Social:Packaging and labeling

Packaging is the science, art and technology of enclosing or protecting products for distribution, storage, sale, and use. Packaging also refers to the process of designing, evaluating, and producing packages. Packaging can be described as a coordinated system of preparing goods for transport, warehousing, logistics, sale, and end use. Packaging contains, protects, preserves, transports, informs, and sells.[1] In many countries it is fully integrated into government, business, institutional, industrial, and personal use.

Package labeling (American English) or labelling (British English) is any written, electronic, or graphic communication on the package or on a separate but associated label.

History of packaging

Ancient era

The first packages used the natural materials available at the time: baskets of reeds, wineskins (bota bags), wooden boxes, pottery vases, ceramic amphorae, wooden barrels, woven bags, etc. Processed materials were used to form packages as they were developed: first glass and bronze vessels. The study of old packages is an essential aspect of archaeology.

The first usage of paper for packaging was sheets of treated mulberry bark used by the Chinese to wrap foods as early as the first or second century B.C.[2]

The usage of paper-like material in Europe was when the Romans used low grade and recycled papyrus for the packaging of incense.[3]

The earliest recorded use of paper for packaging dates back to 1035, when a Persian traveller visiting markets in Cairo, Arab Egypt, noted that vegetables, spices and hardware were wrapped in paper for the customers after they were sold.[3]

Modern era

Tinplate

The use of tinplate for packaging dates back to the 18th century. The manufacturing of tinplate was the monopoly of Bohemia for a long time; in 1667 Andrew Yarranton, an English engineer, and Ambrose Crowley brought the method to England where it was improved by ironmasters including Philip Foley.[4][5] By 1697, John Hanbury[6] had a rolling mill at Pontypool for making "Pontypoole Plates".[7][8] The method pioneered there of rolling iron plates by means of cylinders enabled more uniform black plates to be produced than was possible with the former practice of hammering.

Tinplate boxes first began to be sold from ports in the Bristol Channel in 1725. The tinplate was shipped from Newport, Monmouthshire.[9] By 1805, 80,000 boxes were made and 50,000 exported. Tobacconists in London began packaging snuff in metal-plated canisters from the 1760s onwards.

Canning

With the discovery of the importance of airtight containers for food preservation by French inventor Nicholas Appert, the tin canning process was patented by British merchant Peter Durand in 1810.[10] After receiving the patent, Durand did not himself follow up with canning food. He sold his patent in 1812 to two other Englishmen, Bryan Donkin and John Hall, who refined the process and product and set up the world's first commercial canning factory on Southwark Park Road, London. By 1813, they were producing the first canned goods for the Royal Navy.[11]

The progressive improvement in canning stimulated the 1855 invention of the can opener. Robert Yeates, a cutlery and surgical instrument maker of Trafalgar Place West, Hackney Road, Middlesex, UK, devised a claw-ended can opener with a hand-operated tool that haggled its way around the top of metal cans.[12] In 1858, another lever-type opener of a more complex shape was patented in the United States by Ezra Warner of Waterbury, Connecticut.

Paper-based packaging

Set-up boxes were first used in the 16th century and modern folding cartons date back to 1839. The first corrugated box was produced commercially in 1817 in England. Corrugated (also called pleated) paper received a British patent in 1856 and was used as a liner for tall hats. Scottish-born Robert Gair invented the pre-cut paperboard box in 1890—flat pieces manufactured in bulk that folded into boxes. Gair's invention came about as a result of an accident: as a Brooklyn printer and paper-bag maker during the 1870s, he was once printing an order of seed bags, and the metal ruler, commonly used to crease bags, shifted in position and cut them. Gair discovered that by cutting and creasing in one operation he could make prefabricated paperboard boxes.[13]

Commercial paper bags were first manufactured in Bristol, England , in 1844, and the American Francis Wolle patented a machine for automated bag-making in 1852.

20th century

Packaging advancements in the early 20th century included Bakelite closures on bottles, transparent cellophane overwraps and panels on cartons. These innovations increased processing efficiency and improved food safety. As additional materials such as aluminum and several types of plastic were developed, they were incorporated into packages to improve performance and functionality.[14]

In 1952, Michigan State University became the first university in the world to offer a degree in Packaging Engineering.[15]

In-plant recycling has long been typical for producing packaging materials. Post-consumer recycling of aluminum and paper-based products has been economical for many years: since the 1980s, post-consumer recycling has increased due to curbside recycling, consumer awareness, and regulatory pressure.

Many prominent innovations in the packaging industry were developed first for military use. Some military supplies are packaged in the same commercial packaging used for general industry. Other military packaging must transport materiel, supplies, foods, etc. under severe distribution and storage conditions. Packaging problems encountered in World War II led to Military Standard or "mil spec" regulations being applied to packaging, which was then designated "military specification packaging". As a prominent concept in the military, mil spec packaging officially came into being around 1941, due to operations in Iceland experiencing critical losses, ultimately attributed to bad packaging. In most cases, mil spec packaging solutions (such as barrier materials, field rations, antistatic bags, and various shipping crates) are similar to commercial grade packaging materials, but subject to more stringent performance and quality requirements.[16]

(As of 2003), the packaging sector accounted for about two percent of the gross national product in developed countries. About half of this market was related to food packaging.[17] In 2019 the global food packaging market size was estimated at USD 303.26 billion, exhibiting a CAGR of 5.2% over the forecast period. Growing demand for packaged food by consumers owing to quickening pace of life and changing eating habits is expected to have a major impact on the market.

The purposes of packaging and package labels

Packaging and package labeling have several objectives[18]

- Physical protection – The objects enclosed in the package may require protection from, among other things, mechanical shock, vibration, electrostatic discharge, compression, temperature,[19] etc.

- Barrier protection – A barrier to oxygen, water vapor, dust, etc., is often required. Permeation is a critical factor in design. Some packages contain desiccants or oxygen absorbers to help extend shelf life. Modified atmospheres[20] or controlled atmospheres are also maintained in some food packages. Keeping the contents clean, fresh, sterile[21] and safe for the duration of the intended shelf life is a primary function. A barrier is also implemented in cases where segregation of two materials prior to end use is required, as in the case of special paints, glues, medical fluids, etc.

- Containment or agglomeration – Small objects are typically grouped together in one package for reasons of storage and selling efficiency. For example, a single box of 1000 marbles requires less physical handling than 1000 single marbles. Liquids, powders, and granular materials need containment.

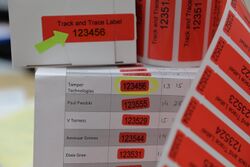

- Information transmission – Packages and labels communicate how to use, transport, recycle, or dispose of the package or product. With pharmaceuticals, food, medical, and chemical products, some types of information are required by government legislation. Some packages and labels also are used for track and trace purposes. Most items include their serial and lot numbers on the packaging, and in the case of food products, medicine, and some chemicals the packaging often contains an expiry/best-before date, usually in a shorthand form. Packages may indicate their construction material with a symbol.

- Marketing – Packaging and labels can be used by marketers to encourage potential buyers to purchase a product. Package graphic design and physical design have been important and constantly evolving phenomena for several decades. Marketing communications and graphic design are applied to the surface of the package and often to the point of sale display. Most packaging is designed to reflect the brand's message and identity on the one hand while highlighting the respective product concept on the other hand.

- Security – Packaging can play an important role in reducing the security risks of shipment. Packages can be made with improved tamper resistance to deter manipulation and they can also have tamper-evident[22] features indicating that tampering has taken place. Packages can be engineered to help reduce the risks of package pilferage or the theft and resale of products: Some package constructions are more resistant to pilferage than other types, and some have pilfer-indicating seals. Counterfeit consumer goods, unauthorized sales (diversion), material substitution and tampering can all be minimized or prevented with such anti-counterfeiting technologies. Packages may include authentication seals and use security printing to help indicate that the package and contents are not counterfeit. Packages also can include anti-theft devices such as dye-packs, RFID tags, or electronic article surveillance[23] tags that can be activated or detected by devices at exit points and require specialized tools to deactivate. Using packaging in this way is a means of retail loss prevention.

- Convenience – Packages can have features that add convenience in distribution, handling, stacking, display, sale, opening, reclosing, using, dispensing, reusing, recycling, and ease of disposal

- Portion control – Single serving or single dosage packaging has a precise amount of contents to control usage. Bulk commodities (such as salt) can be divided into packages that are a more suitable size for individual households. It also aids the control of inventory: selling sealed one-liter bottles of milk, rather than having people bring their own bottles to fill themselves.

- Branding/Positioning – Packaging and labels are increasingly used to go beyond marketing to brand positioning, with the materials used and design chosen key to the storytelling element of brand development. Due to the increasingly fragmented media landscape in the digital age this aspect of packaging is of growing importance.

Packaging types

Packaging may be of several different types. For example, a transport package or distribution package can be the shipping container used to ship, store, and handle the product or inner packages. Some identify a consumer package as one which is directed toward a consumer or household.

Packaging may be described in relation to the type of product being packaged: medical device packaging, bulk chemical packaging, over-the-counter drug packaging, retail food packaging, military materiel packaging, pharmaceutical packaging, etc.

It is sometimes convenient to categorize packages by layer or function: primary, secondary, etc.

- Primary packaging is the material that first envelops the product and holds it. This usually is the smallest unit of distribution or use and is the package which is in direct contact with the contents.

- Secondary packaging is outside the primary packaging, and may be used to prevent pilferage or to group primary packages together.

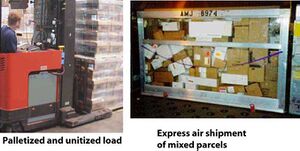

- Tertiary or transit packaging is used for bulk handling, warehouse storage and transport shipping. The most common form is a palletized unit load that packs tightly into containers.

These broad categories can be somewhat arbitrary. For example, depending on the use, a shrink wrap can be primary packaging when applied directly to the product, secondary packaging when used to combine smaller packages, or tertiary packaging when used to facilitate some types of distribution, such as to affix a number of cartons on a pallet.

Packaging can also have categories based on the package form. For example, thermoform packaging and flexible packaging describe broad usage areas.

Labels and symbols used on packages

Many types of symbols for package labeling are nationally and internationally standardized. For consumer packaging, symbols exist for product certifications (such as the FCC and TÜV marks), trademarks, proof of purchase, etc. Some requirements and symbols exist to communicate aspects of consumer rights and safety, for example the CE marking or the estimated sign that notes conformance to EU weights and measures accuracy regulations. Examples of environmental and recycling symbols include the recycling symbol, the recycling code (which could be a resin identification code), and the "Green Dot". Food packaging may show food contact material symbols. In the European Union, products of animal origin which are intended to be consumed by humans have to carry standard, oval-shaped EC identification and health marks for food safety and quality insurance reasons.

Bar codes, Universal Product Codes, and RFID labels are common to allow automated information management in logistics and retailing. Country-of-origin labeling is often used. Some products might use QR codes or similar matrix barcodes. Packaging may have visible registration marks and other printing calibration and troubleshooting cues.

The labelling of medical devices includes many symbols, many of them covered by international standards, foremost ISO 15223-1.

Consumer package contents

Several aspects of consumer package labeling are subject to regulation. One of the most important is to accurately state the quantity (weight, volume, count) of the package contents. Consumers expect that the label accurately reflects the actual contents. Manufacturers and packagers must have effective quality assurance procedures and accurate equipment; even so, there is inherent variability in all processes.

Regulations attempt to handle both sides of this. In the USA, the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act provides requirements for many types of products. Also, NIST has Handbook 133, Checking the Net Contents of Packaged Goods.[24] This is a procedural guide for compliance testing of net contents and is referenced by several other regulatory agencies.[25]

Other regions and countries have their own regulatory requirements. For example, the UK has its Weights and Measures (Packaged Goods) Regulations[26] as well as several other regulations. In the EEA, products with hazardous formulas need to have a UFI.

Shipping container labeling

Technologies related to shipping containers are identification codes, bar codes, and electronic data interchange (EDI). These three core technologies serve to enable the business functions in the process of shipping containers throughout the distribution channel. Each has an essential function: identification codes either relate product information or serve as keys to other data, bar codes allow for the automated input of identification codes and other data, and EDI moves data between trading partners within the distribution channel.

Elements of these core technologies include UPC and EAN item identification codes, the SCC-14 (UPC shipping container code), the SSCC-18 (Serial Shipping Container Codes), Interleaved 2-of-5 and UCC/EAN-128 (newly designated GS1-128) bar code symbologies, and ANSI ASC X12 and UN/EDIFACT EDI standards.

Small parcel carriers often have their own formats. For example, United Parcel Service has a MaxiCode 2-D code for parcel tracking.

RFID labels for shipping containers are also increasingly used. A Wal-Mart division, Sam's Club, has also moved in this direction and is putting pressure on its suppliers to comply.[27]

Shipments of hazardous materials or dangerous goods have special information and symbols (labels, placards, etc.) as required by UN, country, and specific carrier requirements. On transport packages, standardized symbols are also used to communicate handling needs. Some are defined in the ASTM D5445 "Standard Practice for Pictorial Markings for Handling of Goods" and ISO 780 "Pictorial marking for handling of goods".

-

Flammable liquid

-

Explosives

-

This way up

-

Fragile material

-

Keep away from water

Package development considerations

Package design and development are often thought of as an integral part of the new product development process. Alternatively, the development of a package (or component) can be a separate process but must be linked closely with the product to be packaged. Package design starts with the identification of all the requirements: structural design, marketing, shelf life, quality assurance, logistics, legal, regulatory, graphic design, end-use, environmental, etc. The design criteria, performance (specified by package testing), completion time targets, resources, and cost constraints need to be established and agreed upon. Package design processes often employ rapid prototyping, computer-aided design, computer-aided manufacturing and document automation.

An example of how package design is affected by other factors is its relationship to logistics. When the distribution system includes individual shipments by a small parcel carrier, the sorting, handling, and mixed stacking make severe demands on the strength and protective ability of the transport package. If the logistics system consists of uniform palletized unit loads, the structural design of the package can be designed to meet those specific needs, such as vertical stacking for a longer time frame. A package designed for one mode of shipment may not be suited to another.

With some types of products, the design process involves detailed regulatory requirements for the packaging. For example, any package components that may contact foods are designated food contact materials.[28] Toxicologists and food scientists need to verify that such packaging materials are allowed by applicable regulations. Packaging engineers need to verify that the completed package will keep the product safe for its intended shelf life with normal usage. Packaging processes, labeling, distribution, and sale need to be validated to assure that they comply with regulations that have the well being of the consumer in mind.

Sometimes the objectives of package development seem contradictory. For example, regulations for an over-the-counter drug might require the package to be tamper-evident and child resistant:[29] These intentionally make the package difficult to open.[30] The intended consumer, however, might be disabled or elderly and unable to readily open the package. Meeting all goals is a challenge.

Package design may take place within a company or with various degrees of external packaging engineering: independent contractors, consultants, vendor evaluations, independent laboratories, contract packagers, total outsourcing, etc. Some sort of formal project planning and project management methodology is required for all but the simplest package design and development programs. An effective quality management system and Verification and Validation protocols are mandatory for some types of packaging and recommended for all.

Environmental considerations

Package development involves considerations of sustainability, environmental responsibility, and applicable environmental and recycling regulations. It may involve a life cycle assessment[31][32] which considers the material and energy inputs and outputs to the package, the packaged product (contents), the packaging process, the logistics system,[33] waste management, etc. It is necessary to know the relevant regulatory requirements for point of manufacture, sale, and use.

The traditional “three R’s” of reduce, reuse, and recycle are part of a waste hierarchy which may be considered in product and package development.

- Prevention – Waste prevention is a primary goal. Packaging should be used only where needed. Proper packaging can also help prevent waste. Packaging plays an important part in preventing loss or damage to the packaged product (contents). Usually, the energy content and material usage of the product being packaged are much greater than that of the package. A vital function of the package is to protect the product for its intended use: if the product is damaged or degraded, its entire energy and material content may be lost.

- Minimization (also "source reduction") – Eliminate overpackaging. The mass and volume of packaging (per unit of contents) can be measured and used as criteria for minimizing the package in the design process. Usually “reduced” packaging also helps minimize costs. Packaging engineers continue to work toward reduced packaging.[34]

- Reuse – Reusable packaging is encouraged.[35] Returnable packaging has long been useful (and economically viable) for closed-loop logistics systems. Inspection, cleaning, repair, and recouperage are often needed. Some manufacturers re-use the packaging of the incoming parts for a product, either as packaging for the outgoing product[36] or as part of the product itself.[37]

- Recycling – Recycling is the reprocessing of materials (pre- and post-consumer) into new products. Emphasis is focused on recycling the largest primary components of a package: steel, aluminum, papers, plastics, etc. Small components can be chosen which are not difficult to separate and do not contaminate recycling operations. Packages can sometimes be designed to separate components to better facilitate recycling.

- Energy recovery – Waste-to-energy and refuse-derived fuel in approved facilities make use of the heat available from incinerating the packaging components.

- Disposal – Incineration, and placement in a sanitary landfill are undertaken for some materials. Certain US states regulate packages for toxic contents, which have the potential to contaminate emissions and ash from incineration and leachate from landfill. Packages should not be littered.

Development of sustainable packaging is an area of considerable interest to standards organizations, governments, consumers, packagers, and retailers.

Sustainability is the fastest-growing driver for packaging development, particularly for packaging manufacturers that work with the world's leading brands, as their CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) targets often exceed those of the EU Directive.

Packaging machinery

Choosing packaging machinery includes an assessment of technical capabilities, labor requirements, worker safety, maintainability, serviceability, reliability, ability to integrate into the packaging line, capital cost, floorspace, flexibility (change-over, materials, multiple products, etc.), energy requirements, quality of outgoing packages, qualifications (for food, pharmaceuticals, etc.), throughput, efficiency, productivity, ergonomics, return on investment, etc.

Packaging machinery can be:

- purchased as standard, off-the-shelf equipment

- purchased custom-made or custom-tailored to specific operations

- manufactured or modified by in-house engineers and maintenance staff

Efforts at packaging line automation increasingly use programmable logic controllers and robotics.

Packaging machines may be of the following general types:

- Accumulating and collating machines

- Blister packs, skin packs and vacuum packaging machines

- Bottle caps equipment, over-capping, lidding, closing, seaming and sealing machines

- Box, case, tray, and carrier forming, packing, unpacking, closing, and sealing machines

- Cartoning machines

- Cleaning, sterilizing, cooling and drying machines

- Coding, printing, marking, stamping, and imprinting machines

- Converting machines

- Conveyor belts, accumulating and related machines

- Feeding, orienting, placing and related machines

- Filling machines: handling dry, powdered, solid, liquid, gas, or viscous products

- Inspecting: visual, sound, metal detecting, etc.

- Label dispenser

- Orienting, unscrambling machines

- Package filling and closing machines

- Palletizing, depalletizing, unit load assembly

- Product identification: labeling, marking, etc.

- Sealing machines: heat sealer or glue units

- Slitting machines

- Weighing machines: check weigher, multihead weigher

- Wrapping machines: stretch wrapping, shrink wrap, banding

- Form, fill and seal machines

- Other specialty machinery: slitters, perforating, laser cutters, parts attachment, etc.

-

Bakery goods shrinkwrapped by shrink film, heat sealer and heat tunnel on roller conveyor

-

High speed conveyor with stationary bar code scanner for sorting

-

Label printer applicator applying a label to adjacent panels of a corrugated box.

-

Robots used to palletize bread

-

Automatic stretch wrapping machine

-

A semi-automatic rotary arm stretch wrapper

-

Equipment for thermoforming packages at NASA

-

Automated labeling line for wine bottles

-

Shrink film wrap being applied on PET bottles

-

Pharmaceutical packaging line

-

Filling machinery for bag-in-box

See also

- Brazilian packaging market

- Document automation

- In-mould labelling

- Packing problems

- Package cushioning

- Polypropylene raffia

- Resealable packaging

- Gift wrapping

- Zero-waste lifestyle

References

- ↑ Soroka (2002) Fundamentals of Packaging Technology, Institute of Packaging Professionals ISBN:1-930268-25-4

- ↑ Paula, Hook (11 May 2017). "A History of Packaging". Ohio State University. https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/cdfs-133.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Diana Twede (2005). "The Origins of Paper Based Packaging". Conference on Historical Analysis & Research in Marketing Proceedings 12: 288–300 [289]. http://faculty.quinnipiac.edu/charm/CHARM%20proceedings/CHARM%20article%20archive%20pdf%20format/Volume%2012%202005/288%20twede.pdf. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ↑ Brown, P.J. (1988), "Andrew Yarranton and the British tinplate industry", Historical Metallurgy 22 (1): 42–48

- ↑ King, P.W. (1988), "Wolverley Lower Mill and the beginnings of the tinplate industry", Historical Metallurgy 22 (2): 104–113

- ↑ King 1988, p. 109

- ↑ H.R. Schubert, History of the British iron and steel industry ... to 1775, 429.

- ↑ Minchinton, W.W. (1957), The British tinplate industry: a history, Clarendon Press, Oxford, p. 10

- ↑ Data extracted from D.P. Hussey et al., Gloucester Port Books Database (CD-ROM, University of Wolverhampton 1995).

- ↑ Geoghegan, Tom (April 21, 2013). "BBC News - The story of how the tin can nearly wasn't". Bbc.co.uk. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-21689069.

- ↑ William H. Chaloner (1963). People and Industries. Routledge. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-7146-1284-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=eAA5M2eIWqwC.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Kitchen History. Taylor & Francis Group. September 27, 2004. ISBN 978-1-57958-380-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=D7IhN7lempUC.

- ↑ Diana Twede; Susan E.M. Selke (2005). Cartons, crates and corrugated board: handbook of paper and wood packaging technology. DEStech Publications. pp. 41–42, 55–56. ISBN 978-1-932078-42-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=kc0MSzFvrH8C.

- ↑ Brody, A. L; Marsh, K. S (1997). Encyclopedia of Packaging Technology. ISBN 978-0-471-06397-1.

- ↑ "Michigan State School of Packaging". Michigan State University. http://packaging.msu.edu.

- ↑ Maloney, J.C. (July 2003). "The History and Significance of Military Packaging". Defence Packaging Policy Group. Defence Logistics Agency. http://www.dla.mil/Portals/104/Documents/LandAndMaritime/V/VS/Packaging/LM_pkghistory_151007.pdf.

- ↑ Y. Schneider; C. Kluge; U. Weiß; H. Rohm (2010). "Packaging Materials and Equipment". in Barry A. Law, A.Y. Tamime. Technology of Cheesemaking: Second Edition. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 413. ISBN 978-1-4051-8298-0. https://archive.org/details/technologycheese00lawb.

- ↑ Bix, L; Rifon; Lockhart; de la Fuente (2003). "The Packaging Matrix: Linking Package Design Criteria to the Marketing Mix". IDS Packaging. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282313342. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ Choi, Seung-Jin; Burgess (2007). "Practical mathematical model to predict the performance of insulating packages". Packaging Technology and Science 20 (6): 369–380. doi:10.1002/pts.762.

- ↑ Lee, Ki-Eun; Kim; An; Lyu; Lee (1998). "Effectiveness of modified atmosphere packaging in preserving a prepared ready-to-eat food". Packaging Technology and Science 21 (7): 417. doi:10.1002/pts.821.

- ↑ Severin, J (2007). "New Methodology for Whole-Package Microbial Challenge Testing for Medical Device Trays". Journal of Testing and Evaluation 35 (4): 100869. doi:10.1520/JTE100869.

- ↑ Johnston, R.G. (1997). "Effective Vulnerability Assessment of Tamper-Indicating Seals". Journal of Testing and Evaluation 25 (4): 451. doi:10.1520/JTE11883J. http://library.lanl.gov/la-pubs/00418792.pdf.

- ↑ How Anti-shoplifting Devices Work”, HowStuffWorks.com

- ↑ "Checking the Net Contents of Packaged Goods, Handbook 133 - 2020", Nist (US National Institute of Science and Technology), 2020, https://www.nist.gov/pml/weights-and-measures/handbook-133-2020-current-version, retrieved 8 April 2020

- ↑ Hines, A (February 18, 2019). "WEIGHING YOUR OPTIONS WITH NIST HANDBOOK 133". Food Safety Net Services News. https://www.businesscompanion.info/en/quick-guides/weights-and-measures/packaged-goods-average-quantity. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ↑ The Weights and Measures (Packaged Goods) Regulations 2006, UK Statutory Instruments, 2006 No. 659, 2006, http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2006/659/contents/made, retrieved 8 April 2020

- ↑ Bacheldor, Beth (January 11, 2008). "Sam's Club Tells Suppliers to Tag or Pay". http://www.rfidjournal.com/article/articleview/3845/1/1/.

- ↑ Sotomayor, Rene E.; Arvidson, Kirk; Mayer, Julie; McDougal, Andrew; Sheu, Chingju (2007). "Regulatory Report, Assessing the Safety of Food Contact Substances". Food Safety. https://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodIngredientsPackaging/FoodContactSubstancesFCS/ucm064166.htm#authors.

- ↑ Rodgers, G.B. (1996). "The safety effects of child-resistant packaging for oral prescription drugs. Two decades of experience". JAMA 275 (21): 1661–65. doi:10.1001/jama.275.21.1661. PMID 8637140.

- ↑ Yoxall, A.; Janson, R.; Bradbury, S.R.; Langley, J.; Wearn, J.; Hayes, S. (2006). "Openability: producing design limits for consumer packaging". Packaging Technology and Science 16 (4): 183–243. doi:10.1002/pts.725.

- ↑ Zabaniotou, A; Kassidi (2003). "Life cycle assessment applied to egg packaging made from polystyrene and recycled paper". Journal of Cleaner Production 11 (5): 549–559. doi:10.1016/S0959-6526(02)00076-8.

- ↑ Franklin (April 2004). "Life Cycle Inventory of Packaging Options for Shipment of Retail Mail-Order Soft Goods". http://www.deq.state.or.us/lq/pubs/docs/sw/packaging/LifeCycleInventory.pdf.

- ↑ "SmartWay Transport Partnerships". US Environmental Protection Agency. http://www.epa.gov/smartway/transport/documents/faqs/partnership_overview.pdf.

- ↑ DeRusha, Jason (July 16, 2007). "The Incredible Shrinking Package". WCCO. http://wcco.com/topstories/local_story_197233456.html.

- ↑ Use Reusables: Fundamentals of Reusable Transport Packaging, US Environmental Protection Agency, 2012, http://www.epa.gov/wastes/conserve/smm/web-academy/2012/pdfs/smm812_Lehrer.pdf, retrieved June 30, 2014

- ↑ "HP DeskJet 1200C Printer Architecture". (PDF). Retrieved on June 27, 2012.

- ↑ "Footprints In The Sand" . Newsroom-magazine.com. Retrieved on June 27, 2012.

- ↑ Wood, Marcia (April 2002). "Leftover Straw Gets New Life". Agricultural Research. http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/AR/archive/apr02/straw0402.htm.

General references

- Yam, K.L., "Encyclopedia of Packaging Technology", John Wiley & Sons, 2009, ISBN:978-0-470-08704-6

- Soroka, W, Illustrated Glossary of Packaging Terminology Institute of Packaging Professionals,

Further reading

- Calver, G., What Is Packaging Design, Rotovision. 2004, ISBN:2-88046-618-0.

- Dean, D.A., 'Pharmaceutical Packaging Technology", 2000, ISBN:0-7484-0440-6

- Meisner, "Transport Packaging", Third Edition, IoPP, 2016

- Morris, S.A., "Food and Package Engineering", 2011, ISBN:978-0-8138-1479-7

- Pilchik, R., "Validating Medical Packaging" 2002, ISBN:1-56676-807-1

- Robertson, G.L., "Food Packaging: Principles and Practice", 3rd edition, 2013, ISBN:978-1-4398-6241-4

- Selke, S., "Plastics Packaging", 2004, ISBN:1-56990-372-7

- Tweede, Selke, Cartons, Crates And Corrugated Board: Handbook of Paper And Wood Packaging Technology, Destech Pub ,2014, 2nd edition,

External links

![Equipment used for making molded pulp components and molding packaging from straw[38]](/wiki/images/thumb/2/27/Molding_packaging_from_straw%2C_k9837-1.jpg/276px-Molding_packaging_from_straw%2C_k9837-1.jpg)