Biology:Lingzhi mushroom

| Lingzhi mushroom | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Polyporales |

| Family: | Ganodermataceae |

| Genus: | Ganoderma |

| Species: | G. lucidum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ganoderma lucidum (Sheng H. Wu, Y. Cao & Y.C. Dai) (2012)

| |

| Lingzhi mushroom | |

|---|---|

| Mycological characteristics | |

| pores on hymenium | |

| cap is offset or indistinct | |

| hymenium attachment is irregular or not applicable | |

| stipe is bare or lacks a stipe | |

| spore print is brown | |

| ecology is saprotrophic or parasitic | |

| edibility: edible | |

The lingzhi mushroom is a polypore fungus ("bracket fungus") belonging to the genus Ganoderma. Its red-varnished, kidney-shaped cap and peripherally inserted stem gives it a distinct fan-like appearance. When fresh, the lingzhi is soft, cork-like, and flat. It lacks gills on its underside, and instead releases its spores via fine pores. Depending on the age, the pores on its underside may be white or brown.[1]

Lingzhi mushroom is used in traditional Chinese medicine.[2][3] In nature, it grows at the base and stumps of deciduous trees, especially that of the maple. Only two or three out of 10,000 such aged trees will have lingzhi growth, and therefore its wild form is extremely rare.[citation needed] Today, lingzhi is effectively cultivated on hardwood logs or sawdust/woodchips.

Taxonomy and ecology

Lingzhi, also known as reishi, is the ancient "mushroom of immortality", revered for over 2,000 years. Uncertainty exists about which Ganoderma species was most widely utilized as Lingzhi mushroom in ancient times, and likely a few different common species were considered interchangeable. However, in the most famous book of herbal medicine in China, the Bencao Gangmu (1578), a number of different lingzhi-like mushrooms were used for different purposes and defined by color. No exact current species can be attached to these ancient Lingzhi for certain, but according to Dai et al. (2017)[4], as well as other researchers and based on molecular work, red reishi is most likely to be Ganoderma lingzhi Sheng H. Wu, Y. Cao & Y.C. Dai (2012). This is the species that is most widely found in Chinese herb shops today, and the fruiting bodies are widely cultivated in China and shipped to many other countries. About 7-10 other Ganoderma species are also sold in some shops, but have different Chinese and Latin names and are considered different in their activity and functions. The differences are based on concentrations of triterpenes such as ganoderic acid and its derivatives which vary widely among species. Lingzhi was formerly known as Ganoderma lucidum (Curtis) P. Karst. (1881), first described by Curtis. G. lucidum is part of a species complex that encompasses several varieties and forms (Species Fungorum). Research on the genus is on-going, but a number of recent phylogentic analyses have been published in the last number of years. [5]

Nomenclature

Petter Adolf Karsten named the genus Ganoderma in 1881.[6] English botanist William Curtis gave the fungus its first binomial name, Boletus lucidus, in 1781.[7] The lingzhi's botanical names have Greek and Latin roots. Ganoderma derives from the Greek ganos (γανος; "brightness"), and derma (δερμα; "skin; together; shining skin").[8] The specific epithet, lucidum, is from Latin, meaning "shining".

With the advent of genome sequencing, the genus Ganoderma has undergone taxonomic reclassification. Prior to genetic analyses of fungi, classification was done according to morphological characteristics such as size and color. The internal transcribed spacer region of the Ganoderma genome is considered to be a standard barcode marker.[9]

Varieties

It was once thought that Ganoderma lucidum generally occurred in two growth forms: a large, sessile, specimen with a small or nonexistent stalk, found in North America, and a smaller specimen with a long, narrow stalk found mainly in the tropics. However, recent molecular evidence has identified the former, stalkless, form as a distinct species called G. sessile, a name given to North American specimens by William Alfonso Murrill in 1902.[5][10]

Environmental conditions play a substantial role in the lingzhi's manifest morphological characteristics. For example, elevated carbon dioxide levels result in stem elongation in lingzhi. Other formations include antlers without a cap, which may also be related to carbon dioxide levels. The three main factors that influence fruit body development morphology are light, temperature, and humidity. While water and air quality play a role in fruit body development morphology, they do so to a lesser degree.[11]

Habitat

Ganoderma lucidum and its close relative, Ganoderma tsugae, grow in the northern Eastern Hemlock forests. These two species of bracket fungus have a worldwide distribution in both tropical and temperate geographical regions, growing as a parasite or saprotroph on a wide variety of trees.[1] Similar species of Ganoderma have been found growing in the Amazon.[12]

In the wild, lingzhi grows at the base and stumps of deciduous trees, especially that of the maple.[13] Only two or three out of 10,000 such aged trees will have lingzhi growth, and therefore it is extremely rare in its natural form.[citation needed] Today, lingzhi is effectively cultivated on hardwood logs or sawdust/woodchips.[14]

History

The word lingzhi (靈芝) was first recorded in a fu (賦; "rhapsody; prose-poem") by the Han dynasty polymath Zhang Heng (CE 78–139). His Xijing fu (西京賦) (Western Metropolis Rhapsody) contains a description of the 104 BCE Jianzhang Palace of Emperor Wu of Han that parallels lingzhi with shijun (石菌; "rock mushroom"): "Raising huge breakers, lifting waves, That drenched the stone mushrooms on the high bank, And soaked the magic fungus on vermeil boughs."[15] The commentary by Xue Zong (d. 237) notes that these fungi were eaten as drugs of immortality.

The Shennong bencao jing (Divine Farmer's Classic of Pharmaceutics) of c.200–250 CE, classifies zhi into six color categories, each of which is believed to benefit the qi, or "life force", in a different part of the body: qingzhi (青芝; "Green Mushroom") for the liver, chizhi (赤芝; "Red Mushroom") for the heart, huangzhi (黃芝; "Yellow Mushroom") for the spleen, baizhi (白芝; "White Mushroom") for the lungs, heizhi (黑芝; "Black Mushroom") for the kidneys, and zizhi (紫芝; "Purple Mushroom") for the Essence. Commentators identify the red chizhi, or danzhi (丹芝; "cinnabar mushroom"), as the lingzhi.

Chi Zhi (Ganoderma rubra) is bitter and balanced. It mainly treats binding in the chest, boosts the heart qi, supplements the center, sharpens the wits, and [causes people] not to forget [i.e., improves the memory]. Protracted taking may make the body light, prevent senility, and prolong life so as to make one an immortal. Its other name is Dan Zhi (Cinnabar Ganoderma). It grows in mountains and valleys.[16][17]

While Chinese texts have recorded medicinal uses of lingzhi for more than 2,000 years, a few sources erroneously claim its use can be traced back more than 4,000 years.[18] Modern scholarship accepts neither the historicity of Shennong, "Divine Farmer", (legendary inventor of agriculture, traditionally c. 2737–2697 BCE) nor that he wrote the Shennong bencao jing.[citation needed]

The (1596) Bencao Gangmu (Compendium of Materia Medica) has a Zhi (芝) category that includes six types of zhi (calling the green, red, yellow, white, black, and purple mushrooms of the Shennong bencao jing the liuzhi (六芝; "six mushrooms") and sixteen other fungi, mushrooms, and lichens, including mu'er (木耳; "wood ear"; "cloud ear fungus", Auricularia auricula-judae). The author Li Shizhen classified these six differently colored zhi as xiancao (仙草; "immortality herbs"), and described the effects of chizhi ("red mushroom"): {{Quote|text=It positively affects the life-energy, or Qi of the heart, repairing the chest area and benefiting those with a knotted and tight chest. Taken over a long period of time, the agility of the body will not cease, and the years are lengthened to those of the Immortal Fairies.[19][20]

Stuart and Smith's classic study of Chinese herbology describes the zhi.

芝 (Chih) is defined in the classics as the plant of immortality, and it is therefore always considered to be a felicitous one. It is said to absorb the earthy vapors and to leave a heavenly atmosphere. For this reason, it is called 靈芝 (Ling-chih.) It is large and of a branched form, and probably represents Clavaria or Sparassis. Its form is likened to that of coral.[21]

The Bencao Gangmu does not list lingzhi as a variety of zhi, but as an alternate name for the shi'er (石耳; "stone ear", Umbilicaria esculenta) lichen. According to Stuart and Smith,

[The 石耳 Shih-erh is] edible, and has all of the good qualities of the 芝 (Chih), it is also being used in the treatment of gravel, and said to benefit virility. It is specially used in hemorrhage from the bowels and prolapse of the rectum. While the name of this would indicate that it was one of the Auriculariales, the fact that the name 靈芝 (Ling-chih) is also given to it might place it among the Clavariaceae.[21]

In Chinese art, the lingzhi symbolizes great health and longevity, as depicted in the imperial Forbidden City and Summer Palace.[22] It was a talisman for luck in the traditional culture of China, and the goddess of healing Guanyin is sometimes depicted holding a lingzhi mushroom.[20]

Regional names

| Regional names |

|---|

Chinese

The name of the lingzhi fungus has a two thousand-year-old history. The Old Chinese name 靈芝 was first recorded during the Han dynasty (206 BC – 9 AD). In the Chinese language, língzhī (灵芝) is a compound. It comprises líng (灵); "spirit, spiritual; soul; miraculous; sacred; divine; mysterious; efficacious; effective)" as, for example, in the name of the Lingyan Temple in Jinan, and zhī (芝); "(traditional) plant of longevity; fungus; seed; branch; mushroom; excrescence"). Fabrizio Pregadio notes, "The term zhi, which has no equivalent in Western languages, refers to a variety of supermundane substances often described as plants, fungi, or 'excrescences'."[23] Zhi occurs in other Chinese plant names, such as zhīmá (芝麻; "sesame" or "seed"), and was anciently used a phonetic loan character for zhǐ (芷; "Angelica iris"). Chinese differentiates Ganoderma species into chìzhī (赤芝; "red mushroom") G. lucidum, and zǐzhī (紫芝; "purple mushroom") G. japonicum.

Lingzhi has several synonyms. Of these, ruìcǎo (瑞草; "auspicious plant") (ruì 瑞; "auspicious; felicitous omen" with the suffix cǎo 草; "plant; herb") is the oldest; the Erya dictionary (c. 3rd century BCE) defines xiú 苬, interpreted as a miscopy of jūn (菌; "mushroom") as zhī (芝; "mushroom"), and the commentary of Guo Pu (276–324) says, "The [zhi] flowers three times in one year. It is a [ruicao] felicitous plant."[24] Other Chinese names for Ganoderma include ruìzhī (瑞芝; "auspicious mushroom"), shénzhī (神芝; "divine mushroom", with shen; "spirit; god' supernatural; divine"), mùlíngzhī (木灵芝) (with "tree; wood"), xiāncǎo (仙草; "immortality plant", with xian; "(Daoism) transcendent; immortal; wizard"), and língzhīcǎo (灵芝草) or zhīcǎo (芝草; "mushroom plant").

Since both Chinese ling and zhi have multiple meanings, lingzhi has diverse English translations. Renditions include "[zhi] possessed of soul power",[25] "Herb of Spiritual Potency" or "Mushroom of Immortality",[1] "Numinous Mushroom",[23] "divine mushroom",[26] "divine fungus",[27] "Magic Fungus",[15] and "Marvelous Fungus".[28]

English

In English, lingzhi or ling chih (sometimes spelled "ling chi", using the French EFEO Chinese transcription) is a Chinese loanword.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) gives the definition, "The fungus Ganoderma lucidum, believed in China to confer longevity and used as a symbol of this on Chinese ceramic ware.",[29] and identifies the etymology of the word as Chinese: líng, "divine" + zhī, "fungus". According to the OED, the earliest recorded usage of the Wade–Giles romanization ling chih is 1904,[30] and of the Pinyin lingzhi is 1980.

In addition to the transliterated loanword, English names include "glossy ganoderma" and "shiny polyporus".[31]

Japanese

The Japanese word reishi (霊芝) is a Sino-Japanese loanword deriving from the Chinese língzhī (灵芝; 靈芝). Its modern Japanese kanji, 霊, is the shinjitai ("new character form") of the kyūjitai ("old character form"), 靈. Synonyms for reishi are divided between Sino-Japanese borrowings and native Japanese coinages. Sinitic loanwords include literary terms such as zuisō (瑞草, from ruìcǎo; "auspicious plant") and sensō (仙草, from xiāncǎo; "immortality plant"). The Japanese writing system uses shi or shiba (芝) for "grass; lawn; turf", and take or kinoko (茸) for "mushroom" (e.g., shiitake). A common native Japanese name is mannentake (万年茸; "10,000-year mushroom"). Other Japanese terms for reishi include kadodetake (門出茸; "departure mushroom"), hijiridake (聖茸; "sage mushroom"), and magoshakushi (孫杓子; "grandchild ladle").

Korean

The Korean name, yeongji (영지; 靈芝) is also borrowed from, so a cognate with, the Chinese word língzhī (灵芝; 靈芝). It is often called yeongjibeoseot (영지버섯; "yeongji mushroom") in Korean, with the addition of the native word beoseot (버섯) meaning "mushroom". Other common names include bullocho (불로초, 不老草; "elixir grass") and jicho (지초; 芝草). According to color, yeongji mushrooms can be classified as jeokji (적지; 赤芝) for "red", jaji (자지; 紫芝) for "purple", heukji (흑지; 黑芝) for "black", cheongji (청지; 靑芝) for "blue" or "green", baekji (백지; 白芝) for "white", and hwangji (황지; 黃芝) for "yellow".

Thai

The Thai word het lin chue (เห็ดหลินจือ) is a compound of the native word het (เห็ด) meaning "mushroom" and the loanword lin chue (หลินจือ) from the Chinese língzhī (灵芝; 靈芝).

Vietnamese

The Vietnamese language word linh chi is a loanword from Chinese. It is often used with nấm, the Vietnamese word for "mushroom", thus nấm linh chi is the equivalent of "lingzhi mushroom".

Use

Medicinal

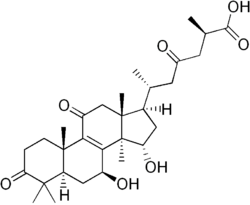

Ganoderma lucidum produces a group of triterpenes called ganoderic acids, which have a molecular structure similar to that of steroid hormones.[32] It also contains other compounds often found in fungal materials, including polysaccharides (such as beta-glucan), coumarin,[33] mannitol, and alkaloids.[32] Sterols isolated from the mushroom include ganoderol, ganoderenic acid, ganoderiol, ganodermanontriol, lucidadiol, and ganodermadiol.[32]

A 2015 Cochrane database review found insufficient evidence to justify the use of G. lucidum as a first-line cancer treatment. It suggests that G. lucidum may have "benefit as an alternative adjunct to conventional treatment in consideration of its potential of enhancing tumour response and stimulating host immunity."[34] Existing studies do not support the use of G. lucidum for treatment of risk factors of cardiovascular disease in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus.[35]

Culinary

Because of its bitter taste, lingzhi is traditionally prepared as a hot water extract product.[22] Thinly sliced or pulverized lingzhi (either fresh or dried) is added to boiling water which is then reduced to a simmer, covered, and left for 2 hours.[36] The resulting liquid is dark and fairly bitter in taste. The red lingzhi is often more bitter than the black. The process is sometimes repeated to increase the concentration. Alternatively, it can be used as an ingredient in a formula decoction, or used to make an extract (in liquid, capsule, or powder form). The more active red forms of lingzhi are far too bitter to be consumed in a soup.[citation needed]

Lingzhi is now commercially manufactured and sold. Since the early 1970s, most lingzhi is cultivated. Lingzhi can grow on substrates such as sawdust, grain, and wood logs. After formation of the fruiting body, lingzhi is most commonly harvested, dried, ground, and processed into tablets or capsules to be directly ingested or made into tea or soup. Other lingzhi products include processed fungal mycelia or spores.[36]

Other uses

Lingzhi is also used to create mycelium bricks, mycelium furniture, and leather-like products.[citation needed]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Arora, David (1986). Mushrooms demystified: a comprehensive guide to the fleshy fungi (2nd ed.). Ten Speed Press. ISBN 978-0-89815-169-5. https://archive.org/details/mushroomsdemysti00aror_0.

- ↑ Cao, Yun; Wu, Sheng-Hua; Dai, Yu-Cheng (2012). "Species clarification of the prize medicinal Ganoderma mushroom 'Lingzhi'". Fungal Diversity 56 (1): 49–62. doi:10.1007/s13225-012-0178-5.

- ↑ Kenneth, Jones (1990). Reishi: Ancient Herb for Modern Times. Sylvan Press. p. 6.

- ↑ Dai, Y.-C. (2017). "Ganoderma lingzhi (Polyporales, Basidiomycota): the scientific binomial for the widely cultivated medicinal fungus Lingzhi". Mycological Progress 16 (11–12): 1051–1055. doi:10.1007/s11557-017-1347-4.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Zhou, Li-Wei; Cao, Yun; Wu, Sheng-Hua; Vlasák, Josef; Li, De-Wei; Li, Meng-Jie; Dai, Yu-Cheng (2015). "Global diversity of the Ganoderma lucidum complex (Ganodermataceae, Polyporales) inferred from morphology and multilocus phylogeny". Phytochemistry 114: 7–15. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.09.023. PMID 25453909.

- ↑ Karsten, PA. (1881). "Enumeratio Boletinearum et Polyporearum Fennicarum, systemate novo dispositarum" (in la). Revue Mycologique, Toulouse 3 (9): 16–19.

- ↑ Steyaert, R. L. (1961). "Note on the nomenclature of fungi and, incidentally, of Ganoderma lucidum". Taxon 10 (8): 251–252. doi:10.2307/1216350. http://www.iapt-taxon.org/historic/Congress/IBC_1964/nom_fung.pdf.

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged ed.). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-910207-5.

- ↑ Pawlik, Anna; Janusz, Grzegorz; Dębska, Iwona; Siwulski, Marek; Frąc, Magdalena; Rogalski, Jerzy (2015). "Genetic and Metabolic Intraspecific Biodiversity of Ganoderma lucidum". BioMed Research International 2015: 1–13. doi:10.1155/2015/726149. PMID 25815332.

- ↑ "Ganoderma sessile". International Mycological Association. http://www.mycobank.org/Biolomics.aspx?Table=Mycobank&MycoBankNr_=237038.

- ↑ Yajima, Yuka; Miyazaki, Minoru; Okita, Noriyasu; Hoshino, Tamotsu (2013). "Production of Ginkgo Leaf−Shaped Basidiocarps of the Lingzhi or Reishi Medicinal Mushroom Ganoderma lucidum (Higher Basidiomycetes), Containing High Levels of α- and β-D-Glucan and Ganoderic Acid A". International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms 15 (2): 175–182. doi:10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v15.i2.60.

- ↑ Hobbs, Christopher (2002). Medicinal Mushrooms: An exploration of tradition, Healing, and Culture. Botanica Press. ISBN 978-1-57067-143-2.

- ↑ National Audubon Society (1993). Field Guide to Mushrooms.

- ↑ Veena, S. S.; Pandey, Meera (2011). "Paddy Straw as a Substrate for the Cultivation of Lingzhi or Reishi Medicinal Mushroom, Ganoderma lucidum (W.Curt. :Fr.) P. Karst. in India". International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms 13 (4): 397–400. doi:10.1615/intjmedmushr.v13.i4.100. PMID 2164770.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Knechtges, David R. (1996). Wen Xuan or Selections of Refined Literature. 3. Princeton University Press. pp. 201, 211. ISBN 9780691021263. https://books.google.com/books?id=GYJi0OkKFJIC.

- ↑ "草上品". 神農本草經. http://www.theqi.com/cmed/oldbook/sn_herb/herb_3.html. "赤芝。 苦, 平, 無毒。胸中結, 益心氣, 補中, 增智慧, 不忘。久食, 輕身不老, 延年神仙。一名丹芝。 延年神仙。"

- ↑ The Divine Farmer's Materia Medica: A Translation of the Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing. Blue Poppy Enterprises. 1998. p. 17–18. ISBN 9780936185965. https://books.google.com/books?id=NjC-eTffFeQC.

- ↑ "Reishi Mushroom Benefits & Other Facts about Reishi". https://www.reishiessence.com/what-is-reishi.

- ↑ Li, Shizhen (in zh), 本草綱目, "胸中結, 益心氣, 補中, 增智慧, 不忘。久食, 輕身不老, 延年神仙。"

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Halpern, Georges M. (2007). Healing Mushrooms. Square One Publishers. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-7570-0196-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=FlrpouUh740C.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Stuart, G. A.; Smith, F. Porter (1911). Chinese Materia Medica, Pt. 1, Vegetable Kingdom. Presbyterian Mission Press. pp. 271, 274. ISBN 9780879684693. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/66623.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Smith, John; Rowan, Neil; Sullivan, Richard (2001). "Medicinal mushrooms: their therapeutic properties and current medical usage with special emphasis on cancer treatments". Cancer Research UK: 28, 31. http://sci.cancerresearchuk.org/labs/med_mush/med_mush.html.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Pregadio, Fabrizio, ed (2008). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Routledge. p. 1271. ISBN 9780203695487. https://books.google.com/books?id=MioRmEq2xHUC&pg=PP1. "Zhi 芝 numinous mushrooms; excrescences"

- ↑ Bretschneider, E. (1893). Botanicon Sinicum. Kelly & Walsh. p. 40. https://books.google.com/books?id=t_UIAAAAIAAJ.

- ↑ Groot, Johann Jacob Maria de (1892–1910). The Religious System of China. Its ancient forms, evolution, history and present aspect. Manners, customs and social institutions connected therewith. IV. Leiden: Brill Publishers. p. 307. http://classiques.uqac.ca/classiques/groot_jjm_de/religious_system_of_china/religious_system.html.

- ↑ Hu, Shiu-ying (2006). Food Plants of China. Chinese University Press. p. 268. ISBN 9789629962296. https://books.google.com/books?id=2OiYydyrsygC&pg=PA268.

- ↑ Bedini, Silvio A. (1994). The Trail of Time. Cambridge University Press. p. 113. ISBN 9780521374828. https://books.google.com/books?id=xdVkzs6iI1YC&pg=PA113.

- ↑ Schipper, Kristofer M. (1993). The Taoist Body. University of California Press. p. 174.

- ↑ "ling chih". Oxford English Dictionary (CD-ROM ed.). 2009.

- ↑ Bushell, Stephen Wootton (1904). Chinese Art. p. 148. https://books.google.com/books?id=adYMAQAAIAAJ. (Victoria and Albert Museum); This context describes the lingzhi fungus and ruyi scepter as Daoist symbols of longevity on a jade vase.

- ↑ "Names of a Selection of Asian Fungi". University of Melbourne. 18 February 1999. http://www.plantnames.unimelb.edu.au/Sorting/Fungi_Asian.html.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Paterson, R. Russell M. (2006). "Ganoderma – A therapeutic fungal biofactory". Phytochemistry 67 (18): 1985–2001. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.07.004. PMID 16905165.

- ↑ Kohguchi, Michihiro; Kunikata, Toshio; Watanabe, Hikaru; Kudo, Naoki; Shibuya, Takashi; Ishihara, Tatsuya; Iwaki, Kanso; Ikeda, Masao et al. (2014). "Immuno-potentiating Effects of the Antler-shaped Fruiting Body of (Rokkaku-Reishi)". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 68 (4): 881–887. doi:10.1271/bbb.68.881. PMID 15118318.

- ↑ Jin, Xingzhong; Ruiz Beguerie, Julieta; Sze, Daniel Man-yuen; Chan, Godfrey C.F. (2015). "Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi mushroom) for cancer treatment.". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4: CD007731. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007731.pub3. PMID 27045603.

- ↑ Klupp, Nerida L.; Chang, Dennis; Hawke, Fiona; Kiat, Hosen; Cao, Huijuan; Grant, Suzanne J.; Bensoussan, Alan (2015). "Ganoderma lucidum mushroom for the treatment of cardiovascular risk factors". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD007259. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007259.pub2. PMID 25686270.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Wachtel-Galor, Sissi; Yuen, John; Buswell, John A.; Benzie, Iris F. F. (2011). "Ganoderma lucidum (Lingzhi or Reishi): A Medicinal Mushroom". in Benzie, Iris F. F.; Wachtel-Galor, Sissi. Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-4398-0713-2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92757/.

Wikidata ☰ Q271098 entry