Biology:Methanotroph

Methanotrophs (sometimes called methanophiles) are prokaryotes that metabolize methane as their source of carbon and to unlock the energy of oxygen,[1] nitrate, sulfate, or other oxidized species. They are bacteria or archaea, can grow aerobically or anaerobically, and require single-carbon compounds to survive.

Methanotrophs are especially common in or near environments where methane is produced, although some methanotrophs can oxidize atmospheric methane. Their habitats include wetlands, soils, marshes, rice paddies, landfills, aquatic systems (lakes, oceans, streams) and more. They are of special interest to researchers studying global warming, as they play a significant role in the global methane budget, by reducing the amount of methane emitted to the atmosphere.[2][3]

Methanotrophy is a special case of methylotrophy, using single-carbon compounds that are more reduced than carbon dioxide. Some methylotrophs, however, can also make use of multi-carbon compounds; this differentiates them from methanotrophs, which are usually fastidious methane and methanol oxidizers. The only facultative methanotrophs isolated to date are members of the genus Methylocella silvestris,[4][5] Methylocapsa aurea[6] and several Methylocystis strains.[7]

In functional terms, methanotrophs are referred to as methane-oxidizing bacteria. However, methane-oxidizing bacteria encompass other organisms that are not regarded as sole methanotrophs. For this reason, methane-oxidizing bacteria have been separated into subgroups: methane-assimilating bacteria (MAB) groups, the methanotrophs, and autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AAOB), which cooxidize methane.[3]

Classification

Methantrophs can be either bacteria or archaea. Which methanotroph species is present is mainly determined by the availability of electron acceptors. Many types of methane oxidizing bacteria (MOB) are known. Differences in the method of formaldehyde fixation and membrane structure divide these bacterial methanotrophs into several groups. There are several subgroups among the methanotrophic archaea.

Aerobic

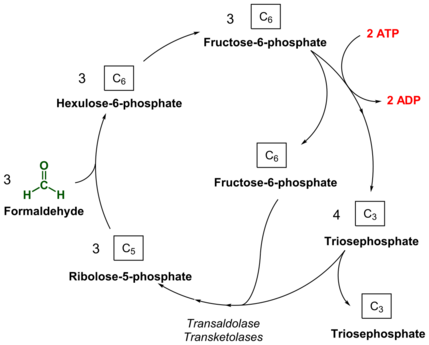

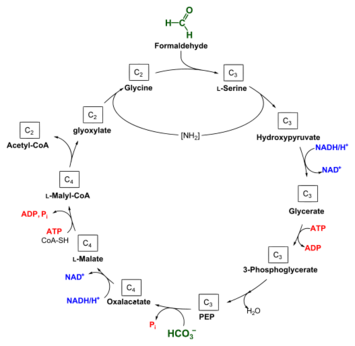

Under aerobic conditions, methanotrophs combine oxygen and methane to form formaldehyde, which is then incorporated into organic compounds via the serine pathway or the ribulose monophosphate (RuMP) pathway, and carbon dioxide, which is released. Type I and type X methanotrophs are part of the Gammaproteobacteria and they use the RuMP pathway to assimilate carbon. Type II methanotrophs are part of the Alphaproteobacteria and use the serine pathway of carbon assimilation. They also characteristically have a system of internal membranes within which methane oxidation occurs. Methanotrophs in Gammaproteobacteria are known from the family Methylococcaceae.[8] Methanotrophs from Alphaproteobacteria are found in families Methylocystaceae and Beijerinckiaceae.

Aerobic methanotrophs are also known from the Methylacidiphilaceae (phylum Verrucomicrobia).[9] In contrast to Gammaproteobacteria and Alphaproteobacteria, methanotrophs in the phylum Verrucomicrobia are mixotrophs.[10][11] In 2021 a bacterial bin from the phylum Gemmatimonadetes called Candidatus Methylotropicum kingii showing aerobic methanotrophy was discovered thus suggesting methanotrophy to be present in the four bacterial phyla.[12]

In some cases, aerobic methane oxidation can take place in anoxic environments. Candidatus Methylomirabilis oxyfera belongs to the phylum NC10 bacteria, and can catalyze nitrite reduction through an "intra-aerobic" pathway, in which internally produced oxygen is used to oxidise methane.[13][14] In clear water lakes, methanotrophs can live in the anoxic water column, but receive oxygen from photosynthetic organisms, which they then directly consume to oxidize methane.[15]

No aerobic methanotrophic archaea are known.

Anaerobic

Under anoxic conditions, methanotrophs use different electron acceptors for methane oxidation. This can happen in anoxic habitats such as marine or lake sediments, oxygen minimum zones, anoxic water columns, rice paddies and soils. Some specific methanotrophs can reduce nitrate,[16] nitrite,[17] iron,[18] sulfate,[19] or manganese ions and couple that to methane oxidation without syntrophic partner. Investigations in marine environments revealed that methane can be oxidized anaerobically by consortia of methane oxidizing archaea and sulfate-reducing bacteria.[20][21] This type of anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) mainly occurs in anoxic marine sediments. The exact mechanism is still a topic of debate but the most widely accepted theory is that the archaea use the reversed methanogenesis pathway to produce carbon dioxide and another, unknown intermediate, which is then used by the sulfate-reducing bacteria to gain energy from the reduction of sulfate to hydrogen sulfide and water.

The anaerobic methanotrophs are not related to the known aerobic methanotrophs; the closest cultured relatives to the anaerobic methanotrophs are the methanogens in the order Methanosarcinales.[22]

Special species

Methylococcus capsulatus is used to produce animal feed from natural gas.[23]

In 2010 a new bacterium Candidatus Methylomirabilis oxyfera from the phylum NC10 was identified that can couple the anaerobic oxidation of methane to nitrite reduction without the need for a syntrophic partner.[13] Based on studies of Ettwig et al.,[13] it is believed that M. oxyfera oxidizes methane anaerobically by utilizing oxygen produced internally from the dismutation of nitric oxide into nitrogen and oxygen gas.

Taxonomy

Many methanotrophic cultures have been isolated and formally characterized over the past 5 decades, starting with the classical study of Whittenbury (Whittenbury et al., 1970). Currently, 18 genera of cultivated aerobic methanotrophic Gammaproteobacteria and 5 genera of Alphaproteobacteria are known, represented by approx. 60 different species.[24]

Methane oxidation

Methanotrophs oxidize methane by first initiating reduction of an oxygen atom to H2O2 and transformation of methane to CH3OH using methane monooxygenases (MMOs).[25] Furthermore, two types of MMO have been isolated from methanotrophs: soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO) and particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO).

Cells containing pMMO have demonstrated higher growth capabilities and higher affinity for methane than sMMO containing cells.[25] It is suspected that copper ions may play a key role in both pMMO regulation and the enzyme catalysis, thus limiting pMMO cells to more copper-rich environments than sMMO producing cells.[26]

See also

References

- ↑ Schmidt-Rohr, K. (2020). "Oxygen Is the High-Energy Molecule Powering Complex Multicellular Life: Fundamental Corrections to Traditional Bioenergetics". ACS Omega 5: 2221-2233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b03352

- ↑ "Importance of methane-oxidizing bacteria in the methane budget as revealed by the use of a specific inhibitor". Nature 356 (6368): 421–423. 1992. doi:10.1038/356421a0. Bibcode: 1992Natur.356..421O.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Characterization of methanotrophic bacterial populations in soils showing atmospheric methane uptake". Applied and Environmental Microbiology 65 (8): 3312–8. August 1999. doi:10.1128/AEM.65.8.3312-3318.1999. PMID 10427012. Bibcode: 1999ApEnM..65.3312H.

- ↑ "Methylocella species are facultatively methanotrophic". Journal of Bacteriology 187 (13): 4665–70. July 2005. doi:10.1128/JB.187.13.4665-4670.2005. PMID 15968078.

- ↑ "Complete genome sequence of the aerobic facultative methanotroph Methylocella silvestris BL2". Journal of Bacteriology 192 (14): 3840–1. July 2010. doi:10.1128/JB.00506-10. PMID 20472789.

- ↑ "Methylocapsa aurea sp. nov., a facultative methanotroph possessing a particulate methane monooxygenase, and emended description of the genus Methylocapsa". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 60 (Pt 11): 2659–2664. November 2010. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.020149-0. PMID 20061505.

- ↑ "Acetate utilization as a survival strategy of peat-inhabiting Methylocystis spp". Environmental Microbiology Reports 3 (1): 36–46. February 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00180.x. PMID 23761229. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00180.x.

- ↑ "Aerobic Methanotrophy and Nitrification: Processes and Connections" (in en). eLS. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2012-04-16. pp. a0022213. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0022213. ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/9780470015902.a0022213. Retrieved 2021-01-17.

- ↑ "Environmental, genomic and taxonomic perspectives on methanotrophic Verrucomicrobia". Environmental Microbiology Reports 1 (5): 293–306. October 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00022.x. PMID 23765882. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00022.x.

- ↑ "Mixotrophy drives niche expansion of verrucomicrobial methanotrophs". The ISME Journal 11 (11): 2599–2610. November 2017. doi:10.1038/ismej.2017.112. PMID 28777381.

- ↑ "Detection of autotrophic verrucomicrobial methanotrophs in a geothermal environment using stable isotope probing". Frontiers in Microbiology 3: 303. 2012. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00303. PMID 22912630.

- ↑ "Trace gas oxidizers are widespread and active members of soil microbial communities". Nature Microbiology 6 (2): 246–256. January 2021. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-00811-w. PMID 33398096. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41564-020-00811-w.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Nitrite-driven anaerobic methane oxidation by oxygenic bacteria". Nature 464 (7288): 543–8. March 2010. doi:10.1038/nature08883. PMID 20336137. Bibcode: 2010Natur.464..543E. https://hal-cea.archives-ouvertes.fr/cea-00907649/file/Ett.pdf.

- ↑ "Anaerobic oxidization of methane in a minerotrophic peatland: enrichment of nitrite-dependent methane-oxidizing bacteria". Applied and Environmental Microbiology 78 (24): 8657–65. December 2012. doi:10.1128/AEM.02102-12. PMID 23042166. Bibcode: 2012ApEnM..78.8657Z.

- ↑ "Methane oxidation coupled to oxygenic photosynthesis in anoxic waters". The ISME Journal 9 (9): 1991–2002. September 2015. doi:10.1038/ismej.2015.12. PMID 25679533.

- ↑ "Anaerobic oxidation of methane coupled to nitrate reduction in a novel archaeal lineage". Nature 500 (7464): 567–70. August 2013. doi:10.1038/nature12375. PMID 23892779. Bibcode: 2013Natur.500..567H.

- ↑ "Nitrite-driven anaerobic methane oxidation by oxygenic bacteria". Nature 464 (7288): 543–8. March 2010. doi:10.1038/nature08883. PMID 20336137. Bibcode: 2010Natur.464..543E. http://www.nature.com/articles/nature08883.

- ↑ "Archaea catalyze iron-dependent anaerobic oxidation of methane". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113 (45): 12792–12796. November 2016. doi:10.1073/pnas.1609534113. PMID 27791118.

- ↑ "Zero-valent sulphur is a key intermediate in marine methane oxidation". Nature 491 (7425): 541–6. November 2012. doi:10.1038/nature11656. PMID 23135396. Bibcode: 2012Natur.491..541M. http://www.nature.com/articles/nature11656.

- ↑ "Archaea in biogeochemical cycles". Annual Review of Microbiology 67 (1): 437–57. 2013-09-08. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155614. PMID 23808334.

- ↑ "Anaerobic oxidation of methane with sulfate: on the reversibility of the reactions that are catalyzed by enzymes also involved in methanogenesis from CO2". Current Opinion in Microbiology 14 (3): 292–9. June 2011. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2011.03.003. PMID 21489863.

- ↑ "A marine microbial consortium apparently mediating anaerobic oxidation of methane". Nature 407 (6804): 623–6. October 2000. doi:10.1038/35036572. PMID 11034209. Bibcode: 2000Natur.407..623B. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/12290603.

- ↑ "Food made from natural gas will soon feed farm animals – and us" (in en-US). New Scientist. 2016-11-19. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2112298-food-made-from-natural-gas-will-soon-feed-farm-animals-and-us/.

- ↑ "Phylogenomic Analysis of the Gammaproteobacterial Methanotrophs (Order Methylococcales) Calls for the Reclassification of Members at the Genus and Species Levels". Frontiers in Microbiology 9: 3162. 2018. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.03162. PMID 30631317.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Methanotrophic bacteria". Microbiological Reviews 60 (2): 439–71. June 1996. doi:10.1128/MMBR.60.2.439-471.1996. PMID 8801441.

- ↑ "Biological methane oxidation: regulation, biochemistry, and active site structure of particulate methane monooxygenase". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 39 (3): 147–64. 2004. doi:10.1080/10409230490475507. PMID 15596549.

External links

- Anaerobic oxidation of methane

- Methane-Eating Bug Holds Promise For Cutting Greenhouse Gas. Media Release, GNS Science, New Zealand