Astronomy:Equinox

| event | equinox | solstice | equinox | solstice | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| month | March | June | September | December | ||||

| year | day | time | day | time | day | time | day | time |

| 2019 | 20 | 21:58 | 21 | 15:54 | 23 | 07:50 | 22 | 04:19 |

| 2020 | 20 | 03:50 | 20 | 21:43 | 22 | 13:31 | 21 | 10:03 |

| 2021 | 20 | 09:37 | 21 | 03:32 | 22 | 19:21 | 21 | 15:59 |

| 2022 | 20 | 15:33 | 21 | 09:14 | 23 | 01:04 | 21 | 21:48 |

| 2023 | 20 | 21:25 | 21 | 14:58 | 23 | 06:50 | 22 | 03:28 |

| 2024 | 20 | 03:07 | 20 | 20:51 | 22 | 12:44 | 21 | 09:20 |

| 2025 | 20 | 09:02 | 21 | 02:42 | 22 | 18:20 | 21 | 15:03 |

| 2026 | 20 | 14:46 | 21 | 08:25 | 23 | 00:06 | 21 | 20:50 |

| 2027 | 20 | 20:25 | 21 | 14:11 | 23 | 06:02 | 22 | 02:43 |

| 2028 | 20 | 02:17 | 20 | 20:02 | 22 | 11:45 | 21 | 08:20 |

| 2029 | 20 | 08:01 | 21 | 01:48 | 22 | 17:37 | 21 | 14:14 |

A solar equinox is a moment in time when the Sun crosses the Earth's equator, which is to say, appears directly above the equator, rather than north or south of the equator. On the day of the equinox, the Sun appears to rise "due east" and set "due west". This occurs twice each year, around 20 March and 23 September.[lower-alpha 1]

More precisely, an equinox is traditionally defined as the time when the plane of Earth's equator passes through the geometric center of the Sun's disk.[3][4] Equivalently, this is the moment when Earth's rotation axis is directly perpendicular to the Sun-Earth line, tilting neither toward nor away from the Sun. In modern times[when?], since the Moon (and to a lesser extent the planets) causes Earth's orbit to vary slightly from a perfect ellipse, the equinox is officially defined by the Sun's more regular ecliptic longitude rather than by its declination. The instants of the equinoxes are currently defined to be when the apparent geocentric longitude of the Sun is 0° and 180°.[5]

The word is derived from the Latin aequinoctium, from aequus (equal) and nox (night). On the day of an equinox, daytime and nighttime are of approximately equal duration all over the planet. They are not exactly equal, however, because of the angular size of the Sun, atmospheric refraction, and the rapidly changing duration of the length of day that occurs at most latitudes around the equinoxes. Long before conceiving this equality, primitive equatorial cultures noted the day when the Sun rises due east and sets due west, and indeed this happens on the day closest to the astronomically defined event. As a consequence, according to a properly constructed and aligned sundial, the daytime duration is 12 hours.

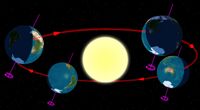

In the Northern Hemisphere, the March equinox is called the vernal or spring equinox while the September equinox is called the autumnal or fall equinox. In the Southern Hemisphere, the reverse is true. During the year, equinoxes alternate with solstices. Leap years and other factors cause the dates of both events to vary slightly.[6]

Hemisphere-neutral names are northward equinox for the March equinox, indicating that at that moment the solar declination is crossing the celestial equator in a northward direction, and southward equinox for the September equinox, indicating that at that moment the solar declination is crossing the celestial equator in a southward direction.

Equinoxes on Earth

General

Systematically observing the sunrise, people discovered that it occurs between two extreme locations at the horizon and eventually noted the midpoint between the two. Later it was realized that this happens on a day when the duration of the day and the night are practically equal and the word "equinox" comes from Latin aequus, meaning "equal", and nox, meaning "night".

In the northern hemisphere, the vernal equinox (March) conventionally marks the beginning of spring in most cultures and is considered the start of the New Year in the Assyrian calendar, Hindu, and the Persian or Iranian calendars,[lower-alpha 2] while the autumnal equinox (September) marks the beginning of autumn.[7] Ancient Greek calendars too had the beginning of the year either at the autumnal or vernal equinox and some at solstices. The Antikythera mechanism predicts the equinoxes and solstices.[8]

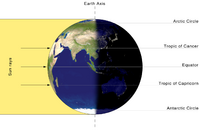

The relation between the Earth, Sun, and stars at the March equinox. From Earth's perspective, the Sun appears to move along the ecliptic (red), which is tilted compared to the celestial equator (white).

Diagram of the Earth's seasons as seen from the north. Far right: December solstice.

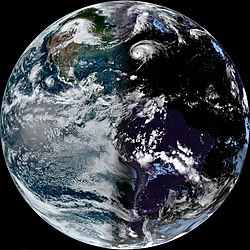

The equinoxes are the only times when the solar terminator (the "edge" between night and day) is perpendicular to the equator. As a result, the northern and southern hemispheres are equally illuminated.

For the same reason, this is also the time when the Sun rises for an observer at one of Earth's rotational poles and sets at the other. For a brief period lasting approximately four days, both North and South Poles are in daylight.[lower-alpha 3] For example, in 2021 sunrise on the North Pole is 18 March 07:09 UTC, and sunset on the South Pole is 22 March 13:08 UTC. Also in 2021, sunrise on the South Pole is 20 September 16:08 UTC, and sunset on the North Pole is 24 September 22:30 UTC.[9][10]

In other words, the equinoxes are the only times when the subsolar point is on the equator, meaning that the Sun is exactly overhead at a point on the equatorial line. The subsolar point crosses the equator moving northward at the March equinox and southward at the September equinox.

Date

When Julius Caesar established the Julian calendar in 45 BC, he set 25 March as the date of the spring equinox;[11] this was already the starting day of the year in the Persian and Indian calendars. Because the Julian year is longer than the tropical year by about 11.3 minutes on average (or 1 day in 128 years), the calendar "drifted" with respect to the two equinoxes – so that in 300 AD the spring equinox occurred on about 21 March, and by the 1580s AD it had drifted backwards to 11 March.[12]

This drift induced Pope Gregory XIII to establish the modern Gregorian calendar. The Pope wanted to continue to conform with the edicts of the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD concerning the date of Easter, which means he wanted to move the vernal equinox to the date on which it fell at that time (21 March is the day allocated to it in the Easter table of the Julian calendar), and to maintain it at around that date in the future, which he achieved by reducing the number of leap years from 100 to 97 every 400 years. However, there remained a small residual variation in the date and time of the vernal equinox of about ±27 hours from its mean position, virtually all because the distribution of 24 hour centurial leap-days causes large jumps (see Gregorian calendar leap solstice).

Modern dates

The dates of the equinoxes change progressively during the leap-year cycle, because the Gregorian calendar year is not commensurate with the period of the Earth's revolution about the Sun. It is only after a complete Gregorian leap-year cycle of 400 years that the seasons commence at approximately the same time. In the 21st century the earliest March equinox will be 19 March 2096, while the latest was 21 March 2003. The earliest September equinox will be 21 September 2096 while the latest was 23 September 2003 (Universal Time).[6]

Names

- Vernal equinox and autumnal equinox: these classical names are direct derivatives of Latin (ver = spring, and autumnus = autumn). These are the historically universal and still most widely used terms for the equinoxes, but are potentially confusing because in the southern hemisphere the vernal equinox does not occur in spring and the autumnal equinox does not occur in autumn. The equivalent common language English terms spring equinox and autumn (or fall) equinox are even more ambiguous.[13][14][15] It has become increasingly common for people to refer to the September equinox in the southern hemisphere as the Vernal equinox.[16][17]

- March equinox and September equinox: names referring to the months of the year in which they occur, with no ambiguity as to which hemisphere is the context. They are still not universal, however, as not all cultures use a solar-based calendar where the equinoxes occur every year in the same month (as they do not in the Islamic calendar and Hebrew calendar, for example).[18] Although the terms have become very common in the 21st century, they were sometimes used at least as long ago as the mid-20th century.[19]

- Northward equinox and southward equinox: names referring to the apparent direction of motion of the Sun. The northward equinox occurs in March when the Sun crosses the equator from south to north, and the southward equinox occurs in September when the Sun crosses the equator from north to south. These terms can be used unambiguously for other planets. They are rarely seen, although were first proposed over 100 years ago.[20]

- First point of Aries and first point of Libra: names referring to the astrological signs the Sun is entering. However, the precession of the equinoxes has shifted these points into the constellations Pisces and Virgo, respectively.[21]

Length of equinoctial day and night

On the date of the equinox, the center of the Sun spends a roughly equal amount of time above and below the horizon at every location on the Earth, so night and day[lower-alpha 4] are about the same length. Sunrise and sunset can be defined in several ways, but a widespread definition is the time that the top limb of the Sun is level with the horizon.[22] With this definition, the day is longer than the night at the equinoxes:[3]

- From the Earth, the Sun appears as a disc rather than a point of light, so when the centre of the Sun is below the horizon, its upper edge may be visible. Sunrise, which begins daytime, occurs when the top of the Sun's disk appears above the eastern horizon. At that instant, the disk's centre is still below the horizon.

- The Earth's atmosphere refracts sunlight. As a result, an observer sees daylight before the top of the Sun's disk appears above the horizon.

In sunrise/sunset tables, the atmospheric refraction is assumed to be 34 arcminutes, and the assumed semidiameter (apparent radius) of the Sun is 16 arcminutes. (The apparent radius varies slightly depending on time of year, slightly larger at perihelion in January than aphelion in July, but the difference is comparatively small.) Their combination means that when the upper limb of the Sun is on the visible horizon, its centre is 50 arcminutes below the geometric horizon, which is the intersection with the celestial sphere of a horizontal plane through the eye of the observer.[23]

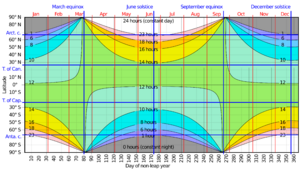

These effects make the day about 14 minutes longer than the night at the equator and longer still towards the poles. The real equality of day and night only happens in places far enough from the equator to have a seasonal difference in day length of at least 7 minutes,[24] actually occurring a few days towards the winter side of each equinox.

The times of sunset and sunrise vary with the observer's location (longitude and latitude), so the dates when day and night are equal also depend upon the observer's location.

A third correction for the visual observation of a sunrise (or sunset) is the angle between the apparent horizon as seen by an observer and the geometric (or sensible) horizon. This is known as the dip of the horizon and varies from 3 arcminutes for a viewer standing on the sea shore to 160 arcminutes for a mountaineer on Everest.[25] The effect of a larger dip on taller objects (reaching over 2½° of arc on Everest) accounts for the phenomenon of snow on a mountain peak turning gold in the sunlight long before the lower slopes are illuminated.

The date on which the day and night are exactly the same is known as an equilux; the neologism, believed to have been coined in the 1980s, achieved more widespread recognition in the 21st century.[lower-alpha 5] At the most precise measurements, a true equilux is rare, because the lengths of day and night change more rapidly than any other time of the year around the equinoxes. In the mid-latitudes, daylight increases or decreases by about three minutes per day at the equinoxes, and thus adjacent days and nights only reach within one minute of each other. The date of the closest approximation of the equilux varies slightly by latitude; in the mid-latitudes, it occurs a few days before the spring equinox and after the fall equinox in each respective hemisphere.

Geocentric view of the astronomical seasons

In the half-year centered on the June solstice, the Sun rises north of east and sets north of west, which means longer days with shorter nights for the northern hemisphere and shorter days with longer nights for the southern hemisphere. In the half-year centered on the December solstice, the Sun rises south of east and sets south of west and the durations of day and night are reversed.

Also on the day of an equinox, the Sun rises everywhere on Earth (except at the poles) at about 06:00 and sets at about 18:00 (local solar time). These times are not exact for several reasons:

- Most places on Earth use a time zone which differs from the local solar time by minutes or even hours. For example, if a location uses a time zone with reference meridian 15° to the east, the Sun will rise around 07:00 on the equinox and set 12 hours later around 19:00 .

- Day length is also affected by the variable orbital speed of the Earth around the Sun. This combined effect is described as the equation of time. Thus even locations which lie on their time zone's reference meridian will not see sunrise and sunset at 6:00 and 18:00 . At the March equinox they are 7–8 minutes later, and at the September equinox they are about 7–8 minutes earlier.

- Sunrise and sunset are commonly defined for the upper limb of the solar disk, rather than its center. The upper limb is already up for at least a minute before the center appears, and the upper limb likewise sets later than the center of the solar disk. Also, when the Sun is near the horizon, atmospheric refraction shifts its apparent position above its true position by a little more than its own diameter. This makes sunrise more than two minutes earlier and sunset an equal amount later. These two effects combine to make the equinox day 12h 7m long and the night only 11h 53m. Note, however, that these numbers are only true for the tropics. For moderate latitudes, the discrepancy increases (e.g., 12 minutes in London); and closer to the poles it becomes very much larger (in terms of time). Up to about 100 km from either pole, the Sun is up for a full 24 hours on an equinox day.

- Height of the horizon changes the day's length. For an observer atop a mountain the day is longer, while standing in a valley will shorten the day.

- The Sun is larger in diameter than the Earth, so more than half of the Earth is in sunlight at any one time (because non-parallel rays create tangent points beyond an equal-day-night line).

Day arcs of the Sun

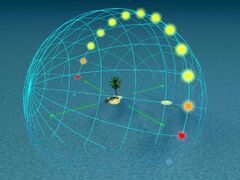

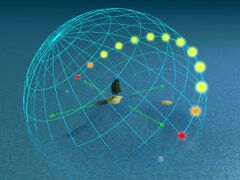

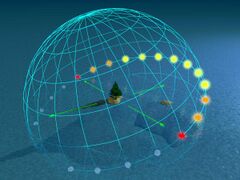

Some of the statements above can be made clearer by picturing the day arc (i.e., the path along which the Sun appears to move across the sky). The pictures show this for every hour on equinox day. In addition, some 'ghost' suns are also indicated below the horizon, up to 18° below it; the Sun in such areas still causes twilight. The depictions presented below can be used for both the northern and the southern hemispheres. The observer is understood to be sitting near the tree on the island depicted in the middle of the ocean; the green arrows give cardinal directions.

- In the northern hemisphere, north is to the left, the Sun rises in the east (far arrow), culminates in the south (right arrow), while moving to the right and setting in the west (near arrow).

- In the southern hemisphere, south is to the left, the Sun rises in the east (near arrow), culminates in the north (right arrow), while moving to the left and setting in the west (far arrow).

The following special cases are depicted:

Celestial coordinate systems

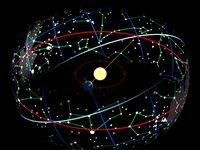

The March equinox occurs about when the Sun appears to cross the celestial equator northward. In the Northern Hemisphere, the term vernal point is used for the time of this occurrence and for the precise direction in space where the Sun exists at that time. This point is the origin of some celestial coordinate systems, which are usually rooted to an astronomical epoch since it gradually varies (precesses) over time:

- in the ecliptic coordinate system, the vernal point is the origin of the ecliptic longitude;

- in the equatorial coordinate system, the vernal point is the origin of the right ascension.

The modern definition of equinox is the instant when the Sun's apparent geocentric ecliptic longitude is 0° (northward equinox) or 180° (southward equinox).[30][31][32] Note that at that moment, its latitude will not be exactly zero, since Earth is not exactly in the plane of the ecliptic. Its declination will also not be exactly zero, so the scientific definition is slightly different from the traditional one. The mean ecliptic is defined by the barycenter of Earth and the Moon combined, to minimize the fact that the orbital inclination of the Moon causes the Earth to wander slightly above and below the ecliptic.[34] See the adjacent diagram.

Because of the precession of the Earth's axis, the position of the vernal point on the celestial sphere changes over time, and the equatorial and the ecliptic coordinate systems change accordingly. Thus when specifying celestial coordinates for an object, one has to specify at what time the vernal point and the celestial equator are taken. That reference time can either be a conventional time (like J2000), or an arbitrary point in time, as for the equinox of date.[35]

The upper culmination of the vernal point is considered the start of the sidereal day for the observer. The hour angle of the vernal point is, by definition, the observer's sidereal time.

Using the current official IAU constellation boundaries – and taking into account the variable precession speed and the rotation of the celestial equator – the equinoxes shift through the constellations as follows[36] (expressed in astronomical year numbering when the year 0 = 1 BC, −1 = 2 BC, etc.):

- The March equinox passed from Taurus into Aries in year −1865, passed into Pisces in year −67, will pass into Aquarius in year 2597, and then into Capricornus in year 4312. In 1489 it came within 10 arcminutes of Cetus without crossing the boundary.

- The September equinox passed from Libra into Virgo in year −729, will pass into Leo in year 2439.

Auroras

Mirror-image conjugate auroras have been observed during the equinoxes.[37]

Cultural aspects

The equinoxes are sometimes regarded as the start of spring and autumn. A number of traditional harvest festivals are celebrated on the date of the equinoxes.

Religious architecture is often determined by the equinox; the Angkor Wat Equinox during which the sun rises in a perfect alignment over Angkor Wat in Cambodia is one such example.[38]

Catholic churches, since the recommendations of Charles Borromeo, have often chosen the equinox as their reference point for the orientation of churches.[39]

Effects on satellites

One effect of equinoctial periods is the temporary disruption of communications satellites. For all geostationary satellites, there are a few days around the equinox when the Sun goes directly behind the satellite relative to Earth (i.e. within the beam-width of the ground-station antenna) for a short period each day. The Sun's immense power and broad radiation spectrum overload the Earth station's reception circuits with noise and, depending on antenna size and other factors, temporarily disrupt or degrade the circuit. The duration of those effects varies but can range from a few minutes to an hour. (For a given frequency band, a larger antenna has a narrower beam-width and hence experiences shorter duration "Sun outage" windows.)[40]

Satellites in geostationary orbit also experience difficulties maintaining power during the equinox because they have to travel through Earth's shadow and rely only on battery power. Usually, a satellite travels either north or south of the Earth's shadow because Earth's axis is not directly perpendicular to a line from the Earth to the Sun at other times. During the equinox, since geostationary satellites are situated above the Equator, they are in Earth's shadow for the longest duration all year.[41]

Equinoxes on other planets

Equinoxes are defined on any planet with a tilted rotational axis. A dramatic example is Saturn, where the equinox places its ring system edge-on facing the Sun. As a result, they are visible only as a thin line when seen from Earth. When seen from above – a view seen during an equinox for the first time from the Cassini space probe in 2009 – they receive very little sunshine; indeed, they receive more planetshine than light from the Sun.[42] This phenomenon occurs once every 14.7 years on average, and can last a few weeks before and after the exact equinox. Saturn's most recent equinox was on 11 August 2009, and its next will take place on 6 May 2025.[43]

Mars's most recent equinoxes were on 24 February 2022 (northern autumn), and on 26 December 2022 (northern spring).[44]

See also

- Analemma

- Anjana (Cantabrian mythology) – fairies believed to appear on the spring equinox

- Angkor Wat Equinox

- Aphelion – occurs around 5 July (see formula)

- Geocentric view of the seasons

- Iranian calendars

- Kōreisai – days of worship in Japan that began in 1878

- Lady Day

- Nowruz

- Orientation of churches

- Perihelion and aphelion

- Solstice

- Songkran

- Sun outage – a satellite phenomenon that occurs around the time of an equinox

- Tekufah

- Wheel of the Year

- Zoroastrian calendar

Footnotes

- ↑ This article follows the customary Wikipedia style detailed at Manual of Style/Dates and numbers#Julian and Gregorian calendars; dates before 15 October 1582 are given in the Julian calendar while more recent dates are given in the Gregorian calendar. Dates before 1 March 8 AD are given in the Julian calendar as observed in Rome; there is an uncertainty of a few days when these early dates are converted to the proleptic Julian calendar.

- ↑ The year in the Iranian calendar begins on Nowruz, which means "new day".

- ↑ This is possible because atmospheric refraction "lofts" the Sun's apparent disk above its true position in the sky.

- ↑ Here, "day" refers to when the Sun is above the horizon.

- ↑ Prior to the 1980s there was no generally accepted term for the phenomenon, and the word "equilux" was more commonly used as a synonym for isophot.[26] The newer meaning of "equilux" is modern (c. 1985 to 1986), and not usually intended: Technical references since the beginning of the 20th century (c. 1910) have used the terms "equilux" and "isophot" interchangeably to mean "of equal illumination" in the context of curves showing how intensely lighting equipment will illuminate a surface. See for instance Walsh (1947).[27] The earliest confirmed use of the modern meaning was in a post on the Usenet group net.astro,[28] which refers to "discussion last year exploring the reasons why equilux and equinox are not coincident". Use of this particular pseudo-latin protologism can only be traced to an extremely small (less than six) number of predominently U.S. American people in such online media for the next 20 years until its broader adoption as a neologism (c. 2006), and then its subsequent use by more mainstream organisations (c. 2012).[29]

References

- ↑ United States Naval Observatory (January 4, 2018). "Earth's Seasons and Apsides: Equinoxes, Solstices, Perihelion, and Aphelion". http://aa.usno.navy.mil/data/docs/EarthSeasons.php. [|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "Solstices and Equinoxes: 2001 to 2100". February 20, 2018. http://www.astropixels.com/ephemeris/soleq2001.html.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Equinoxes". Astronomical Information Center. United States Naval Observatory. 14 June 2019. https://aa.usno.navy.mil/faq/docs/equinoxes.php. "On the day of an equinox, the geometric center of the Sun's disk crosses the equator, and this point is above the horizon for 12 hours everywhere on the Earth. However, the Sun is not simply a geometric point. Sunrise is defined as the instant when the leading edge of the Sun's disk becomes visible on the horizon, whereas sunset is the instant when the trailing edge of the disk disappears below the horizon. These are the moments of first and last direct sunlight. At these times the center of the disk is below the horizon. Furthermore, atmospheric refraction causes the Sun's disk to appear higher in the sky than it would if the Earth had no atmosphere. Thus, in the morning the upper edge of the disk is visible for several minutes before the geometric edge of the disk reaches the horizon. Similarly, in the evening the upper edge of the disk disappears several minutes after the geometric disk has passed below the horizon. The times of sunrise and sunset in almanacs are calculated for the normal atmospheric refraction of 34 minutes of arc and a semidiameter of 16 minutes of arc for the disk. Therefore, at the tabulated time the geometric center of the Sun is actually 50 minutes of arc below a regular and unobstructed horizon for an observer on the surface of the Earth in a level region"

- ↑ "ESRL Global Monitoring Division - Global Radiation Group" (in EN-US). U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/grad/solcalc/glossary.html#equinox.

- ↑ Astronomical Almanac. United States Naval Observatory. 2008. Glossary.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Yallop, B.D.; Hohenkerk, C.Y.; Bell, S.A. (2013). "Astronomical Phenomena". in Urban, S.E.; Seidelmann, P. K.. Explanatory supplement to the astronomical almanac (3rd ed.). Mill Valley, CA: University Science Books. pp. 506–507. ISBN 978-1-891389-85-6.

- ↑ "March Equinox – Equal Day and Night, Nearly" (in en). 2017. https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/march-equinox.html.

- ↑ Freeth, T., Bitsakis, Y., Moussas, X., Seiradakis, J. H., Tselikas, A., Mangou, H., ... & Allen, M. (2006). Decoding the ancient Greek astronomical calculator known as the Antikythera Mechanism. Nature, 444(7119), 587-591.

- ↑ Sunrise and sunset times in 90°00'N, 0°00'E (North Pole), timeanddate.com

- ↑ Sunrise and sunset times in 90°00'S, 0°00'E (South Pole), timeanddate.com

- ↑ Blackburn, Bonnie J.; Holford-Strevens, Leofranc (1999). The Oxford companion to the year. Oxford University Press. p. 135. ISBN 0-19-214231-3. Reprinted with corrections 2003.

- ↑ Richards, E. G. (1998). Mapping Time: The Calendar and its History. Oxford University Press. pp. 250–251. ISBN 978-0192862051.

- ↑ Skye, Michelle (2007). Goddess Alive!: Inviting Celtic & Norse Goddesses Into Your Life. Llewellyn Worldwide. pp. 69ff. ISBN 978-0-7387-1080-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=s1x2ATL66UcC&pg=PT69.

- ↑ Curtis, Howard D. (2013). Orbital Mechanics for Engineering Students. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 188ff. ISBN 978-0-08-097748-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=2U9Z8k0TlTYC&pg=PA188.

- ↑ Grewal, Mohinder S.; Weill, Lawrence R.; Andrews, Angus P. (2007). Global Positioning Systems, Inertial Navigation, and Integration. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 459ff. ISBN 978-0-470-09971-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=6P7UNphJ1z8C&pg=PA459.

- ↑ Bowditch, Nathaniel (2002). The American practical navigator: An epitome of navigation. Paradise Cay Publications. pp. 229ff. ISBN 978-0-939837-54-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=pXjHDnIE_ygC&pg=PA229.

- ↑ Exploring the Earth. Allied Publishers. 2016. pp. 31ff. ISBN 978-81-8424-408-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=hs-PBSZTCBMC&pg=PT31.

- ↑ La Rocque, Paula (2007). On Words: Insights into how our words work – and don't. Marion Street Press. pp. 89ff. ISBN 978-1-933338-20-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=7VPSb8py5jUC&pg=PA89.

- ↑ Popular Astronomy. 1945. https://books.google.com/books?id=CcEzAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ Notes and Queries. Oxford University Press. 1895. https://archive.org/details/notesandqueries06whitgoog.

- ↑ Spherical Astronomy. Krishna Prakashan Media. pp. 233ff. GGKEY:RDRHQ35FBX7. https://books.google.com/books?id=9KFRhcsn8-UC&pg=PA233.

- ↑ Forsythe, William C.; Rykiel, Edward J.; Stahl, Randal S.; Wu, Hsin-i; Schoolfield, Robert M. (1995). "A model comparison for day length as a function of latitude and day of year". Ecological Modelling 80: 87–95. doi:10.1016/0304-3800(94)00034-F. https://www.ikhebeenvraag.be/mediastorage/FSDocument/171/Forsythe+-+A+model+comparison+for+daylength+as+a+function+of+latitude+and+day+of+year+-+1995.pdf.

- ↑ Seidelman, P. Kenneth, ed (1992). Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac. Mill Valley, CA: University Science Books. p. 32. ISBN 0-935702-68-7.

- ↑ "Sunrise and Sunset". 21 October 2002. http://www.cso.caltech.edu/outreach/log/NIGHT_DAY/sunrise.htm.

- ↑ Biegert, Mark (21 October 2015). "Correcting Sextant Measurements for Dip". Math Encounters (blog). http://mathscinotes.com/2015/10/correcting-sextant-measurements-for-dip/.

- ↑ Owens, Steve (20 March 2010). "Equinox, Equilux, and Twilight Times". Dark Sky Diary (blog). http://darkskydiary.wordpress.com/2010/03/20/equinox-equilux-and-twilight-times/.

- ↑ Walsh, John William Tudor (1947). Textbook of Illuminating Engineering (Intermediate Grade). I. Pitman. https://books.google.com/books?id=iC46AAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ "Spring Equilux Approaches". 14 March 1986. https://groups.google.com/forum/#!original/net.astro/u1ufhWfdA00/eGRinwb18n0J.

- ↑ "The Equinox and Solstice". U.K. Meteorological Office. https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/weather/learn-about/weather/seasons/equinox-and-solstice.

- ↑ Astronomical Almanac 2008. United States Naval Observatory. 2006. Glossary Chapter.

- ↑ Meeus, Jean (1997). Mathematical Astronomy Morsels.

- ↑ Meeus, Jean (1998). Astronomical Algorithms (Second ed.).

- ↑ Hilton, James L.; McCarthy, Dennis D. (2013). "Precession, Nutation, Polar Motion, and Earth Rotation". in Urban, S.E.; Seidelmann, P.K.. Explanatory supplement to the astronomical almanac (3rd ed.). Mill Valley, CA: University Science Books. pp. 205–206. ISBN 978-1-891389-85-6.

- ↑ "The IAU Working Group on Precession and the Ecliptic...have recommended that the ecliptic be more precisely defined as the plane perpendicular to the mean orbital angular momentum vector of the Earth-Moon barycenter passing through the Sun in the BCRS." [Internal citations omitted.][33]

- ↑ Montenbruck, Oliver; Pfleger, Thomas (1994). Astronomy on the Personal Computer. Springer-Verlag. p. 17. ISBN 0-387-57700-9. https://archive.org/details/astronomyonperso00mont.

- ↑ Meeus, J. (1997). Mathematical Astronomical Morsels. ISBN 0-943396-51-4.

- ↑ Davis, Neil (1992). The Aurora Watcher's Handbook. University of Alaska Press. pp. 117–124. ISBN 0-912006-60-9.

- ↑ DiBiasio, Jame (2013-07-15) (in en). The Story of Angkor. Silkworm Books. ISBN 978-1-63102-259-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=fg4LBAAAQBAJ&dq=angkor+equinox&pg=PT37.

- ↑ Johnson, Walter (2011-11-18) (in en). Byways in British Archaeology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22877-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=MZQeHSDPe0MC&dq=equinox+as+their+reference+point+for+the+orientation+of+churches.&pg=PA229.

- ↑ "Satellite Sun Interference" (in en-US). http://www.intelsat.com/tools-resources/library/satellite-101/satellite-sun-interference/.

- ↑ Miller, Alex (17 April 2018). "How satellites are affected by the spring and autumn equinoxes" (in en-US). https://corpblog.viasat.com/how-satellites-are-affected-by-the-spring-and-autumn-equinoxes/.

- ↑ "PIA11667: The Rite of Spring". Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA11667.

- ↑ Lakdawalla, Emily (7 July 2016). "Oppositions, conjunctions, seasons, and ring plane crossings of the giant planets". http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2016/06031044-oppositions-conjunctions-rpx.html.

- ↑ "Mars Calendar". The Planetary Society. http://www.planetary.org/explore/space-topics/mars/mars-calendar.html.

External links

- "Day and Night World Map (night and day map on equinox)". http://www.timeanddate.com/worldclock/sunearth.html?iso=20150923T0820.

- "Calculation of Length of Day (Formulas and Graphs)". http://www.gandraxa.com/length_of_day.xml.

- "Equinoctial Points". http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/1/2/3/4/12342/12342-h/12342-h.htm#E.

- "Table of times of spring Equinox for a thousand years: 1452–2547". http://nshdpi.ca/is/equinox/eqindex.html.

- Gray, Meghan; Merrifield, Michael. "Solstice and Equinox". in Haran, Brady. University of Nottingham. http://www.sixtysymbols.com/videos/solstice.htm.

|