Social:Kharosthi

| Kharosthi 𐨑𐨪𐨆𐨮𐨿𐨛𐨁𐨌 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Abugida

|

| Languages | |

Time period | 4th century BCE – 3rd century CE |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems |

|

| Direction | Right-to-left |

| ISO 15924 | Khar, 305 |

Unicode alias | Kharoshthi |

| U+10A00–U+10A5F | |

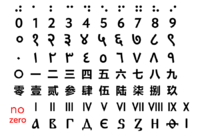

| Numeral systems |

|---|

|

| Hindu–Arabic numeral system |

| East Asian |

| Alphabetic |

| Former |

| Positional systems by base |

| Non-standard positional numeral systems |

| List of numeral systems |

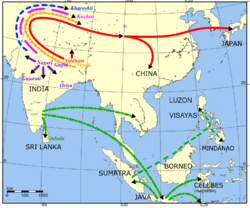

The Kharoṣṭhī script (Kharosthi: 𐨑𐨪𐨆𐨮𐨿𐨛𐨁𐨌, also spelled Kharoshthi), also known as the Gāndhārī script,[6] was an ancient Indo-Iranian script used by various peoples from the north-western outskirts of the Indian subcontinent (present-day Pakistan ) to Central Asia via Afghanistan.[1] An abugida, it was introduced at least by the middle of the 3rd century BCE, possibly during the 4th century BCE,[7] and remained in use until it died out in its homeland around the 3rd century CE.[1]

It was also in use in Bactria, the Kushan Empire, Sogdia, and along the Silk Road. There is some evidence it may have survived until the 7th century in Khotan and Niya, both cities in East Turkestan.

History

The name Kharosthi may derive from the Hebrew kharosheth, a Semitic word for writing,[8] or from Old Iranian *xšaθra-pištra, which means "royal writing".[9] The script was earlier also known as "Indo-Bactrian script", "Kabul script" and "Arian-Pali".[10][11]

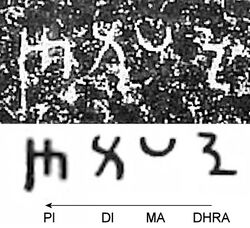

Scholars are not in agreement as to whether the Kharosthi script evolved gradually, or was the deliberate work of a single inventor. An analysis of the script forms shows a clear dependency on the Aramaic alphabet but with extensive modifications. Kharosthi seems to be derived from a form of Aramaic used in administrative work during the reign of Darius the Great, rather than the monumental cuneiform used for public inscriptions.[8] One theory suggests that the Aramaic script arrived with the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley in 500 BCE and evolved over the next 200+ years to reach its final form by the 3rd century BCE where it appears in some of the Edicts of Ashoka. However, no intermediate forms have yet been found to confirm this evolutionary model, and rock and coin inscriptions from the 3rd century BCE onward show a unified and standard form. An inscription in Aramaic dating back to the 4th century BCE was found in Sirkap, testifying to the presence of the Aramaic script in present-day Pakistan. According to Sir John Marshall, this seems to confirm that Kharoshthi was later developed from Aramaic.[12]

While the derived Brahmi scripts remained in use for centuries, Kharosthi seems to have been abandoned after the 2nd–3rd century AD. Because of the substantial differences between the Semitic-derived Kharosthi script and its successors, knowledge of Kharosthi may have declined rapidly once the script was supplanted by Brahmi-derived scripts, until its re-discovery by Western scholars in the 19th century.[8]

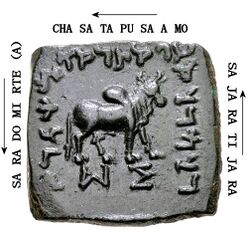

The Kharosthi script was deciphered separately almost concomitantly by James Prinsep (in 1835, published in the Journal of the Asiatic society of Bengal, India)[13] and by Carl Ludwig Grotefend (in 1836, published in Blätter für Münzkunde, Germany),[14] with Grotefend "evidently not aware" of Prinsep's article, followed by Christian Lassen (1838).[15] They all used the bilingual coins of the Indo-Greek Kingdom (obverse in Greek, reverse in Pali, using the Kharosthi script). This in turn led to the reading of the Edicts of Ashoka, some of which were written in the Kharosthi script (the Major Rock Edicts at Mansehra and Shahbazgarhi).[8]

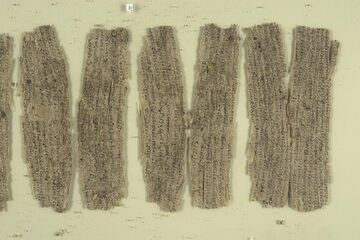

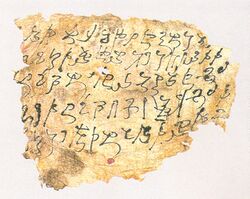

The study of the Kharosthi script was recently invigorated by the discovery of the Gandhāran Buddhist texts, a set of birch bark manuscripts written in Kharosthi, discovered near the Afghan city of Hadda just west of the Khyber Pass in Pakistan . The manuscripts were donated to the British Library in 1994. The entire set of British Library manuscripts are dated to the 1st century CE, although other collections from different institutions contain Kharosthi manuscripts from 1st century BCE to 3rd century CE,[16][17] making them the oldest Buddhist manuscripts yet discovered.

Characteristics

Kharosthi (𐨑𐨪𐨆𐨮𐨿𐨛𐨁𐨌, from right to left Kha-ro-ṣṭhī) is mostly written right to left (type A).

Each syllable includes the short /a/ sound by default[citation needed], with other vowels being indicated by diacritic marks. Recent epigraphic evidence[citation needed] has shown that the order of letters in the Kharosthi script follows what has become known as the Arapacana alphabet. As preserved in Sanskrit documents, the alphabet runs:[citation needed]

- a ra pa ca na la da ba ḍa ṣa va ta ya ṣṭa ka sa ma ga stha ja śva dha śa kha kṣa sta jñā rtha (or ha) bha cha sma hva tsa gha ṭha ṇa pha ska ysa śca ṭa ḍha

Some variations in both the number and order of syllables occur in extant texts.[citation needed]

Kharosthi includes only one standalone vowel character, which is used for initial vowels in words.[citation needed] Other initial vowels use the a character modified by diacritics. Using epigraphic evidence, Salomon has established that the vowel order is /a e i o u/, akin to Semitic scripts, rather than the usual vowel order for Indic scripts /a i u e o/. Also, there is no differentiation between long and short vowels in Kharosthi. Both are marked using the same vowel markers.

The alphabet was used in Gandharan Buddhism as a mnemonic for remembering a series of verses on the nature of phenomena. In Tantric Buddhism, the list was incorporated into ritual practices and later became enshrined in mantras.

Vowels

| Initial | Diacritic | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Text | Trans. | IPA | Image | Text | With 'k' | |||

| Unrounded | low central | 𐨀 | a | /ə/ | — | — | 𐨐 | ka | |

| high front | 𐨀𐨁 | i | /i/ | 𐨁 | 𐨐𐨁 | ki | |||

| Rounded | high back | 𐨀𐨂 | u | /u/ | 𐨂 | 𐨐𐨂 | ku | ||

| Syllabic vibrant | 𐨃 | 𐨐𐨃 | kr̥ | ||||||

| Mid | front unrounded | 𐨀𐨅 | e | /e/ | 𐨅 | 𐨐𐨅 | ke | ||

| back rounded | 𐨀𐨆 | o | /o/ | 𐨆 | 𐨐𐨆 | ko | |||

| Vowel | Position | Example | Applies to |

|---|---|---|---|

| -i | horizontal | 𐨀 + 𐨁 → 𐨀𐨁 | a, n, h |

| diagonal | 𐨐 + 𐨁 → 𐨐𐨁 | k, ḱ, kh, g, gh, c, ch, j, ñ, ṭ, ṭh, ṭ́h, ḍ, ḍh, ṇ, t, d, dh, b, bh, y, r, v, ṣ, s, z | |

| vertical | 𐨠 + 𐨁 → 𐨠𐨁 | th, p, ph, m, l, ś | |

| -u | attached | 𐨀 + 𐨂 → 𐨀𐨂 | a, k, ḱ, kh, g, gh, c, ch, j, ñ, ṭ, ṭh, ṭ́h, ḍ, ḍh, ṇ, t, th, d, dh, n, p, ph, b, bh, y, r, l, v, ś, ṣ, s, z |

| independent | 𐨱 + 𐨂 → 𐨱𐨂 | ṭ, h | |

| ligatured | 𐨨 + 𐨂 → 𐨨𐨂 | m | |

| -r̥ | attached | 𐨀 + 𐨃 → 𐨀𐨃 | a, k, ḱ, kh, g, gh, c, ch, j, t, d, dh, n, p, ph, b, bh, v, ś, s |

| independent | 𐨨 + 𐨃 → 𐨨𐨃 | m, h | |

| -e | horizontal | 𐨀 + 𐨅 → 𐨀𐨅 | a, n, h |

| diagonal | 𐨐 + 𐨅 → 𐨐𐨅 | k, ḱ, kh, g, gh, c, ch, j, ñ, ṭ, ṭh, ṭ́h, ḍ, ḍh, ṇ, t, dh, b, bh, y, r, v, ṣ, s, z | |

| vertical | 𐨠 + 𐨅 → 𐨠𐨅 | th, p, ph, l, ś | |

| ligatured | 𐨡 + 𐨅 → 𐨡𐨅 | d, m | |

| -o | diagonal | 𐨀 + 𐨆 → 𐨀𐨆 | a, k, ḱ, kh, g, gh, c, ch, j, ñ, ṭ, ṭh, ṭ́h, ḍ, ḍh, ṇ, t, th, d, dh, n, b, bh, m, r, l, v, ṣ, s, z, h |

| vertical | 𐨤 + 𐨆 → 𐨤𐨆 | p, ph, y, ś |

Consonants

| VOICELESS PLOSIVES | VOICED PLOSIVES | NASALS | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaspirated | Aspirated | Unaspirated | Aspirated | |||||||||||||||

| Image | Text | Trans. | IPA | Image | Text | Trans. | Image | Text | Trans. | IPA | Image | Text | Trans. | Image | Text | Trans. | IPA | |

| Velar | 𐨐 | k | /k/ | 19px | 𐨑 | kh | 19px | 𐨒 | g | /ɡ/ | 𐨓 | gh | ||||||

| Palatal | 𐨕 | c | /c/ | 19px | 𐨖 | ch | 18px | 𐨗 | j | /ɟ/ | 𐨙 | ñ | /ɲ/ | |||||

| Retroflex | 𐨚 | ṭ | /ʈ/ | 18px | 𐨛 | ṭh | 18px | 𐨜 | ḍ | /ɖ/ | 19px | 𐨝 | ḍh | 𐨞 | ṇ | /ɳ/ | ||

| Dental | 𐨟 | t | /t/ | 19px | 𐨠 | th | 19px | 𐨡 | d | /d/ | 19px | 𐨢 | dh | 𐨣 | n | /n/ | ||

| Labial | 𐨤 | p | /p/ | 19px | 𐨥 | ph | 19px | 𐨦 | b | /b/ | 19px | 𐨧 | bh | 𐨨 | m | /m/ | ||

There are two special modified forms of these consonants:[19]

| Image | Text | Trans. | Image | Text | Trans. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modified form | 𐨲 | ḱ | 𐨳 | ṭ́h | ||

| Original form | 𐨐 | k | 𐨛 | ṭh |

| Palatal | Retroflex | Dental | Labial | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Text | Trans. | IPA | Image | Text | Trans. | IPA | Image | Text | Trans. | IPA | Image | Text | Trans. | IPA | |

| Sonorants | 𐨩 | y | /j/ | 18px | 𐨪 | r | /r/ | 18px | 𐨫 | l | /l/ | 𐨬 | v | /ʋ/ | ||

| Sibilants | 𐨭 | ś | /ɕ/ | 17px | 𐨮 | ṣ | /ʂ/ | 𐨯 | s | /s/ | ||||||

| Other | ||||||||||||||||

| 𐨰 | z | ? | ||||||||||||||

| 𐨱 | h | /h/ | ||||||||||||||

Additional marks

Various additional marks are used to modify vowels and consonants:[19]

| Mark | Trans. | Example | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 𐨌 | ◌̄ | 𐨨 + 𐨌 → 𐨨𐨌 | The vowel length mark may be used with -a, -i, -u, and -r̥ to indicate the equivalent long vowel (-ā, -ī, -ū, and r̥̄ respectively). When used with -e it indicates the diphthong -ai. When used with -o it indicates the diphthong -au. |

| 𐨍 | ◌͚ | 𐨯 + 𐨍 → 𐨯𐨍 | The vowel modifier double ring below appears in some Central Asian documents with vowels -a and -u.[21] Its precise phonetic function is unknown. |

| 𐨎 | ṃ | 𐨀 + 𐨎 → 𐨀𐨎 | An anusvara indicates nasalization of the vowel or a nasal segment following the vowel. It can be used with -a, -i, -u, -r̥, -e, and -o. |

| 𐨏 | ḥ | 𐨐 + 𐨏 → 𐨐𐨏 | A visarga indicates the unvoiced syllable-final /h/. It can also be used as a vowel length marker. Visarga is used with -a, -i, -u, -r̥, -e, and -o. |

| 𐨸 | ◌̄ | 𐨗 + 𐨸 → 𐨗𐨸 | A bar above a consonant can be used to indicate various modified pronunciations depending on the consonant, such as nasalization or aspiration. It is used with k, ṣ, g, c, j, n, m, ś, ṣ, s, and h. |

| 𐨹 | ◌́ or ◌̱ | 𐨒 + 𐨹 → 𐨒𐨹 | The cauda changes how consonants are pronounced in various ways, particularly fricativization. It is used with g, j, ḍ, t, d, p, y, v, ś, and s. |

| 𐨺 | ◌̣ | 𐨨 + 𐨺 → 𐨨𐨺 | The precise phonetic function of the dot below is unknown. It is used with m and h. |

| 𐨿 | (n/a) | A virama is used to suppress the inherent vowel that otherwise occurs with every consonant letter. Its effect varies based on situation: | |

| 𐨢 + 𐨁 + 𐨐 + 𐨿 → 𐨢𐨁𐨐𐨿 | When not followed by a consonant the virama causes the preceding consonant to be written as a subscript to the left of the letter before that consonant. | ||

| 𐨐 + 𐨿 + 𐨮 → 𐨐𐨿𐨮 | When the virama is followed by another consonant, it will trigger a combined form consisting of two or more consonants. This may be a ligature, a special combining form, or a combining full form depending on the consonants involved. The result takes into account any other combining marks. | ||

| 𐨯 + 𐨿 + 𐨩 → 𐨯𐨿𐨩 | |||

| 𐨐 + 𐨿 + 𐨟 → 𐨐𐨿𐨟 |

Punctuation

Nine Kharosthi punctuation marks have been identified:[19]

| Sign | Description | Sign | Description | Sign | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𐩐 | dot | 𐩓 | crescent bar | 𐩖 | danda |

| 𐩑 | small circle | 𐩔 | mangalam | 𐩗 | double danda |

| 𐩒 | circle | 𐩕 | lotus | 𐩘 | lines |

Numerals

Kharosthi included a set of numerals that are reminiscent of Roman numerals.[citation needed] The system is based on an additive and a multiplicative principle, but does not have the subtractive feature used in the Roman numeral system.[22]

| Value | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 20 | 100 | 1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | 18px | 18px | 18px | 18px | 18px | 18px | ||

| Text | 𐩀 | 𐩁 | 𐩂 | 𐩃 | 𐩄 | 𐩅 | 𐩆 | 𐩇 |

The numerals, like the letters, are written from right to left. There is no zero and no separate signs for the digits 5–9. Numbers in Kharosthi use an additive system.

For example, the number 1996 would be written as 1000 4 4 1 100 20 20 20 20 10 4 2 (image: ![]() 18px18px18px18px18px18px18px18px18px18px

18px18px18px18px18px18px18px18px18px18px![]() , text: 𐩇𐩃𐩃𐩀𐩆𐩅𐩅𐩅𐩅𐩄𐩃𐩁).

, text: 𐩇𐩃𐩃𐩀𐩆𐩅𐩅𐩅𐩅𐩄𐩃𐩁).

Unicode

Kharosthi was added to the Unicode Standard in March, 2005 with the release of version 4.1.

The Unicode block for Kharosthi is U+10A00–U+10A5F:

Gallery

-

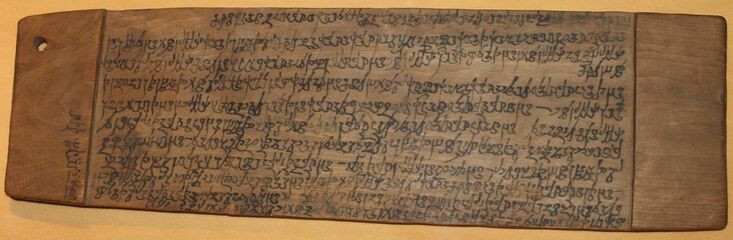

Kharosthi script on a wooden plate in the National Museum of India in New Delhi

-

Kharosthi script on a wooden plate in the National Museum of India in New Delhi

-

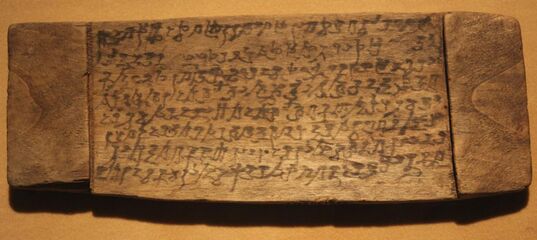

Kharosthi script on a wooden plate in the National Museum of India in New Delhi

-

Kharosthi script on wood from Niya, 3rd century CE

-

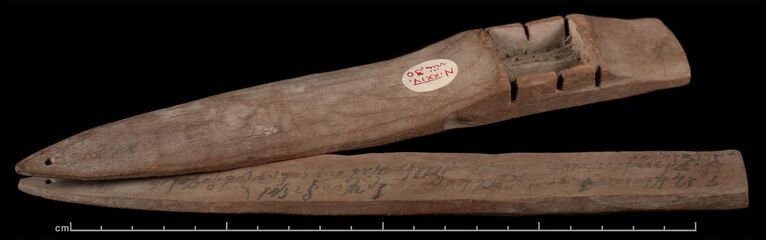

Double-wedged wooden tablet in Gandhari written in Kharosthi script, 2nd to 4th century CE

-

Wooden tablet inscribed with Kharosthi characters (2nd–3rd century CE). Excavated at the Niya ruins in Xinjiang, China. Collection of the Xinjiang Museum.

-

Wooden Kharosthi document found at Loulan, China by Aurel Stein

-

Silver bilingual tetradrachm of Menander I (155-130 BCE). Obverse: Greek legend, ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΣΩΤΗΡΟΣ ΜΕΝΑΝΔΡΟΥ (BASILEOS SOTEROS MENANDROU), literally, "Of Saviour King Menander". Reverse: Kharosthi legend: MAHARAJA TRATARASA MENADRASA "Saviour King Menander". Athena advancing right, with thunderbolt and shield. Taxila mint mark.

-

Coin of King Gurgamoya of Khotan (1st century CE). Obverse: Kharoshthi legend "Of the great king of kings, king of Khotan, Gurgamoya. Reverse: Chinese legend: "Twenty-four grain copper coin".

-

Coin of Menander II Dikaiou Obverse: Menander wearing a diadem. Greek legend: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΔΙΚΑΙΟΥ ΜΕΝΑΝΔΡΟΥ "King Menander the Just". Reverse: Winged figure bearing diadem and palm, with halo, probably Nike. The Kharoshthi legend reads MAHARAJASA DHARMIKASA MENADRASA "Great King, Menander, follower of the Dharma, Menander".

-

The Indo-Greek Hashtnagar Pedestal symbolizes bodhisattva and ancient Kharosthi script. Found near Rajar in Gandhara, Pakistan . Exhibited at the British Museum in London.

-

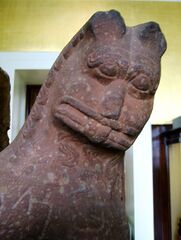

Mathura lion capital with addorsed lions and Prakrit inscriptions in Kharoshthi script

-

Fragments of stone well railings with a Buddhist inscription written in Kharoshthi script (late Han period to the Three Kingdoms era). Discovered at Luoyang, China in 1924.

-

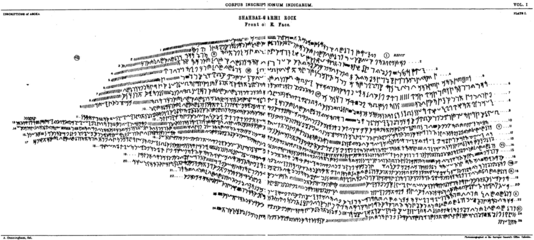

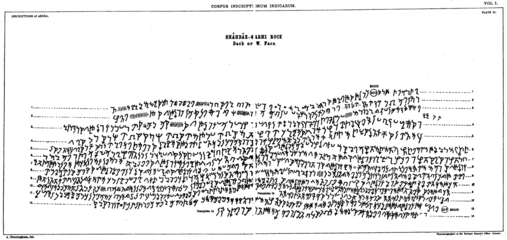

Portion of Emperor Ashoka's Rock Edicts at Shahbaz Garhi

-

Portion of Emperor Ashoka's Rock Edicts at Shahbaz Garhi

-

Document on Wooden Stick written in Kharoshthi script, 3rd-4th century CE.

See also

- Brahmi

- History of Afghanistan

- History of Pakistan

- Pre-Islamic scripts in Afghanistan

Further reading

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 R. D. Banerji (April 1920). "The Kharosthi Alphabet". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 52 (2): 193–219. doi:10.1017/S0035869X0014794X.

- ↑ Bühler, Georg (1895). "The Origin of the Kharoṣṭhī Alphabet". Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes 9: 44–66.

- ↑ "Kharosthi Script". https://www.worldhistory.org/Kharosthi_Script/.

- ↑ "Kharoshti: writing system". https://www.britannica.com/topic/Kharoshti.

- ↑ Salomon 1998, p. 20.

- ↑ Leitich, Keith A. (2017). "Kharoṣṭhī Script" (in en). Buddhism and Jainism. Encyclopedia of Indian Religions. Springer Netherlands. pp. 660–662. doi:10.1007/978-94-024-0852-2_238. ISBN 978-94-024-0851-5. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-94-024-0852-2_238.

- ↑ Salomon 1998, pp. 11–13.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Dias, Malini; Miriyagalla, Das (2007). "Brahmi Script in Relation to Mesopotamian Cuneiform". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka 53: 91–108.

- ↑ Bailey, H. W. (1972). "A Half-Century of Irano-Indian Studies". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 104 (2): 99–110. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00157466.

- ↑ "When these alphabets were first deciphered, scholars gave them different names such as 'Indian-Pali' for Brahmi and 'Arian-Pali' for Kharosthi, but these terms are no longer in use." in Upāsaka, Sī Esa; Mahāvihāra, Nava Nālandā (2002) (in en). History of palæography of Mauryan Brāhmī script. Nava Nālanda Mahāvihāra. p. 6. ISBN 9788188242047. https://books.google.com/books?id=P19jAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Kharosthi. Great Russian Encyclopedia.

- ↑ A Guide to Taxila, John Marshall, 1918

- ↑ (in English) Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol IV 1835. pp. 327–348. https://archive.org/details/JournalOfTheAsiaticSocietyOfBengalVolIv1835/page/n391/mode/2up.

- ↑ Grote, Hermann (1836) (in de). Blätter für Münzkunde. Hannoversche numismatische Zeitschrift. Hrsg. von H. Grote. Hahn. pp. 309–314. https://books.google.com/books?id=hVtfAAAAcAAJ.

- ↑ Salomon 1998, pp. 210–212.

- ↑ Richard, Salomon (2018). Buddhist Literature of Ancient Gandhara: An Introduction with Selected Translations. Simon and Schuster. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-61429-185-5. "…Subsequent studies have confirmed that these and other similar materials that were discovered in the following years date from between the first century BCE and the third century CE…"

- ↑ University of Washington. "The Early Buddhist Manuscripts Project": "...These manuscripts date from the first century BCE to the third century CE, and as such are the oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts as well as the oldest manuscripts from South Asia..." Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ↑ (in Sanskrit) Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch. 1925. pp. 56–57. https://archive.org/stream/InscriptionsOfAsoka.NewEditionByE.Hultzsch/HultzschCorpusAsokaSearchable#page/n197/mode/2up.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Glass, Andrew; Baums, Stefan; Salomon, Richard (2003-09-18). "L2/03-314R2: Proposal to Encode Kharoshthi in Plane 1 of ISO/IEC 10646". https://www.unicode.org/L2/L2003/03314-kharoshthi.pdf.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedWWS - ↑ Glass, Andrew; Baums, Stefan; Salomon, Richard (2003-09-29). "L2/02-364: Proposal to add one combining diacritic to the UCS". https://www.unicode.org/L2/L2002/02364-doublering.pdf.

- ↑ Graham Flegg, Numbers: Their History and Meaning, Courier Dover Publications, 2002, ISBN:978-0-486-42165-0, p. 67f.

Further reading

- Dani, Ahmad Hassan. Kharoshthi Primer, Lahore Museum Publication Series – 16, Lahore, 1979

- Falk, Harry. Schrift im alten Indien: Ein Forschungsbericht mit Anmerkungen, Gunter Narr Verlag, 1993 (in German)

- Fussman's, Gérard. Les premiers systèmes d'écriture en Inde, in Annuaire du Collège de France 1988–1989 (in French)

- Hinüber, Oscar von. Der Beginn der Schrift und frühe Schriftlichkeit in Indien, Franz Steiner Verlag, 1990 (in German)

- Nasim Khan, M.(1997). Ashokan Inscriptions: A Palaeographical Study. Atthariyyat (Archaeology), Vol. I, pp. 131–150. Peshawar

- Nasim Khan, M.(1999). Two Dated Kharoshthi Inscriptions from Gandhara. Journal of Asian Civilizations (Journal of Central Asia), Vol. XXII, No.1, July 1999: 99–103.

- Nasim Khan, M.(2000). An Inscribed Relic-Casket from Dir. The Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, Vol. V, No. 1, March 1997: 21–33. Peshawar

- Nasim Khan, M.(2000). Kharoshthi Inscription from Swabi – Gandhara. The Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, Vol. V, No. 2. September 1997: 49–52. Peshawar.

- Nasim Khan, M.(2004). Kharoshthi Manuscripts from Gandhara. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. Vol. XII, Nos. 1 & 2 (2004): 9–15. Peshawar

- Nasim Khan, M.(2009). Kharoshthi Manuscripts from Gandhara (2nd ed.. First published in 2008.

- Norman, Kenneth R. (1992). "The development of writing in India and its effect upon the Pāli canon". Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens 36: 239–249.

- Salomon, Richard (1990). "New Evidence for a Gāndhārī Origin of the Arapacana Syllabary". Journal of the American Oriental Society 110 (2): 255–273. doi:10.2307/604529.

- Salomon, Richard (1 April 1993). "An additional note on Aracapana". The Journal of the American Oriental Society 113 (2): 275–277. doi:10.2307/603034. Gale A14474853.

- Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

- Salomon, Richard (2006). "Kharoṣṭhī syllables used as location markers in Gāndhāran stūpa architecture". in Faccenna, Domenico. Architetti, Capomastri, Artigiani: L'organizzazione Dei Cantieri E Della Produzione Artistica Nell'Asia Ellenistica : Studi Offerti a Domenico Faccenna Nel Suo Ottantesimo Compleanno. Istituto italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente. pp. 181–224. ISBN 978-88-85320-36-9.

- Salomon, Richard (1995). "On the Origin of the Early Indian Scripts". Journal of the American Oriental Society 115 (2): 271–279. doi:10.2307/604670. ProQuest 217141859.

External links

- Gandhari.org Catalog and Corpus of all known Kharoṣṭhī (Gāndhārī) texts

- Indoskript 2.0, a paleographic database of Brahmi and Kharosthi

- A Preliminary Study of Kharoṣṭhī Manuscript Paleography by Andrew Glass, University of Washington (2000)

|