Unsolved:Malthusian catastrophe

| It has been suggested that Malthusian trap be merged into this page. (Discuss) Proposed since July 2020. |

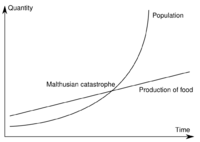

A Malthusian catastrophe (also known as Malthusian check, Malthusian crisis, Malthusian spectre or Malthusian crunch) occurs when population growth outpaces agricultural production.

Thomas Malthus

In 1798, Thomas Malthus wrote:

Famine seems to be the last, the most dreadful resource of nature. The power of population is so superior to the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race. The vices of mankind are active and able ministers of depopulation. They are the precursors in the great army of destruction, and often finish the dreadful work themselves. But should they fail in this war of extermination, sickly seasons, epidemics, pestilence, and plague advance in terrific array, and sweep off their thousands and tens of thousands. Should success be still incomplete, gigantic inevitable famine stalks in the rear, and with one mighty blow levels the population with the food of the world.—Thomas Malthus, 1798. An Essay on the Principle of Population. Chapter VII, p. 61[1]

The dramatic imagery of the final sentence should not obscure the force of the earlier lines. Malthus is suggesting that the growth of population need not be restricted by plague or famine; more quotidian pressures work more quietly to slow population growth.

Preventive vs. positive

Malthus proposed two kinds of population checks: preventive and positive.

A preventive check is a conscious decision to delay marriage or abstain from procreation based on a lack of resources.[2] Malthus argued that man is incapable of ignoring the consequences of uncontrolled population growth, and would intentionally avoid contributing to it.[2] According to Malthus, a positive check is any event or circumstance that shortens the human life span. The primary examples of this are war, plague and famine.[2] However, poor health and economic conditions are also considered instances of positive checks.[3]

Neo-Malthusian theory

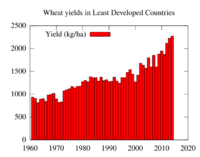

After World War II, mechanized agriculture produced a dramatic increase in productivity of agriculture and the Green Revolution greatly increased crop yields, expanding the world's food supply while lowering food prices. In response, the growth rate of the world's population accelerated rapidly, resulting in predictions by Paul R. Ehrlich, Simon Hopkins,[5] and many others of an imminent Malthusian catastrophe. However, populations of most developed countries grew slowly enough to be outpaced by gains in productivity.

By the early 21st century, many technologically-developed countries had passed through the demographic transition, a complex social development encompassing a drop in total fertility rates in response to various fertility factors, including lower infant mortality, increased urbanization, and a wider availability of effective birth control.

On the assumption that the demographic transition is now spreading from the developed countries to less developed countries, the United Nations Population Fund estimates that human population may peak in the late 21st century rather than continue to grow until it has exhausted available resources.[6]

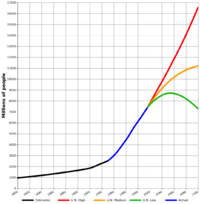

Historians have estimated the total human population back to 10,000 BC.[7] The figure on the right shows the trend of total population from 1800 to 2005, and from there in three projections out to 2100 (low, medium, and high).[6] The United Nations population projections out to 2100 (the red, orange, and green lines) show a possible peak in the world's population occurring by 2040 in the first scenario, and by 2100 in the second scenario, and never ending growth in the third.

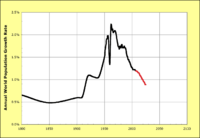

The graph of annual growth rates in world population (outlined in yellow) shows exponential growth at varying rates. Any point above zero shows exponential growth. A constant exponential growth would be a horizontal straight line at any height above 0. A stable population has a growth rate of 0. Population decline would take the curve below the chart into the yellow border. The hump in the graph began about 1920, peaked in the mid-1960s, and for the last 40 years the rate of exponential growth has been steadily declining. The downward direction of the curve does not mean that the population is declining, only that it is growing less quickly. The sharp fluctuation between 1959 and 1960 was due to the combined effects of the Great Leap Forward and a natural disaster in China.[8] Also visible on this graph are the effects of the Great Depression, the two world wars, and possibly also the 1918 flu pandemic.

A 2002 study[10] by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization predicts that world food production will be in excess of the needs of the human population by the year 2030; however, that source also states that hundreds of millions will remain hungry (presumably due to economic realities and political issues).

A 2004 study by a group of prominent economists and ecologists, including Kenneth Arrow and Paul Ehrlich[11] suggests that the central concerns regarding sustainability have shifted from population growth to the consumption/savings ratio, due to shifts in population growth rates since the 1970s. Empirical estimates show that public policy (taxes or the establishment of more complete property rights) can promote more efficient consumption and investment that are sustainable in an ecological sense; that is, given the current (relatively low) population growth rate, the Malthusian catastrophe can be avoided by either a shift in consumer preferences or public policy that induces a similar shift.

A study conducted in 2009[12] said that food production will have to increase by 70% over the next 40 years, and food production in the developing world will need to double.[13] This is a result of the increasing population (world population will increase to 9.1 billion in 2050, where there are just 7.8 billion people today). Another issue is that the effects of global warming (floods, droughts, extreme weather events, ...) will negatively affect food production, in such a degree even that food shortages are likely to occur in the coming decades.[14][15] As a result, we will need to use the scarce natural resources more efficiently and adapt to climate change.[16] Lastly, some things (such as the increase in agricultural production for 1st generation biofuels) has not been taken into account in FAO's forecast.[17]

Criticism

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels argued that Malthus failed to recognize a crucial difference between humans and other species. In capitalist societies, as Engels put it, scientific and technological "progress is as unlimited and at least as rapid as that of population".[18] Marx argued, even more broadly, that the growth of both a human population in toto and the "relative surplus population" within it, occurred in direct proportion to accumulation.[19]

Henry George in Progress and Poverty (1879) criticized Malthus's view that population growth was a cause of poverty, arguing that poverty was caused by the concentration of ownership of land and natural resources. George noted that humans are distinct from other species, because unlike most species humans can use their minds to leverage the reproductive forces of nature to their advantage. He wrote, "Both the jayhawk and the man eat chickens; but the more jayhawks, the fewer chickens, while the more men, the more chickens."[20]

D. E. C. Eversley observed that Malthus appeared unaware of the extent of industrialization, and either ignored or discredited the possibility that it could improve living conditions of the poorer classes.[21]

Barry Commoner believed in The Closing Circle (1971) that technological progress will eventually reduce the demographic growth and environmental damage created by civilization. He also opposed coercive measures postulated by neo-malthusian movements of his time arguing that their cost will fall disproportionately on the low-income population who is struggling already.

Ester Boserup suggested that expanding population leads to agricultural intensification and development of more productive and less labor-intensive methods of farming. Thus, human population levels determines agricultural methods, rather than agricultural methods determining population.[22]

Environmentalist Stewart Brand summarized how the Malthusian predictions of The Population Bomb and The Limits to Growth failed to materialize due to radical changes in fertility:[23]

The theory’s Malthusian premise has been proven wrong since 1963, when the rate of population growth reached a frightening 2 percent a year but then began dropping. The 1963 inflection point showed that the imagined soaring J-curve of human increase was instead a normal S-curve. The growth rate was leveling off. No one thought the growth rate might go negative and the population start shrinking in this century without an overshoot and crash, but that is what is happening.

Short-term trends, even on the scale of decades or centuries, cannot prove or disprove the existence of mechanisms promoting a Malthusian catastrophe over longer periods. However, due to the prosperity of a major fraction of the human population at the beginning of the 21st century, and the debatability of the predictions for ecological collapse made by Paul R. Ehrlich in the 1960s and 1970s, some people, such as economist Julian L. Simon and medical statistician Hans Rosling questioned its inevitability.[24]

Joseph Tainter noted that science has diminishing marginal returns[25][incomplete short citation] and that scientific progress is becoming more difficult, harder to achieve, and more costly, which may reduce efficiency of the factors that prevented the Malthusian scenarios from happening in the past.

See also

- Antinatalism

- Demographic trap

- Global catastrophic risk

- Human overpopulation

- Malthusian trap

- Peak phosphorus

- Population cycle

- Overshoot (population)

- Olduvai theory

- r/K selection theory

Notes

- ↑ Oxford World's Classics reprint

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Malthus, Thomas Robert (1798). "An Essay on The Principle of Population". http://www.esp.org/books/malthus/population/malthus.pdf.

- ↑ Simkins, Charles (2001). "Can South Africa Avoid a Malthusian Positive Check?". Daedalus 130 (1): 123–150. PMID 19068951.

- ↑ Fischer, R. A.; Byerlee, Eric; Edmeades, E. O.. "Can Technology Deliver on the Yield Challenge to 2050". Expert Meeting on How to Feed the World (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations): 12. ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/012/ak977e/ak977e00.pdf.

- ↑ Hopkins, Simon (1966). A Systematic Foray into the Future. Barker Books. pp. 513–69.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "2004 UN Population Projections, 2004.". https://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/longrange2/WorldPop2300final.pdf.

- ↑ "Historical Estimates of World Population, U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2006.". Archived from the original on 2013-10-13. https://web.archive.org/web/20131013110506/http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/worldhis.html.

- ↑ "International Data Base". https://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb/.

- ↑ Data source: http://faostat3.fao.org/download/Q/QI/E, see graph metadata for further details.

- ↑ World agriculture 2030: Global food production will exceed population growth August 20, 2002.

- ↑ Arrow, K., P. Dasgupta, L. Goulder, G. Daily, P. Ehrlich, G. Heal, S. Levin, K. Mäler, S. Schneider, D. Starrett and B. Walker, "Are We Consuming Too Much" Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(3), 147–72, 2004.

- ↑ How to feed the world in 2050

- ↑ 2050: A third more mouths to feed

- ↑ Climate Change and Land report

- ↑ Climate Change Threatens the World’s Food Supply, United Nations Warns

- ↑ Food production 'must rise 70%'

- ↑ FAO says Food Production must Rise by 70%

- ↑ Engels, Friedrich."Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy", Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, 1844, p. 1.

- ↑ Karl Marx (transl. Ben Fowkes), Capital Volume 1, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1976 (originally 1867), pp. 782–802.

- ↑ "Progress and Poverty, Chapter 7". http://www.henrygeorge.org/pchp7.htm.

- ↑ Charles., Eversley, David Edward (1959). Social theories of fertility and the Malthusian debate. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780837176284. OCLC 1287575.

- ↑ Boserup, Ester (1966). "The Conditions of Agricultural Growth. The Economics of Agrarian Change under Population Pressure". Population 21 (2). doi:10.2307/1528968.

- ↑ Brand, Stewart (2010). Whole Earth Discipline. ISBN 978-1843548164.

- ↑ Simon, Julian L, "More People, Greater Wealth, More Resources, Healthier Environment", Economic Affairs: J. Inst. Econ. Affairs, April 1994.

- ↑ Tainter, Joseph. The Collapse of Complex Societies, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2003.

References

- Korotayev A., Malkov A., Khaltourina D. Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Compact Macromodels of the World System Growth. Moscow: URSS, 2006. ISBN 5-484-00414-4

- Korotayev A., Malkov A., Khaltourina D. Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Secular Cycles and Millennial Trends. Moscow: URSS, 2006. ISBN 5-484-00559-0 See especially Chapter 2 of this book

- Korotayev A. & Khaltourina D. Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Secular Cycles and Millennial Trends in Africa. Moscow: URSS, 2006. ISBN 5-484-00560-4

- Malthus, Thomas Robert (1798). "An Essay on the Principle of Population". Electronic Scholarly Publishing Project (London). http://www.esp.org/books/malthus/population/malthus.pdf. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Turchin, P., et al., eds. (2007). History & Mathematics: Historical Dynamics and Development of Complex Societies. Moscow: KomKniga. ISBN 5-484-01002-0

- A Trap At The Escape From The Trap? Demographic-Structural Factors of Political Instability in Modern Africa and West Asia. Cliodynamics 2/2 (2011): 1–28.

External links

- Essay on life of Thomas Malthus

- Malthus' Essay on the Principle of Population

- David Friedman's essay arguing against Malthus' conclusions

- United Nations Population Division World Population Trends homepage