Biology:Biomolecular condensate

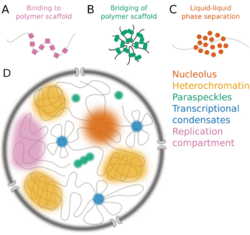

In biochemistry, biomolecular condensates are a class of membrane-less organelles and organelle subdomains, which carry out specialized functions within the cell. Unlike many organelles, biomolecular condensate composition is not controlled by a bounding membrane. Instead, condensates can form and maintain organization through a range of different processes, the most well-known of which is phase separation of proteins, RNA and other biopolymers into either colloidal emulsions, gels, liquid crystals, solid crystals or aggregates within cells.[1]

History

Micellar theory

The micellar theory of Carl Nägeli was developed from his detailed study of starch granules in 1858.[2] Amorphous substances such as starch and cellulose were proposed to consist of building blocks, packed in a loosely crystalline array to form what he later termed “micelles”. Water could penetrate between the micelles, and new micelles could form in the interstices between old micelles. The swelling of starch grains and their growth was described by a molecular-aggregate model, which he also applied to the cellulose of the plant cell wall. The modern usage of 'micelle' refers strictly to lipids, but its original usage clearly extended to other types of biomolecule, and this legacy is reflected to this day in the description of milk as being composed of 'casein micelles'.

Colloidal phase separation theory

File:Parasite130059-fig7 Spermiogenesis in Pleurogenidae (Digenea).tif

The concept of intracellular colloids as an organizing principle for the compartmentalization of living cells dates back to the end of the 19th century, beginning with William Bate Hardy and Edmund Beecher Wilson who described the cytoplasm (then called 'protoplasm') as a colloid.[3][4] Around the same time, Thomas Harrison Montgomery Jr. described the morphology of the nucleolus, an organelle within the nucleus, which has subsequently been shown to form through intracellular phase separation.[5] WB Hardy linked formation of biological colloids with phase separation in his study of globulins, stating that: "The globulin is dispersed in the solvent as particles which are the colloid particles and which are so large as to form an internal phase",[6] and further contributed to the basic physical description of oil-water phase separation.[7]

Colloidal phase separation as a driving force in cellular organisation appealed strongly to Stephane Leduc, who wrote in his influential 1911 book The Mechanism of Life: "Hence the study of life may be best begun by the study of those physico-chemical phenomena which result from the contact of two different liquids. Biology is thus but a branch of the physico-chemistry of liquids; it includes the study of electrolytic and colloidal solutions, and of the molecular forces brought into play by solution, osmosis, diffusion, cohesion, and crystallization."[8]

The primordial soup theory of the origin of life, proposed by Alexander Oparin in Russian in 1924 (published in English in 1936)[9] and by J.B.S. Haldane in 1929,[10] suggested that life was preceded by the formation of what Haldane called a "hot dilute soup" of "colloidal organic substances", and which Oparin referred to as 'coacervates' (after de Jong[11]) – particles composed of two or more colloids which might be protein, lipid or nucleic acid. These ideas strongly influenced the subsequent work of Sidney W. Fox on proteinoid microspheres.

Support from other disciplines

When cell biologists largely abandoned colloidal phase separation, it was left to relative outsiders – agricultural scientists and physicists – to make further progress in the study of phase separating biomolecules in cells.

Beginning in the early 1970s, Harold M Farrell Jr. at the US Department of Agriculture developed a colloidal phase separation model for milk casein micelles that form within mammary gland cells before secretion as milk.[12]

Also in the 1970s, physicists Tanaka & Benedek at MIT identified phase-separation behaviour of gamma-crystallin proteins from lens epithelial cells and cataracts in solution,[13][14][15][16][17] which Benedek referred to as 'protein condensation'.[18]

In the 1980s and 1990s, Athene Donald's polymer physics lab in Cambridge extensively characterised phase transitions / phase separation of starch granules from the cytoplasm of plant cells, which behave as liquid crystals.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26]

In 1991, Pierre-Gilles de Gennes received the Nobel Prize in Physics for developing a generalized theory of phase transitions with particular applications to describing ordering and phase transitions in polymers.[27] Unfortunately, de Gennes wrote in Nature that polymers should be distinguished from other types of colloids, even though they can display similar clustering and phase separation behaviour,[28] a stance that has been reflected in the reduced usage of the term colloid to describe the higher-order association behaviour of biopolymers in modern cell biology and molecular self-assembly.

Phase separation revisited

Advances in confocal microscopy at the end of the 20th century identified proteins, RNA or carbohydrates localising to many non-membrane bound cellular compartments within the cytoplasm or nucleus which were variously referred to as 'puncta/dots',[29][30][31][32] 'signalosomes',[33][34] 'granules',[35] 'bodies', 'assemblies',[32] 'paraspeckles', 'purinosomes',[36] 'inclusions', 'aggregates' or 'factories'. During this time period (1995-2008) the concept of phase separation was re-borrowed from colloidal chemistry & polymer physics and proposed to underlie both cytoplasmic and nuclear compartmentalization.[37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46]

Since 2009, further evidence for biomacromolecules undergoing intracellular phase transitions (phase separation) has been observed in many different contexts, both within cells and in reconstituted in vitro experiments.[47][48][49][50][51][52][53]

The newly coined term "biomolecular condensate"[54] refers to biological polymers (as opposed to synthetic polymers) that undergo self assembly via clustering to increase the local concentration of the assembling components, and is analogous to the physical definition of condensation.[55][54]

In physics, condensation typically refers to a gas–liquid phase transition.

In biology the term 'condensation' is used much more broadly and can also refer to liquid–liquid phase separation to form colloidal emulsions or liquid crystals within cells, and liquid–solid phase separation to form gels,[1] sols, or suspensions within cells as well as liquid-to-solid phase transitions such as DNA condensation during prophase of the cell cycle or protein condensation of crystallins in cataracts.[18] With this in mind, the term 'biomolecular condensates' was deliberately introduced to reflect this breadth (see below). Since biomolecular condensation generally involves oligomeric or polymeric interactions between an indefinite number of components, it is generally considered distinct from formation of smaller stoichiometric protein complexes with defined numbers of subunits, such as viral capsids or the proteasome – although both are examples of spontaneous molecular self-assembly or self-organisation.

Mechanistically, it appears that the conformational landscape[56] (in particular, whether it is enriched in extended disordered states) and multivalent interactions between intrinsically disordered proteins (including cross-beta polymerisation),[57] and/or protein domains that induce head-to-tail oligomeric or polymeric clustering,[58] might play a role in phase separation of proteins.

Examples

Many examples of biomolecular condensates have been characterized in the cytoplasm and the nucleus that are thought to arise by either liquid–liquid or liquid–solid phase separation.

Cytoplasmic condensates

- Lewy bodies

- Stress granule

- P-body

- Germline P-granules – oskar

- Starch granules

- Glycogen granules[59]

- Frodosomes (Dact1)[60]

- Corneal lens formation and cataracts[13][14][15][16][17][18]

- Other cytoplasmic inclusions such as pigment granules or cytoplasmic crystals

- Purinosomes[36]

- Misfolded protein aggregation such as amyloid fibrils or mutant Haemoglobin S (HbS) fibres in sickle cell disease

- Signalosomes, such as the supramolecular assemblies in the Wnt signaling pathway.[61][62]

- It can also be argued that cytoskeletal filaments form by a polymerisation process similar to phase separation, except ordered into filamentous networks instead of amorphous droplets or granules.

- Bacteria Ribonucleoprotein Bodies (BR-bodies)- In recent studies it has been shown that bacteria RNA degradosomes can assemble into phase‐separated structures, termed bacterial ribonucleoprotein bodies (BR‐bodies), with many analogous properties to eukaryotic processing bodies and stress granules.[63]

- FLOE1 granules: FLOE1 is a prion-like seed-specific protein that controls plant seed germination via phase separation into biomolecular condensates.[64]

Nuclear condensates

Other nuclear structures including heterochromatin form by mechanisms similar to phase separation, so can also be classified as biomolecular condensates.

Plasma membrane associated condensates

- Membrane protein, or membrane-associated protein, clustering at neurological synapses, cell-cell tight junctions, or other membrane domains.[65]

Secreted extracellular condensates

- Secreted thyroglobulin colloid and colloid nodules of the thyroid gland

- Secreted casein ‘micelles’ of the mammary gland

- Serum albumin and globulins

- Secreted lysozyme[66][42]

Lipid-enclosed organelles and lipoproteins are not considered condensates

Typical organelles or endosomes enclosed by a lipid bilayer are not considered biomolecular condensates. In addition, lipid droplets are surrounded by a lipid monolayer in the cytoplasm, or in milk, or in tears,[67] so appear to fall under the 'membrane bound' category. Finally, secreted LDL and HDL lipoprotein particles are also enclosed by a lipid monolayer. The formation of these structures involves phase separation to from colloidal micelles or liquid crystal bilayers, but they are not classified as biomolecular condensates, as this term is reserved for non-membrane bound organelles.

Liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) in biology

Liquid biomolecular condensates

Liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) generates a subtype of colloid known as an emulsion that can coalesce to from large droplets within a liquid. Ordering of molecules during liquid–liquid phase separation can generate liquid crystals rather than emulsions. In cells, LLPS produces a liquid subclass of biomolecular condensate that can behave as either an emulsion or liquid crystal.

The term biomolecular condensates was introduced in the context of intracellular assemblies as a convenient and non-exclusionary term to describe non-stoichiometric assemblies of biomolecules.[54] The choice of language here is specific and important. It has been proposed that many biomolecular condensates form through liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) to form colloidal emulsions or liquid crystals in living organisms, as opposed to liquid–solid phase separation to form crystals/aggregates in gels,[1] sols or suspensions within cells or extracellular secretions.[68] However, unequivocally demonstrating that a cellular body forms through liquid–liquid phase separation is challenging,[69][47][70][71] because different material states (liquid vs. gel vs. solid) are not always easy to distinguish in living cells.[72][73] The term "biomolecular condensate" directly addresses this challenge by making no assumption regarding either the physical mechanism through which assembly is achieved, nor the material state of the resulting assembly. Consequently, cellular bodies that form through liquid–liquid phase separation are a subset of biomolecular condensates, as are those where the physical origins of assembly are unknown. Historically, many cellular non-membrane bound compartments identified microscopically fall under the broad umbrella of biomolecular condensates.

In physics, phase separation can be classified into the following types of colloid, of which biomolecular condensates are one example:

| Medium/phase | Dispersed phase | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas | Liquid | Solid | ||

| Dispersion medium |

Gas | No such colloids are known. Helium and xenon are known to be immiscible under certain conditions.[74][75] |

Liquid aerosol Examples: fog, clouds, condensation, mist, hair sprays |

Solid aerosol Examples: smoke, ice cloud, atmospheric particulate matter |

| Liquid | Foam Example: whipped cream, shaving cream, Gas vesicles |

Emulsion or Liquid crystal Examples: milk, mayonnaise, hand cream, latex, biological membranes, micelles, lipoproteins, silk, liquid biomolecular condensates |

Sol or suspension Examples: pigmented ink, sediment, precipitates, aggregates, fibres/fibrils/filaments, crystals, solid biomolecular condensates | |

| Solid | Solid foam Examples: aerogel, styrofoam, pumice |

Gel Examples: agar, gelatin, jelly, gel-like biomolecular condensates |

Solid sol Example: cranberry glass | |

In biology, the most relevant forms of phase separation are either liquid–liquid or liquid–solid, although there have been reports of gas vesicles surrounded by a phase separated protein coat in the cytoplasm of some microorganisms.[76]

Wnt signalling

One of the first discovered examples of a highly dynamic intracellular liquid biomolecular condensate with a clear physiological function were the supramolecular complexes (Wnt signalosomes) formed by components of the Wnt signaling pathway.[44][61][62] The Dishevelled (Dsh or Dvl) protein undergoes clustering in the cytoplasm via its DIX domain, which mediates protein clustering (polymerisation) and phase separation, and is important for signal transduction.[29][30][31][32][34][44] The Dsh protein functions both in planar polarity and Wnt signalling, where it recruits another supramolecular complex (the Axin complex) to Wnt receptors at the plasma membrane. The formation of these Dishevelled and Axin containing droplets is conserved across metazoans, including in Drosophila, Xenopus, and human cells.

P granules

Another example of liquid droplets in cells are the germline P granules in Caenorhabditis elegans.[68][47] These granules separate out from the cytoplasm and form droplets, as oil does from water. Both the granules and the surrounding cytoplasm are liquid in the sense that they flow in response to forces, and two of the granules can coalesce when they come in contact. When (some of) the molecules in the granules are studied (via fluorescence recovery after photobleaching), they are found to rapidly turnover in the droplets, meaning that molecules diffuse into and out of the granules, just as expected in a liquid droplet. The droplets can also grow to be many molecules across (micrometres)[47] Studies of droplets of the Caenorhabditis elegans protein LAF-1 in vitro[77] also show liquid-like behaviour, with an apparent viscosity [math]\displaystyle{ \eta \sim 10 }[/math]Pa s. This is about a ten thousand times that of water at room temperature, but it is small enough to enable the LAF-1 droplets to flow like a liquid. Generally, interaction strength (affinity)[78] and valence (number of binding sites)[53] of the phase separating biomolecules influence their condensates viscosity, as well as their overall tendency to phase separate.

Liquid–liquid phase separation in human disease

Growing evidence suggests that anomalies in biomolecular condensates formation can lead to a number of human pathologies[79] such as cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.[80][81]

Synthetic biomolecular condensates

Biomolecular condensates can be synthesized for a number of purposes. Synthetic biomolecular condensates are inspired by endogenous biomolecular condensates, such as nucleoli, P bodies, and stress granules, which are essential to normal cellular organization and function.[82][83]

Synthetic condensates are an important tool in synthetic biology, and have a wide and growing range of applications. Engineered synthetic condensates allow for probing cellular organization, and enable the creation of novel functionalized biological materials, which have the potential to serve as drug delivery platforms and therapeutic agents.[84]

Design and control

Despite the dynamic nature and lack of binding specificity that govern the formation of biomolecular condensates, synthetic condensates can still be engineered to exhibit different behaviors. One popular way to conceptualize condensate interactions and aid in design is through the "sticker-spacer" framework.[85] Multivalent interaction sites, or "stickers", are separated by "spacers", which provide the conformational flexibility and physically separate individual interaction modules from one another. Proteins regions identified as ‘stickers’ usually consist of Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs) that act as "sticky" biopolymers via short patches of interacting residues patterned along their unstructured chain, which collectively promote LLPS.[86] By modifying the sticker-spacer framework, i.e. the polypeptide and RNA sequences as well as their mixture compositions, the material properties (viscous and elastic regimes) of condensates can be tuned to design novel condensates.[87]

Other tools outside of tuning the sticker-spacer framework can be used to give new functionality and to allow for high temporal and spatial control over synthetic condensates. One way to gain temporal control over the formation and dissolution of biomolecular condensates is by using optogenetic tools. Several different systems have been developed which allow for control of condensate formation and dissolution which rely on chimeric protein expression, and light or small molecule activation.[88] In one system,[89] proteins are expressed in a cell which contain light-activated oligomerization domains fused to IDRs. Upon irradiation with a specific wavelength of light, the oligomerization domains bind each other and form a ‘core’, which also brings multiple IDRs close together because they are fused to the oligomerization domains. The recruitment of multiple IDRs effectively creates a new biopolymer with increased valency. This increased valency allows for the IDRs to form multivalent interactions and trigger LLPS. When the activation light is stopped, the oligomerization domains disassemble, causing the dissolution of the condensate. A similar system[90] achieves the same temporal control of condensate formation by using light-sensitive ‘caged’ dimerizers. In this case, light-activation removes the dimerizer cage, allowing it to recruit IDRs to multivalent cores, which then triggers phase separation. Light-activation of a different wavelength results in the dimerizer being cleaved, which then releases the IDRs from the core and consequentially dissolves the condensate. This dimerizer system requires significantly reduced amounts of laser light to operate, which is advantageous because high intensity light can be toxic to cells.

Optogenetic systems can also be modified to gain spatial control over the formation of condensates. Multiple approaches have been developed to do so. In one approach,[91] which localizes condensates to specific genomic regions, core proteins are fused to proteins such as TRF1 or catalytically dead Cas9, which bind specific genomic loci. When oligomerization is trigger by light activation, phase separation is preferentially induced on the specific genomic region which is recognized by fusion protein. Because condensates of the same composition can interact and fuse with each other, if they are tethered to specific regions of the genome, condensates can be used to alter the spatial organization of the genome, which can have effects on gene expression.[91]

As biochemical reactors

Synthetic condensates offer a way to probe cellular function and organization with high spatial and temporal control, but can also be used to modify or add functionality to the cell. One way this is accomplished is by modifying the condensate networks to include binding sites for other proteins of interest, thus allowing the condensate to serve as a scaffold for protein release or recruitment.[92] These binding sites can be modified to be sensitive to light activation or small molecule addition, thus giving temporal control over the recruitment of a specific protein of interest. By recruiting specific proteins to condensates, reactants can be concentrated to increase reaction rates or sequestered to inhibit reactivity.[93] In addition to protein recruitment, condensates can also be designed which release proteins in response to certain stimuli. In this case, a protein of interest can be fused to a scaffold protein via a photocleavable linker. Upon irradiation, the linker is broken, and the protein is released from the condensate. Using these design principles, proteins can either be released to, or sequestered from, their native environment, allowing condensates to serve as a tool to alter the biochemical activity of specific proteins with a high level of control.[92]

Methods to study condensates

A number of experimental and computational methods have been developed to examine the physico-chemical properties and underlying molecular interactions of biomolecular condensates. Experimental approaches include phase separation assays using bright-field imaging or fluorescence microscopy, as well as fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP).[94] Computational approaches include coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations and circuit topology analysis.[95]

Coarse-grained molecular models

Molecular dynamics and Monte Carlo simulations have been extensively used to gain insights into the formation and the material properties of biomolecular condensates.[96] Although molecular models of different resolution have been employed,[97][98][99] modelling efforts have mainly focused on coarse-grained models of intrinsically disordered proteins, wherein amino acid residues are represented by single interaction sites. Compared to more detailed molecular descriptions, residue-level models provide high computational efficiency, which enables simulations to cover the long length and time scales required to study phase separation. Moreover, the resolution of these models is sufficiently detailed to capture the dependence on amino acid sequence of the properties of the system.[96]

Several residue-level models of intrinsically disordered proteins have been developed in recent years. Their common features are (i) the absence of an explicit representation of solvent molecules and salt ions, (ii) a mean-field description of the electrostatic interactions between charged residues (see Debye–Hückel theory), and (iii) a set of "stickiness" parameters which quantify the strength of the attraction between pairs of amino acids. In the development of most residue-level models, the stickiness parameters have been derived from hydrophobicity scales[100] or from a bioinformatic analysis of crystal structures of folded proteins.[101][102] Further refinement of the parameters has been achieved through iterative procedures which maximize the agreement between model predictions and a set of experiments,[103][104][105][106][107][108] or by leveraging data obtained from all-atom molecular dynamics simulations.[102]

Residue-level models of intrinsically disordered proteins have been validated by direct comparison with experimental data, and their predictions have been shown to be accurate across diverse amino acid sequences.[103][104][105][102][107][109][108] Examples of experimental data used to validate the models are radii of gyration of isolated chains and saturation concentrations, which are threshold protein concentrations above which phase separation is observed.[110]

Although intrinsically disordered proteins often play important roles in condensate formation,[111] many biomolecular condensates contain multi-domain proteins constituted by folded domains connected by intrinsically disordered regions.[112] Current residue-level models are only applicable to the study of condensates of intrinsically disordered proteins and nucleic acids.[113][102][114][115][116][108] Including an accurate description of the folded domains in these models will considerably widen their applicability.[117][96]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Garaizar, Adiran; Espinosa, Jorge R.; Joseph, Jerelle A.; Collepardo-Guevara, Rosana (2022-03-15). "Kinetic interplay between droplet maturation and coalescence modulates shape of aged protein condensates" (in en). Scientific Reports 12 (1): 4390. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-08130-2. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 35293386. Bibcode: 2022NatSR..12.4390G.

- ↑ Farlow, William G. (1890). Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 26. American Academy of Arts & Sciences. pp. 376–381.

- ↑ "The Structure of Protoplasm". Science 10 (237): 33–45. July 1899. doi:10.1126/science.10.237.33. PMID 17829686. Bibcode: 1899Sci....10...33W. https://zenodo.org/record/2117300.

- ↑ "On the structure of cell protoplasm: Part I. The Structure produced in a Cell by Fixative and Post-mortem change. The Structure of Colloidal matter and the Mechanism of Setting and of Coagulation". The Journal of Physiology 24 (2): 158–210.1. May 1899. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1899.sp000755. PMID 16992486.

- ↑ "Comparative cytological studies, with especial regard to the morphology of the nucleolus". Journal of Morphology 15 (1): 265–582. 1898. doi:10.1002/jmor.1050150204. https://archive.org/details/comparativecytol00mont.

- ↑ "Colloidal solution. The globulins". The Journal of Physiology 33 (4–5): 251–337. December 1905. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1905.sp001126. PMID 16992817.

- ↑ "The tension of composite fluid surfaces and the mechanical stability of films of fluid.". Proceedings of the Royal Society A 86 (591): 610–635. 1912. doi:10.1098/rspa.1912.0053. Bibcode: 1912RSPSA..86..610H.

- ↑ "The Mechanism of Life". 1911. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/33862/33862-h/33862-h.htm.

- ↑ "The Origin of Life". http://breadtagsagas.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/AI-Oparin-The-Origin-of-Life.pdf.

- ↑ "The Origin of Life". http://www.uv.es/~orilife/textos/Haldane.pdf.

- ↑ "Coacervation (partial miscibility in colloid systems". Proc. K. Ned. Akad. Wet 1929 32: 849–856.

- ↑ "Models for casein micelle formation". Journal of Dairy Science 56 (9): 1195–206. September 1973. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(73)85335-4. PMID 4593735.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Observation of protein diffusivity in intact human and bovine lenses with application to cataract". Investigative Ophthalmology 14 (6): 449–56. June 1975. PMID 1132941.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Phase separation of a protein-water mixture in cold cataract in the young rat lens". Science 197 (4307): 1010–2. September 1977. doi:10.1126/science.887936. PMID 887936. Bibcode: 1977Sci...197.1010T.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Cytoplasmic phase separation in formation of galactosemic cataract in lenses of young rats". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 76 (9): 4414–6. September 1979. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.9.4414. PMID 16592709. Bibcode: 1979PNAS...76.4414I.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Binary liquid phase separation and critical phenomena in a protein/water solution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 84 (20): 7079–83. October 1987. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.20.7079. PMID 3478681. Bibcode: 1987PNAS...84.7079T.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Binary-liquid phase separation of lens protein solutions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 88 (13): 5660–4. July 1991. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.13.5660. PMID 2062844. Bibcode: 1991PNAS...88.5660B.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "Cataract as a protein condensation disease: the Proctor Lecture". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 38 (10): 1911–21. September 1997. PMID 9331254. http://www.iovs.org/cgi/reprint/38/10/1911.

- ↑ "The phase transformations in starch during gelatinisation: a liquid crystalline approach". Carbohydrate Research 328 (2): 165–76. September 2000. doi:10.1016/s0008-6215(00)00098-7. PMID 11028784.

- ↑ "Gelatinisation of starch: A combined SAXS/WAXS/DSC and SANS study". Carbohydrate Research 308 (1–2): 133. 1998. doi:10.1016/S0008-6215(98)00079-2.

- ↑ "The influence of amylose on starch granule structure". International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 17 (6): 315–21. December 1995. doi:10.1016/0141-8130(96)81838-1. PMID 8789332.

- ↑ "A Universal Feature in the Structure of Starch Granules from Different Botanical Sources". Starch - Stärke 45 (12): 417. 1993. doi:10.1002/star.19930451202.

- ↑ "Liquid Crystalline Polymers". Physics Today 46 (11): 87. 1993. doi:10.1063/1.2809100. Bibcode: 1993PhT....46k..87D.

- ↑ Windle, A.H.; Donald, A.D. (1992). Liquid crystalline polymers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30666-9.

- ↑ Starch: structure and functionality. Cambridge, England: Royal Society of Chemistry. 1997. ISBN 978-0-85404-742-0.

- ↑ The importance of polymer science for biological systems: University of York. Cambridge, England: Royal Society of Chemistry. March 2008. ISBN 978-0-85404-120-6.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1991". https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1991/press-release/.

- ↑ "Ultradivided matter". Nature 412 (6845): 385. July 2001. doi:10.1038/35086662. PMID 11473291. Bibcode: 2001Natur.412..385D.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "A role of Dishevelled in relocating Axin to the plasma membrane during wingless signaling". Current Biology 13 (11): 960–6. May 2003. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00370-1. PMID 12781135.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "The Wnt signalling effector Dishevelled forms dynamic protein assemblies rather than stable associations with cytoplasmic vesicles". Journal of Cell Science 118 (Pt 22): 5269–77. November 2005. doi:10.1242/jcs.02646. PMID 16263762.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "The DIX domain of Dishevelled confers Wnt signaling by dynamic polymerization". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 14 (6): 484–92. June 2007. doi:10.1038/nsmb1247. PMID 17529994.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "Dynamic recruitment of axin by Dishevelled protein assemblies". Journal of Cell Science 120 (Pt 14): 2402–12. July 2007. doi:10.1242/jcs.002956. PMID 17606995.

- ↑ "Wnt induces LRP6 signalosomes and promotes dishevelled-dependent LRP6 phosphorylation". Science 316 (5831): 1619–22. June 2007. doi:10.1126/science.1137065. PMID 17569865. Bibcode: 2007Sci...316.1619B.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Signalosome assembly by domains undergoing dynamic head-to-tail polymerization". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 39 (10): 487–95. October 2014. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2014.08.006. PMID 25239056.

- ↑ "Stress granules: sites of mRNA triage that regulate mRNA stability and translatability". Biochemical Society Transactions 30 (Pt 6): 963–9. November 2002. doi:10.1042/bst0300963. PMID 12440955.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "Reversible compartmentalization of de novo purine biosynthetic complexes in living cells". Science 320 (5872): 103–6. April 2008. doi:10.1126/science.1152241. PMID 18388293. Bibcode: 2008Sci...320..103A.

- ↑ "Phase separation in cytoplasm, due to macromolecular crowding, is the basis for microcompartmentation". FEBS Letters 361 (2–3): 135–9. March 1995. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(95)00159-7. PMID 7698310.

- ↑ Microcompartmentation and Phase Separation in Cytoplasm. 192 (1 ed.). Academic Press. October 1999.

- ↑ "Can Cytoplasm Exist without Undergoing Phase Separation?". Microcompartmentation and Phase Separation in Cytoplasm. International Review of Cytology. 192. 1999. pp. 321–330. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(08)60532-X. ISBN 9780123645968.

- ↑ Walter, Harry (1999). "Consequences of Phase Separation in Cytoplasm". Microcompartmentation and Phase Separation in Cytoplasm. International Review of Cytology. 192. pp. 331–343. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(08)60533-1. ISBN 9780123645968.

- ↑ Sear, Richard P. (1999). "Phase behavior of a simple model of globular proteins". The Journal of Chemical Physics 111 (10): 4800–4806. doi:10.1063/1.479243. ISSN 0021-9606. Bibcode: 1999JChPh.111.4800S.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "Equilibrium cluster formation in concentrated protein solutions and colloids". Nature 432 (7016): 492–5. November 2004. doi:10.1038/nature03109. PMID 15565151. Bibcode: 2004Natur.432..492S. http://doc.rero.ch/record/4280/files/1_schurt_ecf.pdf.

- ↑ "Can visco-elastic phase separation, macromolecular crowding and colloidal physics explain nuclear organisation?". Theoretical Biology & Medical Modelling 4 (15): 15. April 2007. doi:10.1186/1742-4682-4-15. PMID 17430588.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 "Dishevelled: a protein that functions in living cells by phase separating". Soft Matter 3 (6): 680–684. May 2007. doi:10.1039/b618126k. PMID 32900127. Bibcode: 2007SMat....3..680S.

- ↑ "Phase separation of equilibrium polymers of proteins in living cells". Faraday Discussions 139: 21–34; discussion 105–28, 419–20. 2008. doi:10.1039/b713076g. PMID 19048988. Bibcode: 2008FaDi..139...21S.

- ↑ "Protein phase behavior in aqueous solutions: crystallization, liquid–liquid phase separation, gels, and aggregates". Biophysical Journal 94 (2): 570–83. January 2008. doi:10.1529/biophysj.107.116152. PMID 18160663. Bibcode: 2008BpJ....94..570D.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 "Germline P granules are liquid droplets that localize by controlled dissolution/condensation". Science 324 (5935): 1729–32. June 2009. doi:10.1126/science.1172046. PMID 19460965. Bibcode: 2009Sci...324.1729B.

- ↑ "Liquid droplet formation by HP1α suggests a role for phase separation in heterochromatin". Nature 547 (7662): 236–240. July 2017. doi:10.1038/nature22822. PMID 28636604. Bibcode: 2017Natur.547..236L.

- ↑ "Phase transition of a disordered nuage protein generates environmentally responsive membraneless organelles". Molecular Cell 57 (5): 936–947. March 2015. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.013. PMID 25747659.

- ↑ "A Liquid-to-Solid Phase Transition of the ALS Protein FUS Accelerated by Disease Mutation". Cell 162 (5): 1066–77. August 2015. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.047. PMID 26317470.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 "Coexisting Liquid Phases Underlie Nucleolar Subcompartments". Cell 165 (7): 1686–1697. June 2016. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.047. PMID 27212236.

- ↑ "Composition dependent phase separation underlies directional flux through the nucleolus" (in en). bioRxiv: 809210. 2019-10-22. doi:10.1101/809210.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 "Phase transitions in the assembly of multivalent signalling proteins". Nature 483 (7389): 336–40. March 2012. doi:10.1038/nature10879. PMID 22398450. Bibcode: 2012Natur.483..336L.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 "Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 18 (5): 285–298. May 2017. doi:10.1038/nrm.2017.7. PMID 28225081.

- ↑ "Controlling compartmentalization by non-membrane-bound organelles". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 373 (1747): 4666–4684. May 2018. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0193. PMID 29632271.

- ↑ "Expansion of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Increases the Range of Stability of Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation". Molecules 25 (20): 4705. October 2020. doi:10.3390/molecules25204705. PMID 33076213.

- ↑ "Cross-β Polymerization of Low Complexity Sequence Domains". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 9 (3): a023598. March 2017. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a023598. PMID 27836835.

- ↑ "Head-to-Tail Polymerization in the Assembly of Biomolecular Condensates". Cell 182 (4): 799–811. August 2020. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.037. PMID 32822572.

- ↑ "Glycogen-Surfactant Complexes: Phase Behavior in a Water/Phytoglycogen/Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) System". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 61 (12): 2063–8. January 1997. doi:10.1271/bbb.61.2063. PMID 27396883.

- ↑ Esposito, Mark; Fang, Cao; Cook, Katelyn C.; Park, Nana; Wei, Yong; Spadazzi, Chiara; Bracha, Dan; Gunaratna, Ramesh T. et al. (March 2021). "TGF-β-induced DACT1 biomolecular condensates repress Wnt signalling to promote bone metastasis" (in en). Nature Cell Biology 23 (3): 257–267. doi:10.1038/s41556-021-00641-w. ISSN 1476-4679. PMID 33723425.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 "Wnt/Beta-Catenin Signaling Regulation and a Role for Biomolecular Condensates". Developmental Cell 48 (4): 429–444. February 2019. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2019.01.025. PMID 30782412.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 "Multiprotein complexes governing Wnt signal transduction". Current Opinion in Cell Biology 51 (1): 42–49. April 2018. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2017.10.008. PMID 29153704.

- ↑ "Phase-separated bacterial ribonucleoprotein bodies organize mRNA decay". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. RNA 11 (6): e1599. November 2020. doi:10.1002/wrna.1599. PMID 32445438.

- ↑ Dorone, Yanniv; Boeynaems, Steven; Jin, Benjamin; Bossi, Flavia; Flores, Eduardo; Lazarus, Elena; Michiels, Emiel; De Decker, Mathias et al. (July 2021). "A prion-like protein regulator of seed germination undergoes hydration-dependent phase separation.". Cell 184 (16): 4284–4298.e27. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.009. PMID 34233164. PMC 8513799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.009.

- ↑ "Regulation of Transmembrane Signaling by Phase Separation". Annual Review of Biophysics 48 (1): 465–494. May 2019. doi:10.1146/annurev-biophys-052118-115534. PMID 30951647.

- ↑ Muschol, Martin; Rosenberger, Franz (1997). "Liquid–liquid phase separation in supersaturated lysozyme solutions and associated precipitate formation/crystallization". The Journal of Chemical Physics 107 (6): 1953–1962. doi:10.1063/1.474547. ISSN 0021-9606. Bibcode: 1997JChPh.107.1953M.

- ↑ "Biophysical characterization of monofilm model systems composed of selected tear film phospholipids". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1858 (2): 403–14. February 2016. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.11.025. PMID 26657693.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 "Optogenetic tools light up phase separation". Nature Methods 16 (2): 139. February 2019. doi:10.1038/s41592-019-0310-5. PMID 30700901.(Subscription content?)

- ↑ "Liquid–liquid phase separation in biology". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 30 (1): 39–58. 2014-10-11. doi:10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013325. PMID 25288112.

- ↑ "Evaluating phase separation in live cells: diagnosis, caveats, and functional consequences". Genes & Development 33 (23–24): 1619–1634. December 2019. doi:10.1101/gad.331520.119. PMID 31594803.

- ↑ "Phase Separation of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins". Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Methods in Enzymology. 611. Elsevier. 2018. pp. 1–30. doi:10.1016/bs.mie.2018.09.035. ISBN 978-0-12-815649-0.

- ↑ "Organization and Function of Non-dynamic Biomolecular Condensates". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 43 (2): 81–94. February 2018. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2017.11.005. PMID 29258725.

- ↑ "Protein Phase Separation: A New Phase in Cell Biology". Trends in Cell Biology 28 (6): 420–435. June 2018. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2018.02.004. PMID 29602697.

- ↑ de Swaan Arons, J.; Diepen, G. A. M. (2010). "Immiscibility of gases. The system He-Xe: (Short communication)". Recueil des Travaux Chimiques des Pays-Bas 82 (8): 806. doi:10.1002/recl.19630820810. ISSN 0165-0513.

- ↑ de Swaan Arons, J.; Diepen, G. A. M. (1966). "Gas—Gas Equilibria". J. Chem. Phys. 44 (6): 2322. doi:10.1063/1.1727043. Bibcode: 1966JChPh..44.2322D.

- ↑ "An amyloid organelle, solid-state NMR evidence for cross-β assembly of gas vesicles". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 287 (5): 3479–84. January 2012. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.313049. PMID 22147705.

- ↑ "The disordered P granule protein LAF-1 drives phase separation into droplets with tunable viscosity and dynamics". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (23): 7189–94. June 2015. doi:10.1073/pnas.1504822112. PMID 26015579. Bibcode: 2015PNAS..112.7189E.

- ↑ "Designer protein assemblies with tunable phase diagrams in living cells". Nature Chemical Biology 16 (9): 939–945. September 2020. doi:10.1038/s41589-020-0576-z. PMID 32661377.

- ↑ "Phase Separation: Linking Cellular Compartmentalization to Disease". Trends in Cell Biology 26 (7): 547–558. July 2016. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2016.03.004. PMID 27051975.

- ↑ "Liquid phase condensation in cell physiology and disease". Science 357 (6357): eaaf4382. September 2017. doi:10.1126/science.aaf4382. PMID 28935776.

- ↑ "Are aberrant phase transitions a driver of cellular aging?". BioEssays 38 (10): 959–68. October 2016. doi:10.1002/bies.201600042. PMID 27554449.

- ↑ P. Ivanov, N. Kedersha, and P. Anderson, “Stress granules and processing bodies in translational control,” Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, vol. 11, no. 5, 2019.

- ↑ C. P. Brangwynne, T. J. Mitchison, and A. A. Hyman, “Active liquid-like behavior of nucleoli determines their size and shape in Xenopus laevis oocytes,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 108, no. 11, pp. 4334–4339, 2011.

- ↑ D. Bracha, M. T. Walls, and C. P. Brangwynne, “Probing and engineering liquid-phase organelles,” Nature Biotechnology, vol. 37, no. 12, pp. 1435–1445, 2019.

- ↑ Choi, J.M.; Dar, F.; Pappu, R.V. (2019). "LASSI: A lattice model for simulating phase transitions of multivalent proteins". PLOS Computational Biology 15 (10): e1007028. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007028. PMID 31634364. Bibcode: 2019PLSCB..15E7028C.

- ↑ Hastings, R.L.; Boeynaems, S. (June 2021). "Designer Condensates: A Toolkit for the Biomolecular Architect". Journal of Molecular Biology 433 (12): 166837. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2021.166837. PMID 33539874.

- ↑ Tejedor, R.; Garaizar, A.; Ramı, J. (December 2021). "RNA modulation of transport properties and stability in phase-separated condensates". Biophysical Journal 120 (23): 5169–5186. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2021.11.003. PMID 34762868. Bibcode: 2021BpJ...120.5169T.

- ↑ C. D. Reinkemeier and E. A. Lemke, “Synthetic biomolecular condensates to engineer eukaryotic cells,” Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, vol. 64, pp. 174–181, 2021.

- ↑ D. Bracha, M. T. Walls, M. T. Wei, L. Zhu, M. Kurian, J. L. Avalos, J. E. Toettcher, and C. P. Brangwynne, “Mapping Local and Global Liquid Phase Behavior in Living Cells Using Photo-Oligomerizable Seeds,” Cell, vol. 175, no. 6, pp. 1467–1480.e13, 2018.

- ↑ H. Zhang, C. Aonbangkhen, E. V. Tarasovetc, E. R. Ballister, D. M.Chenoweth, and M. A. Lampson, “Optogenetic control of kinetochore function,” Nature Chemical Biology, vol. 13, pp. 1096–1101, Aug 2017.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Y. Shin, Y. C. Chang, D. S. Lee, J. Berry, D. W. Sanders, P. Ronceray, N. S.Wingreen, M. Haataja, and C. P. Brangwynne, “Liquid Nuclear Condensates Mechanically Sense and Restructure the Genome,” Cell, vol. 175, no. 6,pp. 1481–1491.e13, 2018.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 M. Yoshikawa and S. Tsukiji, “Modularly Built Synthetic Membraneless Organelles Enabling Targeted Protein Sequestration and Release,” Biochemistry, Oct 2021.

- ↑ Y. Shin and C. P. Brangwynne, “Liquid phase condensation in cell physiology and disease,” Science, vol. 357, Sep 2017.

- ↑ Methods to Study Phase-Separated Condensates and the Underlying Molecular Interactions

- ↑ Maziar Heidari et al., A topology framework for macromolecular complexes and condensates. Nano Research (2022)

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 96.2 Saar, Kadi L.; Qian, Daoyuan; Good, Lydia L.; Morgunov, Alexey S.; Collepardo-Guevara, Rosana; Best, Robert B.; Knowles, Tuomas P. J. (12 May 2023). "Theoretical and Data-Driven Approaches for Biomolecular Condensates". Chemical Reviews 123 (14): 8988–9009. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00586. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 37171907.

- ↑ Paloni, Matteo; Bailly, Rémy; Ciandrini, Luca; Barducci, Alessandro (16 September 2020). "Unraveling Molecular Interactions in Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation of Disordered Proteins by Atomistic Simulations". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 124 (41): 9009–9016. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c06288. ISSN 1520-6106. PMID 32936641.

- ↑ Benayad, Zakarya; von Bülow, Sören; Stelzl, Lukas S.; Hummer, Gerhard (14 December 2020). "Simulation of FUS Protein Condensates with an Adapted Coarse-Grained Model". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 17 (1): 525–537. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.0c01064. ISSN 1549-9618. PMID 33307683.

- ↑ Espinosa, Jorge R.; Joseph, Jerelle A.; Sanchez-Burgos, Ignacio; Garaizar, Adiran; Frenkel, Daan; Collepardo-Guevara, Rosana (June 2020). "Liquid network connectivity regulates the stability and composition of biomolecular condensates with many components". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (24): 13238–13247. doi:10.1073/pnas.1917569117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 32482873. Bibcode: 2020PNAS..11713238E.

- ↑ Dignon, Gregory L.; Zheng, Wenwei; Kim, Young C.; Best, Robert B.; Mittal, Jeetain (24 January 2018). "Sequence determinants of protein phase behavior from a coarse-grained model". PLOS Computational Biology 14 (1): e1005941. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005941. PMID 29364893. Bibcode: 2018PLSCB..14E5941D.

- ↑ Vernon, Robert McCoy; Chong, Paul Andrew; Tsang, Brian; Kim, Tae Hun; Bah, Alaji; Farber, Patrick; Lin, Hong; Forman-Kay, Julie Deborah (9 February 2018). "Pi-Pi contacts are an overlooked protein feature relevant to phase separation". eLife 7. doi:10.7554/eLife.31486. PMID 29424691.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 102.2 102.3 Joseph, Jerelle A.; Reinhardt, Aleks; Aguirre, Anne; Chew, Pin Yu; Russell, Kieran O.; Espinosa, Jorge R.; Garaizar, Adiran; Collepardo-Guevara, Rosana (22 November 2021). "Physics-driven coarse-grained model for biomolecular phase separation with near-quantitative accuracy". Nature Computational Science 1 (11): 732–743. doi:10.1038/s43588-021-00155-3. PMID 35795820.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Regy, Roshan Mammen; Thompson, Jacob; Kim, Young C.; Mittal, Jeetain (24 May 2021). "Improved coarse‐grained model for studying sequence dependent phase separation of disordered proteins". Protein Science 30 (7): 1371–1379. doi:10.1002/pro.4094. ISSN 0961-8368. PMID 33934416.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 Dannenhoffer-Lafage, Thomas; Best, Robert B. (20 April 2021). "A Data-Driven Hydrophobicity Scale for Predicting Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation of Proteins". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 125 (16): 4046–4056. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c11479. ISSN 1520-6106. PMID 33876938.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Latham, Andrew P.; Zhang, Bin (7 April 2021). "Consistent Force Field Captures Homologue-Resolved HP1 Phase Separation". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 17 (5): 3134–3144. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.0c01220. ISSN 1549-9618. PMID 33826337.

- ↑ Tesei, Giulio; Schulze, Thea K.; Crehuet, Ramon; Lindorff-Larsen, Kresten (29 October 2021). "Accurate model of liquid–liquid phase behavior of intrinsically disordered proteins from optimization of single-chain properties". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (44). doi:10.1073/pnas.2111696118. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 34716273. Bibcode: 2021PNAS..11811696T.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 Farag, Mina; Cohen, Samuel R.; Borcherds, Wade M.; Bremer, Anne; Mittag, Tanja; Pappu, Rohit V. (13 December 2022). "Condensates formed by prion-like low-complexity domains have small-world network structures and interfaces defined by expanded conformations". Nature Communications 13 (1): 7722. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-35370-7. PMID 36513655. Bibcode: 2022NatCo..13.7722F.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 108.2 Valdes-Garcia, Gilberto; Heo, Lim; Lapidus, Lisa J.; Feig, Michael (6 January 2023). "Modeling Concentration-dependent Phase Separation Processes Involving Peptides and RNA via Residue-Based Coarse-Graining". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 19 (2): 669–678. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.2c00856. ISSN 1549-9618. PMID 36607820.

- ↑ Tesei, Giulio; Lindorff-Larsen, Kresten (17 January 2023). "Improved predictions of phase behaviour of intrinsically disordered proteins by tuning the interaction range". Open Research Europe 2: 94. doi:10.12688/openreseurope.14967.2. PMID 37645312.

- ↑ Mittag, Tanja; Pappu, Rohit V. (June 2022). "A conceptual framework for understanding phase separation and addressing open questions and challenges". Molecular Cell 82 (12): 2201–2214. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2022.05.018. ISSN 1097-2765. PMID 35675815. PMC 9233049. https://pubag.nal.usda.gov/catalog/7806056.

- ↑ Borcherds, Wade; Bremer, Anne; Borgia, Madeleine B; Mittag, Tanja (April 2021). "How do intrinsically disordered protein regions encode a driving force for liquid–liquid phase separation?". Current Opinion in Structural Biology 67: 41–50. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2020.09.004. ISSN 0959-440X. PMID 33069007.

- ↑ Ghosh, Soumyadeep (April 28, 2023). "Scaffolds and Clients". https://wiki.cd-code.org/functional-type.

- ↑ Regy, Roshan Mammen; Dignon, Gregory L; Zheng, Wenwei; Kim, Young C; Mittal, Jeetain (2 December 2020). "Sequence dependent phase separation of protein-polynucleotide mixtures elucidated using molecular simulations". Nucleic Acids Research 48 (22): 12593–12603. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa1099. ISSN 0305-1048. PMID 33264400.

- ↑ Lebold, Kathryn M.; Best, Robert B. (23 March 2022). "Tuning Formation of Protein–DNA Coacervates by Sequence and Environment". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 126 (12): 2407–2419. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.2c00424. ISSN 1520-6106. PMID 35317553.

- ↑ Leicher, Rachel; Osunsade, Adewola; Chua, Gabriella N. L.; Faulkner, Sarah C.; Latham, Andrew P.; Watters, John W.; Nguyen, Tuan; Beckwitt, Emily C. et al. (28 April 2022). "Single-stranded nucleic acid binding and coacervation by linker histone H1". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 29 (5): 463–471. doi:10.1038/s41594-022-00760-4. ISSN 1545-9993. PMID 35484234.

- ↑ Farr, Stephen E.; Woods, Esmae J.; Joseph, Jerelle A.; Garaizar, Adiran; Collepardo-Guevara, Rosana (17 May 2021). "Nucleosome plasticity is a critical element of chromatin liquid–liquid phase separation and multivalent nucleosome interactions". Nature Communications 12 (1): 2883. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-23090-3. PMID 34001913. Bibcode: 2021NatCo..12.2883F.

- ↑ Latham, Andrew P.; Zhang, Bin (February 2022). "Unifying coarse-grained force fields for folded and disordered proteins". Current Opinion in Structural Biology 72: 63–70. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2021.08.006. ISSN 0959-440X. PMID 34536913.

Further reading

- "Who's In and Who's Out-Compositional Control of Biomolecular Condensates". Journal of Molecular Biology 430 (23): 4666–4684. November 2018. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2018.08.003. PMID 30099028.

- "Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 18 (5): 285–298. May 2017. doi:10.1038/nrm.2017.7. PMID 28225081.

- "Liquid–liquid phase separation in biology". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 30: 39–58. 2014. doi:10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013325. PMID 25288112.

- "What lava lamps and vinaigrette can teach us about cell biology". Nature 555 (7696): 300–302. March 2018. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-03070-2. PMID 29542707. Bibcode: 2018Natur.555..300D.

|