Medicine:Injury

| Injury | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cat scratches on an arm, a minor traumatic puncture wound to the skin | |

| Complications | Infection, shock, hemorrhaging, organ failure |

| Types | Traumatic, burn, toxic, overuse |

An injury is any physiological damage to living tissue[1] caused by immediate physical stress. An injury can occur intentionally or unintentionally and may be caused by blunt trauma, penetrating trauma, burning, toxic exposure, asphyxiation, or overexertion. Injuries can occur in any part of the body, and different symptoms are associated with different injuries.

Treatment of a major injury is typically carried out by a health professional and varies greatly depending on the nature of the injury. Traffic collisions are the most common cause of accidental injury and injury-related death among humans. Injuries are distinct from chronic conditions, psychological trauma, infections, or medical procedures, though injury can be a contributing factor to any of these.

Several major health organizations have established systems for the classification and description of human injuries.

Occurrence

Injuries may be intentional or unintentional. Intentional injuries may be acts of violence against others or self-harm against one's own person. Accidental injuries may be unforeseeable or they may be caused by negligence The most common types of unintentional injuries in order are traffic accidents, falls, drowning, burns, and accidental poisoning. Certain types of injuries are more common in developed countries or developing countries. Traffic injuries are more likely to kill pedestrians than drivers in developing countries. Scalding burns are more common in developed countries, while open-flame injuries are more common in developing countries.[2]

As of 2021, approximately 4.4 million people are killed due to injuries each year worldwide, constituting nearly 8% of all deaths. 3.16 million of these injuries are unintentional and 1.25 million are intentional. Traffic accidents are the most common form of deadly injury, causing about one-third of injury-related deaths. One-sixth are caused by suicide, and one-tenth are caused by homicide. Tens of millions of individuals require medical treatment for nonfatal injuries each year, and injuries are responsible for about 10% of all years lived with disability. Men are twice as likely to be killed through injury than women.[3] In 2013, 367,000 children under the age of five died from injuries, down from 766,000 in 1990.[4]

Classification systems

The World Health Organization (WHO) developed the International Classification of External Causes of Injury (ICECI). Under this system, injuries are classified by mechanism of injury, objects/substances producing injury, place of occurrence, activity when injured, the role of human intent, and additional modules. These codes allow the identification of distributions of injuries in specific populations and case identification for more detailed research on causes and preventive efforts.[5]

The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics developed the Occupational Injury and Illness Classification System (OIICS). Under this system injuries are classified by nature, part of body affected, source and secondary source, and event or exposure. The OIICS was first published in 1992 and has been updated several times since.[6] The Orchard Sports Injury and Illness Classification System (OSIICS), previously OSICS, is used to classify injuries to enable research into specific sports injuries.[7][8]

The injury severity score (ISS) is a medical score to assess trauma severity.[9][10] It correlates with mortality, morbidity, and hospitalization time after trauma. It is used to define the term major trauma (polytrauma), recognized when the ISS is greater than 15.[10] The AIS Committee of the Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine designed and updates the scale.

Mechanisms

Trauma

Traumatic injury is caused by an external object making forceful contact with the body, resulting in a wound. Major trauma is a severe traumatic injury that has the potential to cause disability or death. Serious traumatic injury most often occurs as a result of traffic collisions.[11] Traumatic injury is the leading cause of death in people under the age of 45.[12]

Blunt trauma injuries are caused by the forceful impact of an external object. Injuries from blunt trauma may cause internal bleeding and bruising from ruptured capillaries beneath the skin, abrasion from scraping against the superficial epidermis, lacerated tears on the skin or internal organs, or bone fractures. Crush injuries are a severe form of blunt trauma damage that apply large force to a large area over a longer period of time.[11] Penetrating trauma injuries are caused by external objects entering the tissue of the body through the skin. Low-velocity penetration injuries are caused by sharp objects, such as stab wounds, while high-velocity penetration injuries are caused by ballistic projectiles, such as gunshot wounds or injuries caused by shell fragments.[13] Perforated injuries result in an entry wound and an exit wound, while puncture wounds result only in an entry wound. Puncture injuries result in a cavity in the tissue.[14]

Burns

Burn injury is caused by contact with extreme temperature, chemicals, or radiation. The effects of burns vary depending on the depth and size. Superficial or first-degree burns only affect the epidermis, causing pain for a short period of time. Superficial partial-thickness burns cause weeping blisters and require dressing. Deep partial-thickness burns are dry and less painful due to the burning away of the skin and require surgery. Full-thickness or third-degree burns affect the entire dermis and is susceptible to infection. Fourth-degree burns reach deep tissues such as muscles and bones, causing loss of the affected area.[15]

Thermal burns are the most common type of burn, caused by contact with excessive heat, including contact with flame, contact with hot surfaces, or scalding burns caused by contact with hot water or steam. Frostbite is a type of burn caused by contact with excessive cold, causing cellular injury and deep tissue damage through the crystallization of water in the tissue. Friction burns are caused by friction with external objects, resulting in a burn and abrasion.[15] Radiation burns are caused by exposure to ionizing radiation. Most radiation burns are sunburns caused by ultraviolet radiation or high exposure to radiation through medical treatments such as repeated radiography or radiation therapy.[16]

Electrical burns are caused by contact with electricity as it enters and passes through the body. They are often deeper than other burns, affecting lower tissues as electricity penetrates the skin, and the full extent of electrical burns are often obscured. They will also cause extensive destruction of tissue at the entry and exit points. Electrical injuries in the home are often minor, while high tension power cables cause serious electrical injuries in the workplace. Lightning strikes can also cause severe electrical injuries. Fatal electrical injuries are often caused by tetanic spasm inducing respiratory arrest or interference with the heart causing cardiac arrest.[17]

Chemical burns are caused by contact with corrosive substances such as acid or alkali. Chemical burns are rarer than most other burns, though there are many chemicals that can damage tissue. The most common chemical-related injuries are those caused by carbon monoxide, ammonia, chlorine, hydrochloric acid, and sulfuric acid. Some chemical weapons induce chemical burns, such as white phosphorus. Most chemical burns are treated with extensive application of water to remove the chemical contaminant, though some burn-inducing chemicals react with water to create more severe injuries.[18] The ingestion of corrosive substances can cause chemical burns to the larynx and stomach.[19]

Other mechanisms

Toxic injury is caused by the ingestion, inhalation, injection, or absorption of a toxin. This may occur through an interaction caused by a drug or the ingestion of a poison. Different toxins may cause different types of injuries, and many will cause injury to specific organs.[20] Toxins in gases, dusts, aerosols, and smoke can be inhaled, potentially causing respiratory failure. Respiratory toxins can be released by structural fires, industrial accidents, domestic mishaps, or through chemical weapons. Some toxicants may affect other parts of the body after inhalation, such as carbon monoxide.[21]

Asphyxia causes injury to the body from a lack of oxygen. It can be caused by drowning, inhalation of certain substances, strangulation, blockage of the airway, traumatic injury to the airway, apnea, and other means. The most immediate injury caused by asphyxia is hypoxia, which can in turn cause acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome as well as damage to the circulatory system. The most severe injury associated with asphyxiation is cerebral hypoxia and ischemia, in which the brain receives insufficient oxygen or blood, resulting in neurological damage or death. Specific injuries are associated with water inhalation, including alveolar collapse, atelectasis, intrapulmonary shunting, and ventilation perfusion mismatch.[22] Simple asphyxia is caused by a lack of external oxygen supply. Systemic asphyxia is caused by exposure to a compound that prevents oxygen from being transported or used by the body. This can be caused by azides, carbon monoxide, cyanide, smoke inhalation, hydrogen sulfide, methemoglobinemia-inducing substances, opioids, or other systemic asphyxiants. Ventilation and oxygenation are necessary for treatment of asphyxiation, and some asphyxiants can be treated with antidotes.[23]

Injuries of overuse or overexertion can occur when the body is strained through use, affecting the bones, muscles, ligaments, or tendons. Sports injuries are often overuse injuries such as tendinopathy.[24] Over-extension of the ligaments and tendons can result in sprains and strains, respectively.[25] Repetitive sedentary behaviors such as extended use of a computer or a physically repetitive occupation may cause a repetitive strain injury.[26] Extended use of brightly lit screens may also cause eye strain.[27]

Locations

Abdomen

Abdominal trauma includes injuries to the stomach, intestines, liver, pancreas, kidneys, gallbladder, and spleen. Abdominal injuries are typically caused by traffic accidents, assaults, falls, and work-related injuries, and physical examination is often unreliable in diagnosing blunt abdominal trauma. Splenic injury can cause low blood volume or blood in the peritoneal cavity. The treatment and prognosis of splenic injuries are dependent on cardiovascular stability.[28] The gallbladder is rarely injured in blunt trauma, occurring in about 2% of blunt abdominal trauma cases. Injuries to the gallbladder are typically associated with injuries to other abdominal organs.[29] The intestines are susceptible to injury following blunt abdominal trauma.[30] The kidneys are protected by other structures in the abdomen, and most injuries to the kidney are a result of blunt trauma.[31] Kidney injuries typically cause blood in the urine.[32]

Due to its location in the body, pancreatic injury is relatively uncommon but more difficult to diagnose. Most injuries to the pancreas are caused by penetrative trauma, such as gunshot wounds and stab wounds. Pancreatic injuries occur in under 5% of blunt abdominal trauma cases. The severity of pancreatic injury depends primarily on the amount of harm caused to the pancreatic duct.[33] The stomach is also well protected from injury due to its heavy layering, its extensive blood supply, and its position relative to the rib cage. As with pancreatic injuries, most traumatic stomach injuries are caused by penetrative trauma, and most civilian weapons do not cause long-term tissue damage to the stomach. Blunt trauma injuries to the stomach are typically caused by traffic accidents.[34] Ingestion of corrosive substances can cause chemical burns to the stomach.[19] Liver injury is the most common type of organ damage in cases of abdominal trauma.[35] The liver's size and location in the body makes injury relatively common compared to other abdominal organs, and blunt trauma injury to the liver is typically treated with nonoperative management.[36] Liver injuries are rarely serious, though most injuries to the liver are concomitant with other injuries, particularly to the spleen, ribs, pelvis, or spinal cord.[35] The liver is also susceptible to toxic injury, with overdose of paracetamol being a common cause of liver failure.[37]

Face

Facial trauma may affect the eyes, nose, ears, or mouth. Nasal trauma is a common injury and the most common type of facial injury.[38] Oral injuries are typically caused by traffic accidents or alcohol-related violence, though falls are a more common cause in young children. The primary concerns regarding oral injuries are that the airway is clear and that there are no concurrent injuries to other parts of the head or neck. Oral injuries may occur in the soft tissue of the face, the hard tissue of the mandible, or as dental trauma.[39]

The ear is susceptible to trauma in head injuries due to its prominent location and exposed structure. Ear injuries may be internal or external. Injuries of the external ear are typically lacerations of the cartilage or the formation of a hematoma. Injuries of the middle and internal ear may include a perforated eardrum or trauma caused by extreme pressure changes. The ear is also highly sensitive to blast injury. The bones of the ear are connected to facial nerves, and ear injuries can cause paralysis of the face. Trauma to the ear can cause hearing loss.[40]

Eye injuries often take place in the cornea, and they have the potential to permanently damage vision. Corneal abrasions are a common injury caused by contact with foreign objects. The eye can also be injured by a foreign object remaining in the cornea. Radiation damage can be caused by exposure to excessive light, often caused by welding without eye protection or being exposed to excessive ultraviolet radiation, such as sunlight. Exposure to corrosive chemicals can permanently damage the eyes, causing blindness if not sufficiently irrigated. The eye is protected from most blunt injuries by the infraorbital margin, but in some cases blunt force may cause an eye to hemorrhage or tear.[41] Overuse of the eyes can cause eye strain, particularly when looking at brightly lit screens for an extended period.[27]

Heart

Cardiac injuries affect the heart and blood vessels. Blunt cardiac injury in a common injury caused by blunt trauma to the heart. It can be difficult to diagnose, and it can have many effects on the heart, including contusions, ruptures, acute valvular disorders, arrhythmia, or heart failure.[42] Penetrative trauma to the heart is typically caused by stab wounds or gunshot wounds. Accidental cardiac penetration can also occur in rare cases from a fractured sternum or rib. Stab wounds to the heart are typically survivable with medical attention, though gunshot wounds to the heart are not. The right ventricle is most susceptible to injury due to its prominent location. The two primary consequences of traumatic injury to the heart are severe hemorrhaging and fluid buildup around the heart.[43]

Musculoskeletal

Musculoskeletal injuries affect the skeleton and the muscular system. Soft tissue injuries affect the skeletal muscles, ligaments, and tendons. Ligament and tendon injuries account for half of all musculoskeletal injuries. Ligament sprains and tendon strains are common injuries that do not require intervention, but the healing process is slow. Physical therapy can be used to assist reconstruction and use of injured ligaments and tendons. Torn ligaments or tendons typically require surgery.[25] Skeletal muscles are abundant in the body and commonly injured when engaging in athletic activity. Muscle injuries trigger an inflammatory response to facilitate healing. Blunt trauma to the muscles can cause contusions and hematomas. Excessive tensile strength can overstretch a muscle, causing a strain. Strains may present with torn muscle fibers, hemorrhaging, or fluid in the muscles. Severe muscle injuries in which a tear extends across the muscle can cause total loss of function. Penetrative trauma can cause laceration to muscles, which may take an extended time to heal. Unlike contusions and strains, lacerations are uncommon in sports injuries.[44]

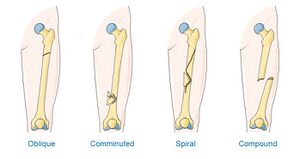

Traumatic injury may cause various bone fractures depending on the amount of force, direction of the force, and width of the area affected. Pathologic fractures occur when a previous condition weakens the bone until it can be easily fractured. Stress fractures occur when the bone is overused or suffers under excessive or traumatic pressure, often during athletic activity. Hematomas occur immediately following a bone fracture, and the healing process often takes from six weeks to three months to complete, though continued use of the fractured bone will prevent healing.[45] Articular cartilage damage may also affect function of the skeletal system, and it can cause posttraumatic osteoarthritis. Unlike most bodily structures, cartilage cannot be healed once it is damaged.[46]

Nervous system

Injuries to the nervous system include brain injury, spinal cord injury, and nerve injury. Trauma to the brain causes traumatic brain injury (TBI), causing "long-term physical, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive consequences". Mild TBI, including concussion, often occurs during athletic activity, military service, or as a result of untreated epilepsy, and its effects are typically short-term. More severe injuries to the brain cause moderate TBI, which may cause confusion or lethargy, or severe TBI, which may result in a coma or a secondary brain injury. TBI is a leading cause of mortality.[47] Approximately half of all trauma-related deaths involve TBI.[12] Non-traumatic injuries to the brain cause acquired brain injury (ABI). This can be caused by stroke, a brain tumor, poison, infection, cerebral hypoxia, drug use, or the secondary effect of a TBI.[48]

Injury to the spinal cord is not immediately terminal, but it is associated with concomitant injuries, lifelong medical complications, and reduction in life expectancy. It may result in complications in several major organ systems and a significant reduction in mobility or paralysis. Spinal shock causes temporary paralysis and loss of reflexes.[49] Unlike most other injuries, damage to the peripheral nerves is not healed through cellular proliferation. Following nerve injury, the nerves undergo degeneration before regenerating, and other pathways can be strengthened or reprogrammed to make up for lost function. The most common form of peripheral nerve injury is stretching, due to their inherent elasticity. Nerve injuries may also be caused by laceration or compression.[50]

Pelvis

Injuries to the pelvic area include injuries to the bladder, rectum, colon, and reproductive organs. Traumatic injury to the bladder is rare and often occurs with other injuries to the abdomen and pelvis. The bladder is protected by the peritoneum, and most cases of bladder injury are concurrent with a fracture of the pelvis. Bladder trauma typically causes hematuria, or blood in the urine. Ingestion of alcohol may cause distension of the bladder, increasing the risk of injury. A catheter may be used to extract blood from the bladder in the case of hemorrhaging, though injuries that break the peritoneum typically require surgery.[51] The colon is rarely injured by blunt trauma, with most cases occurring from penetrative trauma through the abdomen. Rectal injury is less common than injury to the colon, though the rectum is more susceptible to injury following blunt force trauma to the pelvis.[52]

Injuries to the male reproductive system are rarely fatal and typically treatable through grafts and reconstruction. The elastic nature of the scrotum makes it resistant to injury, accounting for 1% of traumatic injuries. Trauma to the scrotum may cause damage to the testis or the spermatic cord. Trauma to the penis can cause penile fracture, typically as a result of vigorous intercourse.[53] Injuries to the female reproductive system are often a result of pregnancy and childbirth or sexual activity. They are rarely fatal, but they can produce a variety of complications, such as chronic discomfort, dyspareunia, infertility, or the formation of fistulas. Age can greatly affect the nature of genital injuries in women due to changes in hormone composition. Childbirth is the most common cause of genital injury to women of reproductive age. Many cultures practice female genital mutilation, which is estimated to affect over 125 million women and girls worldwide as of 2018.[54] Tears and abrasions to the vagina are common during sexual intercourse, and these may be exacerbated in instances of non-consensual sexual activity.[55]

Respiratory tract

Injuries to the respiratory tract affect the lungs, diaphragm, trachea, bronchus, pharynx, or larynx. Tracheobronchial injuries are rare and often associated with other injuries. Bronchoscopy is necessary for an accurate diagnosis of tracheobronchial injury.[56] The neck, including the pharynx and larynx, is highly vulnerable to injury due to its complex, compacted anatomy. Injuries to this area can cause airway obstruction.[57] Ingestion of corrosive chemicals can cause chemical burns to the larynx.[19] Inhalation of toxic materials can also cause serious injury to the respiratory tract.[21]

Severe trauma to the chest can cause damage to the lungs, including pulmonary contusions, accumulation of blood, or a collapsed lung. The inflammation response to a lung injury can cause acute respiratory distress syndrome. Injuries to the lungs may cause symptoms ranging from shortness of breath to terminal respiratory failure. Injuries to the lungs are often fatal, and survivors often have a reduced quality of life.[58] Injuries to the diaphragm are uncommon and rarely serious, but blunt trauma to the diaphragm can result in the formation of a hernia over time.[59] Injuries to the diaphragm may present in many ways, including abnormal blood pressure, cardiac arrest, gastroinetestinal obstruction, and respiratory insufficiency. Injuries to the diaphragm are often associated with other injuries in the chest or abdomen, and its position between two major cavities of the human body may complicate diagnosis.[60]

Skin

Most injuries to the skin are minor and do not require specialist treatment. Lacerations of the skin are typically repaired with sutures, staples, or adhesives. The skin is susceptible to burns, and burns to the skin often cause blistering. Abrasive trauma scrapes or rubs off the skin, and severe abrasions require skin grafting to repair. Skin tears involve the removal of the epidermis or dermis through friction or shearing forces, often in vulnerable populations such as the elderly. Skin injuries are potentially complicated by foreign bodies such as glass, metal, or dirt that entered the wound, and skin wounds often require cleaning.[61]

Treatment

Much of medical practice is dedicated to the treatment of injuries. Traumatology is the study of traumatic injuries and injury repair. Certain injuries may be treated by specialists. Serious injuries sometimes require trauma surgery. Following serious injuries, physical therapy and occupational therapy are sometimes used for rehabilitation. Medication is commonly used to treat injuries.

Emergency medicine during major trauma prioritizes the immediate consideration of life-threatening injuries that can be quickly addressed. The airway is evaluated, clearing bodily fluids with suctioning or creating an artificial airway if necessary. Breathing is evaluated by evaluating motion of the chest wall and checking for blood or air in the pleural cavity. Circulation is evaluated to resuscitate the patient, including the application of intravenous therapy. Disability is evaluated by checking for responsiveness and reflexes. Exposure is then used to examine the patient for external injury. Following immediate life-saving procedures, a CT scan is used for a more thorough diagnosis. Further resuscitation may be required, including ongoing blood transfusion, mechanical ventilation and nutritional support.[12]

Pain management is another aspect of injury treatment. Pain serves as an indicator to determine the nature and severity of an injury, but it can also worsen an injury, reduce mobility, and affect quality of life. Analgesic drugs are used to reduce the pain associated with injuries, depending on the person's age, the severity of the injury, and previous medical conditions that may affect pain relief. NSAIDs such as aspirin and ibuprofen are commonly used for acute pain. Opioid medications such as fentanyl, methadone, and morphine are used to treat severe pain in major trauma, but their use is limited due to associated long-term risks such as addiction.[62] In addition to medications, non-pharmacological interventions can be beneficial when treating pain. The mnemonic TWEED SASH summarises some of these:[63]

| Non-Pharmacological Analgesic Strategies | |

|---|---|

| Psychological Interventions | |

| T | Therapeutic Touch (e.g. hand-holding) |

| W | Warn about painful interventions |

| E | Explain what is, or is about to, happen |

| E | Eye contact |

| D | Defend (patient) dignity |

| Physical Interventions | |

| S | Stabilise fractures |

| A | Apply dressings to cover burns |

| S | Soft surface (avoid rigid spinal boards or stretchers) |

| H | Hypothermia avoidance |

Complications

Complications may arise as a result of certain injuries, increasing the recovery time, further exasperating the symptoms, or potentially causing death. The extent of the injury and the age of the injured person may contribute to the likelihood of complications. Infection of wounds is a common complication in traumatic injury, resulting in diagnoses such as pneumonia or sepsis.[64] Wound infection prevents the healing process from taking place and can cause further damage to the body. A majority of wounds are contaminated with microbes from other parts of the body, and infection takes place when the immune system is unable to address this contamination. The surgical removing of devitalized tissue and the use of topical antimicrobial agents can prevent infection.[65]

Hemorrhaging of blood is a common result of injuries, and it can cause several complications. Pooling of blood under the skin can cause a hematoma, particularly after blunt trauma or the suture of a laceration. Hematomas are susceptible to infection and are typically treated compression, though surgery is necessary in severe cases.[66] Excessive blood loss can cause hypovolemic shock in which cellular oxygenation can no longer take place. This can cause tachycardia, hypotension, coma, or organ failure. Fluid replacement is often necessary to treat blood loss.[67] Other complications of injuries include cavitation, development of fistulas, and organ failure.

Social and psychological aspects

Injuries often cause psychological harm in addition to physical harm. Traumatic injuries are associated with psychological trauma and distress, and some victims of traumatic injuries will display symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder during and after the recovery of the injury. The specific symptoms and their triggers vary depending on the nature of the injury.[68] Body image and self-esteem can also be affected by injury. Injuries that cause permanent disabilities, such as spinal cord injuries, can have severe effects on self-esteem.[69][70] Disfiguring injuries can negatively affect body image, leading to a lower quality of life. Burn injuries in particular can cause dramatic changes in a person's appearance that may negatively affect body image.[71][72][73]

Severe injury can also cause social harm. Disfiguring injuries may also result in stigma due to scarring or other changes in appearance.[74][75] Certain injuries may necessitate a change in occupation or prevent employment entirely. Leisure activities are similarly limited, and athletic activities in particular may be impossible following severe injury. In some cases, the effects of injury may strain personal relationships, such as marriages.[76] Psychological and social variables have been found to affect the likelihood of injuries among athletes. Increased life stress can cause an increase in the likelihood of athletic injury, while social support can decrease the likelihood of injury.[77][78] Social support also assists in the recovery process after athletic injuries occur.[79]

See also

References

- ↑ Concise Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2002. p. 729. ISBN 0-19-860572-2.

- ↑ de Ramirez, Sarah Stewart; Hyder, Adnan A.; Herbert, Hadley K.; Stevens, Kent (2012). "Unintentional injuries: magnitude, prevention, and control". Annual Review of Public Health 33: 175–191. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124558. ISSN 1545-2093. PMID 22224893.

- ↑ "Injuries and violence" (in en). 2021-03-19. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/injuries-and-violence.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMID 25530442.

- ↑ "International Classification of External Causes of Injury (ICECI)". World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/adaptations/iceci/en/.

- ↑ "Occupational Injury and Illness Classification System". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/wisards/oiics/.

- ↑ Rae, K; Orchard, J (May 2007). "The Orchard Sports Injury Classification System (OSICS) version 10". Clin J Sport Med 17 (3): 201–04. doi:10.1097/jsm.0b013e318059b536. PMID 17513912. http://raco.cat/index.php/Apunts/article/view/119817.

- ↑ Orchard, JW; Meeuwisse, W; Derman, W; Hägglund, M; Soligard, T; Schwellnus, M; Bahr, R (April 2020). "Sport Medicine Diagnostic Coding System (SMDCS) and the Orchard Sports Injury and Illness Classification System (OSIICS): revised 2020 consensus versions.". British Journal of Sports Medicine 54 (7): 397–401. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-101921. PMID 32114487.

- ↑ "The Injury Severity Score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care". The Journal of Trauma 14 (3): 187–96. 1974. doi:10.1097/00005373-197403000-00001. PMID 4814394.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Copes, W.S.; H.R. Champion; W.J. Sacco; M.M. Lawnick; S.L. Keast; L.W. Bain (1988). "The Injury Severity Score revisited". The Journal of Trauma 28 (1): 69–77. doi:10.1097/00005373-198801000-00010. PMID 3123707.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Simon, Leslie V.; Lopez, Richard A.; King, Kevin C. (May 1, 2022). "Blunt Force Trauma". StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing). PMID 29262209. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470338/. Retrieved 2022-07-17.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Maerz, Linda L.; Davis, Kimberly A.; Rosenbaum, Stanley H. (2009). "Trauma". International Anesthesiology Clinics 47 (1): 25–36. doi:10.1097/AIA.0b013e3181950030. ISSN 1537-1913. PMID 19131750. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19131750/.

- ↑ Alao, Titilola; Waseem, Muhammad (November 7, 2021). "Penetrating Head Trauma". StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing). PMID 29083824. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459254/. Retrieved 2022-07-17.

- ↑ Lotfollahzadeh, Saran; Burns, Bracken (May 4, 2022). "Penetrating Abdominal Trauma". StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing). PMID 29083811. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459123/. Retrieved 2022-07-17.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Jeschke, Marc G.; van Baar, Margriet E.; Choudhry, Mashkoor A.; Chung, Kevin K.; Gibran, Nicole S.; Logsetty, Sarvesh (2020-02-13). "Burn injury". Nature Reviews. Disease Primers 6 (1): 11. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0145-5. ISSN 2056-676X. PMID 32054846.

- ↑ Waghmare, Chaitali Manohar (2013). "Radiation burn--from mechanism to management". Burns: Journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries 39 (2): 212–219. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2012.09.012. ISSN 1879-1409. PMID 23092699. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23092699/.

- ↑ Docking, P. (1999). "Electrical burn injuries". Accident and Emergency Nursing 7 (2): 70–76. doi:10.1016/s0965-2302(99)80024-1. ISSN 0965-2302. PMID 10578716. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10578716/.

- ↑ Friedstat, Jonathan; Brown, David A.; Levi, Benjamin (2017). "Chemical, Electrical, and Radiation Injuries". Clinics in Plastic Surgery 44 (3): 657–669. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2017.02.021. ISSN 1558-0504. PMID 28576255.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Chirica, Mircea; Bonavina, Luigi; Kelly, Michael D.; Sarfati, Emile; Cattan, Pierre (2017-05-20). "Caustic ingestion". Lancet 389 (10083): 2041–2052. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30313-0. ISSN 1474-547X. PMID 28045663. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28045663/.

- ↑ Dear, James W. (2014-01-01), Marshall, William J.; Lapsley, Marta; Day, Andrew P. et al., eds., "CHAPTER 40 - Poisoning" (in en), Clinical Biochemistry: Metabolic and Clinical Aspects (Third Edition) (Churchill Livingstone): pp. 787–807, ISBN 978-0-7020-5140-1, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780702051401000407, retrieved 2022-07-17

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Chen, Tze-Ming Benson; Malli, Harjoth; Maslove, David M.; Wang, Helena; Kuschner, Ware G. (2013). "Toxic inhalational exposures". Journal of Intensive Care Medicine 28 (6): 323–333. doi:10.1177/0885066611432541. ISSN 1525-1489. PMID 22232204. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22232204/.

- ↑ Ibsen, Laura M.; Koch, Thomas (2002). "Submersion and asphyxial injury". Critical Care Medicine 30 (11 Suppl): S402–408. doi:10.1097/00003246-200211001-00004. ISSN 0090-3493. PMID 12528781. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12528781/.

- ↑ Borron, Stephen W.; Bebarta, Vikhyat S. (2015). "Asphyxiants". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 33 (1): 89–115. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2014.09.014. ISSN 1558-0539. PMID 25455664. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25455664/.

- ↑ Aicale, R.; Tarantino, D.; Maffulli, N. (2018-12-05). "Overuse injuries in sport: a comprehensive overview". Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 13 (1): 309. doi:10.1186/s13018-018-1017-5. ISSN 1749-799X. PMID 30518382.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Leong, Natalie L.; Kator, Jamie L.; Clemens, Thomas L.; James, Aaron; Enamoto-Iwamoto, Motomi; Jiang, Jie (2020). "Tendon and Ligament Healing and Current Approaches to Tendon and Ligament Regeneration". Journal of Orthopaedic Research 38 (1): 7–12. doi:10.1002/jor.24475. ISSN 1554-527X. PMID 31529731.

- ↑ Shuttleworth, Ann (2004). "Repetitive strain injury: causes, treatment and prevention". Nursing Times 100 (8): 26–27. ISSN 0954-7762. PMID 15027222. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15027222/.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Coles-Brennan, Chantal; Sulley, Anna; Young, Graeme (2019). "Management of digital eye strain". Clinical & Experimental Optometry 102 (1): 18–29. doi:10.1111/cxo.12798. ISSN 1444-0938. PMID 29797453. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29797453/.

- ↑ Williamson, Jml (2015). "Splenic injury: diagnosis and management". British Journal of Hospital Medicine 76 (4): 204–206, 227–-9. doi:10.12968/hmed.2015.76.4.204. ISSN 1750-8460. PMID 25853350. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25853350/.

- ↑ Jaggard, Matthew K. J.; Johal, Navroop S.; Choudhry, Muhammad (2011). "Blunt abdominal trauma resulting in gallbladder injury: a review with emphasis on pediatrics". The Journal of Trauma 70 (4): 1005–1010. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181fcfa17. ISSN 1529-8809. PMID 21610404. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21610404/.

- ↑ Munns, J.; Richardson, M.; Hewett, P. (1995). "A review of intestinal injury from blunt abdominal trauma". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery 65 (12): 857–860. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.1995.tb00576.x. ISSN 0004-8682. PMID 8611108. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8611108/.

- ↑ Viola, Tracey A. (2013). "Closed kidney injury". Clinics in Sports Medicine 32 (2): 219–227. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2012.12.002. ISSN 1556-228X. PMID 23522503. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23522503/.

- ↑ Petrone, Patrizio; Perez-Calvo, Javier; Brathwaite, Collin E. M.; Islam, Shahidul; Joseph, D'Andrea K. (2020). "Traumatic kidney injuries: A systematic review and meta-analysis". International Journal of Surgery (London, England) 74: 13–21. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.12.013. ISSN 1743-9159. PMID 31870753.

- ↑ Ahmed, Nasim; Vernick, Jerome J. (2009). "Pancreatic injury". Southern Medical Journal 102 (12): 1253–1256. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181c0dfca. ISSN 1541-8243. PMID 20016434. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20016434/.

- ↑ Durham, R. (1990). "Management of gastric injuries". The Surgical Clinics of North America 70 (3): 517–527. doi:10.1016/s0039-6109(16)45127-3. ISSN 0039-6109. PMID 2190331. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2190331/.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Casiero, Deena C. (2013). "Closed liver injury". Clinics in Sports Medicine 32 (2): 229–238. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2012.12.007. ISSN 1556-228X. PMID 23522504. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23522504/.

- ↑ Stracieri, Luis Donizeti da Silva; Scarpelini, Sandro (2006). "Hepatic injury". Acta Cirurgica Brasileira 21 Suppl 1: 85–88. doi:10.1590/s0102-86502006000700019. ISSN 0102-8650. PMID 17013521.

- ↑ Fisher, Kurt; Vuppalanchi, Raj; Saxena, Romil (2015). "Drug-Induced Liver Injury". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 139 (7): 876–887. doi:10.5858/arpa.2014-0214-RA. ISSN 1543-2165. PMID 26125428. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26125428/.

- ↑ Hope, N; Young, K; Mclaughlin, K; Smyth, C (2021). "Nasal Trauma: Who Nose what happens to the non-manipulated?". The Ulster Medical Journal 90 (1): 10–12. ISSN 0041-6193. PMID 33642627.

- ↑ Bringhurst, C.; Herr, R. D.; Aldous, J. A. (1993). "Oral trauma in the emergency department". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 11 (5): 486–490. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(93)90091-o. ISSN 0735-6757. PMID 8103330. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8103330/.

- ↑ Ballivet de Régloix, Stanislas; Crambert, A.; Maurin, O.; Lisan, Q.; Marty, S.; Pons, Y. (2017). "Blast injury of the ear by massive explosion: a review of 41 cases". Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 163 (5): 333–338. doi:10.1136/jramc-2016-000733. ISSN 0035-8665. PMID 28209807. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28209807/.

- ↑ Khaw, P. T.; Shah, P.; Elkington, A. R. (2004-01-03). "Injury to the eye". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 328 (7430): 36–38. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7430.36. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 14703545.

- ↑ Marcolini, Evie G.; Keegan, Joshua (2015). "Blunt Cardiac Injury". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 33 (3): 519–527. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2015.04.003. ISSN 1558-0539. PMID 26226863. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26226863/.

- ↑ Ivatury, R. R.; Rohman, M. (1989). "The injured heart". The Surgical Clinics of North America 69 (1): 93–110. doi:10.1016/s0039-6109(16)44738-9. ISSN 0039-6109. PMID 2643187. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2643187/.

- ↑ Souza, Jaqueline de; Gottfried, Carmem (2013). "Muscle injury: review of experimental models". Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 23 (6): 1253–1260. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2013.07.009. ISSN 1873-5711. PMID 24011855. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24011855/.

- ↑ Macmahon, Peter; Eustace, Stephen J. (2006). "General principles". Seminars in Musculoskeletal Radiology 10 (4): 243–248. doi:10.1055/s-2007-971995. ISSN 1089-7860. PMID 17387638. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17387638/.

- ↑ Borrelli, Joseph; Olson, Steven A.; Godbout, Charles; Schemitsch, Emil H.; Stannard, James P.; Giannoudis, Peter V. (2019). "Understanding Articular Cartilage Injury and Potential Treatments". Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 33 Suppl 6 (3): S6–S12. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000001472. ISSN 1531-2291. PMID 31083142.

- ↑ Mckee, Ann C.; Daneshvar, Daniel H. (2015). "The neuropathology of traumatic brain injury". Handbook of Clinical Neurology 127: 45–66. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52892-6.00004-0. ISBN 9780444528926. ISSN 0072-9752. PMID 25702209.

- ↑ "What is Acquired Brain Injury (ABI)" (in en-AU). 2022-07-12. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/abios/asp/what_is_abi.

- ↑ Eckert, Matthew J.; Martin, Matthew J. (2002). "Trauma: Spinal Cord Injury". The Surgical Clinics of North America 97 (5): 1031–1045. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2017.06.008. ISSN 1558-3171. PMID 28958356. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28958356/.

- ↑ Burnett, Mark G.; Zager, Eric L. (2004-05-15). "Pathophysiology of peripheral nerve injury: a brief review". Neurosurgical Focus 16 (5): E1. doi:10.3171/foc.2004.16.5.2. ISSN 1092-0684. PMID 15174821.

- ↑ Mahat, Yashmi; Leong, Joon Yau; Chung, Paul H. (2019). "A contemporary review of adult bladder trauma". Journal of Injury & Violence Research 11 (2): 101–106. doi:10.5249/jivr.v11i2.1069. ISSN 2008-4072. PMID 30979861.

- ↑ Falcone, R. E.; Carey, L. C. (1988). "Colorectal trauma". The Surgical Clinics of North America 68 (6): 1307–1318. doi:10.1016/s0039-6109(16)44688-8. ISSN 0039-6109. PMID 3057661. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3057661/.

- ↑ Furr, James; Culkin, Daniel (2017). "Injury to the male external genitalia: a comprehensive review". International Urology and Nephrology 49 (4): 553–561. doi:10.1007/s11255-017-1526-x. ISSN 1573-2584. PMID 28181114. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28181114/.

- ↑ Lopez, Heather N.; Focseneanu, Mariel A.; Merritt, Diane F. (2018). "Genital injuries acute evaluation and management". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 48: 28–39. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.09.009. ISSN 1532-1932. PMID 29117923. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29117923/.

- ↑ Anderson, Jocelyn C.; Sheridan, Daniel J. (2012). "Female genital injury following consensual and nonconsensual sex: state of the science". Journal of Emergency Nursing 38 (6): 518–522. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2010.10.014. ISSN 1527-2966. PMID 21514642. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21514642/.

- ↑ Johnson, Scott B. (2008). "Tracheobronchial injury". Seminars in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 20 (1): 52–57. doi:10.1053/j.semtcvs.2007.09.001. ISSN 1043-0679. PMID 18420127. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18420127/.

- ↑ Berget, J.; Tonglet, M.; Ransy, P.; Gillet, A.; D'Orio, V.; Moreau, P.; Ghuysen, A.; Demez, P. (2016). "Direct and indirect injuries of the pharynx and larynx". B-ENT Suppl 26 (2): 59–68. ISSN 1781-782X. PMID 29558577. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29558577/.

- ↑ Dogrul, Bekir Nihat; Kiliccalan, Ibrahim; Asci, Ekrem Samet; Peker, Selim Can (2020). "Blunt trauma related chest wall and pulmonary injuries: An overview". Chinese Journal of Traumatology = Zhonghua Chuang Shang Za Zhi 23 (3): 125–138. doi:10.1016/j.cjtee.2020.04.003. ISSN 1008-1275. PMID 32417043.

- ↑ Hammer, Mark M.; Raptis, Demetrios A.; Mellnick, Vincent M.; Bhalla, Sanjeev; Raptis, Constantine A. (2017). "Traumatic injuries of the diaphragm: overview of imaging findings and diagnosis". Abdominal Radiology 42 (4): 1020–1027. doi:10.1007/s00261-016-0908-3. ISSN 2366-0058. PMID 27641159. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27641159/.

- ↑ Morgan, B. S.; Watcyn-Jones, T.; Garner, J. P. (2010). "Traumatic diaphragmatic injury". Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 156 (3): 139–144. doi:10.1136/jramc-156-03-02. ISSN 0035-8665. PMID 20919612. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20919612/.

- ↑ Pearson, A. S.; Wolford, R. W. (2000). "Management of skin trauma". Primary Care 27 (2): 475–492. doi:10.1016/s0095-4543(05)70208-6. ISSN 0095-4543. PMID 10815056. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10815056/.

- ↑ Ahmadi, Alireza; Bazargan-Hejazi, Shahrzad; Heidari Zadie, Zahra; Euasobhon, Pramote; Ketumarn, Penkae; Karbasfrushan, Ali; Amini-Saman, Javad; Mohammadi, Reza (2016). "Pain management in trauma: A review study". Journal of Injury & Violence Research 8 (2): 89–98. doi:10.5249/jivr.v8i2.707. ISSN 2008-4072. PMID 27414816.

- ↑ Peate, Ian; Evans, Suzanne; Clegg, Lisa (2022). "Chapter 8: Analgesics.". Fundamentals of pharmacology for paramedics. Chichester, West Sussex. ISBN 978-1-119-72428-5. OCLC 1284288277. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1284288277.

- ↑ Teixeira Lopes, Maria Carolina Barbosa; de Aguiar, Wagner; Yamaguchi Whitaker, Iveth (2019). "In-hospital Complications in Trauma Patients According to Injury Severity". Journal of Trauma Nursing 26 (1): 10–16. doi:10.1097/JTN.0000000000000411. ISSN 1078-7496. PMID 30624377. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30624377/.

- ↑ Bowler, Philip G. (2002). "Wound pathophysiology, infection and therapeutic options". Annals of Medicine 34 (6): 419–427. doi:10.1080/078538902321012360. ISSN 0785-3890. PMID 12523497. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12523497/.

- ↑ Graham, Patrick (2019). "Post-Traumatic Hematoma". Orthopedic Nursing 38 (3): 214–216. doi:10.1097/NOR.0000000000000559. ISSN 1542-538X. PMID 31124875. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31124875/.

- ↑ Kelley, Dorothy M. (2005). "Hypovolemic shock: an overview". Critical Care Nursing Quarterly 28 (1): 2–19; quiz 20–21. doi:10.1097/00002727-200501000-00002. ISSN 0887-9303. PMID 15732421. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15732421/.

- ↑ Agarwal, Tulika Mehta; Muneer, Mohammed; Asim, Mohammad; Awad, Malaz; Afzal, Yousra; Al-Thani, Hassan; Alhassan, Ahmed; Mollazehi, Monira et al. (2020). "Psychological trauma in different mechanisms of traumatic injury: A hospital-based cross-sectional study". PLOS ONE 15 (11): e0242849. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0242849. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 33253298. Bibcode: 2020PLoSO..1542849A.

- ↑ Craig, A. R.; Hancock, K; Chang, E (1994-01-01). "The influence of spinal cord injury on coping styles and self-perceptions two years after the injury". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 28 (2): 307–312. doi:10.1080/00048679409075644. ISSN 0004-8674. PMID 7993287. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00048679409075644.

- ↑ Tzonichaki, Loanna; Kleftaras, George (2002). "Paraplegia from Spinal Cord Injury: Self-Esteem, Loneliness, and Life Satisfaction" (in en). OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health 22 (3): 96–103. doi:10.1177/153944920202200302. ISSN 1539-4492. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/153944920202200302.

- ↑ Aacovou, I. (2005-06-30). "The Role of the Nurse in the Rehabilitation of Patients with Radical Changes in Body Image Due to Burn Injuries". Annals of Burns and Fire Disasters 18 (2): 89–94. ISSN 1592-9558. PMID 21990985.

- ↑ Fauerbach, James A.; Heinberg, Leslie J.; Lawrence, John W.; Munster, Andrew M.; Palombo, Debra A.; Richter, Daniel; Spence, Robert J.; Stevens, Sandra S. et al. (2000). "Effect of Early Body Image Dissatisfaction on Subsequent Psychological and Physical Adjustment After Disfiguring Injury" (in en-US). Psychosomatic Medicine 62 (4): 576–582. doi:10.1097/00006842-200007000-00017. ISSN 0033-3174. PMID 10949104. https://journals.lww.com/psychosomaticmedicine/Abstract/2000/07000/Effect_of_Early_Body_Image_Dissatisfaction_on.17.aspx.

- ↑ Orr, D. A.; Reznikoff, M.; Smith, G. M. (1989-09-01). "Body Image, Self-Esteem, and Depression in Burn-Injured Adolescents and Young Adults". The Journal of Burn Care & Rehabilitation 10 (5): 454–461. doi:10.1097/00004630-198909000-00016. ISSN 0273-8481. PMID 2793926. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004630-198909000-00016.

- ↑ Kaney, Sue (2005), "Burns and social stigma", Stigma and Social Exclusion in Healthcare: pp. 154–162, doi:10.4324/9780203995501-22, ISBN 9780203995501, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203995501-22/burns-social-stigma-sue-kaney

- ↑ Halioua, Rebecca L.; Williams, Richard S. T.; Murray, Nicholas P.; Skalko, Thomas K.; Vogelsong, Hans G. (2011). "Staring and Perceptions of People with Facial Disfigurement". Therapeutic Recreation Journal 45 (4): 341–356.

- ↑ van der Sluis, C. K.; Eisma, W. H.; Groothoff, J. W.; ten Duis, H. J. (1998). "Long-term physical, psychological and social consequences of severe injuries". Injury 29 (4): 281–285. doi:10.1016/s0020-1383(97)00199-x. ISSN 0020-1383. PMID 9743748. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9743748/.

- ↑ Hardy, Charles J.; Richman, Jack M.; Rosenfeld, Lawrence B. (1991). "The Role of Social Support in the Life Stress/Injury Relationship". The Sport Psychologist 5 (2): 128–139. doi:10.1123/tsp.5.2.128. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232561401.

- ↑ Ivarsson, Andreas; Johnson, Urban; Andersen, Mark B.; Tranaeus, Ulrika; Stenling, Andreas; Lindwall, Magnus (2017). "Psychosocial Factors and Sport Injuries: Meta-analyses for Prediction and Prevention". Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) 47 (2): 353–365. doi:10.1007/s40279-016-0578-x. ISSN 1179-2035. PMID 27406221. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27406221/.

- ↑ Yang, Jingzhen; Peek-Asa, Corinne; Lowe, John B.; Heiden, Erin; Foster, Danny T. (2010-07-01). "Social Support Patterns of Collegiate Athletes Before and After Injury". Journal of Athletic Training 45 (4): 372–379. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-45.4.372. ISSN 1062-6050. PMID 20617912. PMC 2902031. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-45.4.372.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wounds. |

- International Trauma Conferences (registered trauma charity providing trauma education for medical professionals worldwide)

- Trauma.org (trauma resources for medical professionals)

- Emergency Medicine Research and Perspectives (emergency medicine procedure videos)

- American Trauma Society

- Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine

|