs: A new computer study". Journal of Mathematical Physics 51 (4): 042203. doi:10.1063/1.3374022. Bibcode: 2010JMP....51d2203S.

- ↑ TY Chien. ``Equiangular lines, projective symmetries and nice error frames. PhD thesis University of Auckland (2015); https://www.math.auckland.ac.nz/~waldron/Tuan/Thesis.pdf

- ↑ "Exact SIC fiducial vectors". http://www.physics.usyd.edu.au/~sflammia/SIC/.

- ↑ Appleby, Marcus; Chien, Tuan-Yow; Flammia, Steven; Waldron, Shayne (2018). "Constructing exact symmetric informationally complete measurements from numerical solutions". Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical 51 (16): 165302. doi:10.1088/1751-8121/aab4cd. Bibcode: 2018JPhA...51p5302A.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Stacey, Blake C. (2021). A First Course in the Sporadic SICs. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. pp. 6. ISBN 978-3-030-76104-2. OCLC 1253477267. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1253477267.

- ↑ Fuchs, Christopher A.; Stacey, Blake C. (2016-12-21). "QBism: Quantum Theory as a Hero's Handbook". arXiv:1612.07308 [quant-ph].

- ↑ Scott, A. J. (2017-03-11). "SICs: Extending the list of solutions". arXiv:1703.03993 [quant-ph].

- ↑ Wootters, William K. (2004). "Quantum measurements and finite geometry". arXiv:quant-ph/0406032.

- ↑ Stacey, Blake C. (2016). "SIC-POVMs and Compatibility among Quantum States". Mathematics 4 (2): 36. doi:10.3390/math4020036.

- ↑ Bengtsson, Ingemar; Blanchfield, Kate; Cabello, Adán (2012). "A Kochen–Specker inequality from a SIC". Physics Letters A 376 (4): 374–376. doi:10.1016/j.physleta.2011.12.011. Bibcode: 2012PhLA..376..374B.

- ↑ Grassl, Markus (2004). "On SIC-POVMs and MUBs in Dimension 6". arXiv:quant-ph/0406175.

- ↑ Bengtsson, Ingemar; Życzkowski, Karol (2017). Geometry of quantum states : an introduction to quantum entanglement (Second ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 313–354. ISBN 9781107026254. OCLC 967938939.

|