Lift (mathematics)

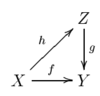

In category theory, a branch of mathematics, given a morphism f: X → Y and a morphism g: Z → Y, a lift or lifting of f to Z is a morphism h: X → Z such that f = g∘h. We say that f factors through h.

A basic example in topology is lifting a path in one topological space to a path in a covering space.[1] For example, consider mapping opposite points on a sphere to the same point, a continuous map from the sphere covering the projective plane. A path in the projective plane is a continuous map from the unit interval [0,1]. We can lift such a path to the sphere by choosing one of the two sphere points mapping to the first point on the path, then maintain continuity. In this case, each of the two starting points forces a unique path on the sphere, the lift of the path in the projective plane. Thus in the category of topological spaces with continuous maps as morphisms, we have

Lifts are ubiquitous; for example, the definition of fibrations (see Homotopy lifting property) and the valuative criteria of separated and proper maps of schemes are formulated in terms of existence and (in the last case) uniqueness of certain lifts.

In algebraic topology and homological algebra, tensor product and the Hom functor are adjoint; however, they might not always lift to an exact sequence. This leads to the definition of the Ext functor and the Tor functor.

Algebraic logic

The notations of first-order predicate logic are streamlined when quantifiers are relegated to established domains and ranges of binary relations. Gunther Schmidt and Michael Winter have illustrated the method of lifting traditional logical expressions of topology to calculus of relations in their book Relational Topology.[2] They aim "to lift concepts to a relational level making them point free as well as quantifier free, thus liberating them from the style of first order predicate logic and approaching the clarity of algebraic reasoning."

For example, a partial function M corresponds to the inclusion where denotes the identity relation on the range of M. "The notation for quantification is hidden and stays deeply incorporated in the typing of the relational operations (here transposition and composition) and their rules."

Circle maps

For maps of a circle, the definition of a lift to the real line is slightly different (a common application is the calculation of rotation number). Given a map on a circle, , a lift of , , is any map on the real line, , for which there exists a projection (or, covering map), , such that .[3]

See also

- Covering space

- Projective module

- Formally smooth map satisfies an infinitesimal lifting property.

- Lifting property in categories

- Monsky–Washnitzer cohomology lifts p-adic varieties to characteristic zero.

- SBI ring allows idempotents to be lifted above the Jacobson radical.

- Ikeda lift

- Miyawaki lift of Siegel modular forms

- Saito–Kurokawa lift of modular forms

- Rotation number uses a lift of a homeomorphism of the circle to the real line.

- Arithmetic geometry: Andrew Wiles (1995) modularity lifting

- Hensel's lemma

- Monad (functional programming) uses map functional to lift simple operators to monadic form.

- Tangent bundle § Lifts

References

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Marquis (2006) "A path to Epistemology of Mathematics: Homotopy theory", pages 239 to 260 in The Architecture of Modern Mathematics, J. Ferreiros & J.J. Gray, editors, Oxford University Press ISBN 978-0-19-856793-6

- ↑ Gunther Schmidt and Michael Winter (2018): Relational Topology, page 2 to 5, Lecture Notes in Mathematics vol. 2208, Springer books, ISBN 978-3-319-74451-3

- ↑ Robert L. Devaney (1989): An Introduction to Chaotic Dynamical Systems, pp. 102-103, Addison-Wesley

|