Physics:Magnetic potential

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

The term magnetic potential can be used for either of two quantities in classical electromagnetism: the magnetic vector potential, or simply vector potential, A; and the magnetic scalar potential ψ. Both quantities can be used in certain circumstances to calculate the magnetic field B.

The more frequently used magnetic vector potential is defined so that its curl is equal to the magnetic field: [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla \times \mathbf{A}=\mathbf{B}\, }[/math]. Together with the electric potential φ, the magnetic vector potential can be used to specify the electric field E as well. Therefore, many equations of electromagnetism can be written either in terms of the fields E and B, or equivalently in terms of the potentials φ and A. In more advanced theories such as quantum mechanics, most equations use potentials rather than fields.

The magnetic scalar potential ψ is sometimes used to specify the magnetic H-field in cases when there are no free currents, in a manner analogous to using the electric potential to determine the electric field in electrostatics. One important use of ψ is to determine the magnetic field due to permanent magnets when their magnetization is known. With some care the scalar potential can be extended to include free currents as well.[citation needed]

Historically, Lord Kelvin first introduced vector potential in 1851, along with the formula relating it to the magnetic field.[1]

Magnetic vector potential

The magnetic vector potential A is a vector field, defined along with the electric potential ϕ (a scalar field) by the equations:[2]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{B} = \nabla \times \mathbf{A}\,,\quad \mathbf{E} = -\nabla\phi - \frac{ \partial \mathbf{A} }{ \partial t }\,, }[/math]

where B is the magnetic field and E is the electric field. In magnetostatics where there is no time-varying charge distribution, only the first equation is needed. (In the context of electrodynamics, the terms vector potential and scalar potential are used for magnetic vector potential and electric potential, respectively. In mathematics, vector potential and scalar potential can be generalized to higher dimensions.)

If electric and magnetic fields are defined as above from potentials, they automatically satisfy two of Maxwell's equations: Gauss's law for magnetism and Faraday's Law. For example, if A is continuous and well-defined everywhere, then it is guaranteed not to result in magnetic monopoles. (In the mathematical theory of magnetic monopoles, A is allowed to be either undefined or multiple-valued in some places; see magnetic monopole for details).

Starting with the above definitions:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \nabla \cdot \mathbf{B} &= \nabla \cdot \left(\nabla \times \mathbf{A}\right) = 0 \\ \nabla \times \mathbf{E} &= \nabla \times \left( -\nabla\phi - \frac{ \partial\mathbf{A} }{ \partial t } \right) = -\frac{ \partial }{ \partial t } \left(\nabla \times \mathbf{A}\right) = -\frac{ \partial \mathbf{B} }{ \partial t }. \end{align} }[/math]

Alternatively, the existence of A and ϕ is guaranteed from these two laws using Helmholtz's theorem. For example, since the magnetic field is divergence-free (Gauss's law for magnetism; i.e., ∇ ⋅ B = 0), A always exists that satisfies the above definition.

The vector potential A is used when studying the Lagrangian in classical mechanics and in quantum mechanics (see Schrödinger equation for charged particles, Dirac equation, Aharonov–Bohm effect).

In the SI system, the units of A are V·s·m−1 and are the same as that of momentum per unit charge, or force per unit current.

The line integral of A over a close loop is equal to the magnetic flux through the enclosed surface:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \oint_\Gamma \mathbf{A}\, \cdot\, d{\mathbf{\Gamma}} = \iint_S \nabla\times\mathbf{A}\, \cdot\, d\mathbf{S}=\Phi_B. }[/math]

Therefore, the units of A are also equivalent to Weber per metre. The above equation is useful in the flux quantization of superconducting loops.

Although the magnetic field B is a pseudovector (also called axial vector), the vector potential A is a polar vector.[3] This means that if the right-hand rule for cross products were replaced with a left-hand rule, but without changing any other equations or definitions, then B would switch signs, but A would not change. This is an example of a general theorem: The curl of a polar vector is a pseudovector, and vice versa.[3]

Gauge choices

The above definition does not define the magnetic vector potential uniquely because, by definition, we can arbitrarily add curl-free components to the magnetic potential without changing the observed magnetic field. Thus, there is a degree of freedom available when choosing A. This condition is known as gauge invariance.

Maxwell's equations in terms of vector potential

Using the above definition of the potentials and applying it to the other two Maxwell's equations (the ones that are not automatically satisfied) results in a complicated differential equation that can be simplified using the Lorenz gauge where A is chosen to satisfy:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla\cdot\mathbf{A} + \frac{1}{c^2} \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial t} = 0. }[/math][2]

Using the Lorenz gauge, Maxwell's equations can be written compactly in terms of the magnetic vector potential A and the electric scalar potential ϕ:[2]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \nabla^2\phi - \frac{1}{c^2}\frac{\partial^2 \phi}{\partial t^2} &= -\frac{\rho}{\epsilon_0} \\ \nabla^2\mathbf{A} - \frac{1}{c^2}\frac{\partial^2 \mathbf{A}}{\partial t^2} &= -\mu_0 \mathbf{J} \end{align} }[/math]

In other gauges, the equations are different. A different notation to write these same equations (using four-vectors) is shown below.

Calculation of potentials from source distributions

The solutions of Maxwell's equations in the Lorenz gauge (see Feynman[2] and Jackson[4]) with the boundary condition that both potentials go to zero sufficiently fast as they approach infinity are called the retarded potentials, which are the magnetic vector potential A(r, t) and the electric scalar potential ϕ(r, t) due to a current distribution of current density J(r′, t′), charge density ρ(r′, t′), and volume Ω, within which ρ and J are non-zero at least sometimes and some places):

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \mathbf{A} \left(\mathbf{r}, t\right) &= \frac{\mu_0}{4\pi} \int_\Omega \frac{\mathbf{J}\left(\mathbf{r}' , t'\right)}{\left|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}'\right|}\, \mathrm{d}^3\mathbf{r}' \\ \phi \left(\mathbf{r}, t\right) &= \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \int_\Omega \frac{\rho \left(\mathbf{r}', t'\right)}{\left|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}'\right|}\, \mathrm{d}^3\mathbf{r}' \end{align} }[/math]

where the fields at position vector r and time t are calculated from sources at distant position r′ at an earlier time t′. The location r′ is a source point in the charge or current distribution (also the integration variable, within volume Ω). The earlier time t′ is called the retarded time, and calculated as

- [math]\displaystyle{ t' = t - \frac{\left|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}'\right|}{c} }[/math].

There are a few notable things about A and ϕ calculated in this way:

- (The Lorenz gauge condition): [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla\cdot\mathbf{A} + \frac{1}{c^2}\frac{\partial\phi}{\partial t} = 0 }[/math] is satisfied.

- The position of r, the point at which values for ϕ and A are found, only enters the equation as part of the scalar distance from r′ to r. The direction from r′ to r does not enter into the equation. The only thing that matters about a source point is how far away it is.

- The integrand uses retarded time, t′. This simply reflects the fact that changes in the sources propagate at the speed of light. Hence the charge and current densities affecting the electric and magnetic potential at r and t, from remote location r′ must also be at some prior time t′.

- The equation for A is a vector equation. In Cartesian coordinates, the equation separates into three scalar equations:[5]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} A_x\left(\mathbf{r}, t\right) &= \frac{\mu_0}{4\pi} \int_\Omega\frac{J_x\left(\mathbf{r}', t'\right)}{\left|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}'\right|}\,\mathrm{d}^3\mathbf{r}' \\ A_y\left(\mathbf{r}, t\right) &= \frac{\mu_0}{4\pi} \int_\Omega\frac{J_y\left(\mathbf{r}', t'\right)}{\left|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}'\right|}\,\mathrm{d}^3\mathbf{r}' \\ A_z\left(\mathbf{r}, t\right) &= \frac{\mu_0}{4\pi} \int_\Omega\frac{J_z\left(\mathbf{r}', t'\right)}{\left|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}'\right|}\,\mathrm{d}^3\mathbf{r}' \end{align} }[/math]

- In this form it is easy to see that the component of A in a given direction depends only on the components of J that are in the same direction. If the current is carried in a long straight wire, the A points in the same direction as the wire.

In other gauges, the formula for A and ϕ is different; for example, see Coulomb gauge for another possibility.

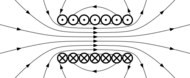

Depiction of the A-field

See Feynman[6] for the depiction of the A field around a long thin solenoid.

Since

- [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla \times \mathbf{B} = \mu_0\mathbf{J} }[/math]

assuming quasi-static conditions, i.e.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial E}{\partial t}\rightarrow 0\,\quad \nabla \times \mathbf{A} = \mathbf{B} \,, }[/math]

the lines and contours of A relate to B like the lines and contours of B relate to j. Thus, a depiction of the A field around a loop of B flux (as would be produced in a toroidal inductor) is qualitatively the same as the B field around a loop of current.

The figure to the right is an artist's depiction of the A field. The thicker lines indicate paths of higher average intensity (shorter paths have higher intensity so that the path integral is the same). The lines are drawn to (aesthetically) impart the general look of the A-field.

The drawing tacitly assumes ∇ ⋅ A = 0, true under one of the following assumptions:

- the Coulomb gauge is assumed

- the Lorenz gauge is assumed and there is no distribution of charge, ρ = 0,

- the Lorenz gauge is assumed and zero frequency is assumed

- the Lorenz gauge is assumed and a non-zero frequency that is low enough to neglect [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{c}\frac{\partial\phi}{\partial t} }[/math] is assumed

Electromagnetic four-potential

In the context of special relativity, it is natural to join the magnetic vector potential together with the (scalar) electric potential into the electromagnetic potential, also called four-potential.

One motivation for doing so is that the four-potential is a mathematical four-vector. Thus, using standard four-vector transformation rules, if the electric and magnetic potentials are known in one inertial reference frame, they can be simply calculated in any other inertial reference frame.

Another, related motivation is that the content of classical electromagnetism can be written in a concise and convenient form using the electromagnetic four potential, especially when the Lorenz gauge is used. In particular, in abstract index notation, the set of Maxwell's equations (in the Lorenz gauge) may be written (in Gaussian units) as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \partial^\mu A_\mu &= 0 \\ \Box A_\mu &= \frac{4\pi}{c} J_\mu \end{align} }[/math]

where □ is the d'Alembertian and J is the four-current. The first equation is the Lorenz gauge condition while the second contains Maxwell's equations. The four-potential also plays a very important role in quantum electrodynamics.

Magnetic scalar potential

The scalar potential is another useful quantity in describing the magnetic field, especially for permanent magnets.

In a simply connected domain where there is no free current,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla\times\mathbf{H} = 0, }[/math]

hence we can define a magnetic scalar potential, ψ, as[7]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{H} = -\nabla\psi. }[/math]

Using the definition of H:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla\cdot\mathbf{B} = \mu_{0}\nabla\cdot\left(\mathbf{H} + \mathbf{M}\right) = 0, }[/math]

it follows that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla^2 \psi = -\nabla\cdot\mathbf{H} = \nabla\cdot\mathbf{M}. }[/math]

Here, ∇ ⋅ M acts as the source for magnetic field, much like ∇ ⋅ P acts as the source for electric field. So analogously to bound electric charge, the quantity

- [math]\displaystyle{ \rho_m = -\nabla\cdot\mathbf{M} }[/math]

is called the bound magnetic charge.

If there is free current, one may subtract the contribution of free current per Biot–Savart law from total magnetic field and solve the remainder with the scalar potential method. To date there has not been any reproducible evidence for the existence of magnetic monopoles.[8]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Yang, ChenNing (2014). "The conceptual origins of Maxwell’s equations and gauge theory". Physics Today 67 (11): 45–51. doi:10.1063/PT.3.2585. Bibcode: 2014PhT....67k..45Y.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 (Feynman 1964)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Tensors and pseudo-tensors, lecture notes by Richard Fitzpatrick

- ↑ (Jackson 1999)

- ↑ (Kraus 1984)

- ↑ (Feynman 1964)

- ↑ (Vanderlinde 2005)

- ↑ Griffiths, David (2013). Introduction to Electrodynamics. Pearson. pp. 241–242. ISBN 9780321856562.

References

- Duffin, W.J. (1990). Electricity and Magnetism, Fourth Edition. McGraw-Hill.

- Feynman, Richard P; Leighton, Robert B; Sands, Matthew (1964). The Feynman Lectures on Physics Volume 2. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-02117-X.

- Jackson, John David (1999), Classical Electrodynamics (3rd ed.), John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-30932-X

- Kraus, John D. (1984), Electromagnetics (3rd ed.), McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-035423-5, https://archive.org/details/electromagnetics00krau

- Ulaby, Fawwaz (2007). Fundamentals of Applied Electromagnetics, Fifth Edition. Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 226–228. ISBN 0-13-241326-4.

- Vanderlinde, Jack (2005). Classical Electromagnetic Theory. ISBN 1-4020-2699-4. http://www.springerlink.com/index/10.1007/1-4020-2700-1.