Biology:Myeloperoxidase: Difference between revisions

imported>Smart bot editor fixing |

fix |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Myeloperoxidase''' ('''MPO''') is a [[Biology:Peroxidase|peroxidase]] [[Biology:Enzyme|enzyme]] that in humans is encoded by the ''MPO'' [[Biology:Gene|gene]] on [[Biology:Chromosome 17|chromosome 17]].<ref name="entrez">{{cite web | title = Entrez Gene: Myeloperoxidase | url = https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene?db=gene&cmd=retrieve&list_uids=4353 }}</ref> MPO is most abundantly expressed in neutrophils (a subtype of [[Biology:White blood cell|white blood cell]]s), and produces hypohalous acids to carry out their [[Biology:Antimicrobial|antimicrobial]] activity, including hypochlorous acid, the sodium salt of which is the chemical in bleach.<ref name="entrez" /><ref name="Klebanoff_2005">{{cite journal | vauthors = Klebanoff SJ | title = Myeloperoxidase: friend and foe | journal = Journal of Leukocyte Biology | volume = 77 | issue = 5 | pages = 598–625 | date = May 2005 | pmid = 15689384 | doi = 10.1189/jlb.1204697 | s2cid = 12489688 | doi-access = free }}</ref> It is a [[Biology:Lysosome|lysosomal]] protein stored in azurophilic granules of the neutrophil and released into the [[Biology:Extracellular space|extracellular space]] during degranulation.<ref name="Kinkade_1983">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kinkade JM, Pember SO, Barnes KC, Shapira R, Spitznagel JK, Martin LE | title = Differential distribution of distinct forms of myeloperoxidase in different azurophilic granule subpopulations from human neutrophils | journal = Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications | volume = 114 | issue = 1 | pages = 296–303 | date = Jul 1983 | pmid = 6192815 | doi = 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91627-3 | bibcode = 1983BBRC..114..296K }}</ref> Neutrophil myeloperoxidase has a [[Biology:Heme|heme]] pigment, which causes its green color in secretions rich in neutrophils, such as [[Biology:Mucus|mucus]] and sputum.<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Le T, Bhushan V, Sochat M, Damisch K, Abrams J, Kallianos K, Boqambar H, Qiu, C, Coleman C | title = First Aid for the USMLE Step 1 | location = New York | pages = 109 | date = 2021 | publisher = McGraw Hill | isbn = 978-1-260-46752-9 | edition = 2021 }}</ref> The green color contributed to its outdated name '''verdoperoxidase'''. | |||

'''Myeloperoxidase''' ('''MPO''') is a [[Biology:Peroxidase|peroxidase]] [[Biology:Enzyme|enzyme]] that in humans is encoded by the ''MPO'' [[Biology:Gene|gene]] on [[Biology:Chromosome 17|chromosome 17]].<ref name="entrez">{{cite web | title = Entrez Gene: Myeloperoxidase | url = https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ | |||

Myeloperoxidase is found in many different organisms including mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians.{{cn|date=January 2024}} Myeloperoxidase deficiency is a well-documented disease among humans resulting in impaired immune function.<ref name=" | Myeloperoxidase is found in many different organisms including mammals, birds, fish,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Castro R, Piazzon MC, Noya M, Leiro JM, Lamas J | title = Isolation and molecular cloning of a fish myeloperoxidase | journal = Molecular Immunology | volume = 45 | issue = 2 | pages = 428–437 | date = January 2008 | pmid = 17659779 | doi = 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.05.028 }}</ref> reptiles, and amphibians.{{cn|date=January 2024}} Myeloperoxidase deficiency is a well-documented disease among humans resulting in impaired immune function.<ref name="Kutter_2000" /> | ||

== | == Structure == | ||

MPO is a | |||

The {{val|150|ul=kDa}} MPO protein is a cationic [[Biology:Tetrameric protein#Homotetramers and heterotetramers|heterotetramer]] consisting of two 15-kDa light chains and two variable-weight glycosylated heavy chains bound to a prosthetic [[Biology:Heme|heme]] group complex with calcium ions, arranged as a homodimer of heterodimers. Both are proteolytically generated from the precursor peptide encoded by the ''MPO'' gene.<ref name="Davey_1996">{{cite journal | vauthors = Davey CA, Fenna RE | title = 2.3 A resolution X-ray crystal structure of the bisubstrate analogue inhibitor salicylhydroxamic acid bound to human myeloperoxidase: a model for a prereaction complex with hydrogen peroxide | journal = Biochemistry | volume = 35 | issue = 33 | pages = 10967–10973 | date = August 1996 | pmid = 8718890 | doi = 10.1021/bi960577m }}</ref><ref name="ELISA">{{cite web | title = Mouse MPO EasyTestTM ELISA Kit | url = http://bioaimscientific.com/sites/default/files/manual/MouseMPOELISA.pdf | access-date = 2015-08-06 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160303172034/http://bioaimscientific.com/sites/default/files/manual/MouseMPOELISA.pdf | archive-date = 2016-03-03 | url-status = dead }}</ref><ref name="MathyHartert_1998">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mathy-Hartert M, Bourgeois E, Grülke S, Deby-Dupont G, Caudron I, Deby C, Lamy M, Serteyn D | title = Purification of myeloperoxidase from equine polymorphonuclear leucocytes | journal = Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research | volume = 62 | issue = 2 | pages = 127–132 | date = April 1998 | pmid = 9553712 | pmc = 1189459 }}</ref><ref name="Davies_2011">{{cite journal | vauthors = Davies MJ | title = Myeloperoxidase-derived oxidation: mechanisms of biological damage and its prevention | journal = Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition | volume = 48 | issue = 1 | pages = 8–19 | date = January 2011 | pmid = 21297906 | pmc = 3022070 | doi = 10.3164/jcbn.11-006FR }}</ref> The light chains are glycosylated and contain the modified iron protoporphyrin IX [[Biology:Active site|active site]]. Together, the light and heavy chains form two identical 73-kDa monomers connected by a [[Chemistry:Cystine|cystine]] bridge at Cys153. The protein forms a deep crevice which holds the heme group at the bottom, as well as a [[Chemistry:Hydrophobic|hydrophobic]] pocket at the entrance to the distal heme cavity which carries out its catalytic activity.<ref name="Davies_2011" /> | |||

Variation in glycosylation and the identity of the heavy chain lead to variations in molecular weight within the 135-200 kDa range.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Shaw SA, Vokits BP, Dilger AK, Viet A, Clark CG, Abell LM, Locke GA, Duke G, Kopcho LM, Dongre A, Gao J, Krishnakumar A, Jusuf S, Khan J, Spronk SA, Basso MD, Zhao L, Cantor GH, Onorato JM, Wexler RR, Duclos F, Kick EK | title = Discovery and structure activity relationships of 7-benzyl triazolopyridines as stable, selective, and reversible inhibitors of myeloperoxidase | journal = Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry | volume = 28 | issue = 22 | article-number = 115723 | date = November 2020 | pmid = 33007547 | doi = 10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115723 | s2cid = 222145838 }}</ref><ref name="Davey_1996" /> In mice, three isoforms exist, differing only by the heavy chain.<ref name="ELISA" /> | |||

One of the ligands is the carbonyl group of Asp 96. Calcium-binding is important for structure of the active site because of Asp 96's close proximity to the catalytic His95 [[Chemistry:Substituent|side chain]].<ref name="Shin_2001">{{cite journal | vauthors = Shin K, Hayasawa H, Lönnerdal B | title = Mutations affecting the calcium-binding site of myeloperoxidase and lactoperoxidase | journal = Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications | volume = 281 | issue = 4 | pages = 1024–1029 | date = Mar 2001 | pmid = 11237766 | doi = 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4448 | bibcode = 2001BBRC..281.1024S }}</ref> | |||

== | === Reaction mechanism === | ||

The central heme group acts as the [[Biology:Active site|active site]]. The reaction starts when hydrogen peroxide donates an oxygen to the heme group, converting it to an activated form called "Compound I". This compound then oxidizes the chloride ions to form the hypochlorous acid and Compound II, which can be reduced back down to its original heme state.{{how|date=January 2024}} This cycle continues for as long as the immune system requires.{{cn|date=January 2024}} | |||

== Function == | |||

MPO is a member of the XPO subfamily of peroxidases and produces [[Chemistry:Hypochlorous acid|hypochlorous acid]] (HOCl) from [[Chemistry:Hydrogen peroxide|hydrogen peroxide]] (H<sub>2</sub>O<sub>2</sub>) and [[Chemistry:Chloride|chloride]] anion (Cl<sup>−</sup>) (or [[Chemistry:Hypobromous acid|hypobromous acid]] if Br- is present) during the [[Biology:Neutrophil|neutrophil]]'s defensive [[Biology:Respiratory burst|respiratory burst]]. It requires heme as a [[Biology:Cofactor (biochemistry)|cofactor]]. Furthermore, it oxidizes [[Chemistry:Tyrosine|tyrosine]] to tyrosyl radical using hydrogen peroxide as an [[Chemistry:Oxidizing agent|oxidizing agent]].<ref name="ELISA" /><ref name="Heinecke_1993">{{cite journal | vauthors = Heinecke JW, Li W, Francis GA, Goldstein JA | title = Tyrosyl radical generated by myeloperoxidase catalyzes the oxidative cross-linking of proteins | journal = The Journal of Clinical Investigation | volume = 91 | issue = 6 | pages = 2866–2872 | date = Jun 1993 | pmid = 8390491 | pmc = 443356 | doi = 10.1172/JCI116531 }}</ref> | |||

However, this hypochlorous acid may also cause oxidative damage in host tissue. Moreover, MPO oxidation of apoA-I reduces HDL-mediated inhibition of [[Biology:Apoptosis|apoptosis]] and inflammation.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Shao B, Oda MN, Oram JF, Heinecke JW | title = Myeloperoxidase: an oxidative pathway for generating dysfunctional high-density lipoprotein | journal = Chemical Research in Toxicology | volume = 23 | issue = 3 | pages = 447–454 | date = Mar 2010 | pmid = 20043647 | pmc = 2838938 | doi = 10.1021/tx9003775 }}</ref> In addition, MPO mediates protein [[Chemistry:Nitrosylation|nitrosylation]] and the formation of 3-chlorotyrosine and [[Chemistry:Dityrosine|dityrosine]] [[Biology:Post-translational modification|post-translational modification]]s.<ref name="ELISA" /> | |||

Myeloperoxidase is the first and so far only{{Update inline|date=January 2025}} human enzyme known to break down [[Physics:Carbon nanotube|carbon nanotube]]s, allaying a concern among clinicians that using nanotubes for targeted delivery of medicines would lead to an unhealthy buildup of nanotubes in tissues.<ref name="Kagan_2010">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kagan VE, Konduru NV, Feng W, Allen BL, Conroy J, Volkov Y, Vlasova II, Belikova NA, Yanamala N, Kapralov A, Tyurina YY, Shi J, Kisin ER, Murray AR, Franks J, Stolz D, Gou P, Klein-Seetharaman J, Fadeel B, Star A, Shvedova AA | title = Carbon nanotubes degraded by neutrophil myeloperoxidase induce less pulmonary inflammation | journal = Nature Nanotechnology | volume = 5 | issue = 5 | pages = 354–359 | date = May 2010 | pmid = 20364135 | pmc = 6714564 | doi = 10.1038/nnano.2010.44 | bibcode = 2010NatNa...5..354K }} | |||

*{{cite magazine | vauthors = Dillow C | title = Scientists Devise A Means For Human Bodies To Break Down Carbon Nanotubes | date = April 6, 2010 | magazine = Popular Science | url = http://www.popsci.com/science/article/2010-04/enzyme-blood-cells-breaks-down-carbon-nanotubes-paving-way-nano-delivered-drugs }}</ref> | |||

=== | === Role in innate immunity === | ||

[[Biology:Neutrophil|Neutrophils]] use myeloperoxidase to produce the substances needed for their respiratory burst.<ref name="Aratani_2018">{{Cite journal | vauthors = Aratani Y | title = Myeloperoxidase: Its role for host defense, inflammation, and neutrophil function | journal = Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics | volume = 640 | pages = 47–52 | date = 2018-02-15 | pmid = 29336940 | doi = 10.1016/j.abb.2018.01.004 | url = https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0003986117307725 | issn = 0003-9861 | url-access = subscription }}</ref> Hypochlorous acid and tyrosyl radical are cytotoxic, so they are used by the neutrophil to kill [[Biology:Bacteria|bacteria]] and certain types of fungi.<ref name="Aratani_2018" /><ref name="Hampton_1998">{{cite journal | vauthors = Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC | title = Inside the neutrophil phagosome: oxidants, myeloperoxidase, and bacterial killing | journal = Blood | volume = 92 | issue = 9 | pages = 3007–3017 | date = Nov 1998 | pmid = 9787133 | doi = 10.1182/blood.V92.9.3007 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Davies MJ | title = Myeloperoxidase: Mechanisms, reactions and inhibition as a therapeutic strategy in inflammatory diseases | journal = Pharmacology & Therapeutics | volume = 218 | article-number = 107685 | date = February 2021 | pmid = 32961264 | doi = 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107685 | s2cid = 221865058 }}</ref> | |||

== Clinical significance == | == Clinical significance == | ||

Myeloperoxidase deficiency is a hereditary deficiency of the enzyme, which | === Myeloperoxidase deficiency === | ||

Myeloperoxidase deficiency is a hereditary deficiency of the enzyme, which causes a mild immune deficiency against certain [[Medicine:Pathogen|pathogens]].<ref name="Kutter_2000">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kutter D, Devaquet P, Vanderstocken G, Paulus JM, Marchal V, Gothot A | title = Consequences of total and subtotal myeloperoxidase deficiency: risk or benefit ? | journal = Acta Haematologica | volume = 104 | issue = 1 | pages = 10–15 | year = 2000 | pmid = 11111115 | doi = 10.1159/000041062 | s2cid = 36776058 }}</ref><ref name="Aratani_2018" /> People with myeloperoxidase deficiency are most at risk of infection by ''[[Biology:Candida (fungus)|Candida]]'' species, which are pathogenic fungi. The most common species found in humans is ''[[Biology:Candida albicans|Candida albicans]]''. There may be an increased risk of certain other infections, such as with ''[[Biology:Klebsiella pneumoniae|Klebsiella pneumoniae]]'', but recurrent [[Medicine:Candidiasis|candidiasis]] is the only common clinical consequence, if the patient is noticeably affected at all.<ref name="Aratani_2018" /> | |||

[[Biology:Antibody|Antibodies]] against MPO have been implicated in various types of [[Medicine:Vasculitis|vasculitis]], most prominently three clinically and pathologically recognized forms: [[Medicine:Granulomatosis with polyangiitis|granulomatosis with polyangiitis]] (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA); and [[Medicine:Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis|eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis]] (EGPA). Antibodies are also known as [[Chemistry:Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody|anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies]] (ANCAs), though ANCAs have also been detected in [[Staining|staining]] of the perinuclear region.<ref name=" | === Vasculitis === | ||

[[Biology:Antibody|Antibodies]] against MPO have been implicated in various types of [[Medicine:Vasculitis|vasculitis]], most prominently three clinically and pathologically recognized forms: [[Medicine:Granulomatosis with polyangiitis|granulomatosis with polyangiitis]] (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA); and [[Medicine:Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis|eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis]] (EGPA). Antibodies are also known as [[Chemistry:Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody|anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies]] (ANCAs), though ANCAs have also been detected in [[Staining|staining]] of the perinuclear region.<ref name="Flint_2015">{{cite journal | vauthors = Flint SM, McKinney EF, Smith KG | title = Emerging concepts in the pathogenesis of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis | journal = Current Opinion in Rheumatology | volume = 27 | issue = 2 | pages = 197–203 | date = Mar 2015 | pmid = 25629443 | doi = 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000145 | s2cid = 20296651 | url = https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/247422 }}</ref> | |||

=== Atherosclerosis and heart disease === | |||

Myeloperoxidase is known to contribute to [[Medicine:Atherosclerosis|atherosclerosis]] and diseases related to it, including [[Medicine:Coronary artery disease|coronary artery disease]]. MPO oxidizes [[Medicine:Low-density lipoprotein|LDL cholesterol]], and as a result, the [[Biology:LDL receptor|LDL receptor]] in liver cells becomes unable to bind to LDL and remove it from the blood stream. However, in its oxidized state, LDL can still contribute to [[Biology:Foam cell|foam cell]] formation and other atherosclerotic processes. Thus, elevated levels of MPO are a risk factor for atherosclerosis.<ref>{{Cite journal | vauthors = Frangie C, Daher J | title = Role of myeloperoxidase in inflammation and atherosclerosis (Review) | journal = Biomedical Reports | volume = 16 | issue = 6 | article-number = 53 | date = 2022-05-06 | pmid = 35620311 | pmc = 9112398 | doi = 10.3892/br.2022.1536 | issn = 2049-9434 }}</ref> | |||

=== Medical tests === | === Medical tests === | ||

{{Update|part=section|date=January 2025}} | |||

An initial 2003 study suggested that MPO could serve as a sensitive predictor for [[Medicine:Myocardial infarction|myocardial infarction]] in patients presenting with [[Medicine:Chest pain|chest pain]].<ref name="Brennan_2003">{{cite journal | vauthors = Brennan ML, Penn MS, Van Lente F, Nambi V, Shishehbor MH, Aviles RJ, Goormastic M, Pepoy ML, McErlean ES, Topol EJ, Nissen SE, Hazen SL | title = Prognostic value of myeloperoxidase in patients with chest pain | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 349 | issue = 17 | pages = 1595–1604 | date = Oct 2003 | pmid = 14573731 | doi = 10.1056/NEJMoa035003 | s2cid = 22084078 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Since then, there have been over 100 published studies documenting the utility of MPO testing. The 2010 Heslop et al. study reported that measuring both MPO and CRP (C-reactive protein; a general and cardiac-related marker of inflammation) provided added benefit for risk prediction than just measuring CRP alone.<ref name="Heslop_2010">{{cite journal | vauthors = Heslop CL, Frohlich JJ, Hill JS | title = Myeloperoxidase and C-reactive protein have combined utility for long-term prediction of cardiovascular mortality after coronary angiography | journal = Journal of the American College of Cardiology | volume = 55 | issue = 11 | pages = 1102–1109 | date = Mar 2010 | pmid = 20223364 | doi = 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.050 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

[[Biology:Immunohistochemistry|Immunohistochemical]] staining for myeloperoxidase used to be administered in the diagnosis of [[Medicine:Acute myeloid leukemia|acute myeloid leukemia]] to demonstrate that the leukemic cells were derived from the myeloid lineage. Myeloperoxidase staining is still important in the diagnosis of myeloid sarcoma, contrasting with the negative staining of [[Medicine:Lymphoma|lymphoma]]s, which can otherwise have a similar appearance.<ref name="Leong_2003">{{cite book | vauthors = Leong AS, Cooper K, Leong, FJ | title = Manual of Diagnostic Antibodies for Immunohistology | location = London | pages = 325–326 | year = 2003 | publisher = Greenwich Medical Media | isbn = 978-1-84110-100-2 }}</ref> In the case of screening patients for vasculitis, [[Biology:Flow cytometry|flow cytometric assays]] have demonstrated comparable sensitivity to [[Biology:Immunofluorescence|immunofluorescence]] tests, with the additional benefit of simultaneous detection of multiple autoantibodies relevant to vasculitis. Nonetheless, this method still requires further testing.<ref name="Csernok_2014">{{cite journal | vauthors = Csernok E, Moosig F | title = Current and emerging techniques for ANCA detection in vasculitis | journal = Nature Reviews. Rheumatology | volume = 10 | issue = 8 | pages = 494–501 | date = Aug 2014 | pmid = 24890776 | doi = 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.78 | s2cid = 25292707 }}</ref> | |||

[[Biology:Immunohistochemistry|Immunohistochemical]] staining for myeloperoxidase used to be administered in the diagnosis of [[Medicine:Acute myeloid leukemia|acute myeloid leukemia]] to demonstrate that the leukemic cells were derived from the myeloid lineage. Myeloperoxidase staining is still important in the diagnosis of myeloid sarcoma, contrasting with the negative staining of [[Medicine:Lymphoma|lymphoma]]s, which can otherwise have a similar appearance.<ref name = "Leong_2003">{{cite book |vauthors=Leong AS, Cooper K, Leong, FJ | title = Manual of Diagnostic Antibodies for Immunohistology | | |||

=== Inhibitors | === Inhibitors === | ||

[[Chemistry:Azide|Azide]] has been used traditionally as an MPO inhibitor, but 4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide (4-ABH) is a more specific inhibitor of MPO.<ref name=" | [[Chemistry:Azide|Azide]] has been used traditionally as an MPO inhibitor, but 4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide (4-ABH) is a more specific inhibitor of MPO.<ref name="Kettle_1997">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kettle AJ, Gedye CA, Winterbourn CC | title = Mechanism of inactivation of myeloperoxidase by 4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide | journal = The Biochemical Journal | volume = 321 | issue = Pt 2 | pages = 503–508 | date = Jan 1997 | pmid = 9020887 | pmc = 1218097 | doi = 10.1042/bj3210503 | series = 321 }}</ref> | ||

== See also == | == See also == | ||

Latest revision as of 02:35, 21 January 2026

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) is a peroxidase enzyme that in humans is encoded by the MPO gene on chromosome 17.[1] MPO is most abundantly expressed in neutrophils (a subtype of white blood cells), and produces hypohalous acids to carry out their antimicrobial activity, including hypochlorous acid, the sodium salt of which is the chemical in bleach.[1][2] It is a lysosomal protein stored in azurophilic granules of the neutrophil and released into the extracellular space during degranulation.[3] Neutrophil myeloperoxidase has a heme pigment, which causes its green color in secretions rich in neutrophils, such as mucus and sputum.[4] The green color contributed to its outdated name verdoperoxidase.

Myeloperoxidase is found in many different organisms including mammals, birds, fish,[5] reptiles, and amphibians.[citation needed] Myeloperoxidase deficiency is a well-documented disease among humans resulting in impaired immune function.[6]

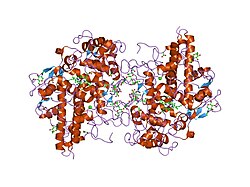

Structure

The 150 kDa MPO protein is a cationic heterotetramer consisting of two 15-kDa light chains and two variable-weight glycosylated heavy chains bound to a prosthetic heme group complex with calcium ions, arranged as a homodimer of heterodimers. Both are proteolytically generated from the precursor peptide encoded by the MPO gene.[7][8][9][10] The light chains are glycosylated and contain the modified iron protoporphyrin IX active site. Together, the light and heavy chains form two identical 73-kDa monomers connected by a cystine bridge at Cys153. The protein forms a deep crevice which holds the heme group at the bottom, as well as a hydrophobic pocket at the entrance to the distal heme cavity which carries out its catalytic activity.[10]

Variation in glycosylation and the identity of the heavy chain lead to variations in molecular weight within the 135-200 kDa range.[11][7] In mice, three isoforms exist, differing only by the heavy chain.[8]

One of the ligands is the carbonyl group of Asp 96. Calcium-binding is important for structure of the active site because of Asp 96's close proximity to the catalytic His95 side chain.[12]

Reaction mechanism

The central heme group acts as the active site. The reaction starts when hydrogen peroxide donates an oxygen to the heme group, converting it to an activated form called "Compound I". This compound then oxidizes the chloride ions to form the hypochlorous acid and Compound II, which can be reduced back down to its original heme state. This cycle continues for as long as the immune system requires.[citation needed]

Function

MPO is a member of the XPO subfamily of peroxidases and produces hypochlorous acid (HOCl) from hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and chloride anion (Cl−) (or hypobromous acid if Br- is present) during the neutrophil's defensive respiratory burst. It requires heme as a cofactor. Furthermore, it oxidizes tyrosine to tyrosyl radical using hydrogen peroxide as an oxidizing agent.[8][13]

However, this hypochlorous acid may also cause oxidative damage in host tissue. Moreover, MPO oxidation of apoA-I reduces HDL-mediated inhibition of apoptosis and inflammation.[14] In addition, MPO mediates protein nitrosylation and the formation of 3-chlorotyrosine and dityrosine post-translational modifications.[8]

Myeloperoxidase is the first and so far only[needs update] human enzyme known to break down carbon nanotubes, allaying a concern among clinicians that using nanotubes for targeted delivery of medicines would lead to an unhealthy buildup of nanotubes in tissues.[15]

Role in innate immunity

Neutrophils use myeloperoxidase to produce the substances needed for their respiratory burst.[16] Hypochlorous acid and tyrosyl radical are cytotoxic, so they are used by the neutrophil to kill bacteria and certain types of fungi.[16][17][18]

Clinical significance

Myeloperoxidase deficiency

Myeloperoxidase deficiency is a hereditary deficiency of the enzyme, which causes a mild immune deficiency against certain pathogens.[6][16] People with myeloperoxidase deficiency are most at risk of infection by Candida species, which are pathogenic fungi. The most common species found in humans is Candida albicans. There may be an increased risk of certain other infections, such as with Klebsiella pneumoniae, but recurrent candidiasis is the only common clinical consequence, if the patient is noticeably affected at all.[16]

Vasculitis

Antibodies against MPO have been implicated in various types of vasculitis, most prominently three clinically and pathologically recognized forms: granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA); and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). Antibodies are also known as anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs), though ANCAs have also been detected in staining of the perinuclear region.[19]

Atherosclerosis and heart disease

Myeloperoxidase is known to contribute to atherosclerosis and diseases related to it, including coronary artery disease. MPO oxidizes LDL cholesterol, and as a result, the LDL receptor in liver cells becomes unable to bind to LDL and remove it from the blood stream. However, in its oxidized state, LDL can still contribute to foam cell formation and other atherosclerotic processes. Thus, elevated levels of MPO are a risk factor for atherosclerosis.[20]

Medical tests

| Parts of this biology (those related to section) need to be updated. Please update this biology to reflect recent events or newly available information. (January 2025) |

An initial 2003 study suggested that MPO could serve as a sensitive predictor for myocardial infarction in patients presenting with chest pain.[21] Since then, there have been over 100 published studies documenting the utility of MPO testing. The 2010 Heslop et al. study reported that measuring both MPO and CRP (C-reactive protein; a general and cardiac-related marker of inflammation) provided added benefit for risk prediction than just measuring CRP alone.[22]

Immunohistochemical staining for myeloperoxidase used to be administered in the diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia to demonstrate that the leukemic cells were derived from the myeloid lineage. Myeloperoxidase staining is still important in the diagnosis of myeloid sarcoma, contrasting with the negative staining of lymphomas, which can otherwise have a similar appearance.[23] In the case of screening patients for vasculitis, flow cytometric assays have demonstrated comparable sensitivity to immunofluorescence tests, with the additional benefit of simultaneous detection of multiple autoantibodies relevant to vasculitis. Nonetheless, this method still requires further testing.[24]

Inhibitors

Azide has been used traditionally as an MPO inhibitor, but 4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide (4-ABH) is a more specific inhibitor of MPO.[25]

See also

- Chloroma

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Entrez Gene: Myeloperoxidase". https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene?db=gene&cmd=retrieve&list_uids=4353.

- ↑ "Myeloperoxidase: friend and foe". Journal of Leukocyte Biology 77 (5): 598–625. May 2005. doi:10.1189/jlb.1204697. PMID 15689384.

- ↑ "Differential distribution of distinct forms of myeloperoxidase in different azurophilic granule subpopulations from human neutrophils". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 114 (1): 296–303. Jul 1983. doi:10.1016/0006-291x(83)91627-3. PMID 6192815. Bibcode: 1983BBRC..114..296K.

- ↑ First Aid for the USMLE Step 1 (2021 ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. 2021. pp. 109. ISBN 978-1-260-46752-9.

- ↑ "Isolation and molecular cloning of a fish myeloperoxidase". Molecular Immunology 45 (2): 428–437. January 2008. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2007.05.028. PMID 17659779.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Consequences of total and subtotal myeloperoxidase deficiency: risk or benefit ?". Acta Haematologica 104 (1): 10–15. 2000. doi:10.1159/000041062. PMID 11111115.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "2.3 A resolution X-ray crystal structure of the bisubstrate analogue inhibitor salicylhydroxamic acid bound to human myeloperoxidase: a model for a prereaction complex with hydrogen peroxide". Biochemistry 35 (33): 10967–10973. August 1996. doi:10.1021/bi960577m. PMID 8718890.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "Mouse MPO EasyTestTM ELISA Kit". http://bioaimscientific.com/sites/default/files/manual/MouseMPOELISA.pdf.

- ↑ "Purification of myeloperoxidase from equine polymorphonuclear leucocytes". Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research 62 (2): 127–132. April 1998. PMID 9553712.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Myeloperoxidase-derived oxidation: mechanisms of biological damage and its prevention". Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition 48 (1): 8–19. January 2011. doi:10.3164/jcbn.11-006FR. PMID 21297906.

- ↑ "Discovery and structure activity relationships of 7-benzyl triazolopyridines as stable, selective, and reversible inhibitors of myeloperoxidase". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 28 (22). November 2020. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115723. PMID 33007547.

- ↑ "Mutations affecting the calcium-binding site of myeloperoxidase and lactoperoxidase". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 281 (4): 1024–1029. Mar 2001. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2001.4448. PMID 11237766. Bibcode: 2001BBRC..281.1024S.

- ↑ "Tyrosyl radical generated by myeloperoxidase catalyzes the oxidative cross-linking of proteins". The Journal of Clinical Investigation 91 (6): 2866–2872. Jun 1993. doi:10.1172/JCI116531. PMID 8390491.

- ↑ "Myeloperoxidase: an oxidative pathway for generating dysfunctional high-density lipoprotein". Chemical Research in Toxicology 23 (3): 447–454. Mar 2010. doi:10.1021/tx9003775. PMID 20043647.

- ↑ "Carbon nanotubes degraded by neutrophil myeloperoxidase induce less pulmonary inflammation". Nature Nanotechnology 5 (5): 354–359. May 2010. doi:10.1038/nnano.2010.44. PMID 20364135. Bibcode: 2010NatNa...5..354K.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 "Myeloperoxidase: Its role for host defense, inflammation, and neutrophil function". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 640: 47–52. 2018-02-15. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2018.01.004. ISSN 0003-9861. PMID 29336940. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0003986117307725.

- ↑ "Inside the neutrophil phagosome: oxidants, myeloperoxidase, and bacterial killing". Blood 92 (9): 3007–3017. Nov 1998. doi:10.1182/blood.V92.9.3007. PMID 9787133.

- ↑ "Myeloperoxidase: Mechanisms, reactions and inhibition as a therapeutic strategy in inflammatory diseases". Pharmacology & Therapeutics 218. February 2021. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107685. PMID 32961264.

- ↑ "Emerging concepts in the pathogenesis of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis". Current Opinion in Rheumatology 27 (2): 197–203. Mar 2015. doi:10.1097/BOR.0000000000000145. PMID 25629443. https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/247422.

- ↑ "Role of myeloperoxidase in inflammation and atherosclerosis (Review)". Biomedical Reports 16 (6). 2022-05-06. doi:10.3892/br.2022.1536. ISSN 2049-9434. PMID 35620311.

- ↑ "Prognostic value of myeloperoxidase in patients with chest pain". The New England Journal of Medicine 349 (17): 1595–1604. Oct 2003. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa035003. PMID 14573731.

- ↑ "Myeloperoxidase and C-reactive protein have combined utility for long-term prediction of cardiovascular mortality after coronary angiography". Journal of the American College of Cardiology 55 (11): 1102–1109. Mar 2010. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.050. PMID 20223364.

- ↑ Manual of Diagnostic Antibodies for Immunohistology. London: Greenwich Medical Media. 2003. pp. 325–326. ISBN 978-1-84110-100-2.

- ↑ "Current and emerging techniques for ANCA detection in vasculitis". Nature Reviews. Rheumatology 10 (8): 494–501. Aug 2014. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2014.78. PMID 24890776.

- ↑ "Mechanism of inactivation of myeloperoxidase by 4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide". The Biochemical Journal. 321 321 (Pt 2): 503–508. Jan 1997. doi:10.1042/bj3210503. PMID 9020887.

External links

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P05164 (Myeloperoxidase) at the PDBe-KB.

|