One-key MAC

One-key MAC (OMAC) is a family of message authentication codes constructed from a block cipher much like the CBC-MAC algorithm. It may be used to provide assurance of the authenticity and, hence, the integrity of data. Two versions are defined:

- The original OMAC of February 2003, which is rarely used.[1] The preferred name is now "OMAC2".[2]

- The OMAC1 refinement,[2] which became an NIST recommendation in May 2005 under the name CMAC.[3]

OMAC is free for all uses: it is not covered by any patents.[4]

History

The core of the CMAC algorithm is a variation of CBC-MAC that Black and Rogaway proposed and analyzed under the name "XCBC"[5] and submitted to NIST.[6] The XCBC algorithm efficiently addresses the security deficiencies of CBC-MAC, but requires three keys.

Iwata and Kurosawa proposed an improvement of XCBC that requires less key material (just one key) and named the resulting algorithm One-Key CBC-MAC (OMAC) in their papers.[1] They later submitted the OMAC1 (= CMAC),[2] a refinement of OMAC, and additional security analysis.[7]

Algorithm

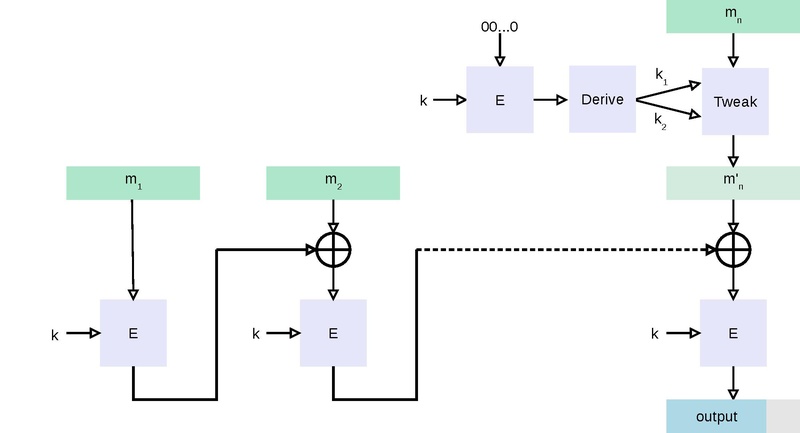

To generate an ℓ-bit CMAC tag (t) of a message (m) using a b-bit block cipher (E) and a secret key (k), one first generates two b-bit sub-keys (k1 and k2) using the following algorithm (this is equivalent to multiplication by x and x2 in a finite field GF(2b)). Let ≪ denote the standard left-shift operator and ⊕ denote bit-wise exclusive or:

- Calculate a temporary value k0 = Ek(0).

- If msb(k0) = 0, then k1 = k0 ≪ 1, else k1 = (k0 ≪ 1) ⊕ C; where C is a certain constant that depends only on b. (Specifically, C is the non-leading coefficients of the lexicographically first irreducible degree-b binary polynomial with the minimal number of ones: 0x1B for 64-bit, 0x87 for 128-bit, and 0x425 for 256-bit blocks.)

- If msb(k1) = 0, then k2 = k1 ≪ 1, else k2 = (k1 ≪ 1) ⊕ C.

- Return keys (k1, k2) for the MAC generation process.

As a small example, suppose b = 4, C = 00112, and k0 = Ek(0) = 01012. Then k1 = 10102 and k2 = 0100 ⊕ 0011 = 01112.

The CMAC tag generation process is as follows:

- Divide message into b-bit blocks m = m1 ∥ ... ∥ mn−1 ∥ mn, where m1, ..., mn−1 are complete blocks. (The empty message is treated as one incomplete block.)

- If mn is a complete block then mn′ = k1 ⊕ mn else mn′ = k2 ⊕ (mn ∥ 10...02).

- Let c0 = 00...02.

- For i = 1, ..., n − 1, calculate ci = Ek(ci−1 ⊕ mi).

- cn = Ek(cn−1 ⊕ mn′)

- Output t = msbℓ(cn).

The verification process is as follows:

- Use the above algorithm to generate the tag.

- Check that the generated tag is equal to the received tag.

Variants

CMAC-C1[8] is a variant of CMAC that provides additional commitment and context-discovery security guarantees.

Implementations

- Python implementation: see the usage of the

AES_CMAC()function in "impacket/blob/master/tests/misc/test_crypto.py", and its definition in "impacket/blob/master/impacket/crypto.py"[9] - Ruby implementation[10]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Iwata, Tetsu; Kurosawa, Kaoru (2003-02-24). "OMAC: One-Key CBC MAC" (in en). Fast Software Encryption. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2887. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 129–153. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-39887-5_11. ISBN 978-3-540-20449-7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Iwata, Tetsu; Kurosawa, Kaoru (2003). OMAC: One-Key CBC MAC – Addendum. https://csrc.nist.gov/groups/ST/toolkit/BCM/documents/proposedmodes/omac/omac-ad.pdf. "In this note, we propose OMAC1, a new choice of the parameters of OMAC-family (see [4] for the details). Test vectors are also presented. Accordingly, we rename the previous OMAC as OMAC2. (That is to say, test vectors for OMAC2 were already shown in [3].) We use OMAC as a generic name for OMAC1 and OMAC2.".

- ↑ Dworkin, Morris (2016). Recommendation for Block Cipher Modes of Operation: The CMAC Mode for Authentication. doi:10.6028/nist.sp.800-38b. https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-38b.pdf.

- ↑ Rogaway, Phillip. "CMAC: Non-licensing". https://www.cs.ucdavis.edu/~rogaway/xcbc/ip.html. "Phillip Rogaway's statement on intellectual property status of CMAC"

- ↑ Black, John; Rogaway, Phillip (2000-08-20) (in en). Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2000. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 197–215. doi:10.1007/3-540-44598-6_12. ISBN 978-3540445982.

- ↑ Black, J; Rogaway, P. A Suggestion for Handling Arbitrary-Length Messages with the CBC MAC. https://web.cs.ucdavis.edu/~rogaway/papers/xcbc.pdf.

- ↑ Iwata, Tetsu; Kurosawa, Kaoru (2003-12-08). "Stronger Security Bounds for OMAC, TMAC, and XCBC". in Johansson, Thomas (in en). Progress in Cryptology - INDOCRYPT 2003. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2904. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 402–415. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-24582-7_30. ISBN 9783540206095. https://archive.org/details/progresscryptolo00joha.

- ↑ Bhaumik, Ritam; Chakraborty, Bishwajit; Choi, Wonseok; Dutta, Avijit; Govinden, Jérôme; Shen, Yaobin (2024). "The Committing Security of MACs with Applications to Generic Composition". in Reyzin, Leonid; Stebila, Douglas (in en). Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 14923. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. pp. 425–462. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-68385-5_14. ISBN 978-3-031-68385-5. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-68385-5_14.

- ↑ "Impacket is a collection of Python classes for working with network protocols.: SecureAuthCorp/impacket". 15 December 2018. https://github.com/SecureAuthCorp/impacket.

- ↑ "Ruby C extension for the AES-CMAC keyed hash function (RFC 4493): louismullie/cmac-rb". 4 May 2016. https://github.com/louismullie/cmac-rb.

External links

- RFC 4493 The AES-CMAC Algorithm

- RFC 4494 The AES-CMAC-96 Algorithm and Its Use with IPsec

- RFC 4615 The Advanced Encryption Standard-Cipher-based Message Authentication Code-Pseudo-Random Function-128 (AES-CMAC-PRF-128)

- OMAC Online Test

- More information on OMAC

- Rust implementation

|