Unsolved:Levitation (paranormal)

| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

Levitation or transvection, in the paranormal or religious context, is the claimed ability to raise a human body or other object into the air by mystical means.

While believed in some religious and New Age communities to occur due to supernatural, psychic, or "energetic" phenomena, there is no scientific evidence of levitation occurring. Alleged cases of levitation can usually be explained by natural causes such as trickery, illusion, and hallucination.[1][2][3][4][5]

Religious views

Various religions have claimed examples of levitation amongst their followers. This is generally used either as a demonstration of the validity or power of the religion,[6] or as evidence of the holiness or adherence to the religion of the particular levitator.

Buddhism

- It is recounted as one of the Miracles of Buddha that Gautama Buddha walked on water levitating (crossed legs) over a stream in order to convert a brahmin to Buddhism.[6]

- Yogi Milarepa, a Vajrayana Buddhist guru, was rumored to have possessed a range of additional abilities during levitation, such as the ability to walk, rest and sleep; however, such were deemed as occult powers.[citation needed]

Christianity

- According to three gospels, Jesus walked on the water of Lake Galilee to meet his disciples who were in a boat.[7]

- Saint Mary of Egypt (c. 344 – c. 421), walked across the river Jordan according to her hagiographer, the hermit Zosimas of Palestine[8]

- Saint Bessarion of Egypt (died c. 466), is said to have walked across the waters of the river Nile[9][10]

- Francis of Assisi (c. 1182 – 1226), founder of the Franciscan Order, is recorded as having been "suspended above the earth, often to a height of three, and often to a height of four cubits". This is about 1.3 to 1.8 m (4 ft 3 in–5 ft 11 in).[11]

- Saint Catherine of Siena (1347–1380), a nun of the Third Order of Saint Dominic and Doctor of the Church, was said to have levitated while in prayer, and a priest claimed to have seen the Holy Communion's Eucharist wafer flying from his hand straight to Catherine's hand.[12][13][14]

- Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582), a Carmelite nun and Doctor of the Church, claimed to have levitated at a height of about a 1.5 feet (0.46 m) for an extended period somewhat less than an hour, in a state of mystical rapture. She called the experience a "spiritual visitation".[15]

- Saint Martín de Porres (1579–1639), a lay brother of the Dominican Order, claimed psychic powers of bilocation, being able to pass through closed doors (teleportation), and levitation.[16]:227

- Joseph of Cupertino (1603–1663), a Franciscan Friar, reportedly levitated high in the air, for extended periods of more than an hour, on many occasions.[17]

- Alphonsus Liguori (1696–1787), when preaching at Foggia, was purportedly lifted before the eyes of the whole congregation several feet from the ground.[16]:13

- Girolamo Savonarola, sentenced to death, allegedly rose off the floor of his cell into midair and remained there for some time.[18]

- Seraphim of Sarov (1759–1833), Russian Orthodox saint, allegedly had a gift to levitate over the ground for some time, witnessed by many educated people of his time, including the emperor Alexander I of Russia.[19]

- Mariam Baouardy (Arabic: مريم بواردي; or "Mary of Jesus Crucified", 1846–1878), a Discalced Carmelite nun of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, experienced frequent ecstasies. She was purportedly seen levitating more than once by others: for example, in the garden of the monastery during times of private prayer, when living in the Carmelite monastery at Pau, in France.[20][page needed]

- "Demonic" levitation in Christianity

- Simon Magus is recorded in the Acts of Peter as levitating above the Forum in Rome in order to prove himself to be a god. The apostle Peter intervenes, causing Magus to drop from the sky, breaking his legs "in three parts".[21]

- Clara Germana Cele, a young South African girl, in 1906 reportedly levitated in a rigid position. The effect was apparently only reversed by the application of Holy water, leading to belief that it was caused by demonic possession.[15]:328

- Magdalena de la Cruz (1487–1560), a Franciscan nun of Cordova, Spain.[22]

- Margaret Rule, a young Boston girl in the 1690s who was believed to be harassed by evil forces shortly after the Salem Witchcraft Trials, reportedly levitated from her bed in the presence of a number of witnesses.[23]

Gnosticism

- Simon Magus, a Gnostic who claimed to be an incarnation of God (as conceived by the Gnostics), reportedly had the ability to levitate, along with many other magical powers.[24]

- Mani, founder of Manichaeism, was reputed to be able to levitate.[25]

Hellenism

- It was believed in Hellenism (the pagan religion of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome) on the testimony of Philostratus that upon his death, Apollonius of Tyana underwent heavenly assumption by levitating into Elysium.[26]

Hinduism

- In Hinduism, it is believed that some Hindu mystics and gurus who have achieved certain spiritual powers (called siddhis) are able to levitate. In Sanskrit, the power of levitation is called laghiman ('lightness') or dardura-siddhi (the 'frog power').[27] Yogananda's book Autobiography of a Yogi has accounts of Hindu Yogis who levitated in the course of their meditation.

- Yogi Subbayah Pullavar was reported to have levitated into the air for four minutes in front of a crowd of 150 witnesses on June 6, 1936. He was seen suspended horizontally several feet above the ground, in a trance, lightly resting his hand on top of a cloth-covered stick. Pullavar's arms and legs could not be bent from their locked position once on the ground. The illusion was created by a simple method in which the person seen to levitate is supported by a cantilevered platform held up by an iron rod camouflaged in some way.[5]

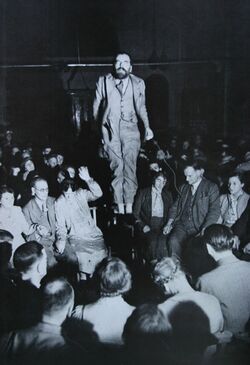

Levitation by mediums

Many mediums have claimed to have levitated during séances, especially in the 19th century in Britain and America. Many have been shown to be frauds, using wires and stage magic tricks.[28] Daniel Dunglas Home, a prolific and well-documented levitator of himself and other objects, was said by spiritualists to levitate outside a window. Skeptics have disputed such claims.[29] The researchers Joseph McCabe and Trevor H. Hall exposed the "levitation" of Home as nothing more than him moving across a connecting ledge between two iron balconies.[30]

The magician Joseph Rinn gave a full account of fraudulent behavior observed in a séance of Eusapia Palladino and explained how her levitation trick had been performed. Milbourne Christopher summarized the exposure:

- "Joseph F. Rinn and Warner C. Pyne, clad in black coveralls, had crawled into the dining room of Columbia professor Herbert G. Lord's house while a Palladino seance was in progress. Positioning themselves under the table, they saw the medium's foot strike a table leg to produce raps. As the table tilted to the right, due to pressure of her right hand on the surface, they saw her put her left foot under the left table leg. Pressing down on the tabletop with her left hand and up with her left foot under the table leg to form a clamp, she lifted her foot and "levitated" the table from the floor."[31]

The levitation trick of the medium Jack Webber was exposed by the magician Julien Proskauer. According to Proskauer he would use a telescopic reaching rod attached to a trumpet to levitate objects in the séance room.[32] The physicist Edmund Edward Fournier d'Albe investigated the medium Kathleen Goligher at many sittings and concluded that no paranormal phenomena such as levitation had occurred with Goligher and stated he had found evidence of fraud. D'Albe had claimed the ectoplasm substance in the photographs of Goligher from her séances were made from muslin.[33][34][35][36]

In photography

A person photographed while bouncing may appear to be levitating. This optical illusion is used by religious groups and by spiritualist mediums, claiming that their meditation techniques allow them to levitate in the air. Usually telltale signs can be found in the photography indicating that the subject was in the act of bouncing, like blurry body parts, a flailing scarf, hair being suspended in the air, etc.[3]

Levitation in popular culture

Literature

- Incidents in my Life autobiography by Daniel Dunglas Home

- Mr. Vertigo novel by Paul Auster

Film

- The Exorcist (1973), directed by William Friedkin

- Ghostbusters (1984), directed by Ivan Reitman

- The Boy Who Could Fly (1986), directed by Nick Castle

- Candyman film series directed by Bernard Rose (1992); Bill Condon (1995); Turi Meyer (1999); Nia DaCosta (2021)

TV shows

- Stranger Things, season 4 (2022)

See also

References

- ↑ Stein, Gordon (1996). The Encyclopedia of the Paranormal (2nd ed.). Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 9781573920216.

- ↑ Carroll, Robert Todd (2003). The Skeptic's Dictionary: A Collection of Strange Beliefs, Amusing Deceptions, and Dangerous Delusions. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. p. 198. ISBN 9780471272427. https://archive.org/details/skepticsdictiona00carr_024. "Levitation is the act of ascending into the air and floating in apparent defiance of gravity. Spiritual masters or fakirs are often depicted levitating. Some take the ability to levitate as a sign of blessedness. Others see levitation as a conjurer's trick. No one really levitates; they just appear to do so. Clever people can use illusion, "invisible string", and magnets to make things appear to levitate."

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nickell, Joe (2005). Camera Clues: A Handbook for Photographic Investigation. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. p. 177. ISBN 9780813191249. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZQS91E0d0B8C&q=levitation+paranormal&pg=PA177. "Some claims — of levitation, for instance — may be performed either as an illusion for an audience, as a magician's stage trick, or for the camera."

- ↑ Smith, Jonathan C. (2010). Pseudoscience and Extraordinary Claims of the Paranormal: A Critical Thinker's Toolkit. Malden, Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405181228.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Livingston, James D. (2011) (in en). Rising Force. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674061095. https://books.google.com/books?id=wzyWVtK0yNgC&q=PUllavar+&pg=PA4. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Schulberg, Lucille (1968). Historic India. New York: Time-Life Books. p. 94. ISBN 9780682244008. https://archive.org/details/historicindia00schu.

- ↑ "Matthew 14:22–33 KJV – And straightway Jesus constrained his". Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Matthew+14%3A22-33&version=KJV.

- ↑ *

MacRory, Joseph (1910). "St. Mary of Egypt". in Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

MacRory, Joseph (1910). "St. Mary of Egypt". in Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ↑ "St. Bessarion the Great, wonderworker of Egypt (466)". Holytrinityorthodox.com. 2007-02-22. http://www.holytrinityorthodox.com/calendar/los/February/20-06.htm.

- ↑ Catholic Online. "St. Bessarion – Saints & Angels – Catholic Online". Catholic.org. http://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=564.

- ↑ Summers, Montague (2000). Witchcraft and Black Magic. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. p. 200. ISBN 0486411257. https://archive.org/details/witchcraftblackm0000summ.

- ↑ "St. Catherine of Siena's Severed Head" (in en). http://www.atlasobscura.com/places/st-dominics-basilica.

- ↑ Egan, Jennifer (May 16, 1999). "The Shadow of the Millennium Women: Power Suffering". https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/magazine/millennium/m2/egan.html.

- ↑ Reda, Mario; Saco, Giuseppe (January 28, 2010). "Anorexia and the Holiness of Saint Catherine of Siena" (in en-US). Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture vol. 8 Issue 1. https://www.medievalists.net/2010/01/anorexia-and-the-holiness-of-saint-catherine-of-siena/.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (2001). Encyclopedia of the Strange, Mystical & Unexplained. New York: Gramercy Books. p. 327. ISBN 9780517162781.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (2001). The Encyclopedia of Saints. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 1438130260. https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofsa00guil.

- ↑ Michell, John; Rickard, Bob (2000). Unexplained Phenomena: A Rough Guide Special (1st ed.). London: Rough Guides. ISBN 1858285895.

- ↑ Villari, Pasquale (2006). Life and Times of Girolamo Savonarola. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1417967501.

- ↑ Zander, Valentine (1975). St. Seraphim of Sarov (3rd ed.). Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. pp. 79–81. ISBN 9780913836286. https://books.google.com/books?id=XvtVjrQjlakC&pg=PA79.

- ↑ Brunot, Amédée (2009). Mariam, la petite Arabe: soeur Marie de Jésus-Crucifié, 1846–1878, proclamée Bienheureuse le 13 novembre 1983 par Jean-Paul II. Paris: Salvator. ISBN 9782706706684.

- ↑ "The Acts of Peter". http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/actspeter.html.

- ↑ Ahlgren, Gillian T.W. (1998). Teresa of Avila and the Politics of Sanctity. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 21. ISBN 080148572X.

- ↑ Roach, Marilynne K. (2002). The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-by-Day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege (1st ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 442. ISBN 9781589791329. https://archive.org/details/salemwitchtrials00mari.

- ↑ Christiansen, Jørgen (1999). The History of Mind Control: From Ancient Times Until Now. Valby: Turtledove Book Company. p. 25. ISBN 8798753703.

- ↑ Sundermann, Werner (2009), Mani, the founder of the religion of Manicheism in the 3rd century AD, Sundermann, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/mani-founder-manicheism

- ↑ Hornblower, Simon (2012). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0199545568.

- ↑ Bowker, John (2000). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 259, 567, 576. ISBN 019861053X. https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780192800947.

- ↑ Brandon, Ruth (1984). The Spiritualists: The Passion for the Occult in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Buffalo, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 9780879752699.

- ↑ Stein, Gordon (1993). The Sorcerer of Kings: The Case of Daniel Dunglas Home and William Crookes. Buffalo, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 9780879758639.

- ↑ Smith, F. B. (1 January 1986). "Review of The Enigma of Daniel Home: Medium or Fraud?; The Spiritualists: The Passion for the Occult in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries; The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850–1914". Victorian Studies 29 (4): 613–614.

- ↑ Christopher, Milbourne (1979). Search for the Soul (1st ed.). New York: Crowell. p. 47. ISBN 9780690017601. https://archive.org/details/searchforsoul0000chri.

- ↑ Proskauer, Julien J. (1946). The Dead Do Not Talk. Harper & Brothers. p. 94.

- ↑ Fournier a'Albe, Edmund Edward (1922). The Goligher Circle. J. M. Watkins. p. 37.

- ↑ Franklyn, Julian (1935). A Survey of the Occult. Whitefish, Montana: Kessinger. p. 383. ISBN 9780766130074.

- ↑ Bechhofer Roberts, C. E. (1932). The Truth about Spiritualism. Kessinger Publishing. p. 128. ISBN 9781417981281.

- ↑ Jolly, Martyn (2006). Faces of the Living Dead: The Belief in Spirit Photography (1st ed.). London: British Library. pp. 84–86. ISBN 9780712348997.

Further reading

- John Booth (1986). Psychic Paradoxes. Buffalo, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 0879753587.

- Andrew Neher (1990). Paranormal and Transcendental Experience: A Psychological Examination (2nd ed.). New York: Dover. ISBN 0486261670. https://archive.org/details/paranormaltransc00nehe.

- James Randi (1987). "Chapter 5: "The Giggling Guru: A Master of Levity"". Flim-Flam! Psychics, ESP, Unicorns, and Other Delusions (9th ed.). Buffalo, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 0879751983.

- Gordon Stein (Spring 1989). "The Levitation of the Lore". Skeptical Inquirer 13 (2): 277–288.

External links

- Levitation by Mark Edward

- Levitation – Skeptic's Dictionary

- The Flying Mystics of Tibetan Buddhism art exhibit, Oglethorpe University, 2004

|