Physics:Two-body Dirac equations

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

|

| History |

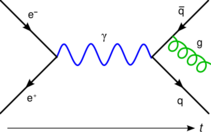

In quantum field theory, and in the significant subfields of quantum electrodynamics (QED) and quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the two-body Dirac equations (TBDE) of constraint dynamics provide a three-dimensional yet manifestly covariant reformulation of the Bethe–Salpeter equation[1] for two spin-1/2 particles. Such a reformulation is necessary since without it, as shown by Nakanishi,[2] the Bethe–Salpeter equation possesses negative-norm solutions arising from the presence of an essentially relativistic degree of freedom, the relative time. These "ghost" states have spoiled the naive interpretation of the Bethe–Salpeter equation as a quantum mechanical wave equation. The two-body Dirac equations of constraint dynamics rectify this flaw. The forms of these equations can not only be derived from quantum field theory [3][4] they can also be derived purely in the context of Dirac's constraint dynamics [5][6] and relativistic mechanics and quantum mechanics.[7][8][9][10] Their structures, unlike the more familiar two-body Dirac equation of Breit,[11][12][13] which is a single equation, are that of two simultaneous quantum relativistic wave equations. A single two-body Dirac equation similar to the Breit equation can be derived from the TBDE.[14] Unlike the Breit equation, it is manifestly covariant and free from the types of singularities that prevent a strictly nonperturbative treatment of the Breit equation.[15] In applications of the TBDE to QED, the two particles interact by way of four-vector potentials derived from the field theoretic electromagnetic interactions between the two particles. In applications to QCD, the two particles interact by way of four-vector potentials and Lorentz invariant scalar interactions, derived in part from the field theoretic chromomagnetic interactions between the quarks and in part by phenomenological considerations. As with the Breit equation a sixteen-component spinor Ψ is used.

Equations

For QED, each equation has the same structure as the ordinary one-body Dirac equation in the presence of an external electromagnetic field, given by the 4-potential . For QCD, each equation has the same structure as the ordinary one-body Dirac equation in the presence of an external field similar to the electromagnetic field and an additional external field given by in terms of a Lorentz invariant scalar . In natural units:[16] those two-body equations have the form.

where, in coordinate space, pμ is the 4-momentum, related to the 4-gradient by (the metric used here is ) and γμ are the gamma matrices. The two-body Dirac equations (TBDE) have the property that if one of the masses becomes very large, say then the 16-component Dirac equation reduces to the 4-component one-body Dirac equation for particle one in an external potential.

In SI units: where c is the speed of light and

Natural units will be used below. A tilde symbol is used over the two sets of potentials to indicate that they may have additional gamma matrix dependencies not present in the one-body Dirac equation. Any coupling constants such as the electron charge are embodied in the vector potentials.

Constraint dynamics and the TBDE

Constraint dynamics applied to the TBDE requires a particular form of mathematical consistency: the two Dirac operators must commute with each other. This is plausible if one views the two equations as two compatible constraints on the wave function. (See the discussion below on constraint dynamics.) If the two operators did not commute, (as, e.g., with the coordinate and momentum operators ) then the constraints would not be compatible (one could not e.g., have a wave function that satisfied both and ). This mathematical consistency or compatibility leads to three important properties of the TBDE. The first is a condition that eliminates the dependence on the relative time in the center of momentum (c.m.) frame defined by . (The variable is the total energy in the c.m. frame.) Stated another way, the relative time is eliminated in a covariant way. In particular, for the two operators to commute, the scalar and four-vector potentials can depend on the relative coordinate only through its component orthogonal to in which

This implies that in the c.m. frame , which has zero time component.

Secondly, the mathematical consistency condition also eliminates the relative energy in the c.m. frame. It does this by imposing on each Dirac operator a structure such that in a particular combination they lead to this interaction independent form, eliminating in a covariant way the relative energy.

In this expression is the relative momentum having the form for equal masses. In the c.m. frame (), the time component of the relative momentum, that is the relative energy, is thus eliminated. in the sense that .

A third consequence of the mathematical consistency is that each of the world scalar and four vector potentials has a term with a fixed dependence on and in addition to the gamma matrix independent forms of and which appear in the ordinary one-body Dirac equation for scalar and vector potentials. These extra terms correspond to additional recoil spin-dependence not present in the one-body Dirac equation and vanish when one of the particles becomes very heavy (the so-called static limit).

More on constraint dynamics: generalized mass shell constraints

Constraint dynamics arose from the work of Dirac [6] and Bergmann.[17] This section shows how the elimination of relative time and energy takes place in the c.m. system for the simple system of two relativistic spinless particles. Constraint dynamics was first applied to the classical relativistic two particle system by Todorov,[18][19] Kalb and Van Alstine,[20][21] Komar,[22][23] and Droz–Vincent.[24] With constraint dynamics, these authors found a consistent and covariant approach to relativistic canonical Hamiltonian mechanics that also evades the Currie–Jordan–Sudarshan "No Interaction" theorem.[25][26] That theorem states that without fields, one cannot have a relativistic Hamiltonian dynamics. Thus, the same covariant three-dimensional approach which allows the quantized version of constraint dynamics to remove quantum ghosts simultaneously circumvents at the classical level the C.J.S. theorem. Consider a constraint on the otherwise independent coordinate and momentum four vectors, written in the form . The symbol is called a weak equality and implies that the constraint is to be imposed only after any needed Poisson brackets are performed. In the presence of such constraints, the total Hamiltonian is obtained from the Lagrangian by adding to the Legendre Hamiltonian the sum of the constraints times an appropriate set of Lagrange multipliers .

This total Hamiltonian is traditionally called the Dirac Hamiltonian. Constraints arise naturally from parameter invariant actions of the form

In the case of four vector and Lorentz scalar interactions for a single particle the Lagrangian is

The canonical momentum is and by squaring leads to the generalized mass shell condition or generalized mass shell constraint

Since, in this case, the Legendre Hamiltonian vanishes the Dirac Hamiltonian is simply the generalized mass constraint (with no interactions it would simply be the ordinary mass shell constraint)

One then postulates that for two bodies the Dirac Hamiltonian is the sum of two such mass shell constraints, that is and that each constraint be constant in the proper time associated with

Here the weak equality means that the Poisson bracket could result in terms proportional one of the constraints, the classical Poisson brackets for the relativistic two-body system being defined by

To see the consequences of having each constraint be a constant of the motion, take, for example

Since and and one has

The simplest solution to this is which leads to (note the equality in this case is not a weak one in that no constraint need be imposed after the Poisson bracket is worked out) (see Todorov,[19] and Wong and Crater [27] ) with the same defined above.

Quantization

In addition to replacing classical dynamical variables by their quantum counterparts, quantization of the constraint mechanics takes place by replacing the constraint on the dynamical variables with a restriction on the wave function

The first set of equations for i = 1, 2 play the role for spinless particles that the two Dirac equations play for spin-one-half particles. The classical Poisson brackets are replaced by commutators

Thus and we see in this case that the constraint formalism leads to the vanishing commutator of the wave operators for the two particles. This is the analogue of the claim stated earlier that the two Dirac operators commute with one another.

Covariant elimination of the relative energy

The vanishing of the above commutator ensures that the dynamics is independent of the relative time in the c.m. frame. In order to covariantly eliminate the relative energy, introduce the relative momentum defined by

-

()

-

()

The above definition of the relative momentum forces the orthogonality of the total momentum and the relative momentum, which follows from taking the scalar product of either equation with . From Eqs.(1) and (2), this relative momentum can be written in terms of and as

where are the projections of the momenta and along the direction of the total momentum . Subtracting the two constraints and , gives

-

()

Thus on these states

The equation describes both the c.m. motion and the internal relative motion. To characterize the former motion, observe that since the potential depends only on the difference of the two coordinates

(This does not require that since the .) Thus, the total momentum is a constant of motion and is an eigenstate state characterized by a total momentum . In the c.m. system with the invariant center of momentum (c.m.) energy. Thus

-

()

and so is also an eigenstate of c.m. energy operators for each of the two particles,

The relative momentum then satisfies so that

The above set of equations follow from the constraints and the definition of the relative momenta given in Eqs.(1) and (2). If instead one chooses to define (for a more general choice see Horwitz),[28] independent of the wave function, then

-

()

-

()

and it is straight forward to show that the constraint Eq.(3) leads directly to:

-

()

in place of . This conforms with the earlier claim on the vanishing of the relative energy in the c.m. frame made in conjunction with the TBDE. In the second choice the c.m. value of the relative energy is not defined as zero but comes from the original generalized mass shell constraints. The above equations for the relative and constituent four-momentum are the relativistic analogues of the non-relativistic equations

Covariant eigenvalue equation for internal motion

Using Eqs.(5),(6),(7), one can write in terms of and

-

()

where

Eq.(8) contains both the total momentum [through the ] and the relative momentum . Using Eq. (4), one obtains the eigenvalue equation

-

()

so that becomes the standard triangle function displaying exact relativistic two-body kinematics:

With the above constraint Eqs.(7) on then where . This allows writing Eq. (9) in the form of an eigenvalue equation

having a structure very similar to that of the ordinary three-dimensional nonrelativistic Schrödinger equation. It is a manifestly covariant equation, but at the same time its three-dimensional structure is evident. The four-vectors and have only three independent components since The similarity to the three-dimensional structure of the nonrelativistic Schrödinger equation can be made more explicit by writing the equation in the c.m. frame in which

Comparison of the resultant form

-

()

with the time independent Schrödinger equation

-

()

makes this similarity explicit.

The two-body relativistic Klein–Gordon equations

A plausible structure for the quasipotential can be found by observing that the one-body Klein–Gordon equation takes the form when one introduces a scalar interaction and timelike vector interaction via and . In the two-body case, separate classical [29][30] and quantum field theory [4] arguments show that when one includes world scalar and vector interactions then depends on two underlying invariant functions and through the two-body Klein–Gordon-like potential form with the same general structure, that is Those field theories further yield the c.m. energy dependent forms and ones that Tododov introduced as the relativistic reduced mass and effective particle energy for a two-body system. Similar to what happens in the nonrelativistic two-body problem, in the relativistic case we have the motion of this effective particle taking place as if it were in an external field (here generated by and ). The two kinematical variables and are related to one another by the Einstein condition If one introduces the four-vectors, including a vector interaction and scalar interaction , then the following classical minimal constraint form reproduces

-

()

Notice, that the interaction in this "reduced particle" constraint depends on two invariant scalars, and , one guiding the time-like vector interaction and one the scalar interaction.

Is there a set of two-body Klein–Gordon equations analogous to the two-body Dirac equations? The classical relativistic constraints analogous to the quantum two-body Dirac equations (discussed in the introduction) and that have the same structure as the above Klein–Gordon one-body form are Defining structures that display time-like vector and scalar interactions gives Imposing and using the constraint , reproduces Eqs.(12) provided

The corresponding Klein–Gordon equations are and each, due to the constraint is equivalent to

Hyperbolic versus external field form of the two-body Dirac equations

For the two body system there are numerous covariant forms of interaction. The simplest way of looking at these is from the point of view of the gamma matrix structures of the corresponding interaction vertices of the single particle exchange diagrams. For scalar, pseudoscalar, vector, pseudovector, and tensor exchanges those matrix structures are respectively in which The form of the Two-Body Dirac equations which most readily incorporates each or any number of these intereractions in concert is the so-called hyperbolic form of the TBDE.[31] For combined scalar and vector interactions those forms ultimately reduce to the ones given in the first set of equations of this article. Those equations are called the external field-like forms because their appearances are individually the same as those for the usual one-body Dirac equation in the presence of external vector and scalar fields.

The most general hyperbolic form for compatible TBDE is

-

()

where represents any invariant interaction singly or in combination. It has a matrix structure in addition to coordinate dependence. Depending on what that matrix structure is one has either scalar, pseudoscalar, vector, pseudovector, or tensor interactions. The operators and are auxiliary constraints satisfying

-

()

in which the are the free Dirac operators

-

()

This, in turn leads to the two compatibility conditions and provided that These compatibility conditions do not restrict the gamma matrix structure of . That matrix structure is determined by the type of vertex-vertex structure incorporated in the interaction. For the two types of invariant interactions emphasized in this article they are

For general independent scalar and vector interactions The vector interaction specified by the above matrix structure for an electromagnetic-like interaction would correspond to the Feynman gauge.

If one inserts Eq.(14) into (13) and brings the free Dirac operator (15) to the right of the matrix hyperbolic functions and uses standard gamma matrix commutators and anticommutators and one arrives at

-

()

in which The (covariant) structure of these equations are analogous to those of a Dirac equation for each of the two particles, with and playing the roles that and do in the single particle Dirac equation Over and above the usual kinetic part and time-like vector and scalar potential portions, the spin-dependent modifications involving and the last set of derivative terms are two-body recoil effects absent for the one-body Dirac equation but essential for the compatibility (consistency) of the two-body equations. The connections between what are designated as the vertex invariants and the mass and energy potentials are Comparing Eq.(16) with the first equation of this article one finds that the spin-dependent vector interactions are Note that the first portion of the vector potentials is timelike (parallel to while the next portion is spacelike (perpendicular to . The spin-dependent scalar potentials are

The parametrization for and takes advantage of the Todorov effective external potential forms (as seen in the above section on the two-body Klein Gordon equations) and at the same time displays the correct static limit form for the Pauli reduction to Schrödinger-like form. The choice for these parameterizations (as with the two-body Klein Gordon equations) is closely tied to classical or quantum field theories for separate scalar and vector interactions. This amounts to working in the Feynman gauge with the simplest relation between space- and timelike parts of the vector interaction. The mass and energy potentials are respectively so that

Applications and limitations

The TBDE can be readily applied to two body systems such as positronium, muonium, hydrogen-like atoms, quarkonium, and the two-nucleon system.[32][33][34] These applications involve two particles only and do not involve creation or annihilation of particles beyond the two. They involve only elastic processes. Because of the connection between the potentials used in the TBDE and the corresponding quantum field theory, any radiative correction to the lowest order interaction can be incorporated into those potentials. To see how this comes about, consider by contrast how one computes scattering amplitudes without quantum field theory. With no quantum field theory one must come upon potentials by classical arguments or phenomenological considerations. Once one has the potential between two particles, then one can compute the scattering amplitude from the Lippmann–Schwinger equation [35] in which is a Green function determined from the Schrödinger equation. Because of the similarity between the Schrödinger equation Eq. (11) and the relativistic constraint equation (10), one can derive the same type of equation as the above called the quasipotential equation with a very similar to that given in the Lippmann–Schwinger equation. The difference is that with the quasipotential equation, one starts with the scattering amplitudes of quantum field theory, as determined from Feynman diagrams and deduces the quasipotential Φ perturbatively. Then one can use that Φ in (10), to compute energy levels of two particle systems that are implied by the field theory. Constraint dynamics provides one of many, in fact an infinite number of, different types of quasipotential equations (three-dimensional truncations of the Bethe–Salpeter equation) differing from one another by the choice of .[36] The relatively simple solution to the problem of relative time and energy from the generalized mass shell constraint for two particles, has no simple extension, such as presented here with the variable, to either two particles in an external field [37] or to 3 or more particles. Sazdjian has presented a recipe for this extension when the particles are confined and cannot split into clusters of a smaller number of particles with no inter-cluster interactions [38] Lusanna has developed an approach, one that does not involve generalized mass shell constraints with no such restrictions, which extends to N bodies with or without fields. It is formulated on spacelike hypersurfaces and when restricted to the family of hyperplanes orthogonal to the total timelike momentum gives rise to a covariant intrinsic 1-time formulation (with no relative time variables) called the "rest-frame instant form" of dynamics,[39][40]

See also

- Breit equation

- 4-vector

- Dirac equation

- Dirac equation in the algebra of physical space

- Dirac operator

- Electromagnetism

- Kinetic momentum

- Many body problem

- Invariant mass

- Particle physics

- Positronium

- Ricci calculus

- Special relativity

- Spin

- Quantum entanglement

- Relativistic quantum mechanics

References

- ↑ Bethe, Hans A.; Edwin E. Salpeter (2008). Quantum mechanics of one- and two-electron atoms (Dover ed.). Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486466675.

- ↑ Nakanishi, Noboru (1969). "A General Survey of the Theory of the Bethe-Salpeter Equation". Progress of Theoretical Physics Supplement (Oxford University Press (OUP)) 43: 1–81. doi:10.1143/ptps.43.1. ISSN 0375-9687. Bibcode: 1969PThPS..43....1N.

- ↑ Sazdjian, H. (1985). "The quantum mechanical transform of the Bethe-Salpeter equation". Physics Letters B (Elsevier BV) 156 (5–6): 381–384. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(85)91630-2. ISSN 0370-2693. Bibcode: 1985PhLB..156..381S.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Jallouli, H; Sazdjian, H (1997). "The Relativistic Two-Body Potentials of Constraint Theory from Summation of Feynman Diagrams". Annals of Physics 253 (2): 376–426. doi:10.1006/aphy.1996.5632. ISSN 0003-4916. Bibcode: 1997AnPhy.253..376J.

- ↑ P.A.M. Dirac, Can. J. Math. 2, 129 (1950)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 P.A.M. Dirac, Lectures on Quantum Mechanics (Yeshiva University, New York, 1964)

- ↑ P. Van Alstine and H.W. Crater, Journal of Mathematical Physics 23, 1697 (1982).

- ↑ Crater, Horace W; Van Alstine, Peter (1983). "Two-body Dirac equations". Annals of Physics 148 (1): 57–94. doi:10.1016/0003-4916(83)90330-5. Bibcode: 1983AnPhy.148...57C.

- ↑ Sazdjian, H. (1986). "Relativistic wave equations for the dynamics of two interacting particles". Physical Review D 33 (11): 3401–3424. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.33.3401. PMID 9956560. Bibcode: 1986PhRvD..33.3401S.

- ↑ Sazdjian, H. (1986). "Relativistic quarkonium dynamics". Physical Review D 33 (11): 3425–3434. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.33.3425. PMID 9956561. Bibcode: 1986PhRvD..33.3425S.

- ↑ Breit, G. (1929-08-15). "The Effect of Retardation on the Interaction of Two Electrons". Physical Review (American Physical Society (APS)) 34 (4): 553–573. doi:10.1103/physrev.34.553. ISSN 0031-899X. Bibcode: 1929PhRv...34..553B.

- ↑ Breit, G. (1930-08-01). "The Fine Structure of HE as a Test of the Spin Interactions of Two Electrons". Physical Review (American Physical Society (APS)) 36 (3): 383–397. doi:10.1103/physrev.36.383. ISSN 0031-899X. Bibcode: 1930PhRv...36..383B.

- ↑ Breit, G. (1932-02-15). "Dirac's Equation and the Spin-Spin Interactions of Two Electrons". Physical Review (American Physical Society (APS)) 39 (4): 616–624. doi:10.1103/physrev.39.616. ISSN 0031-899X. Bibcode: 1932PhRv...39..616B.

- ↑ Van Alstine, Peter; Crater, Horace W. (1997). "A tale of three equations: Breit, Eddington—Gaunt, and Two-Body Dirac". Foundations of Physics 27 (1): 67–79. doi:10.1007/bf02550156. ISSN 0015-9018. Bibcode: 1997FoPh...27...67A.

- ↑ Crater, Horace W.; Wong, Chun Wa; Wong, Cheuk-Yin (1996). "Singularity-Free Breit Equation from Constraint Two-Body Dirac Equations". International Journal of Modern Physics E 05 (4): 589–615. doi:10.1142/s0218301396000323. ISSN 0218-3013. Bibcode: 1996IJMPE...5..589C.

- ↑ Crater, Horace W.; Peter Van Alstine (1999). "Two-Body Dirac Equations for Relativistic Bound States of Quantum Field Theory". arXiv:hep-ph/9912386.

- ↑ Bergmann, Peter G. (1949-02-15). "Non-Linear Field Theories". Physical Review (American Physical Society (APS)) 75 (4): 680–685. doi:10.1103/physrev.75.680. ISSN 0031-899X. Bibcode: 1949PhRv...75..680B.

- ↑ I. T. Todorov, " Dynamics of Relativistic Point Particles as a Problem with Constraints", Dubna Joint Institute for Nuclear Research No. E2-10175, 1976

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 I. T. Todorov, Annals of the Institute of H. Poincaré' {A28},207 (1978)

- ↑ M. Kalb and P. Van Alstine, Yale Reports, C00-3075-146 (1976), C00-3075-156 (1976),

- ↑ P. Van Alstine, Ph.D. Dissertation Yale University, (1976)

- ↑ Komar, Arthur (1978-09-15). "Constraint formalism of classical mechanics". Physical Review D (American Physical Society (APS)) 18 (6): 1881–1886. doi:10.1103/physrevd.18.1881. ISSN 0556-2821. Bibcode: 1978PhRvD..18.1881K.

- ↑ Komar, Arthur (1978-09-15). "Interacting relativistic particles". Physical Review D (American Physical Society (APS)) 18 (6): 1887–1893. doi:10.1103/physrevd.18.1887. ISSN 0556-2821. Bibcode: 1978PhRvD..18.1887K.

- ↑ Droz-Vincent, Philippe (1975). "Hamiltonian systems of relativistic particles". Reports on Mathematical Physics (Elsevier BV) 8 (1): 79–101. doi:10.1016/0034-4877(75)90020-8. ISSN 0034-4877. Bibcode: 1975RpMP....8...79D.

- ↑ Currie, D. G.; Jordan, T. F.; Sudarshan, E. C. G. (1963-04-01). "Relativistic Invariance and Hamiltonian Theories of Interacting Particles". Reviews of Modern Physics (American Physical Society (APS)) 35 (2): 350–375. doi:10.1103/revmodphys.35.350. ISSN 0034-6861. Bibcode: 1963RvMP...35..350C.

- ↑ Currie, D. G.; Jordan, T. F.; Sudarshan, E. C. G. (1963-10-01). "Erratum: Relativistic Invariance and Hamiltonian Theories of Interacting Particles". Reviews of Modern Physics (American Physical Society (APS)) 35 (4): 1032. doi:10.1103/revmodphys.35.1032.2. ISSN 0034-6861. Bibcode: 1963RvMP...35.1032C.

- ↑ Wong, Cheuk-Yin; Crater, Horace W. (2001-03-23). "RelativisticN-body problem in a separable two-body basis". Physical Review C (American Physical Society (APS)) 63 (4): 044907. doi:10.1103/physrevc.63.044907. ISSN 0556-2813. Bibcode: 2001PhRvC..63d4907W.

- ↑ Horwitz, L. P.; Rohrlich, F. (1985-02-15). "Limitations of constraint dynamics". Physical Review D (American Physical Society (APS)) 31 (4): 932–933. doi:10.1103/physrevd.31.932. ISSN 0556-2821. PMID 9955776. Bibcode: 1985PhRvD..31..932H.

- ↑ Crater, Horace W.; Van Alstine, Peter (1992-07-15). "Restrictions imposed on relativistic two-body interactions by classical relativistic field theory". Physical Review D (American Physical Society (APS)) 46 (2): 766–776. doi:10.1103/physrevd.46.766. ISSN 0556-2821. PMID 10014987. Bibcode: 1992PhRvD..46..766C.

- ↑ Crater, Horace; Yang, Dujiu (1991). "A covariant extrapolation of the noncovariant two particle Wheeler–Feynman Hamiltonian from the Todorov equation and Dirac's constraint mechanics". Journal of Mathematical Physics (AIP Publishing) 32 (9): 2374–2394. doi:10.1063/1.529164. ISSN 0022-2488. Bibcode: 1991JMP....32.2374C.

- ↑ Crater, H. W.; Van Alstine, P. (1990). "Extension of two‐body Dirac equations to general covariant interactions through a hyperbolic transformation". Journal of Mathematical Physics (AIP Publishing) 31 (8): 1998–2014. doi:10.1063/1.528649. ISSN 0022-2488. Bibcode: 1990JMP....31.1998C.

- ↑ Crater, H. W.; Becker, R. L.; Wong, C. Y.; Van Alstine, P. (1992-12-01). "Nonperturbative solution of two-body Dirac equations for quantum electrodynamics and related field theories". Physical Review D (American Physical Society (APS)) 46 (11): 5117–5155. doi:10.1103/physrevd.46.5117. ISSN 0556-2821. PMID 10014894. Bibcode: 1992PhRvD..46.5117C.

- ↑ Crater, Horace; Schiermeyer, James (2010). "Applications of two-body Dirac equations to the meson spectrum with three versus two covariant interactions, SU(3) mixing, and comparison to a quasipotential approach". Physical Review D 82 (9): 094020. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.82.094020. Bibcode: 2010PhRvD..82i4020C.

- ↑ Liu, Bin; Crater, Horace (2003-02-18). "Two-body Dirac equations for nucleon-nucleon scattering". Physical Review C (American Physical Society (APS)) 67 (2): 024001. doi:10.1103/physrevc.67.024001. ISSN 0556-2813. Bibcode: 2003PhRvC..67b4001L.

- ↑ J. J. Sakurai, Modern Quantum Mechanics, Addison Wesley (2010)

- ↑ Yaes, Robert J. (1971-06-15). "Infinite Set of Quasipotential Equations from the Kadyshevsky Equation". Physical Review D (American Physical Society (APS)) 3 (12): 3086–3090. doi:10.1103/physrevd.3.3086. ISSN 0556-2821. Bibcode: 1971PhRvD...3.3086Y.

- ↑ Bijebier, J.; Broekaert, J. (1992). "The two-body plus potential problem between quantum field theory and relativistic quantum mechanics (two-fermion and fermion-boson cases)". Il Nuovo Cimento A (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) 105 (5): 625–640. doi:10.1007/bf02730768. ISSN 0369-3546. Bibcode: 1992NCimA.105..625B.

- ↑ Sazdjian, H (1989). "N-body bound state relativistic wave equations". Annals of Physics (Elsevier BV) 191 (1): 52–77. doi:10.1016/0003-4916(89)90336-9. ISSN 0003-4916. Bibcode: 1989AnPhy.191...52S.

- ↑ Lusanna, Luca (1997-02-10). "The N- and 1-Time Classical Descriptions of N-Body Relativistic Kinematics and the Electromagnetic Interaction". International Journal of Modern Physics A 12 (4): 645–722. doi:10.1142/s0217751x9700058x. ISSN 0217-751X. Bibcode: 1997IJMPA..12..645L.

- ↑ Lusanna, Luca (2013). "From Clock Synchronization to Dark Matter as a Relativistic Inertial Effect". Springer Proceedings in Physics. 144. Heidelberg: Springer International Publishing. pp. 267–343. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-00215-6_8. ISBN 978-3-319-00214-9.

- Childers, R. (1982). "Two-body Dirac equation for semirelativistic quarks". Physical Review D 26 (10): 2902–2915. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.26.2902. Bibcode: 1982PhRvD..26.2902C.

- Childers, R. (1985). "Erratum: Two-body Dirac equation for semirelativistic quarks". Physical Review D 32 (12): 3337. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.32.3337. PMID 9956143. Bibcode: 1985PhRvD..32.3337C.

- Ferreira, P. (1988). "Two-body Dirac equation with a scalar linear potential". Physical Review D 38 (8): 2648–2650. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.38.2648. PMID 9959432. Bibcode: 1988PhRvD..38.2648F.

- Scott, T.; Shertzer, J.; Moore, R. (1992). "Accurate finite-element solutions of the two-body Dirac equation". Physical Review A 45 (7): 4393–4398. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.45.4393. PMID 9907514. Bibcode: 1992PhRvA..45.4393S.

- Patterson, Chris W. (2019). "Anomalous states of Positronium". Physical Review A 100 (6): 062128. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.100.062128. Bibcode: 2019PhRvA.100f2128P.

- Patterson, Chris W. (2023). "Properties of the anomalous states of Positronium". Physical Review A 107 (4): 042816. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.107.042816.

- Various forms of radial equations for the Dirac two-body problem W. Królikowski (1991), Institute of theoretical physics (Warsaw, Poland)

- Duviryak, Askold (2008). "Solvable Two-Body Dirac Equation as a Potential Model of Light Mesons". Symmetry, Integrability and Geometry: Methods and Applications 4: 048. doi:10.3842/SIGMA.2008.048. Bibcode: 2008SIGMA...4..048D.

|