Gumbel distribution

|

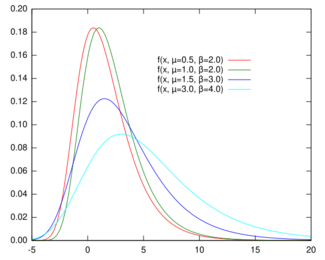

Probability density function  | |||

|

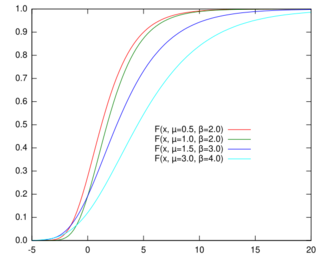

Cumulative distribution function  | |||

| Notation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters |

location (real) scale (real) | ||

| Support | |||

|

where | |||

| CDF | |||

| Quantile | |||

| Mean |

where is the Euler–Mascheroni constant | ||

| Median | |||

| Mode | |||

| Variance | |||

| Skewness | |||

| Kurtosis | |||

| Entropy | |||

| MGF | |||

| CF | |||

In probability theory and statistics, the Gumbel distribution (also known as the type-I generalized extreme value distribution) is used to model the distribution of the maximum (or the minimum) of a number of samples of various distributions.

This distribution might be used to represent the distribution of the maximum level of a river in a particular year if there was a list of maximum values for the past ten years. It is useful in predicting the chance that an extreme earthquake, flood or other natural disaster will occur. The potential applicability of the Gumbel distribution to represent the distribution of maxima relates to extreme value theory, which indicates that it is likely to be useful if the distribution of the underlying sample data is of the normal or exponential type.[lower-alpha 1]

The Gumbel distribution is a particular case of the generalized extreme value distribution (also known as the Fisher–Tippett distribution). It is also known as the log-Weibull distribution and the double exponential distribution (a term that is alternatively sometimes used to refer to the Laplace distribution). It is related to the Gompertz distribution: when its density is first reflected about the origin and then restricted to the positive half line, a Gompertz function is obtained.

In the latent variable formulation of the multinomial logit model — common in discrete choice theory — the errors of the latent variables follow a Gumbel distribution. This is useful because the difference of two Gumbel-distributed random variables has a logistic distribution.

The Gumbel distribution is named after Emil Julius Gumbel (1891–1966), based on his original papers describing the distribution.[1][2]

Definitions

The cumulative distribution function of the Gumbel distribution is

Standard Gumbel distribution

The standard Gumbel distribution is the case where and with cumulative distribution function

and probability density function

In this case the mode is 0, the median is , the mean is (the Euler–Mascheroni constant), and the standard deviation is

The cumulants, for n > 1, are given by

Properties

The mode is μ, while the median is and the mean is given by

- ,

where is the Euler–Mascheroni constant.

The standard deviation is hence [3]

At the mode, where , the value of becomes , irrespective of the value of

If are iid Gumbel random variables with parameters then is also a Gumbel random variable with parameters .

If are iid random variables such that has the same distribution as for all natural numbers , then is necessarily Gumbel distributed with scale parameter (actually it suffices to consider just two distinct values of k>1 which are coprime).

Related distributions

The discrete Gumbel distribution

Many problems in discrete mathematics involve the study of an extremal parameter that follows a discrete version of the Gumbel distribution.[4][5] This discrete version is the law of , where follows the continuous Gumbel distribution . Accordingly, this gives for any .

Denoting as the discrete version, one has and .

There is no known closed form for the mean, variance (or higher-order moments) of the discrete Gumbel distribution, but it is easy to obtain high-precision numerical evaluations via rapidly converging infinite sums. For example, this yields , but it remains an open problem to find a closed form for this constant (it is plausible there is none).

Aguech, Althagafi, and Banderier[4] provide various bounds linking the discrete and continuous versions of the Gumbel distribution and explicitly detail (using methods from Mellin transform) the oscillating phenomena that appear when one has a sequence of random variables converging to a discrete Gumbel distribution.

Continuous distributions

- If has a Gumbel distribution, then the conditional distribution of given that is positive, or equivalently given that is negative, has a Gompertz distribution. The cdf of is related to , the cdf of , by the formula for . Consequently, the densities are related by : the Gompertz density is proportional to a reflected Gumbel density, restricted to the positive half-line.[6]

- If is an exponentially distributed variable with mean 1, then .

- If is a uniformly distributed variable on the unit interval, then .

- If and are independent, then (see Logistic distribution).

- Despite this, if are independent, then . This can easily be seen by noting that (where is the Euler-Mascheroni constant). Instead, the distribution of linear combinations of independent Gumbel random variables can be approximated by GNIG and GIG distributions.[7]

Theory related to the generalized multivariate log-gamma distribution provides a multivariate version of the Gumbel distribution.

Occurrence and applications

Applications of the continuous Gumbel distribution

Gumbel has shown that the maximum value (or last order statistic) in a sample of random variables following an exponential distribution minus the natural logarithm of the sample size [9] approaches the Gumbel distribution as the sample size increases.[10]

Concretely, let be the probability distribution of and its cumulative distribution. Then the maximum value out of realizations of is smaller than if and only if all realizations are smaller than . So the cumulative distribution of the maximum value satisfies

and, for large , the right-hand-side converges to

In hydrology, therefore, the Gumbel distribution is used to analyze such variables as monthly and annual maximum values of daily rainfall and river discharge volumes,[3] and also to describe droughts.[11]

Gumbel has also shown that the estimator r⁄(n+1) for the probability of an event — where r is the rank number of the observed value in the data series and n is the total number of observations — is an unbiased estimator of the cumulative probability around the mode of the distribution. Therefore, this estimator is often used as a plotting position.

Prediction

- It is often of interest to predict probabilities out-of-sample data under the assumption that both the training data and the out-of-sample data follow a Gumbel distribution.

- Predictions of probabilities generated by substituting maximum likelihood estimates of the Gumbel parameters into the cumulative distribution function ignore parameter uncertainty. As a result, the probabilities are not well calibrated, do not reflect the frequencies of out-of-sample events, and, in particular, underestimate the probabilities of out-of-sample tail events.[12]

- Predictions generated using the objective Bayesian approach of calibrating prior prediction completely eliminate this underestimation. The Gumbel distribution is one of a number of statistical distributions with group structure, which arises because the Gumbel is a location-scale model. As a result of the group structure, the Gumbel has associated left and right Haar measures. The use of the right Haar measure as the prior (known as the right Haar prior) in a Bayesian prediction gives probabilities that are perfectly calibrated, for any underlying true parameter values.[13][12][14] Calibrating prior prediction for the Gumbel using the appropriate right Haar prior is implemented in the R software package fitdistcp.[15]

Occurrences of the discrete Gumbel distribution

In combinatorics, the discrete Gumbel distribution appears as a limiting distribution for the hitting time in the coupon collector's problem. This result was first established by Laplace in 1812 in his Théorie analytique des probabilités, marking the first historical occurrence of what would later be called the Gumbel distribution.

In number theory, the Gumbel distribution approximates the number of terms in a random partition of an integer[16] as well as the trend-adjusted sizes of maximal prime gaps and maximal gaps between prime constellations.[17]

In probability theory, it appears as the distribution of the maximum height reached by discrete walks (on the lattice ), where the process can be reset to its starting point at each step.[4]

In analysis of algorithms, it appears, for example, in the study of the maximum carry propagation in base- addition algorithms.[18]

Random variate generation

Since the quantile function (inverse cumulative distribution function), , of a Gumbel distribution is given by

the variate has a Gumbel distribution with parameters and when the random variate is drawn from the uniform distribution on the interval .

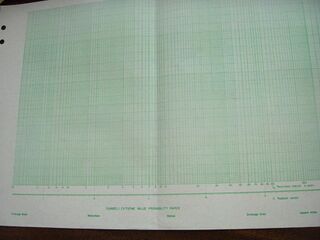

Probability paper

In pre-software times probability paper was used to picture the Gumbel distribution (see illustration). The paper is based on linearization of the cumulative distribution function :

In the paper the horizontal axis is constructed at a double log scale. The vertical axis is linear. By plotting on the horizontal axis of the paper and the -variable on the vertical axis, the distribution is represented by a straight line with a slope 1. When distribution fitting software like CumFreq became available, the task of plotting the distribution was made easier.

Gumbel reparameterization tricks

In machine learning, the Gumbel distribution is sometimes employed to generate samples from the categorical distribution. This technique is called "Gumbel-max trick" and is a special example of "reparameterization tricks".[19]

In detail, let be nonnegative, and not all zero, and let be independent samples of Gumbel(0, 1), then by routine integration,That is,

Equivalently, given any , we can sample from its Boltzmann distribution by

Related equations include:[20]

- If , then .

- .

- . That is, the Gumbel distribution is a max-stable distribution family.

See also

- Type-2 Gumbel distribution

- Extreme value theory

- Generalized extreme value distribution

- Fisher–Tippett–Gnedenko theorem

- Emil Julius Gumbel

Notes

- ↑ This article uses the Gumbel distribution to model the distribution of the maximum value. To model the minimum value, use the negative of the original values.

References

- ↑ Gumbel, E.J. (1935), "Les valeurs extrêmes des distributions statistiques", Annales de l'Institut Henri Poincaré 5 (2): 115–158, http://archive.numdam.org/article/AIHP_1935__5_2_115_0.pdf

- ↑ Gumbel E.J. (1941). "The return period of flood flows". The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 12, 163–190.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Oosterbaan, R.J. (1994). "Chapter 6 Frequency and Regression Analysis". in Ritzema, H.P.. Drainage Principles and Applications, Publication 16. Wageningen, The Netherlands: International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement (ILRI). pp. 175–224. ISBN 90-70754-33-9. http://www.waterlog.info/pdf/freqtxt.pdf.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Aguech, R.; Althagafi, A.; Banderier, C. (2023), "Height of walks with resets, the Moran model, and the discrete Gumbel distribution", Séminaire Lotharingien de Combinatoire 87B (12): 1–37

- ↑ Analytic Combinatorics, Flajolet and Sedgewick.

- ↑ Willemse, W.J.; Kaas, R. (2007). "Rational reconstruction of frailty-based mortality models by a generalisation of Gompertz' law of mortality". Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 40 (3): 468. doi:10.1016/j.insmatheco.2006.07.003. https://www.dnb.nl/binaries/Working%20Paper%20135-2007_tcm46-146792.pdf. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ↑ Marques, F.; Coelho, C.; de Carvalho, M. (2015). "On the distribution of linear combinations of independent Gumbel random variables". Statistics and Computing 25 (3): 683‒701. doi:10.1007/s11222-014-9453-5. https://www.maths.ed.ac.uk/~mdecarv/papers/marques2015.pdf.

- ↑ "CumFreq, distribution fitting of probability, free calculator". https://www.waterlog.info/cumfreq.htm.

- ↑ "Gumbel distribution and exponential distribution". https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/3527556/gumbel-distribution-and-exponential-distribution?noredirect=1#comment7669633_3527556.

- ↑ Gumbel, E.J. (1954). Statistical theory of extreme values and some practical applications. Applied Mathematics Series. 33 (1st ed.). U.S. Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards. https://ntrl.ntis.gov/NTRL/dashboard/searchResults/titleDetail/PB175818.xhtml.

- ↑ Burke, Eleanor J.; Perry, Richard H.J.; Brown, Simon J. (2010). "An extreme value analysis of UK drought and projections of change in the future". Journal of Hydrology 388 (1–2): 131–143. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2010.04.035. Bibcode: 2010JHyd..388..131B.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Jewson, Stephen; Sweeting, Trevor; Jewson, Lynne (2025-02-20). "Reducing reliability bias in assessments of extreme weather risk using calibrating priors" (in English). Advances in Statistical Climatology, Meteorology and Oceanography 11 (1): 1–22. doi:10.5194/ascmo-11-1-2025. ISSN 2364-3579. Bibcode: 2025ASCMO..11....1J. https://ascmo.copernicus.org/articles/11/1/2025/.

- ↑ Severini, Thomas A.; Mukerjee, Rahul; Ghosh, Malay (2002-12-01). "On an exact probability matching property of right-invariant priors". Biometrika 89 (4): 952–957. doi:10.1093/biomet/89.4.952. ISSN 0006-3444. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/89.4.952.

- ↑ Gerrard, R.; Tsanakas, A. (2011). "Failure Probability Under Parameter Uncertainty" (in en). Risk Analysis 31 (5): 727–744. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01549.x. ISSN 1539-6924. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01549.x.

- ↑ Jewson, Stephen (2025-04-23), fitdistcp: Distribution Fitting with Calibrating Priors for Commonly Used Distributions, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/fitdistcp/index.html, retrieved 2025-07-26

- ↑ Erdös, Paul; Lehner, Joseph (1941). "The distribution of the number of summands in the partitions of a positive integer". Duke Mathematical Journal 8 (2): 335. doi:10.1215/S0012-7094-41-00826-8.

- ↑ Kourbatov, A. (2013). "Maximal gaps between prime k-tuples: a statistical approach". Journal of Integer Sequences 16. Bibcode: 2013arXiv1301.2242K. Article 13.5.2.

- ↑ Knuth, Donald E. (1978), "The average time for carry propagation", Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen. Proceedings. Series A. Indagationes Mathematicae 81: 238–242

- ↑ Jang, Eric; Gu, Shixiang; Poole, Ben (April 2017). "Categorical Reparameterization with Gumble-Softmax". International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) 2017. https://pure.mpg.de/pubman/faces/ViewItemOverviewPage.jsp?itemId=item_2564872.

- ↑ Balog, Matej; Tripuraneni, Nilesh; Ghahramani, Zoubin; Weller, Adrian (2017-07-17). "Lost Relatives of the Gumbel Trick" (in en). International Conference on Machine Learning (PMLR): 371–379. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v70/balog17a.html.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

|