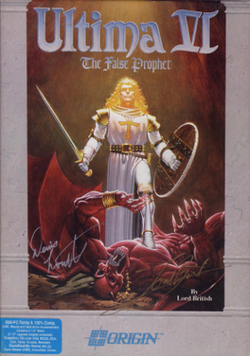

Software:Ultima VI: The False Prophet

| Ultima VI: The False Prophet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Origin Systems |

| Publisher(s) | Origin Systems |

| Producer(s) | Richard Garriott Warren Spector |

| Designer(s) | Richard Garriott |

| Series | Ultima |

| Platform(s) | MS-DOS, Amiga, Atari ST, Commodore 64, FM Towns, PC-98, Super NES, X68000 |

| Release | April 1990: MS-DOS[1] 1991–1992: ports |

| Genre(s) | Role-playing |

| Mode(s) | Single player |

Ultima VI: The False Prophet, released by Origin Systems in 1990, is the sixth part in the role-playing video game series of Ultima. It is the third and final game in the "Age of Enlightenment" trilogy. Ultima VI sees the player return to Britannia, at war with a race of gargoyles from another land, struggling to stop a prophecy from ending their race. The player must help defend Britannia against these gargoyles, and ultimately discover the secrets about both lands and its peoples.

Ultima VI continues to advance the technology of the Ultima series. The game world is larger, with a 1024x1024 tile map seamlessly connected and to scale. World interactivity is further increased with object manipulation, movement, and crafting. Graphics and sound are likewise advanced with the use of new sound card technology and VGA graphics cards, and the user interface is streamlined with the use of point-and-click icons.

Ultima VI was followed by Software:Ultima VII: The Black Gate in 1992.

Plot

Some years after Lord British has returned to power, the Avatar is captured and tied on a sacrificial altar, about to be sacrificed by red demon-like creatures, the gargoyles. Three of the Avatar's companions, Shamino, Dupre and Iolo, suddenly appear, save the Avatar and collect the sacred text the gargoyle priest was holding.

The Avatar's party flees through a moongate to Castle Britannia, and three of the gargoyles follow. The game begins with the player fighting the gargoyles in Lord British's throne room. After the battle, the Avatar learns that the shrines of Virtue were captured by the gargoyles and he embarks on a quest to rescue Britannia from the invaders.

It is only later in the game that the Avatar learns that the whole situation looks rather different from the point of view of the gargoyles – indeed, they even have their own system of virtues.[2] The quest for victory over the gargoyles now turns into a quest for peace with them.

Gameplay

This game ended the use of multiple scales; in earlier games a town, castle, or dungeon would be represented as a single symbol on the world map, which then expanded into a full sub-map when entering the structure. In Ultima VI, the whole game uses a single scale, with towns and other places seamlessly integrated into the main map; dungeons are now also viewed from the same perspective as the rest of the game, rather than the first-person perspective used by Ultima I-V. The game retained the basic tile system and screen layout of the three preceding games, but utilized a much more colourful and detailed oblique map view and displayed NPC portraits during conversations. These changes took full advantage of the recently released VGA graphics cards for PCs.

Development

The development of the Ultima series originated on the Apple II and every game thus far had been developed primarily on that platform, but by 1990 the market for 8-bit computers in the US had nearly evaporated, so there was no Apple II version for the first time. In any case, the games were starting to outgrow the capabilities of 8-bit hardware. Origin reportedly attempted an Apple II port of Ultima VI, but gave up after deciding it was impossible. A port for the more capable 16-bit Apple IIGS had been planned, and rumored to have been started, but was never released (despite mentions of the machine on the box packaging and manual). The game was ported to the Commodore 64, although not without trimming considerable elements including aesthetics (no portraits), but also gameplay (no horses, no working gems, reduced NPC dialogs, simplified quests, etc.).[3]

Some major changes were made that distinguished Ultima VI from earlier Ultima games. Several of these changes were influenced by Origin's 1988 action role-playing game, Times of Lore, created by Chris Roberts,[4][5] and FTL Games's 1987 RPG Dungeon Master.[6] One such change was the world design,[5] where no longer would towns and castles be represented by icons on the overworld map, but where everything in the game world is represented on the same 1024x1024 tile map, except for dungeons and smaller outdoor maps. The caverns and dungeons beneath the land were also no longer represented in first-person view, but changed to an overhead, oblique isometric view, like the rest of the game.[4][5] Another such change was the incorporation of some real-time elements.[5] Richard Garriott also based the game's new icon-based point and click interface on Times of Lore, streamlining the commands into ten icons.[4] Garriott expressed annoyance at not having thought of it sooner, realizing that "it was clearly the way to have gone" for earlier games.[7]

The software routines that governed every element of movement and combat was developed by 25 year-old Boston programmer Herman Miller, who previously wrote the IBM conversions of Ultima V and Times of Lore. The conversation system, the means by which the player talks with characters, was developed by 26 year-old Chinese programmer Cheryl Chen, who developed her own programming language for the game called UCS (Ultima VI conversation system).[4] Conversations with townspeople were no longer restricted in terms of length, compared to the limitations of earlier Ultima games.[4]

It was one of the first major PC games directly targeted to PC systems equipped with VGA graphics and a mouse, when the big gaming computer was still the Amiga. The game supported sound cards for music as well, which were not yet common when it was released. Other sound effects, such as the clashing of swords, magical zaps, or explosions, were still played through the PC speaker. The Amiga version was itself ported from the PC and due to a lack of reprogramming it was very slow and generally considered unplayable without accelerator card on a first- or second-generation Amiga.

A port of the game for Fujitsu's FM Towns platform was made primarily for the Japanese market.[8] This CD-ROM-based version included full speech in both English and Japanese. Remarkably, in this particular version voice acting was recorded at Origin under the direction of Martin Galway, mostly by the people the characters were based on (with Richard Garriott as Lord British, Greg Dykes as Dupre, Chuck Buche as Chuckles, etc.), though not all personnel could be reached at the time of recording, so some substitutes were used.

The game came with a cloth map of Britannia and a Moonstone made from a black colored bit of glass. Slightly improved versions of the Ultima VI engine were also used for the Worlds of Ultima spin-off series.

Origin produced a deluxe edition of Ultima VI for sale by mail order at the same $69.95 price as the retail version. Lord British autographed the copies, which contained an audio interview with him, game hints, and higher-quality moonstone.[9]

The DOS version of Ultima VI may have sound and speed problems when running on modern computers and operating systems. However, it can run reliably in a DOSBox environment. Several open-source remake projects exist; Nuvie [10] and xU4 aim to recreate the Ultima VI engine in a manner similar to the goals of Exult.[11]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

In 1990, the game had sold under 100,000 copies in the United States.[18]

Scorpia of Computer Gaming World in 1990 stated that she "had some profound, mixed feelings about" Ultima VI because of the changes to the user interface, graphics, and gameplay. The change to a single scale for the world, for example, greatly increased travel and exploration time; long quests had small rewards; and performance became sluggish with many characters on screen. She liked, however, the "solid story" that elegantly concluded the second trilogy, lack of pointless outdoor encounters, and improved NPC dialogues, and concluded that Ultima VI "is a very good game".[19] In 1993, Scorpia criticized the middle of the game and the hunt for the pirate map, but stated that it was "definitely worth your time".[20]

Dragon gave the MS-DOS version 5 out of 5 stars,[13] but only 3 out of 5 stars for the Super NES version.[14] The editors of Strategy Plus named Ultima VI the best role-playing game of 1990. However, Editor-in-Chief Brian Walker wrote at the time, "If any genre is in need of a shake up, this is surely it. Like wargames, role-playing games are suffering from too literal conversions of the pen and paper systems." He argued that the genre had become bland and repetitive, and remarked that "Ultima VI took role-playing as far it could go within these [usual] parameters, offering as it did, brilliant graphics and a consistent world."[21][22]

The One gave the Amiga version of Ultima VI an overall score of 91%, criticising the amount of disk swapping throughout the game, and that to begin the game "you have to decompact the game to four spare floppies", further frustrated by the fact that this process needs to be repeated if the player creates a new character. The One furthermore states that "Ultima VI is not a fast game by any means and the frequent disk accessing and swapping makes two drives a necessity", but goes on to say that "given Ultima VI's incredible scale and scope it's a miracle that it made it onto the Amiga at all." The One praises Ultima VI's size, gameplay, and design, expressing that "There's no other RPG that comes within a mile of matching Ultima VI's huge depth and amazingly real atmosphere."[15]

Computer Gaming World nominated Ultima VI for its 1990 "Role-Playing Game of the Year" award, which went to Starflight 2: Trade Routes of the Cloud Nebula. The magazine highlighted Ultima VI's "interesting and important story, dynamite graphics ... and incredible detail".[16] In 1992, Computer Gaming World added Ultima VI to the magazine's Hall of Fame for games that readers highly rated over time.[17] In 1996 the magazine ranked it as the 44th best game of all time, stating that Ultima VI "hit new heights in virtuality with the defined objects in the game world" and "also presented a brilliant treatise on the danger of prejudice".[23]

Fan remakes

A fan-made recreation of Ultima VI using the Dungeon Siege engine, The U6 Project (aka Archon), was released on 5 July 2010. Another remake project uses the Exult engine, using graphics from Ultima VII. Ultima 6 Online is an MMO version of Ultima VI.[24]

References

- ↑ "Software Plus" (in en). April 5, 1990. https://newspapers.com/image/263386207/?terms=%22ultima%20vi%22&match=1. "Ultima VI (IBM NEW!) It's Hot!"

- ↑ See "Gargish Virtues " at the Ultima Codex

- ↑ "Ultima Collectors Guide - Ultima VI - C64". http://www.ultimacollectors.info/u6_c64_1.htm.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "The Official Book Of Ultima". 17 September 1990. https://archive.org/details/TheOfficialBookOfUltima.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Computer Gaming World, issue 68 (February 1990), pages 34 & 38

- ↑ Maher, Jimmy (2017-04-07). "Ultima VI". http://www.filfre.net/2017/04/ultima-vi/.

- ↑ "Ultima Guide OfficialBookOfUltima". https://archive.org/details/Ultima_Guide_OfficialBookOfUltima.

- ↑ "Ultima 6 For FM-TOWNS Sound Files". 15 June 2004. http://originmuseum.solsector.net/stories/story2.htm.

- ↑ "Special Limited Edition Ultima VI Offer". Computer Gaming World: 16. March 1990. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1990&pub=2&id=69. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ↑ Nuvie

- ↑ "phorum - Exult Discussion - New patch - Ultima 6 conversion". https://exult.sourceforge.net/forum/read.php?f=1&i=25755&t=25755.

- ↑ Zzap!64 review, Newsfield Publications, issue 73, page 54

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Lesser, Hartley; Lesser, Patricia; Lesser, Kirk (October 1990). "The Role of Computers". Dragon (162): 47–51. https://archive.org/stream/DragonMagazine260_201801/DragonMagazine162#page/n47/mode/2up.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Petersen, Sandy (August 1994). "Eye of the Monitor". Dragon (208): 61–66.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Ultima VI Review". The One (emap Images) (44): 48–49. May 1992. https://archive.org/details/theone-magazine-44/page/n47.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "CGW's Game of the Year Awards". Computer Gaming World (74): 70, 74. September 1990.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "The CGW Poll". Computer Gaming World: 48. April 1992. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1992&pub=2&id=93. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ The Official Book Of Ultima (second ed.). 1990. p. 35. https://archive.org/details/TheOfficialBookOfUltima/page/n47.

- ↑ Scorpia (June 1990). "Ultima VI". Computer Gaming World: 11. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1990&pub=2&id=72. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ↑ Scorpia (October 1993). "Scorpia's Magic Scroll Of Games". Computer Gaming World: 34–50. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1993&pub=2&id=111. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ Staff (January 1991). "Strategy Plus Awards 1990". Strategy Plus (4): 30, 31.

- ↑ Walker, Brian (January 1991). "1990: A Walkthru". Strategy Plus (4): 29, 32.

- ↑ "150 Best Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World: 64–80. November 1996. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1996&pub=2&id=148. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "Ultima 6 Online - Free Online MMORPG and MMO Games List - OnRPG". http://www.onrpg.com/MMO/Ultima-6-Online.

External links

- MobyGames is a commercial database website that catalogs information on video games and the people and companies behind them via crowdsourcing. This includes over 300,000 games for hundreds of platforms.[1] Founded in 1999, ownership of the site has changed hands several times. It has been owned by Atari SA since 2022.

Features

Edits and submissions to the site (including screenshots, box art, developer information, game summaries, and more) go through a verification process of fact-checking by volunteer "approvers".[2] This lengthy approval process after submission can range from minutes to days or months.[3] The most commonly used sources are the video game's website, packaging, and credit screens. There is a published standard for game information and copy-editing.[4] A ranking system allows users to earn points for contributing accurate information.[5]

Registered users can rate and review games. Users can create private or public "have" and "want" lists, which can generate a list of games available for trade with other registered users. The site contains an integrated forum. Each listed game can have its own sub-forum.

History

MobyGames was founded on March 1, 1999, by Jim Leonard and Brian Hirt, and joined by David Berk 18 months later, the three of which had been friends since high school.[6][7] Leonard had the idea of sharing information about computer games with a larger audience. The database began with information about games for IBM PC compatibles, relying on the founders' personal collections. Eventually, the site was opened up to allow general users to contribute information.[5] In a 2003 interview, Berk emphasized MobyGames' dedication to taking video games more seriously than broader society and to preserving games for their important cultural influence.[5]

In mid-2010, MobyGames was purchased by GameFly for an undisclosed amount.[8] This was announced to the community post factum , and the site's interface was given an unpopular redesign.[7] A few major contributors left, refusing to do volunteer work for a commercial website.{{Citation needed|date=June 2025} On December 18, 2013, MobyGames was acquired by Jeremiah Freyholtz, owner of Blue Flame Labs (a San Francisco-based game and web development company) and VGBoxArt (a site for fan-made video game box art).[9] Blue Flame Labs reverted MobyGames' interface to its pre-overhaul look and feel,[10] and for the next eight years, the site was run by Freyholtz and Independent Games Festival organizer Simon Carless.[7]

On November 24, 2021, Atari SA announced a potential deal with Blue Flame Labs to purchase MobyGames for $1.5 million.[11] The purchase was completed on 8 March 2022, with Freyholtz remaining as general manager.[12][13][14] Over the next year, the financial boost given by Atari led to a rework of the site being built from scratch with a new backend codebase, as well as updates improving the mobile and desktop user interface.[1] This was accomplished by investing in full-time development of the site instead of its previously part-time development.[15]

In 2024, MobyGames began offering a paid "Pro" membership option for the site to generate additional revenue.[16] Previously, the site had generated income exclusively through banner ads and (from March 2014 onward) a small number of patrons via the Patreon website.[17]

See also

- IGDB – game database used by Twitch for its search and discovery functions

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sheehan, Gavin (2023-02-22). "Atari Relaunches The Fully Rebuilt & Optimized MobyGames Website". https://bleedingcool.com/games/atari-relaunches-the-fully-rebuilt-optimized-mobygames-website/.

- ↑ Litchfield, Ted (2021-11-26). "Zombie company Atari to devour MobyGames". https://www.pcgamer.com/zombie-company-atari-to-devour-mobygames/.

- ↑ "MobyGames FAQ: Emails Answered § When will my submission be approved?". Blue Flame Labs. 30 March 2014. http://www.mobygames.com/info/faq7#g1.

- ↑ "The MobyGames Standards and Practices". Blue Flame Labs. 6 January 2016. http://www.mobygames.com/info/standards.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Miller, Stanley A. (2003-04-22). "People's choice awards honor favorite Web sites". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ↑ "20 Years of MobyGames" (in en). 2019-02-28. https://trixter.oldskool.org/2019/02/28/20-years-of-mobygames/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Plunkett, Luke (2022-03-10). "Atari Buys MobyGames For $1.5 Million". https://kotaku.com/mobygames-retro-credits-database-imdb-atari-freyholtz-b-1848638521.

- ↑ "Report: MobyGames Acquired By GameFly Media". Gamasutra. 2011-02-07. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/report-mobygames-acquired-by-gamefly-media.

- ↑ Corriea, Alexa Ray (December 31, 2013). "MobyGames purchased from GameFly, improvements planned". http://www.polygon.com/2013/12/31/5261414/mobygames-purchased-from-gamefly-improvements-planned.

- ↑ Wawro, Alex (31 December 2013). "Game dev database MobyGames getting some TLC under new owner". Gamasutra. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/game-dev-database-mobygames-getting-some-tlc-under-new-owner.

- ↑ "Atari invests in Anstream, may buy MobyGames". November 24, 2021. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2021-11-24-atari-invests-in-anstream-may-buy-mobygames.

- ↑ Rousseau, Jeffrey (2022-03-09). "Atari purchases Moby Games". https://www.gamesindustry.biz/atari-purchases-moby-games.

- ↑ "Atari Completes MobyGames Acquisition, Details Plans for the Site's Continued Support". March 8, 2022. https://www.atari.com/atari-completes-mobygames-acquisition-details-plans-for-the-sites-continued-support/.

- ↑ "Atari has acquired game database MobyGames for $1.5 million" (in en-GB). 2022-03-09. https://www.videogameschronicle.com/news/atari-has-acquired-game-database-mobygames-for-1-5-million/.

- ↑ Stanton, Rich (2022-03-10). "Atari buys videogame database MobyGames for $1.5 million". https://www.pcgamer.com/atari-buys-videogame-database-mobygames-for-dollar15-million/.

- ↑ Harris, John (2024-03-09). "MobyGames Offering “Pro” Membership". https://setsideb.com/mobygames-offering-pro-membership/.

- ↑ "MobyGames on Patreon". http://www.patreon.com/mobygames.

Wikidata has the property:

|

External links

- No URL found. Please specify a URL here or add one to Wikidata.

|

- Ultima VI: The False Prophet can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive

- Ultima VI: The False Prophet at the Codex of Ultima Wisdom wiki

|