Component (graph theory)

In graph theory, a component of an undirected graph is a connected subgraph that is not part of any larger connected subgraph. The components of any graph partition its vertices into disjoint sets, and are the induced subgraphs of those sets. A graph that is itself connected has exactly one component, consisting of the whole graph. Components are sometimes called connected components.

The number of components in a given graph is an important graph invariant, and is closely related to invariants of matroids, topological spaces, and matrices. In random graphs, a frequently occurring phenomenon is the incidence of a giant component, one component that is significantly larger than the others; and of a percolation threshold, an edge probability above which a giant component exists and below which it does not.

The components of a graph can be constructed in linear time, and a special case of the problem, connected-component labeling, is a basic technique in image analysis. Dynamic connectivity algorithms maintain components as edges are inserted or deleted in a graph, in low time per change. In computational complexity theory, connected components have been used to study algorithms with limited space complexity, and sublinear time algorithms can accurately estimate the number of components.

Definitions and examples

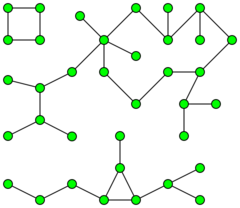

A component of a given undirected graph may be defined as a connected subgraph that is not part of any larger connected subgraph. For instance, the graph shown in the first illustration has three components. Every vertex of a graph belongs to one of the graph's components, which may be found as the induced subgraph of the set of vertices reachable from .[1] Every graph is the disjoint union of its components.[2] Additional examples include the following special cases:

- In an empty graph, each vertex forms a component with one vertex and zero edges.[3] More generally, a component of this type is formed for every isolated vertex in any graph.[4]

- In a connected graph, there is exactly one component: the whole graph.[4]

- In a forest, every component is a tree.[5]

- In a cluster graph, every component is a maximal clique. These graphs may be produced as the transitive closures of arbitrary undirected graphs, for which finding the transitive closure is an equivalent formulation of identifying the connected components.[6]

Another definition of components involves the equivalence classes of an equivalence relation defined on the graph's vertices. In an undirected graph, a vertex is reachable from a vertex if there is a path from to , or equivalently a walk (a path allowing repeated vertices and edges). Reachability is an equivalence relation, since:

- It is reflexive: There is a trivial path of length zero from any vertex to itself.

- It is symmetric: If there is a path from to , the same edges in the reverse order form a path from to .

- It is transitive: If there is a path from to and a path from to , the two paths may be concatenated together to form a walk from to .

The equivalence classes of this relation partition the vertices of the graph into disjoint sets, subsets of vertices that are all reachable from each other, with no additional reachable pairs outside of any of these subsets. Each vertex belongs to exactly one equivalence class. The components are then the induced subgraphs formed by each of these equivalence classes.[7] Alternatively, some sources define components as the sets of vertices rather than as the subgraphs they induce.[8]

Similar definitions involving equivalence classes have been used to defined components for other forms of graph connectivity, including the weak components[9] and strongly connected components of directed graphs[10] and the biconnected components of undirected graphs.[11]

Number of components

The number of components of a given finite graph can be used to count the number of edges in its spanning forests: In a graph with vertices and components, every spanning forest will have exactly edges. This number is the matroid-theoretic rank of the graph, and the rank of its graphic matroid. The rank of the dual cographic matroid equals the circuit rank of the graph, the minimum number of edges that must be removed from the graph to break all its cycles. In a graph with edges, vertices and components, the circuit rank is .[12]

A graph can be interpreted as a topological space in multiple ways, for instance by placing its vertices as points in general position in three-dimensional Euclidean space and representing its edges as line segments between those points.[13] The components of a graph can be generalized through these interpretations as the topological connected components of the corresponding space; these are equivalence classes of points that cannot be separated by pairs of disjoint closed sets. Just as the number of connected components of a topological space is an important topological invariant, the zeroth Betti number, the number of components of a graph is an important graph invariant, and in topological graph theory it can be interpreted as the zeroth Betti number of the graph.[3]

The number of components arises in other ways in graph theory as well. In algebraic graph theory it equals the multiplicity of 0 as an eigenvalue of the Laplacian matrix of a finite graph.[14] It is also the index of the first nonzero coefficient of the chromatic polynomial of the graph, and the chromatic polynomial of the whole graph can be obtained as the product of the polynomials of its components.[15] Numbers of components play a key role in the Tutte theorem characterizing finite graphs that have perfect matchings[16] and the associated Tutte–Berge formula for the size of a maximum matching,[17] and in the definition of graph toughness.[18]

Algorithms

It is straightforward to compute the components of a finite graph in linear time (in terms of the numbers of the vertices and edges of the graph) using either breadth-first search or depth-first search. In either case, a search that begins at some particular vertex will find the entire component containing (and no more) before returning. All components of a graph can be found by looping through its vertices, starting a new breadth-first or depth-first search whenever the loop reaches a vertex that has not already been included in a previously found component. (Hopcroft Tarjan) describe essentially this algorithm, and state that it was already "well known".[19]

Connected-component labeling, a basic technique in computer image analysis, involves the construction of a graph from the image and component analysis on the graph. The vertices are the subset of the pixels of the image, chosen as being of interest or as likely to be part of depicted objects. Edges connect adjacent pixels, with adjacency defined either orthogonally according to the Von Neumann neighborhood, or both orthogonally and diagonally according to the Moore neighborhood. Identifying the connected components of this graph allows additional processing to find more structure in those parts of the image or identify what kind of object is depicted. Researchers have developed component-finding algorithms specialized for this type of graph, allowing it to be processed in pixel order rather than in the more scattered order that would be generated by breadth-first or depth-first searching. This can be useful in situations where sequential access to the pixels is more efficient than random access, either because the image is represented in a hierarchical way that does not permit fast random access or because sequential access produces better memory access patterns.[20]

There are also efficient algorithms to dynamically track the components of a graph as vertices and edges are added, by using a disjoint-set data structure to keep track of the partition of the vertices into equivalence classes, replacing any two classes by their union when an edge connecting them is added. These algorithms take amortized time per operation, where adding vertices and edges and determining the component in which a vertex falls are both operations, and is a very slowly growing inverse of the very quickly growing Ackermann function.[21] One application of this sort of incremental connectivity algorithm is in Kruskal's algorithm for minimum spanning trees, which adds edges to a graph in sorted order by length and includes an edge in the minimum spanning tree only when it connects two different components of the previously-added subgraph.[22] When both edge insertions and edge deletions are allowed, dynamic connectivity algorithms can still maintain the same information, in amortized time per change and time per connectivity query,[23] or in near-logarithmic randomized expected time.[24]

Components of graphs have been used in computational complexity theory to study the power of Turing machines that have a working memory limited to a logarithmic number of bits, with the much larger input accessible only through read access rather than being modifiable. The problems that can be solved by machines limited in this way define the complexity class L. It was unclear for many years whether connected components could be found in this model, when formalized as a decision problem of testing whether two vertices belong to the same component, and in 1982 a related complexity class, SL, was defined to include this connectivity problem and any other problem equivalent to it under logarithmic-space reductions.[25] It was finally proven in 2008 that this connectivity problem can be solved in logarithmic space, and therefore that SL = L.[26]

In a graph represented as an adjacency list, with random access to its vertices, it is possible to estimate the number of connected components, with constant probability of obtaining additive (absolute) error at most , in sublinear time .[27]

In random graphs

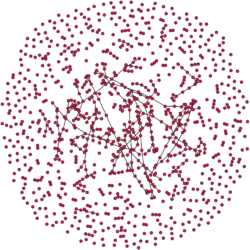

In random graphs the sizes of components are given by a random variable, which, in turn, depends on the specific model of how random graphs are chosen. In the version of the Erdős–Rényi–Gilbert model, a graph on vertices is generated by choosing randomly and independently for each pair of vertices whether to include an edge connecting that pair, with probability of including an edge and probability of leaving those two vertices without an edge connecting them.[28] The connectivity of this model depends on , and there are three different ranges of with very different behavior from each other. In the analysis below, all outcomes occur with high probability, meaning that the probability of the outcome is arbitrarily close to one for sufficiently large values of . The analysis depends on a parameter , a positive constant independent of that can be arbitrarily close to zero.

- Subcritical

- In this range of , all components are simple and very small. The largest component has logarithmic size. The graph is a pseudoforest. Most of its components are trees: the number of vertices in components that have cycles grows more slowly than any unbounded function of the number of vertices. Every tree of fixed size occurs linearly many times.[29]

- Critical

- The largest connected component has a number of vertices proportional to . There may exist several other large components; however, the total number of vertices in non-tree components is again proportional to .[30]

- Supercritical

- There is a single giant component containing a linear number of vertices. For large values of its size approaches the whole graph: where is the positive solution to the equation . The remaining components are small, with logarithmic size.[31]

In the same model of random graphs, there will exist multiple connected components with high probability for values of below a significantly higher threshold, , and a single connected component for values above the threshold, . This phenomenon is closely related to the coupon collector's problem: in order to be connected, a random graph needs enough edges for each vertex to be incident to at least one edge. More precisely, if random edges are added one by one to a graph, then with high probability the first edge whose addition connects the whole graph touches the last isolated vertex.[32]

For different models including the random subgraphs of grid graphs, the connected components are described by percolation theory. A key question in this theory is the existence of a percolation threshold, a critical probability above which a giant component (or infinite component) exists and below which it does not.[33]

References

- ↑ Clark, John; Holton, Derek Allan (1995), A First Look at Graph Theory, Allied Publishers, p. 28, ISBN 9788170234630, https://books.google.com/books?id=kb-aLlgYZuEC&pg=PA28, retrieved 2022-01-07

- ↑ Joyner, David; Nguyen, Minh Van; Phillips, David (May 10, 2013), "1.6.1 Union, intersection, and join", Algorithmic Graph Theory and Sage (0.8-r1991 ed.), Google, pp. 34–35, https://code.google.com/p/graphbook/, retrieved January 8, 2022

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Tutte, W. T. (1984), Graph Theory, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, 21, Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, p. 15, ISBN 0-201-13520-5, https://books.google.com/books?id=uTGhooU37h4C&pg=PA15, retrieved 2022-01-07

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Thulasiraman, K.; Swamy, M. N. S. (2011), Graphs: Theory and Algorithms, John Wiley & Sons, p. 9, ISBN 978-1-118-03025-7, https://books.google.com/books?id=rFH7eQffQNkC&pg=PA9, retrieved 2022-01-07

- ↑ Bollobás, Béla (1998), Modern Graph Theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 184, New York: Springer-Verlag, p. 6, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0619-4, ISBN 0-387-98488-7, https://books.google.com/books?id=JeIlBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA6, retrieved 2022-01-08

- ↑ McColl, W. F.; Noshita, K. (1986), "On the number of edges in the transitive closure of a graph", Discrete Applied Mathematics 15 (1): 67–73, doi:10.1016/0166-218X(86)90020-X

- ↑ Foldes, Stephan (2011), Fundamental Structures of Algebra and Discrete Mathematics, John Wiley & Sons, p. 199, ISBN 978-1-118-03143-8, https://books.google.com/books?id=A59RivXPMzkC&pg=PA199, retrieved 2022-01-07

- ↑ Siek, Jeremy; Lee, Lie-Quan; Lumsdaine, Andrew (2001), "7.1 Connected components: Definitions", The Boost Graph Library: User Guide and Reference Manual, Addison-Wesley, pp. 97–98

- ↑ Knuth, Donald E. (January 15, 2022), "Weak components", The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 4, Pre-Fascicle 12A: Components and Traversal, pp. 11–14, https://cs.stanford.edu/~knuth/fasc12a+.pdf, retrieved March 1, 2022

- ↑ Lewis, Harry; Zax, Rachel (2019), Essential Discrete Mathematics for Computer Science, Princeton University Press, p. 145, ISBN 978-0-691-19061-7, https://books.google.com/books?id=fAZ-DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA145, retrieved 2022-01-08

- ↑ Kozen, Dexter C. (1992), "4.1 Biconnected components", The Design and Analysis of Algorithms, Texts and Monographs in Computer Science, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 20–22, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-4400-4, ISBN 0-387-97687-6, https://books.google.com/books?id=HFn1BwAAQBAJ&pg=PA20, retrieved 2022-01-08

- ↑ "An introduction to matroid theory", The American Mathematical Monthly 80 (5): 500–525, 1973, doi:10.1080/00029890.1973.11993318

- ↑ Wood, David R. (2014), "Three-dimensional graph drawing", in Kao, Ming-Yang, Encyclopedia of Algorithms, Springer, pp. 1–7, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-27848-8_656-1, https://users.monash.edu/~davidwo/papers/EncPaper.pdf, retrieved 2022-01-08

- ↑ Cioabă, Sebastian M. (2011), "Some applications of eigenvalues of graphs", in Dehmer, Matthias, Structural Analysis of Complex Networks, New York: Birkhäuser/Springer, pp. 357–379, doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-4789-6_14; see proof of Lemma 5, p. 361

- ↑ "An introduction to chromatic polynomials", Journal of Combinatorial Theory 4: 52–71, 1968, doi:10.1016/S0021-9800(68)80087-0; see Theorem 2, p. 59, and corollary, p. 65

- ↑ "The factorization of linear graphs", The Journal of the London Mathematical Society 22 (2): 107–111, 1947, doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-22.2.107

- ↑ "Sur le couplage maximum d'un graphe", Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences 247: 258–259, 1958

- ↑ "Tough graphs and Hamiltonian circuits", Discrete Mathematics 5 (3): 215–228, 1973, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(73)90138-6

- ↑ "Algorithm 447: efficient algorithms for graph manipulation", Communications of the ACM 16 (6): 372–378, June 1973, doi:10.1145/362248.362272

- ↑ Dillencourt, Michael B. (1992), "A general approach to connected-component labeling for arbitrary image representations", Journal of the ACM 39 (2): 253–280, doi:10.1145/128749.128750

- ↑ Bengelloun, Safwan Abdelmajid (December 1982), Aspects of Incremental Computing, Yale University, p. 12, ProQuest 303248045

- ↑ Skiena, Steven (2008), "6.1.2 Kruskal's Algorithm", The Algorithm Design Manual, Springer, pp. 196–198, doi:10.1007/978-1-84800-070-4, ISBN 978-1-84800-069-8, Bibcode: 2008adm..book.....S, https://books.google.com/books?id=7XUSn0IKQEgC&pg=PA196, retrieved 2022-01-07

- ↑ Wulff-Nilsen, Christian (2013), "Faster deterministic fully-dynamic graph connectivity", in Khanna, Sanjeev, Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, SODA 2013, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, January 6-8, 2013, pp. 1757–1769, doi:10.1137/1.9781611973105.126

- ↑ Huang, Shang-En; Huang, Dawei; Kopelowitz, Tsvi; Pettie, Seth (2017), "Fully dynamic connectivity in amortized expected time", in Klein, Philip N., Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, SODA 2017, Barcelona, Spain, Hotel Porta Fira, January 16-19, pp. 510–520, doi:10.1137/1.9781611974782.32

- ↑ "Symmetric space-bounded computation", Theoretical Computer Science 19 (2): 161–187, 1982, doi:10.1016/0304-3975(82)90058-5

- ↑ "Undirected connectivity in log-space", Journal of the ACM 55 (4): A17:1–A17:24, 2008, doi:10.1145/1391289.1391291

- ↑ Berenbrink, Petra; Krayenhoff, Bruce; Mallmann-Trenn, Frederik (2014), "Estimating the number of connected components in sublinear time", Information Processing Letters 114 (11): 639–642, doi:10.1016/j.ipl.2014.05.008

- ↑ "1.1 Models and relationships", Introduction to Random Graphs, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2016, pp. 3–9, doi:10.1017/CBO9781316339831, ISBN 978-1-107-11850-8

- ↑ (Frieze Karoński), 2.1 Sub-critical phase, pp. 20–33; see especially Theorem 2.8, p. 26, Theorem 2.9, p. 28, and Lemma 2.11, p. 29

- ↑ (Frieze Karoński), 2.3 Phase transition, pp. 39–45

- ↑ (Frieze Karoński), 2.2 Super-critical phase, pp. 33; see especially Theorem 2.14, p. 33–39

- ↑ (Frieze Karoński), 4.1 Connectivity, pp. 64–68

- ↑ Cohen, Reuven; Havlin, Shlomo (2010), "10.1 Percolation on complex networks: Introduction", Complex Networks: Structure, Robustness and Function, Cambridge University Press, pp. 97–98, ISBN 978-1-139-48927-0, https://books.google.com/books?id=1ECLiFrKulIC&pg=PA97, retrieved 2022-01-10

External links

- MATLAB code to find components in undirected graphs, MATLAB File Exchange.

- Connected components, Steven Skiena, The Stony Brook Algorithm Repository

|