Medicine:Epidemiology of suicide

There are more than 700,000 estimated suicide deaths every year.[1] Suicide affects every demographic, yet there are some populations that are more impacted than others. For example, among 15–29 year olds, suicide is much more prominent; this being the fourth leading cause[1] of death within this age group.

Suicide is a worldwide issue which is disproportionally affecting low-income countries, with 77%[1] of the total death rate from these areas.

There are many competing factors that come into play when determining the epidemiology of suicide such as biological sex, race and sexual orientation, religion, social determinants of health, and seasonal trends.

Overview

Suicide rates are actively increasing around the globe. It is an increasingly common idealization, with someone considering taking their own life every 40 seconds.[2] From the years 2000-2021 suicide rates have gone up approximately 36%.[3]

The cause of this increased risk of suicide can be attributed multiple factors. While there is no single defined cause of suicide, there are three overarching themes when it comes to causation: health, environmental and historical factors.[4]

Health causes could be related to mental health diagnosis such as depression, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders or traumatic brain injuries.[4] Around 46% of suicide cases had previously been diagnosed with a mental health disorder. This is a fluctuating estimate due to the fact that mental health is often overlooked and under reported.

Environmental causes could be access to weapons or drugs, childhood stress or exposures to other abuses.[4] Bullying is a common catalyst as it increases social isolation and self deprivation in the same prolonged instances. "According to studies by Yale University, victims of bullying are between 2 to 9 times more likely to consider suicide than non-victims."[5]

Historical factors also play a role. Exposure to suicide in the developmental years can put an individual at increased risk of their own death.[4] Many studies[6] have been conducted to conclude that suicide contagion is a serious problem, especially for young people. Suicide can be facilitated in vulnerable teens by exposure to real or fictional accounts of suicide, including media coverage of suicide, such as intensive reporting of the suicide of a celebrity or idol.[7]

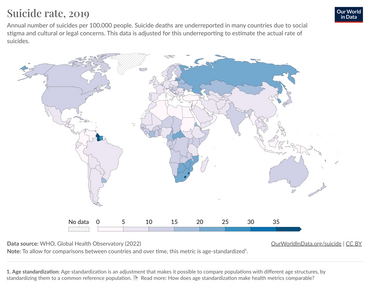

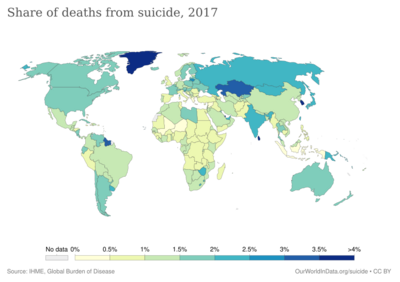

Geography- Country

As of 2019, the highest annual number of suicides per 100,000 people was in Lesotho, with a rate of 87.5 deaths per 100,000 people. The second country being Guyana with 40.9 deaths per 100,000 people and third Eswatini, with 40.5 deaths per 100,000 people.[9]

Low-income countries share the burden of suicidal persons due to their impoverished state[10] which explains the top three countries on the suicide rate list.

In other parts of the world, suicide rates are not as extreme, but the issue of suicide is still extremely apparent.

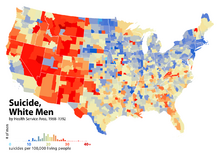

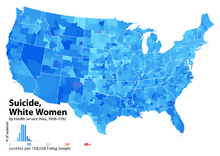

About 21.6 suicide deaths per 100,000 people occur in Russia every year;[9] in southern Africa, the average is about 21 deaths per 100,000 people.[9] The United States reports about 14.5 deaths annually per 100,000 people, however, this rate is steadily increasing. In the 2000s, that rate was 10 people per year.[9] Within countries there is variety as well. As of 2021, Wyoming is the leading state in annual suicide with 32.3 deaths per 100,000 people. On the other hand, New Jersey, has the lowest suicide rate with 7.1 deaths per 100,000 people.[11]

Rural and urban areas show differences as well. "The suicide rate is nearly twice as great in the most rural areas of the U.S. compared to the most urban areas (18.9 per 100,000 people in rural areas vs. 13.2 per 100,000 people in urban areas)."[12] This could be due to a number of factors such as physical isolation,[13] limited access to mental health services,[14] increased access to lethal means[15] or stigma regarding mental health.[16]

Sex

In the United States , males are four times more likely to die by suicide than females, although more women than men report suicide attempts and self-harm with suicidal intentions. Male suicide rates are far higher than females in all age groups (the ratio varies from 3:1 to 10:1). In other western countries, males are also much more likely to die by suicide than females (usually by a factor of 3–4:1). It was the 8th leading cause of death for males, and 19th leading cause of death for females.[17]

Excess male mortality from suicide is generally lower in non-Western nations. In eight countries, including China with about one-fifth of the world population, the rate of male mortality from suicide is lower than that for females, with females more likely to die by suicide by a factor of 1.3–1.6[19][20]

Age

Nearly half of all Suicides in the United States are accounted for in the age range of 35–64 years. Adults aged 75 and older are at increased risk of suicide rates (20.3 per 100,000).[21] However suicide may be a lower percentage accounting for all suicides across the United States, in a subgroup of ages 10–24 it is the second leading cause of death.

Race and sexual orientation

Race

Research across the United States shows that across all age groups, Non-Hispanic Alaskan Natives and American Indians are at the highest risk of suicide. In years 2018–2021, suicide rates significantly increased within these populations.[21]

In 2003 in the United States, Whites and Asians were nearly 2.5 times more likely to kill themselves than Blacks or Mexicans.[22] In the eastern portion of the world (primarily in Asian and Pacific-Island countries), the numbers of reported suicides are growing every year.[23]

Sexual Orientation

The likelihood of suicide attempts are increased in both gay males and lesbians, as well as bisexuals of both sexes when compared to their heterosexual counterparts.[24][25][26] The trend of having a higher incident rate among females is no exception with lesbians or bisexual females, and when compared with homosexual males, lesbians are more likely to attempt suicide than gay or bisexual males.[27]

Evidence varies between studies with how increased the risk of suicide in the queer community in comparison to heterosexuals. The lowest reported increases stated suicide is 0.8–1.1 times more likely for queer females[28] and 1.5–2.5 times more likely for queer males.[29][30] The highest increases reach 4.6 more likely in females[31] and 14.6 more likely in males who do not identify as heterosexual.[32]

Race and age also play a factor in the increased risk. The highest ratios for males are for Caucasians in their youth. By the age of 25, their risk is down to less than half of what it was However gay Black males' risk steadily increases to 8.6 times more likely in this same age group. Lifetime risks are 5.7 times more for White and 12.8 times more for Black gay and bisexual males.[32]

In lesbian and bisexual females, age has opposite effect with fewer attempts in youth when compared to heterosexual females. Throughout their lifetime, the likelihood of LGBTQ+ females to attempt suicide nearly triples the youth ratio for Caucasian females, however for Black females, the rate is less significant (less than 0.1 to 0.3 difference) with heterosexual Black females having a slightly higher risk throughout most of the age-based study.[32]

Gay and lesbian youth who attempt suicide are disproportionately subject to anti-gay attitudes, and have weaker skills for coping with discrimination, isolation, and loneliness.[32][33] They were also more likely to experience family rejection than those who do not attempt suicide.[34] Another study found that gay and bisexual youth who attempted suicide had a more feminine gender presentation,[35] adopted an LGBTQ+ identity at a young age, and were more likely than their peers to report sexual abuse, drug abuse, and arrests for misconduct.[35]

There is evidence that same-sex sexual behavior, but not homosexual attraction or homosexual identity, was significantly predictive of suicide among Norwegian adolescents.[36] In Denmark, the age-adjusted suicide mortality risk for men in registered domestic partnerships was nearly eight times greater than for men with positive histories of heterosexual marriage, and nearly twice as high for men who had never married.[37]

A large study of suicide in Sweden involved the analysis of data records for 6,456 same-sex married couples and 1,181,723 man-women marriages. The study showed that even with Sweden's tolerant attitude regarding homosexuality, it was determined that for same-sex married men, the suicide risk was nearly three times higher than for different-sex married men, even after an adjustment for HIV status. For women, it was shown that there was a tentatively elevated suicide risk for same-sex married women over that of different-sex married women.[38]

Religion

- Every major religion in the world is opposed to suicide. However, the stringency of this belief depends on the individual. Teachings within religions may vary and different individuals may interpret these teachings differently.[39]

Suicide rates between different religions vary. Among the major religions in the US, Protestants have the highest rate of suicide. Roman Catholics had the next highest rate, followed by Jews and Muslims.[40]

In most cases, religiosity has been associated with reduced risk of suicide.[40] Collectively, individuals who reside in religious countries and are integrated into their religious community are less accepting of suicide[39][40] Compared to secular countries, suicide rates are lower in countries with a state religion.[39][40] A global study on atheism noted countries with higher levels of atheism had the highest suicide rates compared to countries with "statistically insignificant levels of organic atheism."[41] The People's Republic of China, which is an atheist state, had the highest suicide rate (25.6 per 100,000 persons).[42]

However, studies have been criticized for oversimplifying the relationship between religion and the risk of suicide, as this association can vary depending on culture. Religion may adversely affect mental health if there is discord between an individuals beliefs and their faith.[39] In some cases, religion may be related to a higher risk of suicide if it leads a person to feel guilty, isolated, or abandoned by the community.[43] Additionally, there is evidence to suggest that while religious affiliation protects against suicide attempts, it does not stop suicidal ideation.[40]

Social, Political and Economic Factors

Higher levels of social and national cohesion reduce suicide rates. Suicide levels are highest among the retired, unemployed, impoverished, divorced, the childless, empty nesters, and other people who live alone. Suicide rates also rise during times of economic uncertainty. (Although poverty is not a direct cause, it can contribute to the risk of suicide).[45][7]

Epidemiological studies generally show a relationship between suicide or suicidal behaviors and socio-economic disadvantage. Disadvantages include limited educational achievement, homelessness, unemployment, economic dependence, and contact with the police or justice system.[45] It has been shown for individuals who suffer from unemployment, the longer they are unemployed, the greater the risk of suicide.[7][46] Additionally, the lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation in the homeless community was 41.60% while the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempt was 28.88%.[47]

A 2015 UK study by the Office for National Statistics, commissioned by Public Health England, which considered 18,998 deaths of people aged between 20 and 64, found that the employment sectors with the highest incidence of suicide for men was construction, and for women culture, media and sport, healthcare, and primary school teaching.[48]

Men working in the construction industry and women employed in culture, media and sport, healthcare and primary school teaching are at the highest risk of suicide, official figures for England suggest.

Certain political constructs can act as protective factors against suicide. The most apparent factor is an increase in minimum wage which precedes inflation. Other factors include social welfare expenditures, and laws which restrict access to firearms and alcohol.[7]

Health

Mental Illness

Societally, mental disorders are highly associated with suicide risk and deaths. Statistically, there is data to support this. In high income countries, mental or substance abuse disorders can be attributed to 80% of suicide deaths. In low income countries, the percentage is slightly lower at 70%. Mental illnesses that have been associated with suicide risk include Major depressive disorder (MDD), anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, dysthymia, and schizophrenia.[50]

Physical Health Conditions

In addition to mental disorders, physical health issues have an impact on suicide risk. After adjusting for age, sex, mental health, and substance use diagnoses, nine conditions have been positively associated with suicide risk. The study claimed this association with the following conditions: back pain, brain injury, cancer, congestive heart failure, COPD, epilepsy, HIV/AIDS, migraine, and sleep disorders. The risk of suicide in people with traumatic brain injuries is almost nine times higher than normal which makes it the highest risk condition. Comorbidity of conditions was also shown to significantly increase the risk of suicide.[51]

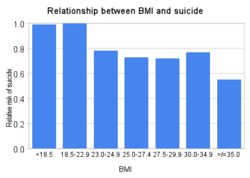

Body Mass Index

Risk of suicide may decrease with increased weight and is low in obese persons.[52] The connection is not well understood, but it is hypothesized that elevated body weight results in higher circulating levels of tryptophan, serotonin, and leptin, which in turn reduces impulsivity.[53]

However, other studies indicate that suicide rates increase with extreme obesity, and it is difficult to control for conflating factors such as BMI-related differences in longevity, which have a significant bearing on suicide rates.[54]

Physical Illness and Functional Disability in Older Adults

In adults aged 65 and older, suicidal behavior has been associated with certain functional disabilities and specific conditions. These positively associated conditions and disabilities are the following: malignant diseases, neurological disorders, pain, COPD, liver disease, male genital disorders, and arthritis. Generally speaking, illnesses that threaten the independence of a person, make them doubt their usefulness, value or dignity, or minimize their pleasure with life are more likely to be suicidogenic.[55]

Season

The idea that suicide is more common during the winter holidays (including Christmas in the northern hemisphere) is a myth, generally reinforced by media coverage associating suicide with the holiday season. The National Center for Health Statistics found that suicides drop during the winter months, and peak during spring and early summer.[56][57] Considering that there is a correlation between the winter season and rates of depression,[58] there are theories that this might be accounted for by capability to die by suicide and relative cheerfulness.[59]

Suicide has also been linked to other seasonal factors.[60]

Seasonal allergies have shown potential impacts on rates of suicide. Based on the reaction that allergens cause, animal models have shown an increase in anxiety-like behavior, reduced social interaction, and aggressive behavior which can be considered endophenotypes for suicidal behavior.[61]

There is significant variation in suicide risk by day of the week, which is greater than any seasonal variation.[62]

Trends

Certain time trends can be related to the type of death. In the United Kingdom for example, the steady rise in suicides from 1945 to 1963 may be due the removal of carbon monoxide from domestic gas supplies, which occurred with the change from coal gas to natural gas during the 1960s.[63]

Methods vary across cultures, and the easy availability of lethal agents and materials plays a role.[64]

Due to social stigma and misclassified cause of death, reported suicide rated are never exact. It is estimated that in the year 2000, global number of suicides were 791,855. As of 2019, there were 703,220 reported instances of suicide. This is a relative difference of 11%.[9] This trend shows a decrease in suicide deaths, however, there is contradicting evidence which shows an overall increase in suicide.[2] This discrepancy requires further research and comparison.

There is the possibility that one individual may have multiple suicide attempts, however, they can only have one completed suicide. Suicide attempts are up to 20 times more frequent than completed suicides.[65]

An increase in U.S. baseline temperature due to global warming projects an increase in suicide. With an increase between 1–6 degrees Celsius above the baseline, climate change‐attributable suicide in the United States is expected to increase from 283 to 1,660 cases.[66]

Historical data show lower suicide rates during periods of war.[67][68][69][70] However, this has been questioned in more recent studies, which showed a more complex picture than was previously conceived.[71][72] More research is required to fully understand this complicated relationship.

See also

- Copycat suicide

- Suicide epidemic

- Suicide in the military

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Suicide" (in en). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Bachmann, Silke (2018-07-06). "Epidemiology of Suicide and the Psychiatric Perspective" (in en). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (7): 1425. doi:10.3390/ijerph15071425. ISSN 1660-4601. PMID 29986446.

- ↑ "Facts About Suicide | Suicide | CDC" (in en-us). 2023-07-06. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/index.html.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Risk factors, protective factors, and warning signs" (in en). https://afsp.org/risk-factors-protective-factors-and-warning-signs/#risk-factors.

- ↑ Shireen, Farhat (1969-12-31). "Trauma experience of youngsters and Teens: A key issue in suicidal behavior among victims of bullying?". Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences 30 (1): 206–210. doi:10.12669/pjms.301.4072. ISSN 1681-715X. PMID 24639862. PMC 3955573. http://pjms.com.pk/index.php/pjms/article/view/4072.

- ↑ Prevention, Forum on Global Violence; Health, Board on Global; Medicine, Institute of; Council, National Research (2013-02-06), "THE CONTAGION OF SUICIDAL BEHAVIOR" (in en), Contagion of Violence: Workshop Summary (National Academies Press (US)), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207262/, retrieved 2023-11-14

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Stack, Steven (November 2021). "Contributing factors to suicide: Political, social, cultural and economic". Preventive Medicine 152 (Pt 1): 106498. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106498. ISSN 0091-7435. PMID 34538366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106498.

- ↑ "Share of deaths from suicide". https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/share-deaths-suicide.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Dattani, Saloni; Rodés-Guirao, Lucas; Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban (2023-04-02). "Suicides". Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/suicide.

- ↑ Bantjes, J.; Iemmi, V.; Coast, E.; Channer, K.; Leone, T.; McDaid, D.; Palfreyman, A.; Stephens, B. et al. (2016). "Poverty and suicide research in low- and middle-income countries: systematic mapping of literature published in English and a proposed research agenda" (in en). Global Mental Health 3: e32. doi:10.1017/gmh.2016.27. ISSN 2054-4251. PMID 28596900.

- ↑ "Stats of the State – Suicide Mortality" (in en-us). 2023-02-15. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/suicide-mortality/suicide.htm.

- ↑ "Suicide in Rural Areas – RHIhub Toolkit" (in en). https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/suicide/1/rural#:~:text=The%20suicide%20rate%20is%20nearly,100,000%20people%20in%20urban%20areas)..

- ↑ Office, U. S. Government Accountability (29 September 2022). "Why Health Care Is Harder to Access in Rural America | U.S. GAO" (in en). https://www.gao.gov/blog/why-health-care-harder-access-rural-america.

- ↑ Morales, Dawn A.; Barksdale, Crystal L.; Beckel-Mitchener, Andrea C. (October 2020). "A call to action to address rural mental health disparities" (in en). Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 4 (5): 463–467. doi:10.1017/cts.2020.42. ISSN 2059-8661. PMID 33244437.

- ↑ "Rural Areas – Suicide Prevention Resource Center" (in en-US). https://sprc.org/settings/rural-areas/.

- ↑ "Barriers to Mental Health Treatment in Rural Areas – RHIhub Toolkit" (in en). https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/mental-health/1/barriers.

- ↑ "Teen Suicide Statistics". Adolescent Teenage Suicide Prevention. FamilyFirstAid.org. 2001. http://www.familyfirstaid.org/suicide.html.

- ↑ "Referral Page – N C H S – Data Warehouse". cdc.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/datawh/statab/unpubd/mortabs.htm.

- ↑ Jodi O'Brien (Editor) (2009). Encyclopedia of Gender and Society (p. 817). SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781452266022. https://books.google.com/books?id=Lr91AwAAQBAJ&q=gender+paradox+suicidal+behavior&pg=PT869.

- ↑ "Suicide rates, crude - Data by country". WHO. 2018-04-05. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.MHSUICIDE?lang=en.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Disparities in Suicide". May 9, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/disparities-in-suicide.html.

- ↑ Hoyert, Donna; Heron, Melonie P.; Murphy, Sherry L.; Kung, Hsiang-Ching (2006-04-19). "Deaths: Final Data for 2003". National Vital Statistics Report 54 (13): 1–120. PMID 16689256. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr54/nvsr54_13.pdf. Retrieved 2006-07-22.

- ↑ "Epidemiology of Suicide", Behind Asia's Epidemic (Marten Publications), 2008

- ↑ Westefeld, John; Maples, Michael; Buford, Brian; Taylor, Steve (2001). "Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual College Students". Journal of College Student Psychotherapy 15 (3): 71–82. doi:10.1300/J035v15n03_06.

- ↑ "Sexual orientation and mental health in a birth cohort of young adults". Psychological Medicine 35 (7): 971–81. July 2005. doi:10.1017/S0033291704004222. PMID 16045064.

- ↑ "Sexual Orientation and Risk Factors for Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts Among Adolescents and Young Adults". American Journal of Public Health 97 (11): 2017–9. November 2007. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.095943. PMID 17901445.

- ↑ Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual & Transgender "Attempted Suicide" Incidences/Risks Suicidality Studies From 1970 to 2009

- ↑ Bell & Weinberg (1978): Tables 21.14 & 21.15, pages 453–454.

- ↑ "Depression, hopelessness, suicidality, and related factors in sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 67 (6): 859–66. December 1999. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.67.6.859. PMID 10596508.

- ↑ "Adolescent Sexual Orientation and Suicide Risk: Evidence From a National Study". American Journal of Public Health 91 (8): 1276–81. August 2001. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.8.1276. PMID 11499118.

- ↑ "Homosexuality. IV. Psychiatric disorders and disability in the female homosexual". The American Journal of Psychiatry 127 (2): 147–54. August 1970. doi:10.1176/ajp.127.2.147. PMID 5473144.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 ed. Sandfort, T; et al. Lesbian and Gay Studies: An Introductory, Interdisciplinary Approach. Chapter 2.

- ↑ Rotheram-Boris, et al. (1994); Proctor and Groze (1994)

- ↑ "Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults". Pediatrics 123 (1): 346–52. January 2009. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-3524. PMID 19117902.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "Risk factors for attempted suicide in gay and bisexual youth". Pediatrics 87 (6): 869–75. June 1991. doi:10.1542/peds.87.6.869. PMID 2034492. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/abstract/87/6/869.

- ↑ "Sexual orientation and suicide attempt: a longitudinal study of the general Norwegian adolescent population". Journal of Abnormal Psychology 112 (1): 144–51. February 2003. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.112.1.144. PMID 12653422.

- ↑ "The association between relationship markers of sexual orientation and suicide: Denmark, 1990–2001". Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46 (2): 111–7. December 2009. doi:10.1007/s00127-009-0177-3. PMID 20033129.

- ↑ Björkenstam, Charlotte (11 May 2016). "Suicide in married couples in Sweden: Is the risk greater in same-sex couples". European Journal of Epidemiology 31 (7): 685–690. doi:10.1007/s10654-016-0154-6. PMID 27168192.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 Norko, Michael A.; Freeman, David; Phillips, James; Hunter, William; Lewis, Richard; Viswanathan, Ramaswamy (January 2017). "Can Religion Protect Against Suicide?". Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease 205 (1): 9–14. doi:10.1097/nmd.0000000000000615. ISSN 1539-736X. PMID 27805983. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/nmd.0000000000000615.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 Gearing, Robin Edward; Alonzo, Dana (December 2018). "Religion and Suicide: New Findings" (in en). Journal of Religion and Health 57 (6): 2478–2499. doi:10.1007/s10943-018-0629-8. ISSN 0022-4197. PMID 29736876. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10943-018-0629-8.

- ↑ Zuckerman, Phil (2007). Martin, Michael. ed. The Cambridge Companion to Atheism. Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0521603676. https://archive.org/details/cambridgecompani00mart_852. "Concerning suicide rates, religious nations fare better than secular nations. According to the 2003 World Health Organization's report on international male suicides rates, of the top ten nations with the highest male suicide rates, all but one (Sri Lanka) are strongly irreligious nations with high levels of atheism. Of the top remaining nine nations leading the world in male suicide rates, all are former Soviet/Communist nations, such as Belarus, Ukraine, and Latvia. Of the bottom ten nations with the lowest male suicide rates, all are highly religious nations with statistically insignificant levels of organic atheism."

- ↑ Bertolote, Jose Manoel; Fleischmann, Alexandra (2002). "A Global Perspective in the Epidemiology of Suicide" (in en). Suicidologi 7 (2): 7–8. https://www.iasp.info/pdf/papers/Bertolote.pdf. Retrieved 2020-06-26. "In Muslim countries (e.g. Kuwait), where committing suicide is most strictly forbidden, the total suicide rate is close to zero (0.1 per 100,000 population). In Hindu (e.g. India) and Christian countries (e.g. Italy), the total suicide rate is around 10 per 100,000 (Hindu: 9.6; Christian: 11.2). In Buddhist countries (e.g. Japan), the total suicide rate is distinctly higher at 17.9 per 100,000 population. At 25.6, the total suicide rate is markedly highest in Atheist countries (e.g. China) which included in this analysis countries where religious observances had been prohibited for a long period of time (e.g. Albania).".

- ↑ E Lawrence, Ryan; A. Oquendo, Maria; Stanley, Barbara (2016). "Religion and Suicide Risk: a systematic review". Archives of Suicide Research 20 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1080/13811118.2015.1004494. PMID 26192968.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Fox, Kara; Shveda, Krystina; Croker, Natalie; Chacon, Marco (26 November 2021). "How US gun culture stacks up with the world". CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2021/11/26/world/us-gun-culture-world-comparison-intl-cmd/index.html. Article updated October 26, 2023. CNN cites data source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (Global Burden of Disease 2019), UN Population Division.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Diego De Leo & Russell Evans (Griffith University) (2003). "International Suicide Rates: Recent Trends and Implications for Australia". Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/1D2B4E895BCD429ECA2572290027094D/$File/intsui.pdf.

- ↑ Milner, Allison; Page, Andrew; LaMontagne, Anthony D. (2013-01-16). "Long-Term Unemployment and Suicide: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" (in en). PLOS ONE 8 (1): e51333. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051333. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 23341881. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...851333M.

- ↑ Ayano, Getinet; Tsegay, Light; Abraha, Mebratu; Yohannes, Kalkidan (2019-08-28). "Suicidal Ideation and Attempt among Homeless People: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Psychiatric Quarterly 90 (4): 829–842. doi:10.1007/s11126-019-09667-8. ISSN 0033-2720. PMID 31463733. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11126-019-09667-8.

- ↑ Siddique, Haroon (17 March 2017). "Male construction workers at greatest risk of suicide, study finds". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/mar/17/male-construction-workers-greatest-risk-suicide-england-study-finds.

- ↑ "Body Mass Index and Risk of Suicide Among One Million US Adults". Epidemiology 21 (1): 82–6. November 2009. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c1fa2d. PMID 19907331.

- ↑ Moitra, Modhurima; Santomauro, Damian; Degenhardt, Louisa; Collins, Pamela Y.; Whiteford, Harvey; Vos, Theo; Ferrari, Alize (2020). "Estimating the Risk of Suicide Attributable to Mental Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3732790. ISSN 1556-5068. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3732790.

- ↑ Ahmedani, Brian K.; Peterson, Edward L.; Hu, Yong; Rossom, Rebecca C.; Lynch, Frances; Lu, Christine Y.; Waitzfelder, Beth E.; Owen-Smith, Ashli A. et al. (September 2017). "Major Physical Health Conditions and Risk of Suicide" (in en). American Journal of Preventive Medicine 53 (3): 308–315. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2017.04.001. PMID 28619532.

- ↑ "Body Mass Index and Risk of Suicide Among One Million US Adults". Epidemiology 21 (1): 82–6. November 2009. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c1fa2d. PMID 19907331.

- ↑ Ottar Bjerkeset; Pål Romundstad; Jonathan Evans; David Gunnell (2008). "Association of Adult Body Mass Index and Height with Anxiety, Depression, and Suicide in the General Population". Am. J. Epidemiol. 167 (2): 193–202. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm280. PMID 17981889.

- ↑ Wagner, B (2013). "Extreme obesity is associated with suicidal behavior and suicide attempts in adults: results of a population-based representative sample". Depression and Anxiety 30 (10): 975–81. doi:10.1002/da.22105. PMID 23576272.

- ↑ Fässberg, Madeleine Mellqvist; Cheung, Gary; Canetto, Silvia Sara; Erlangsen, Annette; Lapierre, Sylvie; Lindner, Reinhard; Draper, Brian; Gallo, Joseph J. et al. (February 2016). "A systematic review of physical illness, functional disability, and suicidal behaviour among older adults" (in en). Aging & Mental Health 20 (2): 166–194. doi:10.1080/13607863.2015.1083945. ISSN 1360-7863. PMID 26381843.

- ↑ "Study: Suicides Drop During Holidays". NPR.org. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=17344747.

- ↑ "Holiday Suicides: Fact or Myth-Suicide-Violence Prevention-Injury Center-CDC". 2017-01-25. https://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/suicide/holiday.html.

- ↑ See Seasonal affective disorder

- ↑ Suicide: Practice Essentials, Overview, Etiology. 28 October 2016. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2013085-overview. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ "BBC News – HEALTH – Suicide 'linked to' the moon". http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/820241.stm.

- ↑ Woo, Jong-Min; Okusaga, Olaoluwa; Postolache, Teodor T. (February 2012). "Seasonality of suicidal behavior". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 9 (2): 531–547. doi:10.3390/ijerph9020531. ISSN 1660-4601. PMID 22470308.

- ↑ [1] NBC News article referencing a study published in Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology

- ↑ Kreitman, N. (1976). "The coal gas story. United Kingdom suicide rates, 1960–71". British Journal of Preventive and Social Medicine 30 (2): 86–93. doi:10.1136/jech.30.2.86. PMID 953381.

- ↑ Barber, Catherine W.; Miller, Matthew J. (2014-09-01). "Reducing a Suicidal Person's Access to Lethal Means of Suicide: A Research Agenda". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. Expert Recommendations for U.S. Research Priorities in Suicide Prevention 47 (3, Supplement 2): S264–S272. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.028. ISSN 0749-3797. PMID 25145749. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0749379714002475.

- ↑ Staff (February 16, 2006). "SUPRE". WHO sites: Mental Health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/supresuicideprevent/en/index.html.

- ↑ Belova, Anna; Gould, Caitlin A.; Munson, Kate; Howell, Madison; Trevisan, Claire; Obradovich, Nick; Martinich, Jeremy (2022-05-01). "Projecting the Suicide Burden of Climate Change in the United States". GeoHealth 6 (5): e2021GH000580. doi:10.1029/2021GH000580. ISSN 2471-1403. PMID 35582318. Bibcode: 2022GHeal...6..580B.

- ↑ Thomas, Kyla; Gunnell, David (1 December 2010). "Suicide in England and Wales 1861–2007: a time-trends analysis". Int J Epidemiol 39 (6): 1464–1475. doi:10.1093/ije/dyq094. PMID 20519333. https://academic.oup.com/ije/article/39/6/1464/736597/Suicide-in-England-and-Wales-1861-2007-a-time. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS - Health - More suicides under Conservative rule". 2002-09-18. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/2263690.stm.

- ↑ "Suicide during the Second World War". http://www.ww2talk.com/index.php?threads/suicide.4779/.

- ↑ Aida, Takeshi (2020-10-28). "Revisiting suicide rate during wartime: Evidence from the Sri Lankan civil war". PLOS ONE 15 (10): e0240487. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240487. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 33112885. Bibcode: 2020PLoSO..1540487A.

- ↑ Henderson, Rob (2006). "Changes in Scottish suicide rates during the Second World War". BMC Public Health 6: 167. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-167. PMID 16796751.

- ↑ Bosnar, A. (2005). "Suicide and the war in Croatia". Forensic Science International 147: S13–S16. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.09.086. PMID 15694719.

|