Social:Effects of meditation

The psychological and physiological effects of meditation have been studied. In recent years, studies of meditation have increasingly involved the use of modern instruments, such as fMRI and EEG, which are able to observe brain physiology and neural activity in living subjects, either during the act of meditation itself or before and after meditation. Correlations can thus be established between meditative practices and brain structure or function.[1]

Since the 1950s hundreds of studies on meditation have been conducted, but many of the early studies were flawed and thus yielded unreliable results.[2][3] Contemporary studies have attempted to address many of these flaws with the hope of guiding current research into a more fruitful path.[4] In 2013, researchers found moderate evidence that meditation can reduce anxiety, depression, and pain, but no evidence that it is more effective than active treatments such as drugs or exercise.[5] Another major review article also cautioned about possible misinformation and misinterpretation of data related to the subject.[6][7]

Effects of mindfulness meditation

A previous study commissioned by the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality found that meditation interventions reduce multiple negative dimensions of psychological stress.[5] Other systematic reviews and meta-analyses show that mindfulness meditation has several mental health benefits such as bringing about reductions in depression symptoms,[8][9][10] improvements in mood,[11] stress-resilience[11] and attentional control.[11] Mindfulness interventions also appear to be a promising intervention for managing depression in youth.[12][13] Mindfulness meditation is useful for managing stress,[9][14][15][11] anxiety[8][9][15] and also appears to be effective in treating substance use disorders.[16][17][18] A recent meta analysis by Hilton et al. (2016) including 30 randomized controlled trials found high quality evidence for improvement in depressive symptoms.[19] Other review studies have shown that mindfulness meditation can enhance the psychological functioning of breast cancer survivors,[9] is effective for people with eating disorders[20][21] and may also be effective in treating psychosis.[22][23][24]

Studies have also shown that rumination and worry contribute to mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety,[25] and mindfulness-based interventions are effective in the reduction of worry.[25][26]

Some studies suggest that mindfulness meditation contributes to a more coherent and healthy sense of self and identity, when considering aspects such as sense of responsibility, authenticity, compassion, self-acceptance and character.[27][28]

Brain mechanisms

The analgesic effect of mindfulness meditation may involve multiple brain mechanisms, but there are too few studies to allow conclusions about its effects on chronic pain.[29]

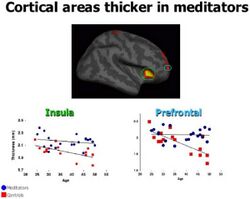

Changes in the brain

Mindfulness meditation is under study for whether structural changes in the brain may occur, but most studies have weak methodology.[30] A meta-analysis found preliminary evidence for effects in the prefrontal cortex and other brain regions associated with body awareness.[31] However, the results should be interpreted with caution because funnel plots indicate that publication bias is an issue in meditation research.[30] A 2016 review using 78 functional neuroimaging studies suggests that different meditation styles are associated with different brain activity.[32]

Attention and mindfulness

Attention networks and mindfulness meditation

Psychological and Buddhist conceptualizations of mindfulness both highlight awareness and attention training as key components, in which levels of mindfulness can be cultivated with practise of mindfulness meditation.[33][11] Focused attention meditation (FAM) and open monitoring meditation (OMM) are distinct types of mindfulness meditation; FAM refers to the practice of intently maintaining focus on one object, whereas OMM is the progression of general awareness of one's surroundings while regulating thoughts.[34][35]

Focused attention meditation is typically practiced first to increase the ability to enhance attentional stability, and awareness of mental states with the goal being to transition to open monitoring meditation practise that emphasizes the ability to monitor moment-by-moment changes in experience, without a focus of attention to maintain. Mindfulness meditation may lead to greater cognitive flexibility.[36]

In an active randomized controlled study completed in 2019, participants who practiced mindfulness meditation demonstrated a greater improvement in awareness and attention than participants in the active control condition.[11] Alpha wave neural oscillation power (which is normally associated with an alert resting state) has been shown to be increased by mindfulness in both healthy subjects and patients.[37]

Sustained attention

Tasks of sustained attention relate to vigilance and the preparedness that aids completing a particular task goal. Psychological research into the relationship between mindfulness meditation and the sustained attention network have revealed the following:

- In a continuous performance task[38] an association was found between higher dispositional mindfulness and more stable maintenance of sustained attention.

- In an EEG study, the attentional blink effect was reduced, and P3b ERP amplitude decreased in a group of participants who completed a mindfulness retreat.[39] The incidence of reduced attentional blink effect relates to an increase in detectability of a second target.

- A greater degree of attentional resources may also be reflected in faster response times in task performance, as was found for participants with higher levels of mindfulness experience.[40]

Selective attention

- Selective attention as linked with the orientation network, is involved in selecting the relevant stimuli to attend to.

- Performance in the ability to limit attention to potentially sensory inputs (i.e. selective attention) was found to be higher following the completion of an eight-week MBSR course, compared to a one-month retreat and control group (with no mindfulness training).[40] The ANT task is a general applicable task designed to test the three attention networks, in which participants are required to determine the direction of a central arrow on a computer screen.[41] Efficiency in orienting that represent the capacity to selectively attend to stimuli was calculated by examining changes in the reaction time that accompanied cues indicating where the target occurred relative to the aid of no cues.

- Meditation experience was found to correlate negatively with reaction times on an Eriksen flanker task measuring responses to global and local figures. Similar findings have been observed for correlations between mindfulness experience in an orienting score of response times taken from Attention Network Task performance.[42]

- Participants who engaged in the Meditation Breath Attention Score exercise performed better on anagram tasks and reported greater focused attention on this task compared to those who did not undergo this exercise.[43]

Executive control attention

- Executive control attention include functions of inhibiting the conscious processing of distracting information. In the context of mindful meditation, distracting information relates to attention grabbing mental events such as thoughts related to the future or past.[35]

- More than one study have reported findings of a reduced Stroop effect following mindfulness meditation training.[36][44][45] The Stroop effect indexes interference created by having words printed in colour that differ to the read semantic meaning e.g. green printed in red. However findings for this task are not consistently found.[46][47] For instance the MBSR may differ to how mindful one becomes relative to a person who is already high in trait mindfulness.[48]

- Using the Attention Network Task (a version of Eriksen flanker task[41]) it was found that error scores that indicate executive control performance were reduced in experienced meditators [40] and following a brief five-session mindfulness training program.[44]

- A neuroimaging study supports behavioural research findings that higher levels of mindfulness are associated with greater proficiency to inhibit distracting information. As greater activation of the rostral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) was shown for mindfulness meditators than matched controls.[49]

- Participants with at least 6 years of experience meditating performed better on the Stroop Test compared to participants who had not had experience meditating.[50] The group of meditators also had lower reaction times during this test than the group of non-meditators.[50]

- Following a Stroop test, reduced amplitude of the P3 ERP component was found for a meditation group relative to control participants. This was taken to signify that mindfulness meditation improves executive control functions of attention. An increased amplitude in the N2 ERP component was also observed in the mindfulness meditation group, thought to reflect more efficient perceptual discrimination in earlier stages of perceptual processing.[51]

Emotion regulation and mindfulness

Research shows meditation practices lead to greater emotional regulation abilities. Mindfulness can help people become more aware of thoughts in the present moment, and this increased self-awareness leads to better processing and control over one's responses to surroundings or circumstances.[52][53]

Positive effects of this heightened awareness include a greater sense of empathy for others, an increase in positive patterns of thinking, and a reduction in anxiety.[53][52] Reductions in rumination also have been found following mindfulness meditation practice, contributing to the development of positive thinking and emotional well-being.[54]

Evidence of mindfulness and emotion regulation outcomes

Emotional reactivity can be measured and reflected in brain regions related to the production of emotions.[55] It can also be reflected in tests of attentional performance, indexed in poorer performance in attention related tasks. The regulation of emotional reactivity as initiated by attentional control capacities can be taxing to performance, as attentional resources are limited.[56]

- Patients with social anxiety disorder (SAD) exhibited reduced amygdala activation in response to negative self-beliefs following an MBSR intervention program that involves mindfulness meditation practice.[57]

- The LPP ERP component indexes arousal and is larger in amplitude for emotionally salient stimuli relative to neutral.[58][59][60] Individuals higher in trait mindfulness showed lower LPP responses to high arousal unpleasant images. These findings suggest that individuals with higher trait mindfulness were better able to regulate emotional reactivity to emotionally evocative stimuli.[61]

- Participants who completed a seven-week mindfulness training program demonstrated a reduction in a measure of emotional interference (measured as slower responses times following the presentation of emotional relative to neutral pictures). This suggests a reduction in emotional interference.[62]

- Following a MBSR intervention, decreases in social anxiety symptom severity were found, as well as increases in bilateral parietal cortex neural correlates. This is thought to reflect the increased employment of inhibitory attentional control capacities to regulate emotions.[63][64]

- Participants who engaged in emotion-focus meditation and breathing meditation exhibited delayed emotional response to negatively valanced film stimuli compared to participants who did not engage in any type of meditation.[65]

Controversies in mindful emotion regulation

It is debated as to whether top-down executive control regions such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC),[66] are required[64] or not[57] to inhibit reactivity of the amygdala activation related to the production of evoked emotional responses. Arguably an initial increase in activation of executive control regions developed during mindfulness training may lessen with increasing mindfulness expertise.[67]

Stress reduction

Research has shown stress reduction benefits from mindfulness.[68][69][70] A 2019 study tested the effects of meditation on the psychological well-being, work stress, and blood pressure of employees working in the United Kingdom. One group of participants were instructed to meditate once a day using a mindfulness app on their smartphones, while the control group did not engage in meditation. Measurements of well-being, stress, and perceived workplace support were taken for both groups before the intervention and then again after four months. Based on self-report questionnaires, the participants who engaged in meditation showed a significant increase in psychological well-being and perceived workplace support. The meditators also reported a significant decrease in anxiety and stress levels.[70]

Another study conducted to understand association between mindfulness, perceived stress and work engagement indicated that mindfulness was associated with lower perceived stress and higher work engagement.[71]

Other research shows decreased stress levels in people who engage in meditation after shorter periods of time as well. Evidence of significant stress reduction was found after only three weeks of meditation intervention.[11] Brief, daily meditation sessions can alter one's behavioral response to stressors, improving coping mechanisms and decreasing the adverse impact caused by stress.[72][73] A study from 2016 examined anxiety and emotional states of naive meditators before and after a seven-day meditation retreat in Thailand. Results displayed a significant reduction in perceived stress after this traditional Buddhist meditation retreat.[73]

Insomnia and sleep

Chronic insomnia is often associated with anxious hyperarousal and frustration over inability to sleep.[74] Mindfulness has been shown to reduce insomnia and improve sleep quality, although self-reported measures show larger effects than objective measures.[74][75] Furthermore, there are case studies of long-term meditators that sleep two hours less than comparable non-meditators, at around two hours of meditation a day.[76]

Future directions

A large part of mindfulness research is dependent on technology. As new technology continues to be developed, new imaging techniques will become useful in this field. Real-time fMRI might give immediate feedback and guide participants through the programs. It could also be used to more easily train and evaluate mental states during meditation itself.[77]

Effects of other types of meditation

Insight (Vipassana) meditation

Vipassana meditation is a component of Buddhist practice. Phra Taweepong Inwongsakul and Sampath Kumar from the University of Mysore have been studying the effects of this meditation on 120 students by measuring the associated increase of cortical thickness in the brain. The results of this study are inconclusive.[78][79] Vipassana meditation leads to more than just mindfulness, but has been found to reduce stress, increase well-being and self-kindness.[80] These effects were found to be most powerful short-term, but still had a relatively significant impact six months later. In a study conducted by Szekeres and Wertheim (2014), they found stress to be the category that seemed to have the most regression, but the others contained higher prevalence when compared to the participants' original scores that were given before embarking on Vipassana meditation. Overall, according to self-reports, Vipassana can have short and long-term effects on an individual.

EEG studies on Vipassana meditators seemed to indicate significant increase in parieto-occipital gamma rhythms in experienced meditators (35–45 Hz).[81] In another study conducted by NIMHANS on Vipassana meditators, researchers found readings associated with improved cognitive processing after a session of meditation, with distinct and graded difference in the readings between novice meditators and experienced meditators.[82]

An essential component to the Vipassana mediation approach is the focus on awareness, referring to bodily sensations and psychological status. In a study conducted by Zeng et al. (2013), awareness was described as the acknowledgement of consciousness which is monitoring all aspects of the environment.[83] This definition differentiates the concept of awareness from mindfulness. The emphasis on awareness, and the way it assists in monitoring emotion, is unique to this meditative practice.

Kundalini yoga

Kundalini yoga has proved to increase the prevention of cognitive decline and evaluate the response of biomarkers to treatment, thereby shedding light on the underlying mechanisms of the link between Kundalini Yoga and cognitive impairment. For the study, 81 participants aged 55 and older who had subjective memory complaints and met criteria for mild cognitive impairment, indicated by a total score of 0.5 on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale. The results showed that at 12 weeks, both the yoga group showed significant improvements in recall memory and visual memory and showed a significant sustained improvement in memory up to the 24-week follow-up, the yoga group showed significant improvement in verbal fluency and sustained significant improvements in executive functioning at week 24. In addition, the yoga cohort showed significant improvement in depressive symptoms, apathy, and resilience from emotional stress. This research was provided by Helen Lavretsky, M.D. and colleagues.[84] In another study, Kundalini Yoga did not show significant effectiveness in treating obsessive-compulsive disorders compared with Relaxation/Meditation.[85]

Sahaja yoga and mental silence

Sahaja yoga meditation is regarded as a mental silence meditation, and has been shown to correlate with particular brain[86][87] and brain wave[88][89][90] characteristics. One study has led to suggestions that Sahaja meditation involves 'switching off' irrelevant brain networks for the maintenance of focused internalized attention and inhibition of inappropriate information.[91] Sahaja meditators appear to benefit from lower depression[92] and scored above control group for emotional well-being and mental health measures on SF-36 ratings.[93][94][95]

A study comparing practitioners of Sahaja Yoga meditation with a group of non-meditators doing a simple relaxation exercise, measured a drop in skin temperature in the meditators compared to a rise in skin temperature in the non-meditators as they relaxed. The researchers noted that all other meditation studies that have observed skin temperature have recorded increases and none have recorded a decrease in skin temperature. This suggests that Sahaja Yoga meditation, being a mental silence approach, may differ both experientially and physiologically from simple relaxation.[90]

Transcendental Meditation

In a 2006 review, Transcendental Meditation (TM) proved comparable with other kinds of relaxation therapies in reducing anxiety.[85] In another 2006 review, study participants demonstrated a one Hertz reduction in EEG alpha wave frequency relative to controls.[96]

A 2012 meta-analysis published in Psychological Bulletin, which reviewed 163 individual studies, found that Transcendental Meditation performed no better overall than other meditation techniques in improving psychological variables.[97]

A 2013 statement from the American Heart Association said that TM could be considered as a treatment for hypertension, although other interventions such as exercise and device-guided breathing were more effective and better supported by clinical evidence.[98]

A 2014 review found moderate evidence for improvement in anxiety, depression and pain with low evidence for improvement in stress and mental health-related quality of life.[99][100]

TM may reduce blood pressure, according to a 2015 review that compared TM to control groups. A trend over time indicated that practicing TM may lower blood pressure. Such effects are comparable to other lifestyle interventions. Conflicting findings across reviews and a potential risk of bias indicated the necessity of further evidence.[101][102]

Research on unspecified or multiple types of meditation

Brain activity

The medial prefrontal and posterior cingulate cortices have been found to be relatively deactivated during meditation by experienced meditators using concentration, lovingkindness and choiceless awareness meditation.[103] In addition experienced meditators were found to have stronger coupling between the posterior cingulate, dorsal anterior cingulate, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices both when meditating and when not meditating.[104] Over time meditation can actually increase the integrity of both gray and white matter. The added amount of gray matter found in the brain stem after meditation improves communication between the cortex and all other areas within the brain.[105][106] Meditation often stimulates a large network of cortical regions including the frontal and parietal regions, lateral occipital lobe, the insular cortex, thalamic nuclei, basal ganglia, and the cerebellum region in the brain. These parts of the brain are connected with attention and the default network of the brain which is associated to day dreaming.[107]

In addition, both meditation and yoga have been found to have impacts on the brain, specifically the caudate.[109] Strengthening of the caudate has been shown in meditators as well as yogis. The increased connectedness of the caudate has potential to be responsible for the improved well-being that is associated with yoga and meditation.[108]

Changes in the brain

Meditation is under preliminary research to assess possible changes in grey matter concentrations.[30]

Published research suggests that meditation can facilitate neuroplasticity and connectivity in brain regions specifically related to emotion regulation and attention.[110][111]

Attention/Mind wandering

Non-directive forms of meditation where the meditator lets their mind wander freely can actually produce higher levels of activity in the default mode network when compared to a resting state or having the brain in a neutral place.[112][113] These Non directive forms of meditation allows the meditators to have better control over thoughts during everyday activities or when focusing on specific task due to a reduced frustration at the brains mind wandering process.[113] When given a specific task, meditation can allow quicker response to changing environmental stimuli. Meditation can allow the brain to decrease attention to unwanted responses of irrelevant environmental stimuli and a reduces the Stroop effect. Those who meditate have regularly demonstrated more control on what they focus their attention on while maintaining a mindful awareness on what is around them.[114] Experienced meditators have been shown to have an increased ability when it comes to conflict monitoring[11] and find it easier to switch between competing stimuli.[115] Those who practice meditation experience an increase of attentional resources in the brain and steady meditation practice can lead to the reduction of the attentional blink due to a decreased mental exertion when identifying important stimuli.[115]

Perception

Studies have shown that meditation has both short-term and long-term effects on various perceptual faculties. In 1984 a study showed that meditators have a significantly lower detection threshold for light stimuli of short duration.[116] In 2000 a study of the perception of visual illusions by zen masters, novice meditators, and non-meditators showed statistically significant effects found for the Poggendorff Illusion but not for the Müller-Lyer Illusion. The zen masters experienced a statistically significant reduction in initial illusion (measured as error in millimeters) and a lower decrement in illusion for subsequent trials.[117] Tloczynski has described the theory of mechanism behind the changes in perception that accompany mindfulness meditation thus: "A person who meditates consequently perceives objects more as directly experienced stimuli and less as concepts… With the removal or minimization of cognitive stimuli and generally increasing awareness, meditation can therefore influence both the quality (accuracy) and quantity (detection) of perception."[117] Brown points to this as a possible explanation of the phenomenon: "[the higher rate of detection of single light flashes] involves quieting some of the higher mental processes which normally obstruct the perception of subtle events."[118] In other words, the practice may temporarily or permanently alter some of the top-down processing involved in filtering subtle events usually deemed noise by the perceptual filters.[118]

Memory

Meditation enhances memory capacity specifically in the working memory and increases executive functioning by helping participants better understand what is happening moment for moment.[119][120] Those who meditate regularly have demonstrated the ability to better process and distinguish important information from the working memory and store it into long-term memory with more accuracy than those who do not practice meditation techniques.[106] Meditation may be able to expand the amount of information that can be held within working memory and by so doing is able to improve IQ scores and increase individual intelligence.[112] The encoding process for both audio and visual information has been shown to be more accurate and detailed when meditation is used.[115] Though there are limited studies on meditation's effects on long-term memory, because of meditations ability to increase attentional awareness, episodic long-term memory is believed to be more vivid and accurate for those who meditate regularly. Meditation has also shown to decrease memory complaints from those with Alzheimer's disease which also suggests the benefits meditation could have on episodic long-term memory which is linked to Alzheimer's.[121]

Calming and relaxation

According to an article in Psychological Bulletin, EEG activity slows as a result of meditation.[122] Some types of meditation may lead to a calming effect by reducing sympathetic nervous system activity while increasing parasympathetic nervous system activity. Or, equivalently, that meditation produces a reduction in arousal and increase in relaxation.[123]

Herbert Benson, founder of the Mind-Body Medical Institute, which is affiliated with Harvard University and several Boston hospitals, reports that meditation induces a host of biochemical and physical changes in the body collectively referred to as the "relaxation response".[124] The relaxation response includes changes in metabolism, heart rate, respiration, blood pressure and brain chemistry. Benson and his team have also done clinical studies at Buddhist monasteries in the Himalaya n Mountains.[125] Benson wrote The Relaxation Response to document the benefits of meditation, which in 1975 were not yet widely known.[126]

Aging

There is no good evidence to indicate that meditation affects the brain in aging.[127]

Happiness and emotional well-being

Studies have shown meditators to have higher happiness than control groups, although this may be due to non-specific factors such as meditators having better general self-care.[128][129][93][92]

Positive relationships have been found between the volume of gray matter in the right precuneus area of the brain and both meditation and the subject's subjective happiness score.[130][131][132][133][30][134] A recent study found that participants who engaged in a body-scan meditation for about 20 minutes self-reported higher levels of happiness and decrease in anxiety compared to participants who just rested during the 20-minute time span. These results suggest that an increase in awareness of one's body through meditation causes a state of selflessness and a feeling of connectedness. This result then leads to reports of positive emotions.[135]

A technique known as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) displays significant benefits for mental health and coping behaviors. Participants who had no prior experience with MBSR reported a significant increase in happiness after eight weeks of MBSR practice. Focus on the present moment and increased awareness of one's thoughts can help monitor and reduce judgment or negative thoughts, causing a report of higher emotional well-being.[136] The MBSR program and evidence for its effectiveness is described in Jon Kabat-Zinn's book Full Catastrophe Living.[137]

Pain

Meditation has been shown to reduce pain perception.[138] An intervention known as mindfulness-based pain management (MBPM) has been subject to a range of studies demonstrating its effectiveness.[139][140]

Potential adverse effects and limits of meditation

The understanding of the potential for adverse effects in meditation is evolving. In 2014, the US government-run National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health suggested that:

Meditation is considered to be safe for healthy people. There have been rare reports that meditation could cause or worsen symptoms in people who have certain psychiatric problems, but this question has not been fully researched.[141]

A 2022 update of the same webpage is more cautionary:

A 2020 review examined 83 studies (a total of 6,703 participants) and found that 55 of those studies reported negative experiences related to meditation practices. The researchers concluded that about 8 percent of participants had a negative effect from practicing meditation, which is similar to the percentage reported for psychological therapies.[142]

Another 2021 review found negative impacts in 37% of the sampled participants in mindfulness-based programmes, with lasting bad effects in 6–14% of the sample, associated with hyperarousal and dissociation.[143]

More broadly, the potential for adverse effects from meditation is well-documented both in scientific articles and the popular press.[144][145][146] Cases of suicide, self-harm, and significant disturbance among meditation practitioners are also documented in canonical and other historical sources.[147][148][149] Organisations such as Cheetah House and Meditating in Safety document research on problems arising in meditation, and offer help for meditators in distress or those recovering from meditation-related health problems. In some cases, adverse effects may be attributed to "improper use of meditation"[150] or the aggravation of a preexisting condition; however, developing research in this area suggests the need for deeper engagement with the causes of severe distress, which previous "meditation teachers have perhaps too quickly and rather insensitively dismissed as pre-existing or unrelated psychopathology".[151] Where meditation is prescribed or offered as a treatment,

Principles of informed consent require that treatment choice be based in part on the balance of benefits to harms, and therefore can only be made if harms are adequately measured and known.[143]

Meditation is not helpful if it used to avoid facing ongoing problems or emerging crises in the meditator's life. In such situations, it may instead be helpful to apply mindful attitudes while actively engaging with current problems.[152][153] According to the NIH, meditation should not be used as a replacement for conventional health care or as a reason to postpone seeing a doctor.[142]

Difficulties in the scientific study of meditation

Weaknesses in historic meditation and mindfulness research

In June 2007, the United States National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) published an independent, peer-reviewed, meta-analysis of the state of meditation research, conducted by researchers at the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center. The report reviewed 813 studies involving five broad categories of meditation: mantra meditation, mindfulness meditation, yoga, tai chi, and qigong, and included all studies on adults through September 2005, with a particular focus on research pertaining to hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and substance abuse. The report concluded:

Scientific research on meditation practices does not appear to have a common theoretical perspective and is characterized by poor methodological quality. Future research on meditation practices must be more rigorous in the design and execution of studies and in the analysis and reporting of results. (p. 6)

It noted that there is no theoretical explanation of health effects from meditation common to all meditation techniques.[2]

A version of this report subsequently published in the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine in 2008 stated: "Most clinical trials on meditation practices are generally characterized by poor methodological quality with significant threats to validity in every major quality domain assessed." This was despite a statistically significant increase in quality of all reviewed meditation research, in general, over time between 1956 and 2005. Of the 400 clinical studies, 10% were found to be good quality. A call was made for rigorous study of meditation.[4] These authors also noted that this finding is not unique to the area of meditation research and that the quality of reporting is a frequent problem in other areas of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) research and related therapy research domains.

Of more than 3,000 scientific studies that were found in a comprehensive search of 17 relevant databases, only about 4% had randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which are designed to exclude the placebo effect.[2]

In a 2013 meta-analysis, Awasthi argued that meditation is defined poorly and despite the research studies showing clinical efficacy, exact mechanisms of action remain unclear.[154] A 2017 commentary was similarly mixed,[6][7] with concerns including the particular characteristics of individuals who tend to participate in mindfulness and meditation research.[155]

Position statements

A 2013 statement from the American Heart Association (AHA) evaluated the evidence for the effectiveness of TM as a treatment for hypertension as "unknown/unclear/uncertain or not well-established", and stated: "Because of many negative studies or mixed results and a paucity of available trials... other meditation techniques are not recommended in clinical practice to lower BP at this time."[156] According to the AHA, while there are promising results about the impact of meditation in reducing blood pressure and managing insomnia, depression and anxiety, it is not a replacement for healthy lifestyle changes and is not a substitute for effective medication.[157]

Methodological obstacles

The term meditation encompasses a wide range of practices and interventions rooted in different traditions, but research literature has sometimes failed to adequately specify the nature of the particular meditation practice(s) being studied.[158] Different forms of meditation practice may yield different results depending on the factors being studied.[158]

The presence of a number of intertwined factors including the effects of meditation, the theoretical orientation of how meditation practices are taught, the cultural background of meditators, and generic group effects complicates the task of isolating the effects of meditation:[68]

Numerous studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of a variety of meditation practices. It has been unclear to what extent these practices share neural correlates. Interestingly, a recent study compared electroencephalogram activity during a focused-attention and open monitoring meditation practice from practitioners of two Buddhist traditions. The researchers found that the differences between the two meditation traditions were more pronounced than the differences between the two types of meditation. These data are consistent with our findings that theoretical orientation of how a practice is taught strongly influences neural activity during these practices. However, the study used long-term practitioners from different cultures, which may have confounded the results.[159]

See also

References

- ↑ Rahimian, Sepehrdad (2021-08-30). "Commentary: Content-Free Awareness: EEG-fcMRI Correlates of Consciousness as Such in an Expert Meditator". PsyArXiv. doi:10.31234/osf.io/6q5b2. https://osf.io/6q5b2.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Meditation practices for health: state of the research". Evidence Report/Technology Assessment (155): 1–263. June 2007. PMID 17764203. PMC 4780968. http://www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/meditation/medit.pdf.

- ↑ Lutz, Antoine; Dunne, John D.; Davidson, Richard J. (2007). "Meditation and the Neuroscience of Consciousness: An Introduction". in Zelazo, Philip David; Moscovitch, Morris; Thompson, Evan. The Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness. Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 499–552. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511816789.020. ISBN 978-0-511-81678-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Clinical trials of meditation practices in health care: characteristics and quality". Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 14 (10): 1199–213. December 2008. doi:10.1089/acm.2008.0307. PMID 19123875.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA Internal Medicine 174 (3): 357–68. March 2014. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018. PMID 24395196.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Mind the Hype: A Critical Evaluation and Prescriptive Agenda for Research on Mindfulness and Meditation". Perspectives on Psychological Science 13 (1): 36–61. January 2018. doi:10.1177/1745691617709589. PMID 29016274.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Stetka, Bret (October 2017). "Where's the Proof That Mindfulness Meditation Works?". Scientific American 29 (1). doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind0118-20. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/wheres-the-proof-that-mindfulness-meditation-works1/.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Mindfulness-based interventions for people diagnosed with a current episode of an anxiety or depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". PLOS ONE 9 (4): e96110. Apr 2014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096110. PMID 24763812. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...996110S.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 "Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis". Journal of Psychosomatic Research 78 (6): 519–28. June 2015. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009. PMID 25818837.

- ↑ "Critical analysis of the efficacy of meditation therapies for acute and subacute phase treatment of depressive disorders: a systematic review". Psychosomatics 56 (2): 140–52. 2014. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2014.10.007. PMID 25591492. PMC 4383597. http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/0372c9xp.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Walsh, Kathleen Marie; Saab, Bechara J; Farb, Norman AS (2019-01-08). "Effects of a Mindfulness Meditation App on Subjective Well-Being: Active Randomized Controlled Trial and Experience Sampling Study" (in en). JMIR Mental Health 6 (1): e10844. doi:10.2196/10844. ISSN 2368-7959. PMID 30622094.

- ↑ "Meditation and mindfulness in clinical practice". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 23 (3): 487–534. July 2014. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2014.03.002. PMID 24975623.

- ↑ "Mindfulness Interventions with Youth: A Meta-Analysis". Mindfulness 59 (4): 297–302. Jan 2014. doi:10.1093/sw/swu030. PMID 25365830.

- ↑ "Mindfulness-based stress reduction as a stress management intervention for healthy individuals: a systematic review". Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine 19 (4): 271–86. October 2014. doi:10.1177/2156587214543143. PMID 25053754.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 78 (2): 169–83. April 2010. doi:10.1037/a0018555. PMID 20350028.

- ↑ "Are mindfulness-based interventions effective for substance use disorders? A systematic review of the evidence". Substance Use & Misuse 49 (5): 492–512. April 2014. doi:10.3109/10826084.2013.770027. PMID 23461667.

- ↑ "Mindfulness training targets neurocognitive mechanisms of addiction at the attention-appraisal-emotion interface". Frontiers in Psychiatry 4 (173): 173. January 2014. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00173. PMID 24454293.

- ↑ "Mindfulness-based interventions: an antidote to suffering in the context of substance use, misuse, and addiction". Substance Use & Misuse 49 (5): 487–91. April 2014. doi:10.3109/10826084.2014.860749. PMID 24611846.

- ↑ "Mindfulness Meditation for Chronic Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Annals of Behavioral Medicine 51 (2): 199–213. April 2017. doi:10.1007/s12160-016-9844-2. PMID 27658913.

- ↑ "Mindfulness-based interventions for binge eating: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Behavioral Medicine 38 (2): 348–62. April 2015. doi:10.1007/s10865-014-9610-5. PMID 25417199.

- ↑ "Mindfulness and weight loss: a systematic review". Psychosomatic Medicine 77 (1): 59–67. January 2015. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000127. PMID 25490697.

- ↑ "Do mindfulness-based therapies have a role in the treatment of psychosis?". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 48 (2): 124–7. February 2014. doi:10.1177/0004867413512688. PMID 24220133. http://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/26548/1/PubSub3164_Griffiths.pdf.

- ↑ "Mindfulness for psychosis". The British Journal of Psychiatry 204 (5): 333–4. May 2014. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.113.136044. PMID 24785766.

- ↑ "Mindfulness interventions for psychosis: a meta-analysis". Schizophrenia Research 150 (1): 176–84. October 2013. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.055. PMID 23954146.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Assessing treatments used to reduce rumination and/or worry: a systematic review". Clinical Psychology Review 33 (8): 996–1009. December 2013. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.004. PMID 24036088. http://epubs.surrey.ac.uk/805216/6/Querstret%26Cropley_2013.pdf.

- ↑ "How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of meditation studies". Clinical Psychology Review 37: 1–12. April 2015. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006. PMID 25689576.

- ↑ "Mindfulness meditation and explicit and implicit indicators of personality and self-concept changes". Frontiers in Psychology 6: 44. 2015. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00044. PMID 25688222.

- ↑ "Improving personality/character traits in individuals with alcohol dependence: the influence of mindfulness-oriented meditation". Journal of Addictive Diseases 34 (1): 75–87. 2015. doi:10.1080/10550887.2014.991657. PMID 25585050.

- ↑ "Neuromodulatory treatments for chronic pain: efficacy and mechanisms". Nature Reviews. Neurology 10 (3): 167–78. March 2014. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2014.12. PMID 24535464.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 "Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 43: 48–73. June 2014. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.016. PMID 24705269.

- ↑ Fox, Kieran C. R.; Nijeboer, Savannah; Dixon, Matthew L.; Floman, James L.; Ellamil, Melissa; Rumak, Samuel P.; Sedlmeier, Peter; Christoff, Kalina (June 2014). "Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 43: 48–73. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.016. ISSN 1873-7528. PMID 24705269.

- ↑ "Functional neuroanatomy of meditation: A review and meta-analysis of 78 functional neuroimaging investigations". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 65: 208–28. June 2016. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.03.021. PMID 27032724. Bibcode: 2016arXiv160306342F.

- ↑ "Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future". Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 10 (2): 144–156. 2003. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bpg016.

- ↑ "Focused attention, open monitoring and loving kindness meditation: effects on attention, conflict monitoring, and creativity - A review". Frontiers in Psychology 5: 1083. 2014. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01083. PMID 25295025.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation". Trends in Cognitive Sciences 12 (4): 163–9. April 2008. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.005. PMID 18329323.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "Meditation, mindfulness and cognitive flexibility". Consciousness and Cognition 18 (1): 176–86. March 2009. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2008.12.008. PMID 19181542.

- ↑ "A systematic review of the neurophysiology of mindfulness on EEG oscillations". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 57: 401–410. October 2015. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.09.018. PMID 26441373. http://roar.uel.ac.uk/4509/1/A%20systematic%20review%20of%20the%20neurophysiology%20of.pdf.

- ↑ "The relation between self-report mindfulness and performance on tasks of sustained attention". Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 31 (1): 60–66. 2009. doi:10.1007/s10862-008-9086-0.

- ↑ "Mental training affects distribution of limited brain resources". PLOS Biology 5 (6): e138. June 2007. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050138. PMID 17488185.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 "Mindfulness training modifies subsystems of attention". Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience 7 (2): 109–19. June 2007. doi:10.3758/cabn.7.2.109. PMID 17672382.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 14 (3): 340–7. April 2002. doi:10.1162/089892902317361886. PMID 11970796.

- ↑ "Greater efficiency in attentional processing related to mindfulness meditation". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 63 (6): 1168–80. June 2010. doi:10.1080/17470210903249365. PMID 20509209.

- ↑ Green, Joseph P.; Black, Katharine N. (2017). "Meditation-focused attention with the MBAS and solving anagrams.". Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice 4 (4): 348–366. doi:10.1037/cns0000113. ISSN 2326-5531.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "Short-term meditation training improves attention and self-regulation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (43): 17152–6. October 2007. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707678104. PMID 17940025. Bibcode: 2007PNAS..10417152T.

- ↑ "Effects of level of meditation experience on attentional focus: is the efficiency of executive or orientation networks improved?". Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 13 (6): 651–7. 2007. doi:10.1089/acm.2007.7022. PMID 17718648.

- ↑ "Mindfulness-based stress reduction and attentional control". Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 14 (6): 449–463. 2007. doi:10.1002/cpp.544.

- ↑ "How Does Mindfulness Meditation Work? Proposing Mechanisms of Action From a Conceptual and Neural Perspective". Perspectives on Psychological Science 6 (6): 537–59. November 2011. doi:10.1177/1745691611419671. PMID 26168376. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/73b8a5091dc9a8a7ea60b81641689bb5ccc5aea1.

- ↑ "Neural mechanisms of attentional control in mindfulness meditation". Frontiers in Neuroscience 7: 8. 2013. doi:10.3389/fnins.2013.00008. PMID 23382709.

- ↑ Marchand, William R (2014-07-28). "Neural mechanisms of mindfulness and meditation: Evidence from neuroimaging studies". World Journal of Radiology 6 (7): 471–479. doi:10.4329/wjr.v6.i7.471. ISSN 1949-8470. PMID 25071887.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 "Long-term meditation: the relationship between cognitive processes, thinking styles and mindfulness". Cognitive Processing 19 (1): 73–85. February 2018. doi:10.1007/s10339-017-0844-3. PMID 29110263.

- ↑ "Regular, brief mindfulness meditation practice improves electrophysiological markers of attentional control". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 6: 18. 2012. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2012.00018. PMID 22363278.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Chawla, Neharika; Marlatt, G. Alan (2010). "Mindlessness-Mindfulness". The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. American Cancer Society. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0549. ISBN 9780470479216.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Baer, Ruth A. (2003). "Mindfulness Training as a Clinical Intervention: A Conceptual and Empirical Review". Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 10 (2): 125–143. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bpg015.

- ↑ Wolkin, Jennifer R (2015-06-29). "Cultivating multiple aspects of attention through mindfulness meditation accounts for psychological well-being through decreased rumination". Psychology Research and Behavior Management 8: 171–180. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S31458. ISSN 1179-1578. PMID 26170728.

- ↑ "The cognitive control of emotion". Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9 (5): 242–9. May 2005. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.010. PMID 15866151.

- ↑ "Research on attention networks as a model for the integration of psychological science". Annual Review of Psychology 58: 1–23. 2007. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085516. PMID 17029565.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 "Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder". Emotion 10 (1): 83–91. February 2010. doi:10.1037/a0018441. PMID 20141305.

- ↑ "Brain potentials in affective picture processing: covariation with autonomic arousal and affective report". Biological Psychology 52 (2): 95–111. March 2000. doi:10.1016/s0301-0511(99)00044-7. PMID 10699350. https://kops.uni-konstanz.de/bitstreams/07fb2c65-fed1-4bc9-8c84-50fc2e96641d/download.

- ↑ "Affective picture processing: the late positive potential is modulated by motivational relevance". Psychophysiology 37 (2): 257–61. March 2000. doi:10.1111/1469-8986.3720257. PMID 10731776. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:352-opus-21050.

- ↑ "Attention and emotion: an ERP analysis of facilitated emotional stimulus processing". NeuroReport 14 (8): 1107–10. June 2003. doi:10.1097/00001756-200306110-00002. PMID 12821791.

- ↑ "Dispositional mindfulness and the attenuation of neural responses to emotional stimuli". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 8 (1): 93–9. January 2013. doi:10.1093/scan/nss004. PMID 22253259.

- ↑ "Mindfulness meditation and reduced emotional interference on a cognitive task". Motivation and Emotion 31 (4): 271–283. 2007. doi:10.1007/s11031-007-9076-7.

- ↑ "MBSR vs aerobic exercise in social anxiety: fMRI of emotion regulation of negative self-beliefs". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 8 (1): 65–72. January 2013. doi:10.1093/scan/nss054. PMID 22586252.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 "Attending to the present: mindfulness meditation reveals distinct neural modes of self-reference". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 2 (4): 313–22. December 2007. doi:10.1093/scan/nsm030. PMID 18985137.

- ↑ "Breath Versus Emotions: The Impact of Different Foci of Attention During Mindfulness Meditation on the Experience of Negative and Positive Emotions". Behavior Therapy 49 (5): 702–714. September 2018. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2017.12.006. PMID 30146138.

- ↑ "Prefrontal involvement in the regulation of emotion: convergence of rat and human studies". Current Opinion in Neurobiology 16 (6): 723–7. December 2006. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2006.07.004. PMID 17084617.

- ↑ "Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings". Clinical Psychology Review 31 (3): 449–64. April 2011. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.11.003. PMID 21183265.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 "Common and Dissociable Neural Activity After Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Relaxation Response Programs". Psychosomatic Medicine 80 (5): 439–451. June 2018. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000590. PMID 29642115.

- ↑ "Mindfulness, Meditation, Relaxation Response Have Different Effects on Brain Function". 2018-06-13. https://www.laboratoryequipment.com/news/2018/06/mindfulness-meditation-relaxation-response-have-different-effects-brain-function.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Bostock, Sophie; Crosswell, Alexandra D.; Prather, Aric A.; Steptoe, Andrew (2019). "Mindfulness on-the-go: Effects of a mindfulness meditation app on work stress and well-being." (in en). Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 24 (1): 127–138. doi:10.1037/ocp0000118. ISSN 1939-1307. PMID 29723001.

- ↑ Bartlett, Larissa; Buscot, Marie-Jeanne; Bindoff, Aidan; Chambers, Richard; Hassed, Craig (2021). "Mindfulness Is Associated With Lower Stress and Higher Work Engagement in a Large Sample of MOOC Participants". Frontiers in Psychology 12: 724126. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.724126. ISSN 1664-1078. PMID 34566805.

- ↑ Basso, Julia C.; McHale, Alexandra; Ende, Victoria; Oberlin, Douglas J.; Suzuki, Wendy A. (2019). "Brief, daily meditation enhances attention, memory, mood, and emotional regulation in non-experienced meditators". Behavioural Brain Research 356: 208–220. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2018.08.023. ISSN 0166-4328. PMID 30153464.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Surinrut, Piyawan; Auamnoy, Titinun; Sangwatanaroj, Somkiat (2016). "Enhanced happiness and stress alleviation upon insight meditation retreat: mindfulness, a part of traditional Buddhist meditation". Mental Health, Religion & Culture 19 (7): 648–659. doi:10.1080/13674676.2016.1207618. ISSN 1367-4676.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 "What do we really know about mindfulness and sleep health?". Current Opinion in Psychology 34: 18–22. 2020. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.08.020. PMID 31539830.

- ↑ "The Effect of Mind-Body Therapies on Insomnia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 13: 9359807. 2019. doi:10.1155/2019/9359807. PMID 30894878.

- ↑ Kaul, Prashant; Passafiume, Jason; Sargent, R. Craig; O'Hara, Bruce F. (2010-07-29). "Meditation acutely improves psychomotor vigilance, and may decrease sleep need". Behavioral and Brain Functions 6 (1): 47. doi:10.1186/1744-9081-6-47. ISSN 1744-9081. PMID 20670413.

- ↑ "Tools of the trade: theory and method in mindfulness neuroscience". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 8 (1): 118–20. January 2013. doi:10.1093/scan/nss112. PMID 23081977.

- ↑ Inwongsakul PT (September 2015). Impact of vipassana meditation on life satisfaction and quality of life (PhD thesis). University of Mysore.

- ↑ Dargah M (April 2017). The Impact of Vipassana Meditation on Quality of Life (PhD thesis). The Chicago School of Professional Psychology.

- ↑ Szekeres, Roberta A.; Wertheim, Eleanor H. (December 2015). "Evaluation of Vipassana Meditation Course Effects on Subjective Stress, Well-being, Self-kindness and Mindfulness in a Community Sample: Post-course and 6-month Outcomes: Vipassana , Stress, Mindfulness and Well-being" (in en). Stress and Health 31 (5): 373–381. doi:10.1002/smi.2562. PMID 24515781.

- ↑ Cahn, BR; Delorme, A; Polich, J (February 2010). "Occipital gamma activation during Vipassana meditation.". Cognitive Processing 11 (1): 39–56. doi:10.1007/s10339-009-0352-1. PMID 20013298.

- ↑ Kakumanu, Ratna Jyothi; Nair, Ajay Kumar; Sasidharan, Arun; John, John P.; Mehrotra, Seema; Panth, Ravindra; Kutty, Bindu M. (2019). "State-trait influences of Vipassana meditation practice on P3 EEG dynamics". Meditation. Progress in Brain Research. 244. pp. 115–136. doi:10.1016/bs.pbr.2018.10.027. ISBN 9780444642271.

- ↑ Zeng, Xianglong; Oei, Tian P. S.; Liu, Xiangping (December 2014). "Monitoring Emotion Through Body Sensation: A Review of Awareness in Goenka's Vipassana" (in en). Journal of Religion and Health 53 (6): 1693–1705. doi:10.1007/s10943-013-9754-6. ISSN 0022-4197. PMID 23846450.

- ↑ Watts, Vabren (2016). "Kundalini Yoga Found to Enhance Cognitive Functioning in Older Adults". Psychiatric News 51 (9): 1. doi:10.1176/appi.pn.2016.4b11.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 "Meditation therapy for anxiety disorders". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004998. January 2006. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004998.pub2. PMID 16437509.

- ↑ "Monitoring the neural activity of the state of mental silence while practicing Sahaja yoga meditation". Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 21 (3): 175–9. March 2015. doi:10.1089/acm.2013.0450. PMID 25671603.

- ↑ "Gray Matter and Functional Connectivity in Anterior Cingulate Cortex are Associated with the State of Mental Silence During Sahaja Yoga Meditation". Neuroscience 371: 395–406. February 2018. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.12.017. PMID 29275207.

- ↑ "Human anterior and frontal midline theta and lower alpha reflect emotionally positive state and internalized attention: high-resolution EEG investigation of meditation". Neuroscience Letters 310 (1): 57–60. September 2001. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(01)02094-8. PMID 11524157.

- ↑ "Impact of regular meditation practice on EEG activity at rest and during evoked negative emotions". The International Journal of Neuroscience 115 (6): 893–909. June 2005. doi:10.1080/00207450590897969. PMID 16019582.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Manocha, Ramesh; Black, Deborah; Spiro, David; Ryan, Jake; Stough, Con (March 2010). "Changing Definitions of Meditation – Is there a Physiological Corollary? Skin temperature changes of a mental silence orientated form of meditation compared to rest". Journal of the International Society of Life Sciences 28 (1): 23–31. http://www.researchingmeditation.org/meditation_research/skintemp.pdf. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ↑ "Non-linear dynamic complexity of the human EEG during meditation". Neuroscience Letters 330 (2): 143–6. September 2002. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00745-0. PMID 12231432.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 "The effects of Sahaja Yoga meditation on mental health: a systematic review". Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine 15 (3). May 2018. doi:10.1515/jcim-2016-0163. PMID 29847314.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 "Quality of life and functional health status of long-term meditators". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2012: 1–9. 2012. doi:10.1155/2012/350674. PMID 22611427.

- ↑ Manocha, Ramesh (2014). "Meditation, mindfulness and mind-emptiness". Acta Neuropsychiatrica 23: 46–7. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5215.2010.00519.x.

- ↑ Morgon A. Sahaja Yoga: an Ancient Path to Modern Mental Health? (Doctor of Clinical Psychology thesis). University of Plymouth.

- ↑ "Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies". Psychological Bulletin 132 (2): 180–211. 2006. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.180. PMID 16536641.

- ↑ Sedlmeier, Peter et al. (May 2012). "The Psychological Effects of Meditation: A Meta-Analysis". Psychological Bulletin 138 (6): 1139–1171. doi:10.1037/a0028168. PMID 22582738. "The global analysis yielded quite comparable effects for TM, mindfulness meditation, and the other meditation procedures...So, it seems that the three categories we identified for the sake of comparison, TM, mindfulness meditation, and the heterogeneous category we termed other meditation techniques, do not differ in their overall effects.".

- ↑ "Beyond medications and diet: alternative approaches to lowering blood pressure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association". Hypertension 61 (6): 1360–83. 2013. doi:10.1161/HYP.0b013e318293645f. PMID 23608661.

- ↑ "Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA Intern Med 174 (3): 357–68. 2014. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018. PMID 24395196. "... we found low evidence of no effect or insufficient evidence that mantra meditation programs had an effect on any of the psychological stress and well-being outcomes we examined.".

- ↑ Meditation Programs for Psychological Stress and Well-Being. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2014. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0063263/. "Our review finds that the mantra meditation programs do not appear to improve any of the psychological stress and well-being outcomes we examined, but the strength of this evidence varies from low to insufficient."

- ↑ Bai, Z; Chang, J; Chen, C; Li, P; Yang, K; Chi, I (February 2015). "Investigating the effect of transcendental meditation on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Human Hypertension (Nature Publishing Group) 29 (11): 653–662. doi:10.1038/jhh.2015.6. ISSN 1476-5527. PMID 25673114.

- ↑ Ooi, Soo Liang; Giovino, Melisa; Pak, Sok Chean (October 2017). "Transcendental meditation for lowering blood pressure: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses". Complementary Therapies in Medicine (Elsevier) 34: 26–34. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2017.07.008. ISSN 1873-6963. PMID 28917372.

- ↑ Brewer, J. A.; Worhunsky, P. D.; Gray, J. R.; Tang, Y.-Y.; Weber, J.; Kober, H. (2011-11-23). "Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (50): 20254–20259. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112029108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 22114193. Bibcode: 2011PNAS..10820254B.

- ↑ "Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 (50): 20254–9. December 2011. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112029108. PMID 22114193. Bibcode: 2011PNAS..10820254B.

- ↑ Baer, Ruth (2010-05-01) (in en). Assessing Mindfulness and Acceptance Processes in Clients: Illuminating the Theory and Practice of Change. New Harbinger Publications. ISBN 978-1-60882-263-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=DlnH-qadA08C&q=meditation+and+neuroplasticity&pg=PA185.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 Chambers, Richard; Lo, Barbara Chuen Yee; Allen, Nicholas B. (2008-06-01). "The Impact of Intensive Mindfulness Training on Attentional Control, Cognitive Style, and Affect" (in en). Cognitive Therapy and Research 32 (3): 303–322. doi:10.1007/s10608-007-9119-0. ISSN 1573-2819.

- ↑ Brefczynski-Lewis, J. A.; Lutz, A.; Schaefer, H. S.; Levinson, D. B.; Davidson, R. J. (2007-07-03). "Neural correlates of attentional expertise in long-term meditation practitioners" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104 (27): 11483–11488. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606552104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 17596341. Bibcode: 2007PNAS..10411483B.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 Gard, Tim; Taquet, Maxime; Dixit, Rohan; Hölzel, Britta K.; Dickerson, Bradford C.; Lazar, Sara W. (2015-03-16). "Greater widespread functional connectivity of the caudate in older adults who practice kripalu yoga and vipassana meditation than in controls". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 9: 137. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00137. ISSN 1662-5161. PMID 25852521.

- ↑ Gard, Tim; Taquet, Maxime; Dixit, Rohan; Hölzel, Britta K.; Dickerson, Bradford C.; Lazar, Sara W. (2015). "Greater widespread functional connectivity of the caudate in older adults who practice kripalu yoga and vipassana meditation than in controls" (in English). Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 9: 137. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00137. ISSN 1662-5161. PMID 25852521.

- ↑ Vago, David R.; Silbersweig, David A. (2012). "Self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence (S-ART): a framework for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 6: 296. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2012.00296. PMID 23112770.

- ↑ Hölzel, Britta K.; Lazar, Sara W.; Gard, Tim; Schuman-Olivier, Zev; Vago, David R.; Ott, Ulrich (November 2011). "How Does Mindfulness Meditation Work? Proposing Mechanisms of Action From a Conceptual and Neural Perspective". Perspectives on Psychological Science 6 (6): 537–559. doi:10.1177/1745691611419671. PMID 26168376.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 Mrazek, Michael D.; Franklin, Michael S.; Phillips, Dawa Tarchin; Baird, Benjamin; Schooler, Jonathan W. (2013-03-28). "Mindfulness Training Improves Working Memory Capacity and GRE Performance While Reducing Mind Wandering" (in en-US). Psychological Science 24 (5): 776–781. doi:10.1177/0956797612459659. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 23538911.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 Xu, Jian; Vik, Alexandra; Groote, Inge Rasmus; Lagopoulos, Jim; Holen, Are; Ellingsen, Øyvind; Davanger, Svend (2014). "Nondirective meditation activates default mode network and areas associated with memory retrieval and emotional processing" (in English). Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8: 86. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00086. ISSN 1662-5161. PMID 24616684.

- ↑ Semple, Randye J. (2010-06-01). "Does Mindfulness Meditation Enhance Attention? A Randomized Controlled Trial" (in en). Mindfulness 1 (2): 121–130. doi:10.1007/s12671-010-0017-2. ISSN 1868-8535.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 115.2 Brown, Kirk Warren; Creswell, J. David; Ryan, Richard M. (2015-11-17) (in en). Handbook of Mindfulness: Theory, Research, and Practice. Guilford Publications. ISBN 978-1-4625-2593-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZF-uCgAAQBAJ&q=meditation+and+episodic+memory&pg=PA190.

- ↑ "Differences in visual sensitivity among mindfulness meditators and non-meditators". Perceptual and Motor Skills 58 (3): 727–33. June 1984. doi:10.2466/pms.1984.58.3.727. PMID 6382144.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 "Perception of visual illusions by novice and longer-term meditators". Perceptual and Motor Skills 91 (3 Pt 1): 1021–6. December 2000. doi:10.2466/pms.2000.91.3.1021. PMID 11153836.

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 Brown, Daniel; Forte, Michael; Dysart, Michael (June 1984). "Visual Sensitivity and Mindfulness Meditation". Perceptual and Motor Skills 58 (3): 775–784. doi:10.2466/pms.1984.58.3.775. ISSN 0031-5125. PMID 6382145. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pms.1984.58.3.775.

- ↑ Gallant, Sara N. (2016-02-01). "Mindfulness meditation practice and executive functioning: Breaking down the benefit" (in en). Consciousness and Cognition 40: 116–130. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2016.01.005. ISSN 1053-8100. PMID 26784917. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1053810016300058.

- ↑ Bailey, N. W.; Freedman, G.; Raj, K.; Spierings, K. N.; Piccoli, L. R.; Sullivan, C. M.; Chung, S. W.; Hill, A. T. et al. (2019-10-16). "Mindfulness meditators show enhanced working memory performance concurrent with different brain region engagement patterns during recall" (in en). bioRxiv: 801746. doi:10.1101/801746. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/801746v1.

- ↑ Thompson, Lynn C. (2004). "A Pilot Study of a Yoga and Meditation Intervention for Dementia Caregiver Stress". Journal of Clinical Psychology 60 (6): 677–687. doi:10.1002/jclp.10259. PMID 15141399.

- ↑ "Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies". Psychological Bulletin 132 (2): 180–211. March 2006. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.180. PMID 16536641.

- ↑ Flanagan, Steven R.; Zaretsky, PhD, Dr. Herb; Moroz, MD, Alex (2011). Medical Aspects of Disability, Fourth Edition (Fourth ed.). Springer. p. 596. ISBN 9780826127846. https://books.google.com/books?id=azCbzY2q0_kC. "It is thought that some types of meditation might work by reducing activity in the sympathetic nervous system and increasing activity in the parasympathetic nervous system"

- ↑ "The relaxation response: therapeutic effect". Science 278 (5344): 1694–5. December 1997. doi:10.1126/science.278.5344.1693b. PMID 9411784. Bibcode: 1997Sci...278.1693B.

- ↑ Cromie, William J. (18 April 2002). "Meditation changes temperatures: Mind controls body in extreme experiments". Harvard University Gazette. http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/2002/04.18/09-tummo.html.

- ↑ Benson, Herbert (2001). The Relaxation Response. HarperCollins. pp. 61–3. ISBN 978-0-380-81595-1. https://archive.org/details/relaxationrespon00bens_0/page/61.[non-primary source needed]

- ↑ Luders, Eileen; Cherbuin, Nicolas (2016-05-17). "Searching for the philosopher's stone: promising links between meditation and brain preservation". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1373 (1): 38–44. doi:10.1111/nyas.13082. ISSN 0077-8923. PMID 27187107. Bibcode: 2016NYASA1373...38L.

- ↑ "Efficacy of rajayoga meditation on positive thinking: an index for self-satisfaction and happiness in life". Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 7 (10): 2265–7. October 2013. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2013/5889.3488. PMID 24298493.

- ↑ Campos, Daniel; Cebolla, Ausiàs; Quero, Soledad; Bretón-López, Juana; Botella, Cristina; Soler, Joaquim; García-Campayo, Javier; Demarzo, Marcelo et al. (2016). "Meditation and happiness: Mindfulness and self-compassion may mediate the meditation–happiness relationship". Personality and Individual Differences 93: 80–85. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.040.

- ↑ "The structural neural substrate of subjective happiness". Scientific Reports 5: 16891. November 2015. doi:10.1038/srep16891. PMID 26586449. Bibcode: 2015NatSR...516891S.

- ↑ "Brain Gray Matter Changes Associated with Mindfulness Meditation in Older Adults: An Exploratory Pilot Study using Voxel-based Morphometry". Neuro 1 (1): 23–26. 2014. doi:10.17140/NOJ-1-106. PMID 25632405.

- ↑ "Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density". Psychiatry Research 191 (1): 36–43. January 2011. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006. PMID 21071182.

- ↑ "Shifting brain asymmetry: the link between meditation and structural lateralization". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 10 (1): 55–61. January 2015. doi:10.1093/scan/nsu029. PMID 24643652.

- ↑ "Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 5 (1): 11–7. March 2010. doi:10.1093/scan/nsp034. PMID 19776221.

- ↑ "When the dissolution of perceived body boundaries elicits happiness: The effect of selflessness induced by a body scan meditation". Consciousness and Cognition 46: 89–98. November 2016. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2016.09.013. PMID 27684609.

- ↑ "Mindfulness-based stress reduction and attentional control". Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 14 (6): 449–463. 2007. doi:10.1002/cpp.544.

- ↑ Kabat-Zinn, Jon (2013) (in en). Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness (2nd ed.). Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-345-53972-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=fIuNDtnb2ZkC.

- ↑ "Meditation reduces pain-related neural activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, insula, secondary somatosensory cortex, and thalamus". Frontiers in Psychology 5: 1489. 2014. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01489. PMID 25566158.

- ↑ "A literature review of Breathworks and mindfulness intervention". British Journal of Healthcare Management 24 (5): 235–241. 2018. doi:10.12968/bjhc.2018.24.5.235.

- ↑ "Psychobiological correlates of improved mental health in patients with musculoskeletal pain after a mindfulness-based pain management program". The Clinical Journal of Pain 29 (3): 233–44. March 2013. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31824c5d9f. PMID 22874090.

- ↑ National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (2014). "Meditation: What You Need To Know". http://nccih.nih.gov/health/meditation/overview.htm.

- ↑ 142.0 142.1 "Meditation and Mindfulness: What You Need To Know". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. June 2022. http://nccih.nih.gov/health/meditation/overview.htm.

- ↑ 143.0 143.1 Britton, Willoughby B; Lindahl, Jared R; Cooper, David J; Canby, Nicholas K; Palitsky, Roman (2021). "Defining and measuring meditation-related adverse effects in mindfulness-based programs". Clinical Psychological Science (SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA) 9 (6): 1185–1204. doi:10.1177/2167702621996340. PMID 35174010.

- ↑ Shapiro Jr, Deane H (1992). "Adverse Effects of Meditation: A Preliminary Investigation of Long-Term Meditators". International Journal of Psychosomatics 39 (1–4): 63. PMID 1428622. http://deanehshapirojr.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Adverse-Effect-of-Meditation.pdf.

- ↑ Perez-De-Albeniz, Alberto; Holmes, Jeremy (2000). "Meditation: Concepts, effects and uses in therapy". International Journal of Psychotherapy 5 (1): 49–58. doi:10.1080/13569080050020263.

- ↑ Rocha, Tomas (25 June 2014). "The Dark Knight of the Soul". https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/06/the-dark-knight-of-the-souls/372766/?single_page=true.

- ↑ "Vesali Sutta: At Vesali". https://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn54/sn54.009.than.html.

- ↑ "Cutting Off Your Arm On a Snowy Morning". 2021. https://www.sotozen.com/eng/library/stories/vol02.html.

- ↑ Hakuin (2010). Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin. Shambhala Publications.

- ↑ "Religious or spiritual problem. A culturally sensitive diagnostic category in the DSM-IV". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183 (7): 435–44. July 1995. doi:10.1097/00005053-199507000-00003. PMID 7623015.

- ↑ Lutkajtis, Anna (2019). "Delineating the 'dark night' in Buddhist postmodernism". Literature & Aesthetics 29 (2).

- ↑ Hayes, Steven C.; Strosahl, Kirk D.; Wilson, Kelly G. (1999). "3". Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change. New York: Guilford. ISBN 978-1-57230-481-9.

- ↑ Metzner, Ralph (2005). "Psychedelic, Psychoactive and Addictive Drugs and States of Consciousness". in Earlywine, Mitch. Mind-Altering Drugs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 25–48. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195165319.003.0002. ISBN 978-0-19-516531-9.

- ↑ Awasthi B (2013). "Issues and perspectives in meditation research: in search for a definition". Frontiers in Psychology 3: 613. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00613. PMID 23335908.

- ↑ "Reiterated Concerns and Further Challenges for Mindfulness and Meditation Research: A Reply to Davidson and Dahl". Perspectives on Psychological Science 13 (1): 66–69. January 2018. doi:10.1177/1745691617727529. PMID 29016240.

- ↑ "Beyond Medications and Diet: Alternative Approaches to Lowering Blood Pressure: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association". Hypertension 61 (6): 1360–83. June 2013. doi:10.1161/HYP.0b013e318293645f. PMID 23608661.

- ↑ "Meditation to Boost Health and Well-Being". https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-lifestyle/mental-health-and-wellbeing/meditation-to-boost-health-and-wellbeing.

- ↑ 158.0 158.1 Davidson, Richard J.; Kaszniak, Alfred W. (October 2015). "Conceptual and Methodological Issues in Research on Mindfulness and Meditation". American Psychologist 70 (7): 581–592. doi:10.1037/a0039512. PMID 26436310.

- ↑ Deolindo, Camila Sardeto; Ribeiro, Mauricio Watanabe; Aratanha, Maria Adelia; Afonso, Rui Ferreira; Irrmischer, Mona; Kozasa, Elisa Harumi (2020-08-07). "A Critical Analysis on Characterizing the Meditation Experience Through the Electroencephalogram". Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 14: 53. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2020.00053. ISSN 1662-5137. PMID 32848645.

External links

|