Medicine:Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

| Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | alveolar proteinosis |

| |

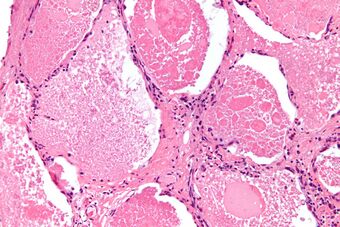

| Micrograph of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, showing the characteristic airspace filling with focally dense globs referred to as chatter or dense bodies. H&E stain. | |

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) is a rare lung disorder characterized by an abnormal accumulation of surfactant-derived lipoprotein compounds within the alveoli of the lung. The accumulated substances interfere with the normal gas exchange and expansion of the lungs, ultimately leading to difficulty breathing and a predisposition to developing lung infections. The causes of PAP may be grouped into primary (autoimmune PAP, hereditary PAP), secondary (multiple diseases), and congenital (multiple diseases, usually genetic) causes, although the most common cause is a primary autoimmune condition in an individual.

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of PAP include shortness of breath,[1] cough, low grade fever, and weight loss. Additionally, the clinical course of PAP is unpredictable. Spontaneous remission is recognized, and some patients have stable symptoms. Death may occur due to the progression of PAP or of any underlying associated disease. Individuals with PAP are more vulnerable to lung infections such as nocardiosis, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection, or fungal infections.[1]

Causes

The abnormal accumulation of lipoproteinaceous compounds in PAP is due to impaired surfactant regulation and clearance. This is usually related to impaired alveolar macrophage function.[2] In adults, the most common cause of PAP is an autoimmunity to granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), a critical factor in development of alveolar macrophages. Decreased bioavailability of GM-CSF results in poor alveolar macrophages development and function, which results in accumulation of surfactant and related products.[2]

Secondary causes of PAP are those in which the accumulation of lipoproteinaceous compounds is secondary to another disease process. This has been recognized in the settings of certain cancers (such as myeloid leukemia), lung infections, or environmental exposure to dusts or chemicals, such as nickel.[3]

Although the cause of PAP was not originally understood, a major breakthrough in the understanding of the cause of the disease came by the chance observation that mice bred for experimental study to lack a hematologic growth factor known as granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) developed a pulmonary syndrome of abnormal surfactant accumulation resembling human PAP.[4]

The implications of this finding are still being explored, but significant progress was reported in February 2007. Researchers in that report discussed the presence of anti-GM-CSF autoantibodies in patients with PAP, and duplicated that syndrome with the infusion of these autoantibodies into mice.[5]

Familial or sporadic inactivating mutations in one of the two parental GATA2 genes produces an autosomal dominant disorder termed GATA2 deficiency. The GATA2 gene produces the GATA2 transcription factor which is critical for the embryonic development, maintenance, and functionality of blood-forming, lympathic-forming, and other tissue-forming cells. Individuals with a single GATA2 inactivating mutation present with a wide range of disorders including pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. GATA2 mutation-based pulmonary alveolar proteinosis is associated with normal levels of GM-CSF and commonly improves or is avoided in afflicted individuals who successfully receive a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.[6][7]

Genetics

Hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis is a recessive genetic condition in which individuals are born with genetic mutations that deteriorate the function of the CSF2 receptor alpha on alveolar macrophages. Consequently, a messenger molecule known as granulocyte/macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is unable to stimulate alveolar macrophages to clear surfactant, leading to difficulty with breathing. The gene for the CSF2 receptor alpha is located in the 5q31 region of chromosome 5, and the gene product can also be referred to as granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor.[8][9]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PAP is made using a combination of a person's symptoms, chest imaging, and microscopic evaluation of lung washing/tissue. Additional testing for serum anti-GM-CSF antibodies are helpful for confirmation.[10]

Although both the symptoms and imaging findings are stereotypical and well-described, they are non-specific and indistinguishable from many other conditions. For example, chest x-ray may show alveolar opacities, and a CT may show a crazy paving lung pattern, both of which are seen more commonly in numerous other conditions.[11] Thus, the diagnosis primarily depends on the pathology findings.[citation needed]

Lung washings or tissue for histopathologic analysis are most commonly obtained using bronchoalveolar lavage and/or lung biopsy.[12] Characteristic biopsy findings show filling of the alveoli (and sometimes terminal bronchioles) with an amorphous eosinophilic material, which stains strongly positive on PAS stain and the PAS diastase stain. The surrounding alveoli and pulmonary interstitium remain relatively normal.[13] Electron microscopy of the sample, although not typically performed due to impracticality, shows lamellated bodies representing surfactant.[14] An alternative diagnosis with similar histomorphologic findings is Pneumocystis jirovicii pneumonia.[14]

Lung washings characteristically yield a fluid which is "milky"composition. Under the microscope, samples show 20-50 micrometer PAS-positive globules on a background of finely granular or amorphous PAS-positive material. There is typically a low numbers of macrophages and inflammatory cells (although this is variable).[13][14]

Treatment

The standard treatment for PAP is whole-lung lavage[15][16][17] and supportive care.[18][19][20] Whole lung lavage is a procedure performed under general anesthesia, in which one lung is pumped with oxygen (ventilated lung), and the other lung (non-ventilated lung) is filled with a warm saline solution (up to 20 L) and drained, removing any proteinaceous effluent along with it.[21] This is generally effective at improving PAP symptoms, often for a prolonged period of time. Other treatments still being studied include subcutaneous and inhaled GM-CSF, and rituximab, an intravenous infusion that works to stop the production of the autoantibodies responsible for autoimmune PAP.[18][19][20][22] Lung transplantation has been performed in individuals with the various forms of PAP; however, this is often only used when all other treatment options have failed and significant lung damage has developed due to the risks, complications, or recurrence of PAP following transplantation.[20][22][23] As of 2022, methionine oral supplementation has been tested on patients with methionine tRNA synthetase-related PAP and has strong evidence of its efficacy on these patients. [24]

Epidemiology

The disease is more common in males and in tobacco smokers.[citation needed]

In a recent epidemiologic study from Japan,[25] Autoimmune PAP has an incidence and prevalence higher than previously reported and is not strongly linked to smoking, occupational exposure, or other illnesses. Endogenous lipoid pneumonia and non-specific interstitial pneumonitis has been seen prior to the development of PAP in a child.[26]

History

PAP was first described in 1958[27] by the physicians Samuel Rosen, Benjamin Castleman, and Averill Liebow.[28] In their case series published in the New England Journal of Medicine on June 7 of that year, they described 27 patients with pathologic evidence of periodic acid Schiff positive material filling the alveoli. This lipid rich material was subsequently recognized to be surfactant.[citation needed]

The reported treatment of PAP using therapeutic bronchoalveolar lavage was in 1960 by Dr. Jose Ramirez-Rivera at the Veterans' Administration Hospital in Baltimore,[29] who described repeated "segmental flooding" as a means of physically removing the accumulated alveolar material.[30]

Research

PAP is one of the rare lung diseases currently being studied by the Rare Lung Diseases Consortium. The consortium is part of the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network, an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research, of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and dedicated to developing new diagnostics and therapeutics for patients with rare lung diseases, through collaboration between the National Institutes of Health, patient organizations and clinical investigators.[citation needed]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: clinical aspects and current concepts on pathogenesis". Thorax 55 (1): 67–77. January 2000. doi:10.1136/thorax.55.1.67. PMID 10607805.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in adults: pathophysiology and clinical approach". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine 6 (7): 554–565. July 2018. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(18)30043-2. PMID 29397349.

- ↑ "Inhalation carcinogenicity study with nickel metal powder in Wistar rats". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 233 (2): 262–75. December 2008. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2008.08.017. PMID 18822311.

- ↑ "Granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor-deficient mice show no major perturbation of hematopoiesis but develop a characteristic pulmonary pathology". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91 (12): 5592–6. June 1994. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.12.5592. PMID 8202532. Bibcode: 1994PNAS...91.5592S.

- ↑ "GM-CSF autoantibodies and neutrophil dysfunction in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis". The New England Journal of Medicine 356 (6): 567–79. February 2007. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa062505. PMID 17287477.

- ↑ "GATA factor mutations in hematologic disease". Blood 129 (15): 2103–2110. April 2017. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-09-687889. PMID 28179280.

- ↑ "Heterogeneity of GATA2-related myeloid neoplasms". International Journal of Hematology 106 (2): 175–182. August 2017. doi:10.1007/s12185-017-2285-2. PMID 28643018.

- ↑ “Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis.” NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders), 16 Jan. 2020, rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/pulmonary-alveolar-proteinosis/.

- ↑ "Diseases of pulmonary surfactant homeostasis". Annual Review of Pathology 10: 371–93. 2015. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104644. PMID 25621661.

- ↑ "Standardized serum GM-CSF autoantibody testing for the routine clinical diagnosis of autoimmune pulmonary alveolar proteinosis". Journal of Immunological Methods 402 (1–2): 57–70. January 2014. doi:10.1016/j.jim.2013.11.011. PMID 24275678.

- ↑ "CT features of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology 176 (5): 1287–94. May 2001. doi:10.2214/ajr.176.5.1761287. PMID 11312196.

- ↑ "Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: an overview for internists and hospital physicians". Hospital Practice 38 (1): 43–9. February 2010. doi:10.3810/hp.2010.02.277. PMID 20469623.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: diagnosis using routinely processed smears of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid". Journal of Clinical Pathology 50 (12): 981–4. December 1997. doi:10.1136/jcp.50.12.981. PMID 9516877.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: a spectrum of cytologic, histochemical, and ultrastructural findings in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid". Diagnostic Cytopathology 24 (6): 389–95. June 2001. doi:10.1002/dc.1086. PMID 11391819.

- ↑ "Successful whole lung lavage in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis secondary to lysinuric protein intolerance: a case report". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2: 14. March 2007. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-14. PMID 17386098.

- ↑ "Whole lung lavage in the treatment of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis". Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing 20 (2): 114–26. April 2005. doi:10.1016/j.jopan.2005.01.005. PMID 15806528.

- ↑ "Long-term follow-up and treatment of congenital alveolar proteinosis". BMC Pediatrics 11 (1): 72. August 2011. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-11-72. PMID 21849033.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis (PAP) Management and Treatment". https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17398-pulmonary-alveolar-proteinosis-pap/management-and-treatment.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "UpToDate". https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-and-prognosis-of-pulmonary-alveolar-proteinosis-in-adults#H8.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 "Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis" (in en-US). https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/pulmonary-alveolar-proteinosis/.

- ↑ "Whole-lung lavage for pulmonary alveolar proteinosis" (in English). Chest 136 (6): 1678–1681. December 2009. doi:10.1378/chest.09-2295. PMID 19995769.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis: A Comprehensive Clinical Perspective". Pediatrics 140 (2): e20170610. August 2017. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-0610. PMID 28771412.

- ↑ "Lung transplantation in children". Annals of Surgery 236 (3): 270–6. September 2002. doi:10.1097/00000658-200209000-00003. PMID 12192313.

- ↑ Bonella, Francesco; Borie, Raphael (1 April 2022). "Targeted therapy for pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: the time is now" (in en). European Respiratory Journal 59 (4). doi:10.1183/13993003.02971-2021. PMID 35450922. https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/59/4/2102971. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ↑ "Characteristics of a large cohort of patients with autoimmune pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in Japan". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 177 (7): 752–62. April 2008. doi:10.1164/rccm.200708-1271OC. PMID 18202348.

- ↑ "Endogenous lipoid pneumonia preceding diagnosis of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis". The Clinical Respiratory Journal 10 (2): 246–9. March 2016. doi:10.1111/crj.12197. PMID 25103284.

- ↑ "Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: progress in the first 44 years". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 166 (2): 215–35. July 2002. doi:10.1164/rccm.2109105. PMID 12119235.

- ↑ "Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis". The New England Journal of Medicine 258 (23): 1123–42. June 1958. doi:10.1056/NEJM195806052582301. PMID 13552931.

- ↑ "Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Diagnostic technics and observations". The New England Journal of Medicine 268 (4): 165–71. January 1963. doi:10.1056/NEJM196301242680401. PMID 13990655.

- ↑ "Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis: A New Technique and Rational for Treatment". Archives of Internal Medicine 112 (3): 419–31. September 1963. doi:10.1001/archinte.1963.03860030173021. PMID 14045290.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|