Error function: Difference between revisions

over-write |

over-write |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Sigmoid shape special function}} | {{Short description|Sigmoid shape special function}} | ||

{{Distinguish|Loss function}} | |||

In mathematics, the '''error function''' (also called the '''Gauss error function'''), often denoted by '''{{math|erf}}''', is a function <math>\mathrm{erf}: \mathbb{C} \to \mathbb{C}</math> defined as:<ref>{{cite book|last =Andrews|first = Larry C.|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=2CAqsF-RebgC&pg=PA110 |title = Special functions of mathematics for engineers|page = 110|publisher = SPIE Press |date= 1998|isbn = 9780819426161}}</ref> | |||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf}(z) = \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi}\int_0^z e^{-t^2}\,dt.</math> | |||

{{Infobox mathematical function | {{Infobox mathematical function | ||

| name = Error function | | name = Error function | ||

| image = Error Function.svg | | image = Error Function.svg | ||

| imagesize = 400px | | imagesize = 400px | ||

| imagealt = Plot of the error function | | imagealt = Plot of the error function over real numbers | ||

| caption = Plot of the error function | | caption = Plot of the error function over real numbers | ||

| general_definition = <math>\operatorname{erf} z = \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi}\int_0^z e^{-t^2}\,\mathrm dt</math> | | general_definition = <math>\operatorname{erf}(z) = \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi}\int_0^z e^{-t^2}\,\mathrm dt</math> | ||

| fields_of_application = Probability, thermodynamics, digital communications | | fields_of_application = Probability, thermodynamics, digital communications | ||

| domain = <math>\mathbb{ | | domain = <math>\mathbb{C}</math> | ||

| range = <math>\left( -1,1 \right)</math> | | range = <math>\left( -1,1 \right)</math> | ||

| parity = Odd | | parity = Odd | ||

| root = 0 | | root = 0 | ||

| derivative = <math>\frac{ | | derivative = <math>\frac{d}{dz}\operatorname{erf}(z) = \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} e^{-z^2} </math> | ||

| antiderivative = <math>\int \operatorname{erf} z\,dz = z \operatorname{erf} z + \frac{e^{-z^2}}{\sqrt\pi} + C</math> | | antiderivative = <math>\int \operatorname{erf}(z)\,dz = z \operatorname{erf}(z) + \frac{e^{-z^2}}{\sqrt\pi} + C</math> | ||

| taylor_series = <math>\operatorname{erf} z = \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{ | | taylor_series = <math>\operatorname{erf}(z) = \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n}{2n+1} \frac{z^{2n+1}}{n!}</math> | ||

}} | }} | ||

The integral here is a complex [[Contour integration|contour integral]] which is path-independent because <math>\exp(-t^2)</math> is [[Holomorphic function|holomorphic]] on the whole complex plane <math>\mathbb{C}</math>. In many applications, the function argument is a [[Real number|real number]], in which case the function value is also real. | |||

In some old texts,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Whittaker |first1=Edmund Taylor |title=A Course of Modern Analysis |title-link=A Course of Modern Analysis |last2=Watson |first2=George Neville |date=2021 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-316-51893-9 |editor-last=Moll |editor-first=Victor Hugo |edition=5th revised |page=358 |}}</ref> | |||

the error function is defined without the factor of <math>\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}</math>. | |||

This [[Nonelementary integral|nonelementary integral]] is a [[Sigmoid function|sigmoid]] function that occurs often in [[Probability|probability]], [[Statistics|statistics]], and [[Partial differential equation|partial differential equation]]s. | |||

In statistics, for non-negative real values of {{mvar|x}}, the error function has the following interpretation: for a real [[Random variable|random variable]] {{mvar|Y}} that is [[Normal distribution|normally distributed]] with [[Mean|mean]] 0 and [[Standard deviation|standard deviation]] <math>\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}</math>, {{math|erf(''x'')}} is the probability that {{mvar|Y}} falls in the range {{closed-closed|−''x'', ''x''}}. | |||

Two closely related functions are the '''complementary error function''' <math>\mathrm{erfc}: \mathbb{C} \to \mathbb{C}</math> is defined as | |||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erfc}(z) = 1 - \operatorname{erf}(z),</math> | |||

and the '''imaginary error function''' <math>\mathrm{erfi}: \mathbb{C} \to \mathbb{C}</math> is defined as | |||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erfi}(z) = -i\operatorname{erf}(iz),</math> | |||

where {{mvar|i}} is the [[Imaginary unit|imaginary unit]]. | where {{mvar|i}} is the [[Imaginary unit|imaginary unit]]. | ||

| Line 42: | Line 41: | ||

The name "error function" and its abbreviation {{math|erf}} were proposed by [[Biography:James Whitbread Lee Glaisher|J. W. L. Glaisher]] in 1871 on account of its connection with "the theory of Probability, and notably the theory of [[Errors and residuals|Errors]]."<ref name="Glaisher1871a">{{cite journal|last1=Glaisher|first1=James Whitbread Lee|title= On a class of definite integrals|journal=London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science|date=July 1871 |volume=42 |pages=294–302|access-date=6 December 2017|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8Po7AQAAMAAJ&pg=RA1-PA294 |number=277 |series=4 |doi=10.1080/14786447108640568}}</ref> The error function complement was also discussed by Glaisher in a separate publication in the same year.<ref name="Glaisher1871b">{{cite journal|last1=Glaisher|first1=James Whitbread Lee|title=On a class of definite integrals. Part II|journal=London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science|date=September 1871 |volume=42|pages=421–436|access-date=6 December 2017|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yJ1YAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA421 |series=4 |number=279 |doi=10.1080/14786447108640600}}</ref> | The name "error function" and its abbreviation {{math|erf}} were proposed by [[Biography:James Whitbread Lee Glaisher|J. W. L. Glaisher]] in 1871 on account of its connection with "the theory of Probability, and notably the theory of [[Errors and residuals|Errors]]."<ref name="Glaisher1871a">{{cite journal|last1=Glaisher|first1=James Whitbread Lee|title= On a class of definite integrals|journal=London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science|date=July 1871 |volume=42 |pages=294–302|access-date=6 December 2017|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8Po7AQAAMAAJ&pg=RA1-PA294 |number=277 |series=4 |doi=10.1080/14786447108640568}}</ref> The error function complement was also discussed by Glaisher in a separate publication in the same year.<ref name="Glaisher1871b">{{cite journal|last1=Glaisher|first1=James Whitbread Lee|title=On a class of definite integrals. Part II|journal=London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science|date=September 1871 |volume=42|pages=421–436|access-date=6 December 2017|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yJ1YAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA421 |series=4 |number=279 |doi=10.1080/14786447108640600}}</ref> | ||

For the "law of facility" of errors whose density is given by | For the "law of facility" of errors whose density is given by | ||

<math display="block">f(x) = \left(\frac{c}{\pi}\right)^{1/2} e^{-c x^2}</math> | |||

(the [[Normal distribution|normal distribution]]), Glaisher calculates the probability of an error lying between {{mvar|p}} and {{mvar|q}} as: | (the [[Normal distribution|normal distribution]]), Glaisher calculates the probability of an error lying between {{mvar|p}} and {{mvar|q}} as: | ||

<math display="block">\left(\frac{c}{\pi}\right)^\frac{1}{2} \int_p^qe^{-cx^2}\,dx = \tfrac{1}{2}\left(\operatorname{erf} \left(q\sqrt{c}\right) -\operatorname{erf} \left(p\sqrt{c}\right)\right).</math> | |||

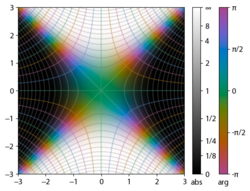

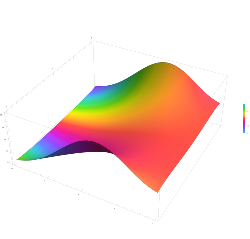

[[File:Plot of the error function Erf(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D.svg|alt=Plot of the error function erf(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D|thumb|Plot of the error function erf(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D]] | |||

==Applications== | ==Applications== | ||

| Line 54: | Line 51: | ||

The error and complementary error functions occur, for example, in solutions of the [[Heat equation|heat equation]] when boundary conditions are given by the [[Heaviside step function]]. | The error and complementary error functions occur, for example, in solutions of the [[Heat equation|heat equation]] when boundary conditions are given by the [[Heaviside step function]]. | ||

The error function and its approximations can be used to estimate results that hold [[With high probability|with high probability]] or with low probability. Given a random variable {{math|''X'' ~ Norm[''μ'',''σ'']}} (a normal distribution with mean {{mvar|μ}} and standard deviation {{mvar|σ}}) and a constant {{math|''L'' > ''μ''}}, it can be shown via integration by substitution: | The error function and its approximations can be used to estimate results that hold [[With high probability|with high probability]] or with low probability. Given a random variable {{math|''X'' ~ Norm[''μ'',''σ'']}} (a normal distribution with mean {{mvar|μ}} and standard deviation {{mvar|σ}}) and a constant {{math|''L'' > ''μ''}}, it can be shown via [[Integration by substitution|integration by substitution]]: | ||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

\Pr[X\leq L] &= \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2} \operatorname{erf}\left(\frac{L-\mu}{\sqrt{2}\sigma}\right) \\ | |||

\Pr[X\leq L] &= \ | &\approx A \exp \left(-B \left(\frac{L-\mu}{\sigma}\right)^2\right) | ||

&\approx A \exp \left(-B \left(\frac{L-\mu}{\sigma}\right)^2\right) \end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

where {{mvar|A}} and {{mvar|B}} are certain numeric constants. If {{mvar|L}} is sufficiently far from the mean, specifically {{math|''μ'' − ''L'' ≥ ''σ''{{sqrt|ln ''k''}}}}, then: | where {{mvar|A}} and {{mvar|B}} are certain numeric constants. If {{mvar|L}} is sufficiently far from the mean, specifically {{math|''μ'' − ''L'' ≥ ''σ''{{sqrt|ln(''k'')}}}}, then: | ||

<math display="block">\Pr[X\leq L] \leq A \exp (-B \ln(k)) = \frac{A}{k^B}</math> | |||

so the probability goes to 0 as {{math|''k'' → ∞}}. | so the probability goes to 0 as {{math|''k'' → ∞}}. | ||

The probability for {{mvar|X}} being in the interval {{closed-closed|''L<sub>a</sub>'', ''L<sub>b</sub>''}} can be derived as | The probability for {{mvar|X}} being in the interval {{closed-closed|''L<sub>a</sub>'', ''L<sub>b</sub>''}} can be derived as | ||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

\Pr[L_a\leq X \leq L_b] &= \int_{L_a}^{L_b} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma} \exp\left(-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \, | \Pr[L_a\leq X \leq L_b] &= \int_{L_a}^{L_b} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma} \exp\left(-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \, dx \\ | ||

&= \ | &= \frac{1}{2}\left(\operatorname{erf}\left(\frac{L_b-\mu}{\sqrt{2}\sigma}\right) - \operatorname{erf}\left(\frac{L_a-\mu}{\sqrt{2}\sigma}\right)\right).\end{align}</math> | ||

==Properties== | ==Properties== | ||

| Line 79: | Line 76: | ||

| caption1 = Integrand {{math|exp(−''z''<sup>2</sup>)}} | | caption1 = Integrand {{math|exp(−''z''<sup>2</sup>)}} | ||

| image2 = ComplexErfz.png | | image2 = ComplexErfz.png | ||

| caption2 = {{math|erf ''z''}} | | caption2 = {{math|erf(''z'')}} | ||

}} | }} | ||

The property {{math|erf (−''z'') | The property {{math|1=erf (−''z'') = −erf(''z'')}} means that the error function is an [[Even and odd functions|odd function]]. This directly results from the fact that the integrand {{math|''e''<sup>−''t''<sup>2</sup></sup>}} is an [[Even function|even function]] (the antiderivative of an even function which is zero at the origin is an odd function and vice versa). | ||

Since the error function is an [[Entire function|entire function]] which takes real numbers to real numbers, for any [[Complex number|complex number]] {{mvar|z}}: | Since the error function is an [[Entire function|entire function]] which takes real numbers to real numbers, for any [[Complex number|complex number]] {{mvar|z}}: | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf}(\overline{z}) = \overline{\operatorname{erf}(z)} </math> | |||

where <math>\overline{z} | |||

</math> denotes the [[Complex conjugate|complex conjugate]] of <math>z</math>. | |||

The integrand {{math|1=''f'' = exp(−''z''<sup>2</sup>)}} and {{math|1=''f'' = erf(''z'')}} are shown in the complex {{mvar|z}}-plane in the figures at right with [[Domain coloring|domain coloring]]. | |||

The integrand {{math|''f'' | |||

The error function at {{math|+∞}} is exactly 1 (see [[Gaussian integral]]). At the real axis, {{math|erf ''z''}} approaches unity at {{math|''z'' → +∞}} and −1 at {{math|''z'' → −∞}}. At the imaginary axis, it tends to {{math|±''i''∞}}. | The error function at {{math|+∞}} is exactly 1 (see [[Gaussian integral]]). At the real axis, {{math|erf ''z''}} approaches unity at {{math|''z'' → +∞}} and −1 at {{math|''z'' → −∞}}. At the imaginary axis, it tends to {{math|±''i''∞}}. | ||

<!-- ; the relation {{math|erf(−''z'') | <!-- ; the relation {{math|1=erf(−''z'') = −erf ''z''}} holds.!--> | ||

===Taylor series=== | ===Taylor series=== | ||

The error function is an [[Entire function|entire function]]; it has no singularities (except that at infinity) and its Taylor expansion always converges | The error function is an [[Entire function|entire function]]; it has no singularities (except that at infinity) and its Taylor expansion always converges. For {{math|''x'' >> 1}}, however, cancellation of leading terms makes the Taylor expansion unpractical. | ||

The defining integral cannot be evaluated in [[Closed-form expression|closed form]] in terms of elementary functions (see [[Liouville's theorem (differential algebra)|Liouville's theorem]]), but by expanding the integrand {{math|''e''<sup>−''z''<sup>2</sup></sup>}} into its [[Maclaurin series]] and integrating term by term, one obtains the error function's Maclaurin series as: | The defining integral cannot be evaluated in [[Closed-form expression|closed form]] in terms of elementary functions (see [[Liouville's theorem (differential algebra)|Liouville's theorem]]), but by expanding the integrand {{math|''e''<sup>−''z''<sup>2</sup></sup>}} into its [[Maclaurin series]] and integrating term by term, one obtains the error function's Maclaurin series as: | ||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

\operatorname{erf}(z) | |||

&= \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi}\sum_{n=0}^\infty\frac{(-1)^n z^{2n+1}}{n! (2n+1)} \\[6pt] | &= \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi}\sum_{n=0}^\infty\frac{(-1)^n z^{2n+1}}{n! (2n+1)} \\[6pt] | ||

&=\frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \left(z-\frac{z^3}{3}+\frac{z^5}{10}-\frac{z^7}{42}+\frac{z^9}{216}-\cdots\right) | &= \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \left(z-\frac{z^3}{3}+\frac{z^5}{10}-\frac{z^7}{42}+\frac{z^9}{216}-\cdots\right) | ||

\end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

which holds for every [[Complex number|complex number]] {{mvar|z}}. The denominator terms are sequence A007680 in the OEIS. | |||

It is a special case of [[Confluent hypergeometric function|Kummer's function]]: | |||

<math> | |||

\operatorname{erf}(z) = \frac{2z}{\surd \pi}{}_1F_1(1/2;3/2;-z^2). | |||

</math> | |||

For iterative calculation of the above series, the following alternative formulation may be useful: | For iterative calculation of the above series, the following alternative formulation may be useful: | ||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

\operatorname{erf}(z) | |||

&= \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi}\sum_{n=0}^\infty\left(z \prod_{k=1}^n {\frac{-(2k-1) z^2}{k (2k+1)}}\right) \\[6pt] | &= \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi}\sum_{n=0}^\infty\left(z \prod_{k=1}^n {\frac{-(2k-1) z^2}{k (2k+1)}}\right) \\[6pt] | ||

&= \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{z}{2n+1} \prod_{k=1}^n \frac{-z^2}{k} | &= \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{z}{2n+1} \prod_{k=1}^n \frac{-z^2}{k} | ||

\end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

because {{math|{{sfrac|−(2''k'' − 1)''z''<sup>2</sup>|''k''(2''k'' + 1)}}}} expresses the multiplier to turn the {{mvar|k}}th term into the {{math|(''k'' + 1)}}th term (considering {{mvar|z}} as the first term). | because {{math|{{sfrac|−(2''k'' − 1)''z''<sup>2</sup>|''k''(2''k'' + 1)}}}} expresses the multiplier to turn the {{mvar|k}}th term into the {{math|(''k'' + 1)}}th term (considering {{mvar|z}} as the first term). | ||

The imaginary error function has a very similar Maclaurin series, which is: | The imaginary error function has a very similar Maclaurin series, which is: | ||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

\operatorname{erfi}(z) | |||

&= \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi}\sum_{n=0}^\infty\frac{z^{2n+1}}{n! (2n+1)} \\[6pt] | |||

&=\frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \left(z+\frac{z^3}{3}+\frac{z^5}{10}+\frac{z^7}{42}+\frac{z^9}{216}+\cdots\right) | |||

\end{align}</math> | |||

which holds for every [[Complex number|complex number]] {{mvar|z}}. | which holds for every [[Complex number|complex number]] {{mvar|z}}. | ||

===Derivative and integral=== | ===Derivative and integral=== | ||

The derivative of the error function follows immediately from its definition: | The derivative of the error function follows immediately from its definition: | ||

<math display="block">\frac{d}{dz}\operatorname{erf}(z) =\frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} e^{-z^2}.</math> | |||

From this, the derivative of the imaginary error function is also immediate: | From this, the derivative of the imaginary error function is also immediate: | ||

<math display="block">\frac{d}{dz}\operatorname{erfi}(z) =\frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} e^{z^2}.</math>Higher order derivatives are given by | |||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf}^{(k)}(z) = \frac{2 (-1)^{k-1}}{\sqrt\pi} \mathit{H}_{k-1}(z) e^{-z^2} = \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \frac{d^{k-1}}{dz^{k-1}} \left(e^{-z^2}\right),\qquad k=1, 2, \dots</math> | |||

where {{mvar|H}} are the physicists' [[Hermite polynomials]].<ref>{{mathworld|title=Erf|urlname=Erf}}</ref> | |||

An [[Antiderivative|antiderivative]] of the error function, obtainable by [[Integration by parts|integration by parts]], is | An [[Antiderivative|antiderivative]] of the error function, obtainable by [[Integration by parts|integration by parts]], is | ||

<math display="block">\int \operatorname{erf}(z) dz = z\operatorname{erf}(z) + \frac{e^{-z^2}}{\sqrt\pi}+C.</math> | |||

An antiderivative of the imaginary error function, also obtainable by integration by parts, is | An antiderivative of the imaginary error function, also obtainable by integration by parts, is | ||

<math display="block">\int \operatorname{erfi}(z) dz = z\operatorname{erfi}(z) - \frac{e^{z^2}}{\sqrt\pi}+C.</math> | |||

===Bürmann series=== | ===Bürmann series=== | ||

An expansion,<ref>{{cite journal|first1=H. M. |last1=Schöpf |first2=P. H. |last2=Supancic |title=On Bürmann's Theorem and Its Application to Problems of Linear and Nonlinear Heat Transfer and Diffusion |journal=The Mathematica Journal |year=2014 |volume=16 |doi=10.3888/tmj.16-11 |url=http://www.mathematica-journal.com/2014/11/on-burmanns-theorem-and-its-application-to-problems-of-linear-and-nonlinear-heat-transfer-and-diffusion/#more-39602/|doi-access=free }}</ref> which converges more rapidly for all real values of {{mvar|x}} than a Taylor expansion, is obtained by using Hans Heinrich Bürmann's theorem:<ref>{{mathworld|urlname=BuermannsTheorem | title = Bürmann's Theorem }}</ref> | An expansion,<ref>{{cite journal|first1=H. M. |last1=Schöpf |first2=P. H. |last2=Supancic |title=On Bürmann's Theorem and Its Application to Problems of Linear and Nonlinear Heat Transfer and Diffusion |journal=The Mathematica Journal |year=2014 |volume=16 |doi=10.3888/tmj.16-11 |url=http://www.mathematica-journal.com/2014/11/on-burmanns-theorem-and-its-application-to-problems-of-linear-and-nonlinear-heat-transfer-and-diffusion/#more-39602/|doi-access=free }}</ref> which converges more rapidly for all real values of {{mvar|x}} than a Taylor expansion, is obtained by using Hans Heinrich Bürmann's theorem:<ref>{{mathworld|urlname=BuermannsTheorem | title = Bürmann's Theorem }}</ref> | ||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

\operatorname{erf}(x) | |||

\operatorname{erf} x &= \frac 2 {\sqrt\pi} \sgn x \cdot \sqrt{1-e^{-x^2}} \left( 1-\frac{1}{12} \left (1-e^{-x^2} \right ) -\frac{7}{480} \left (1-e^{-x^2} \right )^2 -\frac{5}{896} \left (1-e^{-x^2} \right )^3-\frac{787}{276 480} \left (1-e^{-x^2} \right )^4 - \cdots \right) \\[10pt] | &= \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \sgn(x) \cdot \sqrt{1-e^{-x^2}} \left( 1-\frac{1}{12} \left (1-e^{-x^2} \right ) -\frac{7}{480} \left (1-e^{-x^2} \right )^2 -\frac{5}{896} \left (1-e^{-x^2} \right )^3-\frac{787}{276 480} \left (1-e^{-x^2} \right )^4 - \cdots \right) \\[10pt] | ||

&= \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \sgn x \cdot \sqrt{1-e^{-x^2}} \left(\frac{\sqrt\pi}{2} + \sum_{k=1}^\infty c_k e^{-kx^2} \right). | &= \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \sgn(x) \cdot \sqrt{1-e^{-x^2}} \left(\frac{\sqrt\pi}{2} + \sum_{k=1}^\infty c_k e^{-kx^2} \right). | ||

\end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

where {{math|sgn}} is the [[Sign function|sign function]]. By keeping only the first two coefficients and choosing {{math|1=''c''<sub>1</sub> = {{sfrac|31|200}}}} and {{math|1=''c''<sub>2</sub> = −{{sfrac|341|8000}}}}, the resulting approximation shows its largest [[Approximation error|relative error]] at {{math|1=''x'' = ±1.40587}}, where it is less than 0.0034361: | |||

where {{math|sgn}} is the [[Sign function|sign function]]. By keeping only the first two coefficients and choosing {{math|''c''<sub>1</sub> | <math display="block">\operatorname{erf}(x) \approx \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi}\sgn(x) \cdot \sqrt{1-e^{-x^2}} \left(\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2} + \frac{31}{200}e^{-x^2}-\frac{341}{8000} e^{-2x^2}\right). </math> | ||

===Inverse functions=== | ===Inverse functions=== | ||

[[File:Mplwp erf inv.svg|thumb|300px|Inverse error function]] | [[File:Mplwp erf inv.svg|thumb|300px|Inverse error function]] | ||

Given a complex number {{mvar|z}}, there is not a ''unique'' complex number {{mvar|w}} satisfying {{math|erf ''w'' | Given a complex number {{mvar|z}}, there is not a ''unique'' complex number {{mvar|w}} satisfying {{math|1=erf(''w'') = ''z''}}, so a true inverse function would be multivalued. However, for {{math|−1 < ''x'' < 1}}, there is a unique ''real'' number denoted {{math|erf<sup>−1</sup>(''x'')}} satisfying | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf}\left(\operatorname{erf}^{-1}(x)\right) = x.</math> | |||

The '''inverse error function''' is usually defined with domain {{open-open|−1,1}}, and it is restricted to this domain in many [[Computer algebra|computer algebra]] systems. However, it can be extended to the disk {{math|{{abs|''z''}} < 1}} of the complex plane, using the Maclaurin series<ref>{{cite arXiv | last1 = Dominici | first1 = Diego | title = Asymptotic analysis of the derivatives of the inverse error function | eprint = math/0607230 | year = 2006 }}</ref> | |||

c_k&=\sum_{m=0}^{k-1}\frac{c_m c_{k-1-m}}{(m+1)(2m+1)} \\ &= \left\{1,1,\frac{7}{6},\frac{127}{90},\frac{4369}{2520},\frac{34807}{16200},\ldots\right\}. | <math display="block">\operatorname{erf}^{-1}(z)=\sum_{k=0}^\infty\frac{c_k}{2k+1}\left (\frac{\sqrt\pi}{2}z\right )^{2k+1},</math> | ||

where {{math|1=''c''<sub>0</sub> = 1}} and | |||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

c_k & =\sum_{m=0}^{k-1}\frac{c_m c_{k-1-m}}{(m+1)(2m+1)} \\[1ex] | |||

&= \left\{1,1,\frac{7}{6},\frac{127}{90},\frac{4369}{2520},\frac{34807}{16200},\ldots\right\}. | |||

\end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

So we have the series expansion (common factors have been canceled from numerators and denominators): | So we have the series expansion (common factors have been canceled from numerators and denominators): | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf}^{-1}(z) = \frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2} \left (z + \frac{\pi}{12}z^3 + \frac{7\pi^2}{480}z^5 + \frac{127\pi^3}{40320}z^7 + \frac{4369\pi^4}{5806080} z^9 + \frac{34807\pi^5}{182476800}z^{11} + \cdots\right ).</math> | |||

(After cancellation the numerator and denominator values in {{oeis|A092676}} and {{oeis|A092677}} respectively; without cancellation the numerator terms are values in {{oeis|A002067}}.) The error function's value at {{math|±∞}} is equal to {{math|±1}}. | |||

For {{math|{{abs|''z''}} < 1}}, we have {{math|1=erf(erf<sup>−1</sup>(''z'')) = ''z''}}. | |||

For {{math|{{abs|''z''}} < 1}}, we have {{math|erf(erf<sup>−1</sup> ''z'') | |||

The '''inverse complementary error function''' is defined as | The '''inverse complementary error function''' is defined as | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erfc}^{-1}(1-z) = \operatorname{erf}^{-1}(z).</math> | |||

For real {{mvar|x}}, there is a unique ''real'' number {{math|erfi<sup>−1</sup>(''x'')}} satisfying {{math|1=erfi(erfi<sup>−1</sup>(''x'')) = ''x''}}. The '''inverse imaginary error function''' is defined as {{math|erfi<sup>−1</sup>(''x'')}}.<ref>{{cite arXiv | last1 = Bergsma | first1 = Wicher | title = On a new correlation coefficient, its orthogonal decomposition and associated tests of independence | eprint = math/0604627 | year = 2006 }}</ref> | |||

For any real ''x'', [[Newton's method]] can be used to compute {{math|erfi<sup>−1</sup>(''x'')}}, and for {{math|−1 ≤ ''x'' ≤ 1}}, the following Maclaurin series converges: | |||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erfi}^{-1}(z) =\sum_{k=0}^\infty\frac{(-1)^k c_k}{2k+1} \left( \frac{\sqrt\pi}{2} z \right)^{2k+1},</math> | |||

For any real ''x'', [[Newton's method]] can be used to compute {{math|erfi<sup>−1</sup> ''x''}}, and for {{math|−1 ≤ ''x'' ≤ 1}}, the following Maclaurin series converges: | |||

where {{math|''c''<sub>''k''</sub>}} is defined as above. | where {{math|''c''<sub>''k''</sub>}} is defined as above. | ||

===Asymptotic expansion=== | ===Asymptotic expansion=== | ||

A useful [[Asymptotic expansion|asymptotic expansion]] of the complementary error function (and therefore also of the error function) for large real {{mvar|x}} is | A useful [[Asymptotic expansion|asymptotic expansion]] of the complementary error function (and therefore also of the error function) for large real {{mvar|x}} is | ||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

\operatorname{erfc}(x) &= \frac{e^{-x^2}}{x\sqrt{\pi}}\left(1 + \sum_{n=1}^\infty (-1)^n \frac{1\cdot3\cdot5\cdots(2n - 1)}{\left(2x^2\right)^n}\right) \\[6pt] | |||

\operatorname{erfc} x &= \frac{e^{-x^2}}{x\sqrt{\pi}}\left(1 + \sum_{n=1}^\infty (-1)^n \frac{1\cdot3\cdot5\cdots(2n - 1)}{\left(2x^2\right)^n}\right) \\[6pt] | |||

&= \frac{e^{-x^2}}{x\sqrt{\pi}}\sum_{n=0}^\infty (-1)^n \frac{(2n - 1)!!}{\left(2x^2\right)^n}, | &= \frac{e^{-x^2}}{x\sqrt{\pi}}\sum_{n=0}^\infty (-1)^n \frac{(2n - 1)!!}{\left(2x^2\right)^n}, | ||

\end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

where {{math|(2''n'' − 1)!!}} is the [[Double factorial|double factorial]] of {{math|(2''n'' − 1)}}, which is the product of all odd numbers up to {{math|(2''n'' − 1)}}. This series diverges for every finite {{mvar|x}}, and its meaning as asymptotic expansion is that for any integer {{math|''N'' ≥ 1}} one has | where {{math|(2''n'' − 1)!!}} is the [[Double factorial|double factorial]] of {{math|(2''n'' − 1)}}, which is the product of all odd numbers up to {{math|(2''n'' − 1)}}. This series diverges for every finite {{mvar|x}}, and its meaning as asymptotic expansion is that for any integer {{math|''N'' ≥ 1}} one has | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erfc}(x) = \frac{e^{-x^2}}{x\sqrt{\pi}}\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} (-1)^n \frac{(2n - 1)!!}{\left(2x^2\right)^n} + R_N(x)</math> | |||

where the remainder is | where the remainder is | ||

<math display="block">R_N(x) := \frac{(-1)^N \, (2 N - 1)!!}{\sqrt{\pi} \cdot 2^{N - 1}} \int_x^\infty t^{-2N}e^{-t^2}\,\mathrm dt,</math> | |||

which follows easily by induction, writing | which follows easily by induction, writing | ||

<math display="block">e^{-t^2} = -\frac{1}{2 t} \, \frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}t} e^{-t^2}</math> | |||

and integrating by parts. | and integrating by parts. | ||

The asymptotic behavior of the remainder term, in Landau notation, is | The asymptotic behavior of the remainder term, in Landau notation, is | ||

<math display="block">R_N(x) = O\left(x^{- (1 + 2N)} e^{-x^2}\right)</math> | |||

as {{math|''x'' → ∞}}. This can be found by | as {{math|''x'' → ∞}}. This can be found by | ||

<math display="block">R_N(x) \propto \int_x^\infty t^{-2N}e^{-t^2}\,\mathrm dt = e^{-x^2} \int_0^\infty (t+x)^{-2N}e^{-t^2-2tx}\,\mathrm dt\leq e^{-x^2} \int_0^\infty x^{-2N} e^{-2tx}\,\mathrm dt \propto x^{-(1+2N)}e^{-x^2}.</math> | <math display="block">R_N(x) \propto \int_x^\infty t^{-2N}e^{-t^2}\,\mathrm dt = e^{-x^2} \int_0^\infty (t+x)^{-2N}e^{-t^2-2tx}\,\mathrm dt\leq e^{-x^2} \int_0^\infty x^{-2N} e^{-2tx}\,\mathrm dt \propto x^{-(1+2N)}e^{-x^2}.</math> | ||

For large enough values of {{mvar|x}}, only the first few terms of this asymptotic expansion are needed to obtain a good approximation of {{math|erfc ''x''}} (while for not too large values of {{mvar|x}}, the above Taylor expansion at 0 provides a very fast convergence). | For large enough values of {{mvar|x}}, only the first few terms of this asymptotic expansion are needed to obtain a good approximation of {{math|erfc ''x''}} (while for not too large values of {{mvar|x}}, the above Taylor expansion at 0 provides a very fast convergence). | ||

===Continued fraction expansion=== | ===Continued fraction expansion=== | ||

A [[Continued fraction|continued fraction]] expansion of the complementary error function | A [[Continued fraction|continued fraction]] expansion of the complementary error function was found by [[Biography:Pierre-Simon Laplace|Laplace]]:<ref>[[Biography:Pierre-Simon Laplace|Pierre-Simon Laplace]], [[Physics:Traité de mécanique céleste|Traité de mécanique céleste]], tome 4 (1805), livre X, page 255.</ref><ref>{{cite book| last1 = Cuyt | first1 = Annie A. M.| last2 = Petersen | first2 = Vigdis B. | last3 = Verdonk | first3 = Brigitte | last4 = Waadeland | first4 = Haakon | last5 = Jones | first5 = William B. | title = Handbook of Continued Fractions for Special Functions | publisher = Springer-Verlag | year = 2008 | isbn = 978-1-4020-6948-2 }}</ref> | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erfc}(z) = \frac{z}{\sqrt\pi}e^{-z^2} \cfrac{1}{z^2+ \cfrac{a_1}{1+\cfrac{a_2}{z^2+ \cfrac{a_3}{1+\dotsb}}}},\qquad a_m = \frac{m}{2}.</math> | |||

}}</ref> | |||

===Factorial series=== | ===Factorial series=== | ||

The inverse factorial series: | The inverse factorial series: | ||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

\operatorname{erfc} z &= \frac{e^{-z^2}}{\sqrt{\pi}\,z} \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n Q_n}{{(z^2+1)}^{\bar{n}}}\\ | \operatorname{erfc}(z) | ||

&= \frac{e^{-z^2}}{\sqrt{\pi}\,z} \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{\left(-1\right)^n Q_n}{{\left(z^2+1\right)}^{\bar{n}}} \\[1ex] | |||

&= \frac{e^{-z^2}}{\sqrt{\pi}\,z} \left[1 -\frac{1}{2}\frac{1}{(z^2+1)} + \frac{1}{4}\frac{1}{\left(z^2+1\right) \left(z^2+2\right)} - \cdots \right] | |||

\end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

converges for {{math|Re(''z''<sup>2</sup>) > 0}}. Here | converges for {{math|Re(''z''<sup>2</sup>) > 0}}. Here | ||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

&\overset{\text{def}}{{}={}} \frac{1}{\Gamma\left(\ | Q_n | ||

&= \sum_{k=0}^n \left(\ | &\overset{\text{def}}{{}={}} | ||

\frac{1}{\Gamma{\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)}} \int_0^\infty \tau(\tau-1)\cdots(\tau-n+1)\tau^{-\frac{1}{2}} e^{-\tau} \,d\tau \\[1ex] | |||

&= \sum_{k=0}^n \left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{\bar{k}} s(n,k), | |||

\end{align}</math> | |||

{{math|''z''<sup>{{overline|''n''}}</sup>}} denotes the rising factorial, and {{math|''s''(''n'',''k'')}} denotes a signed Stirling number of the first kind.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Schlömilch|first=Oskar Xavier | year=1859|title=Ueber facultätenreihen|url=https://archive.org/details/zeitschriftfrma09runggoog | journal=Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik | language=de | volume=4 | pages=390–415}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | last=Nielson | first=Niels | url=https://archive.org/details/handbuchgamma00nielrich | title=Handbuch der Theorie der Gammafunktion | date=1906 | publisher=B. G. Teubner | location=Leipzig|language=de|access-date=2017-12-04|at=p. 283 Eq. 3}}</ref> | {{math|''z''<sup>{{overline|''n''}}</sup>}} denotes the rising factorial, and {{math|''s''(''n'',''k'')}} denotes a signed Stirling number of the first kind.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Schlömilch|first=Oskar Xavier | year=1859|title=Ueber facultätenreihen|url=https://archive.org/details/zeitschriftfrma09runggoog | journal=Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik | language=de | volume=4 | pages=390–415}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | last=Nielson | first=Niels | url=https://archive.org/details/handbuchgamma00nielrich | title=Handbuch der Theorie der Gammafunktion | date=1906 | publisher=B. G. Teubner | location=Leipzig|language=de|access-date=2017-12-04|at=p. 283 Eq. 3}}</ref> | ||

The Taylor series can be written in terms of the [[Double factorial|double factorial]]: | |||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf}(z) = \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{(-2)^n(2n-1)!!}{(2n+1)!}z^{2n+1}</math> | |||

== Numerical approximations == | == Bounds and Numerical approximations == | ||

===Approximation with elementary functions=== | ===Approximation with elementary functions=== | ||

[[Abramowitz and Stegun]] give several approximations of varying accuracy (equations 7.1.25–28). This allows one to choose the fastest approximation suitable for a given application. In order of increasing accuracy, they are: | |||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf}(x) \approx 1 - \frac{1}{\left(1 + a_1x + a_2x^2 + a_3x^3 + a_4x^4\right)^4}, \qquad x \geq 0</math> | |||

(maximum error: {{val|5e-4}}) | (maximum error: {{val|5e-4}}) | ||

{{pb}} | {{pb}} | ||

where {{math|''a''<sub>1</sub> {{=}} 0.278393}}, {{math|''a''<sub>2</sub> {{=}} 0.230389}}, {{math|''a''<sub>3</sub> {{=}} 0.000972}}, {{math|''a''<sub>4</sub> {{=}} 0.078108}} | where {{math|''a''<sub>1</sub> {{=}} 0.278393}}, {{math|''a''<sub>2</sub> {{=}} 0.230389}}, {{math|''a''<sub>3</sub> {{=}} 0.000972}}, {{math|''a''<sub>4</sub> {{=}} 0.078108}} | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf}(x) \approx 1 - \left(a_1t + a_2t^2 + a_3t^3\right)e^{-x^2},\quad t=\frac{1}{1 + px}, \qquad x \geq 0</math> | |||

(maximum error: {{val|2.5e-5}}) | (maximum error: {{val|2.5e-5}}) | ||

{{pb}} | {{pb}} | ||

where {{math|''p'' {{=}} 0.47047}}, {{math|''a''<sub>1</sub> {{=}} 0.3480242}}, {{math|''a''<sub>2</sub> {{=}} −0.0958798}}, {{math|''a''<sub>3</sub> {{=}} 0.7478556}} | where {{math|''p'' {{=}} 0.47047}}, {{math|''a''<sub>1</sub> {{=}} 0.3480242}}, {{math|''a''<sub>2</sub> {{=}} −0.0958798}}, {{math|''a''<sub>3</sub> {{=}} 0.7478556}} | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf} x \approx 1 - \frac{1}{\left(1 + a_1x + a_2x^2 + \cdots + a_6x^6\right)^{16}}, \qquad x \geq 0</math> | <math display="block">\operatorname{erf}(x) \approx 1 - \frac{1}{\left(1 + a_1x + a_2x^2 + \cdots + a_6x^6\right)^{16}}, \qquad x \geq 0</math> | ||

(maximum error: {{val|3e-7}}) | (maximum error: {{val|3e-7}}) | ||

{{pb}} | {{pb}} | ||

where {{math|''a''<sub>1</sub> {{=}} 0.0705230784}}, {{math|''a''<sub>2</sub> {{=}} 0.0422820123}}, {{math|''a''<sub>3</sub> {{=}} 0.0092705272}}, {{math|''a''<sub>4</sub> {{=}} 0.0001520143}}, {{math|''a''<sub>5</sub> {{=}} 0.0002765672}}, {{math|''a''<sub>6</sub> {{=}} 0.0000430638}} | where {{math|''a''<sub>1</sub> {{=}} 0.0705230784}}, {{math|''a''<sub>2</sub> {{=}} 0.0422820123}}, {{math|''a''<sub>3</sub> {{=}} 0.0092705272}}, {{math|''a''<sub>4</sub> {{=}} 0.0001520143}}, {{math|''a''<sub>5</sub> {{=}} 0.0002765672}}, {{math|''a''<sub>6</sub> {{=}} 0.0000430638}} | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf} x \approx 1 - \left(a_1t + a_2t^2 + \cdots + a_5t^5\right)e^{-x^2},\quad t = \frac{1}{1 + px}</math> | <math display="block">\operatorname{erf}(x) \approx 1 - \left(a_1t + a_2t^2 + \cdots + a_5t^5\right)e^{-x^2},\quad t = \frac{1}{1 + px}</math> | ||

(maximum error: {{val|1.5e-7}}) | (maximum error: {{val|1.5e-7}}) | ||

{{pb}} | {{pb}} | ||

where {{math|''p'' {{=}} 0.3275911}}, {{math|''a''<sub>1</sub> {{=}} 0.254829592}}, {{math|''a''<sub>2</sub> {{=}} −0.284496736}}, {{math|''a''<sub>3</sub> {{=}} 1.421413741}}, {{math|''a''<sub>4</sub> {{=}} −1.453152027}}, {{math|''a''<sub>5</sub> {{=}} 1.061405429}} | where {{math|''p'' {{=}} 0.3275911}}, {{math|''a''<sub>1</sub> {{=}} 0.254829592}}, {{math|''a''<sub>2</sub> {{=}} −0.284496736}}, {{math|''a''<sub>3</sub> {{=}} 1.421413741}}, {{math|''a''<sub>4</sub> {{=}} −1.453152027}}, {{math|''a''<sub>5</sub> {{=}} 1.061405429}} | ||

{{pb}} | {{pb}} | ||

All of these approximations are valid for {{math|''x'' ≥ 0}}. To use these approximations for negative {{mvar|x}}, use the fact that {{math|erf ''x''}} is an odd function, so {{math|erf ''x'' {{=}} −erf(−''x'')}}.</ | All of these approximations are valid for {{math|''x'' ≥ 0}}. To use these approximations for negative {{mvar|x}}, use the fact that {{math|erf(''x'')}} is an odd function, so {{math|erf(''x'') {{=}} −erf(−''x'')}}. | ||

Exponential bounds and a pure exponential approximation for the complementary error function are given by<ref>{{cite journal |url = http://campus.unibo.it/85943/1/mcddmsTranWIR2003.pdf |last1= Chiani|first1= M.|last2= Dardari|first2= D. |last3=Simon |first3= M.K.|date = 2003 |title = New Exponential Bounds and Approximations for the Computation of Error Probability in Fading Channels|journal = IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications|volume = 2|number=4|pages = 840–845| doi=10.1109/TWC.2003.814350 |bibcode= 2003ITWC....2..840C| citeseerx= 10.1.1.190.6761}}</ref> | |||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

\operatorname{erfc}(x) &\leq \frac{1}{2}e^{-2 x^2} + \frac{1}{2}e^{- x^2} \leq e^{-x^2}, &\quad x &> 0 \\[1.5ex] | |||

\operatorname{erfc}(x) &\approx \frac{1}{6}e^{-x^2} + \frac{1}{2}e^{-\frac{4}{3} x^2}, &\quad x &> 0 . | |||

\end{align}</math> | |||

The above have been generalized to sums of {{mvar|N}} exponentials<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1109/TCOMM.2020.3006902 |title=Global minimax approximations and bounds for the Gaussian Q-function by sums of exponentials|journal=IEEE Transactions on Communications |year=2020 |last1=Tanash |first1=I.M. |last2=Riihonen |first2=T. |volume=68 |issue=10 |pages=6514–6524 |arxiv=2007.06939 |bibcode=2020ITCom..68.6514T |s2cid=220514754}}</ref> with increasing accuracy in terms of {{mvar|N}} so that {{math|erfc(''x'')}} can be accurately approximated or bounded by {{math|2''Q̃''({{sqrt|2}}''x'')}}, where | |||

<math display="block">\tilde{Q}(x) = \sum_{n=1}^N a_n e^{-b_n x^2}.</math> | |||

In particular, there is a systematic methodology to solve the numerical coefficients {{math|{(''a<sub>n</sub>'',''b<sub>n</sub>'')}{{su|b=''n'' {{=}} 1|p=''N''}}}} that yield a [[Minimax approximation algorithm|minimax]] approximation or bound for the closely related [[Q-function]]: {{math|''Q''(''x'') ≈ ''Q̃''(''x'')}}, {{math|''Q''(''x'') ≤ ''Q̃''(''x'')}}, or {{math|''Q''(''x'') ≥ ''Q̃''(''x'')}} for {{math|''x'' ≥ 0}}. The coefficients {{math|{(''a<sub>n</sub>'',''b<sub>n</sub>'')}{{su|b=''n'' {{=}} 1|p=''N''}}}} for many variations of the exponential approximations and bounds up to {{math|''N'' {{=}} 25}} have been released to open access as a comprehensive dataset.<ref>{{cite journal | doi=10.5281/zenodo.4112978 | title=Coefficients for Global Minimax Approximations and Bounds for the Gaussian Q-Function by Sums of Exponentials [Data set] | url=https://zenodo.org/record/4112978 | website=Zenodo | year=2020 | last1=Tanash | first1=I.M. | last2=Riihonen | first2=T.}}</ref> | |||

A tight approximation of the complementary error function for {{math|''x'' ∈ [0,∞)}} is given by Karagiannidis & Lioumpas (2007)<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Karagiannidis |first1=G. K. |last2=Lioumpas |first2=A. S. |url=http://users.auth.gr/users/9/3/028239/public_html/pdf/Q_Approxim.pdf |title=An improved approximation for the Gaussian Q-function |date=2007 |journal=IEEE Communications Letters |volume=11 |issue=8 |pages=644–646|doi=10.1109/LCOMM.2007.070470 |s2cid=4043576 }}</ref> who showed for the appropriate choice of parameters {{math|{''A'',''B''}<nowiki/>}} that | |||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erfc}(x) \approx \frac{\left(1 - e^{-Ax}\right)e^{-x^2}}{B\sqrt{\pi} x}.</math> | |||

They determined {{math|{''A'',''B''} {{=}} {1.98,1.135}<nowiki/>}}, which gave a good approximation for all {{math|''x'' ≥ 0}}. Alternative coefficients are also available for tailoring accuracy for a specific application or transforming the expression into a tight bound.<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1109/LCOMM.2021.3052257|title=Improved coefficients for the Karagiannidis–Lioumpas approximations and bounds to the Gaussian Q-function|journal=IEEE Communications Letters | year=2021 | last1=Tanash | first1=I.M.|last2=Riihonen|first2=T.|volume=25|issue=5|pages=1468–1471|arxiv=2101.07631|bibcode=2021IComL..25.1468T |s2cid=231639206}}</ref> | |||

A single-term lower bound is<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Chang |first1=Seok-Ho |last2=Cosman |first2=Pamela C. |last3=Milstein |first3=Laurence B. |date=November 2011 |title=Chernoff-Type Bounds for the Gaussian Error Function |url=http://escholarship.org/uc/item/6hw4v7pg |journal=IEEE Transactions on Communications |volume=59 |issue=11 |pages=2939–2944 |doi=10.1109/TCOMM.2011.072011.100049 |bibcode=2011ITCom..59.2939C |s2cid=13636638}}</ref> | |||

<math display="block" display="block">\operatorname{erfc}(x) \geq \sqrt{\frac{2 e}{\pi}} \frac{\sqrt{\beta - 1}}{\beta} e^{- \beta x^2}, \qquad x \ge 0,\quad \beta > 1,</math> | |||

where the parameter {{mvar|β}} can be picked to minimize error on the desired interval of approximation. | |||

Another approximation is given by Sergei Winitzki using his "global Padé approximations":<ref>{{cite book |last=Winitzki |first=Sergei |title=Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2003 |date=2003 |volume=2667 |chapter=Uniform approximations for transcendental functions |publisher=Springer, Berlin |pages=[https://archive.org/details/computationalsci0000iccs_a2w6/page/780 780–789] |isbn=978-3-540-40155-1 |doi=10.1007/3-540-44839-X_82 |chapter-url-access=registration |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/computationalsci0000iccs_a2w6 |series=Lecture Notes in Computer Science }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Zeng |first1=Caibin |last2=Chen |first2=Yang Cuan |title=Global Padé approximations of the generalized Mittag-Leffler function and its inverse |journal=Fractional Calculus and Applied Analysis |date=2015 |volume=18 |issue=6 | pages=1492–1506 |doi= 10.1515/fca-2015-0086 |quote=Indeed, Winitzki [32] provided the so-called global Padé approximation | arxiv=1310.5592 |s2cid=118148950 }}</ref>{{rp|2–3}} | |||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf}(x) \approx \sgn x \cdot \sqrt{1 - \exp\left(-x^2\frac{\frac{4}{\pi} + ax^2}{1 + ax^2}\right)}</math> | |||

where | where | ||

<math display="block">a = \frac{8(\pi - 3)}{3\pi(4 - \pi)} \approx 0.140012.</math> | |||

This is designed to be very accurate in a neighborhood of 0 and a neighborhood of infinity, and the ''relative'' error is less than 0.00035 for all real {{mvar|x}}. Using the alternate value {{math|''a'' ≈ 0.147}} reduces the maximum relative error to about 0.00013.<ref>{{Cite web <!-- Deny Citation Bot--> |url=https://www.academia.edu/9730974/A_handy_approximation_for_the_error_function_and_its_inverse |last=Winitzki |first=Sergei |date=6 February 2008 |title=A handy approximation for the error function and its inverse }}</ref> | This is designed to be very accurate in a neighborhood of 0 and a neighborhood of infinity, and the ''relative'' error is less than 0.00035 for all real {{mvar|x}}. Using the alternate value {{math|''a'' ≈ 0.147}} reduces the maximum relative error to about 0.00013.<ref>{{Cite web <!-- Deny Citation Bot--> |url=https://www.academia.edu/9730974/A_handy_approximation_for_the_error_function_and_its_inverse |last=Winitzki |first=Sergei |date=6 February 2008 |title=A handy approximation for the error function and its inverse }}</ref> | ||

{{pb}} | {{pb}} | ||

This approximation can be inverted to obtain an approximation for the inverse error function: | This approximation can be inverted to obtain an approximation for the inverse error function: | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf}^{-1}(x) \approx \sgn x \cdot \sqrt{\sqrt{\left(\frac{2}{\pi a} + \frac{\ln\left(1 - x^2\right)}{2}\right)^2 - \frac{\ln\left(1 - x^2\right)}{a}} -\left(\frac{2}{\pi a} + \frac{\ln\left(1 - x^2\right)}{2}\right)}.</math> | |||

:<math>\operatorname{erf} x = \begin{cases} | An approximation with a maximal error of {{val|1.2e-7}} for any real argument is:<ref>{{cite book | last = Press | first = William H. | title = Numerical Recipes in Fortran 77: The Art of Scientific Computing | isbn = 0-521-43064-X | year = 1992 | page = 214 | publisher = Cambridge University Press }}</ref> | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf}(x) = \begin{cases} | |||

1-\tau & x\ge 0\\ | 1-\tau & x\ge 0\\ | ||

\tau-1 & x < 0 | \tau-1 & x < 0 | ||

\end{cases}</math> | \end{cases}</math> | ||

with | with | ||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

\tau &= t\cdot\exp\left(-x^2-1.26551223+1.00002368 t+0.37409196 t^2+0.09678418 t^3 -0.18628806 t^4\right.\\ | \tau &= t\cdot\exp\left(-x^2-1.26551223+1.00002368 t+0.37409196 t^2+0.09678418 t^3 -0.18628806 t^4\right.\\ | ||

&\left. \qquad\qquad\qquad +0.27886807 t^5-1.13520398 t^6+1.48851587 t^7 -0.82215223 t^8+0.17087277 t^9\right) | &\left. \qquad\qquad\qquad +0.27886807 t^5-1.13520398 t^6+1.48851587 t^7 -0.82215223 t^8+0.17087277 t^9\right) | ||

\end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

and | and | ||

<math display="block">t = \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{2}|x|}.</math> | |||

An approximation of <math>\operatorname{erfc}</math> with a maximum relative error less than <math>2^{-53}</math> <math>\left(\approx 1.1 \times 10^{-16}\right)</math> in absolute value is:<ref>{{Cite journal | last = Dia | first = Yaya D. |date = 2023 | title = Approximate Incomplete Integrals, Application to Complementary Error Function | url = https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=4487559 | journal = SSRN Electronic Journal | language = en | doi = 10.2139/ssrn.4487559 | issn = 1556-5068}}</ref> | |||

for {{nowrap|<math>x\ge 0</math>,}} | |||

<math display="block">\begin{aligned} | |||

\operatorname{erfc} \left(x\right) | |||

\operatorname{erfc} \left(x\right) & = | & = | ||

\left(\frac{0.56418958354775629}{x+2.06955023132914151}\right) \left(\frac{x^2+2.71078540045147805 x+5.80755613130301624}{x^2+3.47954057099518960 x+12.06166887286239555}\right) \\ & \left(\frac{x^2+3.47469513777439592 x+12.07402036406381411}{x^2+3.72068443960225092 x+8.44319781003968454}\right) | \left(\frac{0.56418958354775629}{x+2.06955023132914151}\right) \left(\frac{x^2+2.71078540045147805 x+5.80755613130301624}{x^2+3.47954057099518960 x+12.06166887286239555}\right) \\ & \left(\frac{x^2+3.47469513777439592 x+12.07402036406381411}{x^2+3.72068443960225092 x+8.44319781003968454}\right) | ||

\left(\frac{x^2+4.00561509202259545 x+9.30596659485887898}{x^2+3.90225704029924078 x+6.36161630953880464}\right) \\ | \left(\frac{x^2+4.00561509202259545 x+9.30596659485887898}{x^2+3.90225704029924078 x+6.36161630953880464}\right) \\ | ||

| Line 352: | Line 302: | ||

\left(\frac{x^2+5.95908795446633271 x+9.19435612886969243}{x^2+4.11240942957450885 x+4.48640329523408675}\right) e^{-x^2} \\ | \left(\frac{x^2+5.95908795446633271 x+9.19435612886969243}{x^2+4.11240942957450885 x+4.48640329523408675}\right) e^{-x^2} \\ | ||

\end{aligned}</math> | \end{aligned}</math> | ||

and for <math>x<0</math> | |||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erfc} \left(x\right) = 2 - \operatorname{erfc} \left(-x\right)</math> | |||

A simple approximation for real-valued arguments could be done through [[Hyperbolic functions]]: | |||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf} \left(x\right) \approx z(x) = \tanh\left(\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}\left(x+\frac{11}{123}x^3\right)\right)</math> | |||

which keeps the absolute difference {{nowrap|<math>\left|\operatorname{erf} \left(x\right)-z(x)\right| < 0.000358,\, \forall x</math>.}} | |||

and | Since the error function and the Gaussian Q-function are closely related through the identity <math>\operatorname{erfc}(x) = 2 Q(\sqrt{2} x)</math> or equivalently <math>Q(x) = \frac{1}{2} \operatorname{erfc}\left(\frac{x}{\sqrt{2}}\right)</math>, bounds developed for the Q-function can be adapted to approximate the complementary error function. A pair of tight lower and upper bounds on the Gaussian Q-function for positive arguments <math>x \in [0, \infty)</math> was introduced by Abreu (2012)<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1109/TCOMM.2012.080612.110075 |title=Very Simple Tight Bounds on the Q-Function |journal=IEEE Transactions on Communications |volume=60 |issue=9 |pages=2415–2420 |year=2012 |last=Abreu |first=Giuseppe |bibcode=2012ITCom..60.2415A }}</ref> based on a simple [[Algebraic expression|algebraic expression]] with only two exponential terms: | ||

<math display="block">Q(x) \geq \frac{1}{12} e^{-x^2} + \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi} (x + 1)} e^{-x^2 / 2}, \qquad x \geq 0,</math> | |||

</ | and | ||

< | <math display="block">Q(x) \leq \frac{1}{50} e^{-x^2} + \frac{1}{2 (x + 1)} e^{-x^2 / 2}, \qquad x \geq 0.</math> | ||

These bounds stem from a unified form <math display="block">Q_{\mathrm{B}}(x; a, b) = \frac{\exp(-x^2)}{a} + \frac{\exp(-x^2 / 2)}{b (x + 1)},</math> where the parameters <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> are selected to ensure the bounding properties: for the lower bound, <math>a_{\mathrm{L}} = 12</math> and <math>b_{\mathrm{L}} = \sqrt{2\pi}</math>, and for the upper bound, <math>a_{\mathrm{U}} = 50</math> and <math>b_{\mathrm{U}} = 2</math>. | |||

These expressions maintain simplicity and tightness, providing a practical trade-off between accuracy and ease of computation. They are particularly valuable in theoretical contexts, such as communication theory over fading channels, where both functions frequently appear. Additionally, the original Q-function bounds can be extended to <math>Q^n(x)</math> for positive integers <math>n</math> via the [[Binomial theorem|binomial theorem]], suggesting potential adaptability for powers of <math>\operatorname{erfc}(x)</math>, though this is less commonly required in error function applications. | |||

===Table of values=== | ===Table of values=== | ||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:left;margin-left:24pt" | {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:left;margin-left:24pt" | ||

! {{math|''x''}}!! {{math|erf(''x'')}} !! {{math|1 − erf(''x'')}} | |||

! {{math|''x''}}!! {{math|erf ''x''}} !! {{math|1 − erf ''x''}} | |||

|- | |- | ||

|0 || {{val|0}} || {{val|1}} | |0 || {{val|0}} || {{val|1}} | ||

| Line 433: | Line 387: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|3.5 || {{val|0.999999257}} || {{val|0.000000743}} | |3.5 || {{val|0.999999257}} || {{val|0.000000743}} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 440: | Line 393: | ||

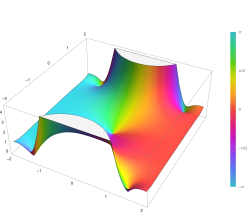

===Complementary error function=== | ===Complementary error function=== | ||

The '''complementary error function''', denoted {{math|erfc}}, is defined as | The '''complementary error function''', denoted {{math|erfc}}, is defined as | ||

[[File:Plot of the complementary error function Erfc(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D.svg|alt=Plot of the complementary error function erfc(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D|thumb|Plot of the complementary error function erfc(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D]] | |||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

\operatorname{erfc} x | \operatorname{erfc}(x) | ||

& = 1-\operatorname{erf} x \\[5pt] | & = 1-\operatorname{erf}(x) \\[5pt] | ||

& = \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \int_x^\infty e^{-t^2}\, | & = \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \int_x^\infty e^{-t^2}\,dt \\[5pt] | ||

& = e^{-x^2} \operatorname{erfcx} x, | & = e^{-x^2} \operatorname{erfcx}(x), | ||

\end{align} </math> | \end{align} </math> | ||

which also defines {{math|erfcx}}, the '''scaled complementary error function'''<ref name=Cody93>{{Citation |first=W. J. |last=Cody |title=Algorithm 715: SPECFUN—A portable FORTRAN package of special function routines and test drivers |url=http://www.stat.wisc.edu/courses/st771-newton/papers/p22-cody.pdf |journal=ACM Trans. Math. Softw. |volume=19 |issue=1 |pages=22–32 |date=March 1993 |doi=10.1145/151271.151273|citeseerx=10.1.1.643.4394 |s2cid=5621105 }}</ref> (which can be used instead of {{math|erfc}} to avoid [[Arithmetic underflow|arithmetic underflow]]<ref name=Cody93/><ref name=Zaghloul07>{{Citation |first=M. R. |last=Zaghloul |title=On the calculation of the Voigt line profile: a single proper integral with a damped sine integrand | journal = [[Organization:Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society|Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society]] |volume=375 |issue=3 |pages=1043–1048 |date=1 March 2007 |doi=10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.11377.x|bibcode=2007MNRAS.375.1043Z |doi-access=free }}</ref>). Another form of {{math|erfc ''x''}} for {{math|''x'' ≥ 0}} is known as Craig's formula, after its discoverer:<ref>John W. Craig, [http://wsl.stanford.edu/~ee359/craig.pdf ''A new, simple and exact result for calculating the probability of error for two-dimensional signal constellations''] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120403231129/http://wsl.stanford.edu/~ee359/craig.pdf |date=3 April 2012 }}, Proceedings of the 1991 IEEE Military Communication Conference, vol. 2, pp. 571–575.</ref> | |||

which also defines {{math|erfcx}}, the '''scaled complementary error function'''<ref name=Cody93>{{Citation |first=W. J. |last=Cody |title=Algorithm 715: SPECFUN—A portable FORTRAN package of special function routines and test drivers |url=http://www.stat.wisc.edu/courses/st771-newton/papers/p22-cody.pdf |journal=ACM Trans. Math. Softw. |volume=19 |issue=1 |pages=22–32 |date=March 1993 |doi=10.1145/151271.151273|citeseerx=10.1.1.643.4394 |s2cid=5621105 }}</ref> (which can be used instead of {{math|erfc}} to avoid [[Arithmetic underflow|arithmetic underflow]]<ref name=Cody93/><ref name=Zaghloul07>{{Citation |first=M. R. |last=Zaghloul |title=On the calculation of the Voigt line profile: a single proper integral with a damped sine integrand |journal=[[Organization:Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society|Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society]] |volume=375 |issue=3 |pages=1043–1048 |date=1 March 2007 |doi=10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.11377.x|bibcode=2007MNRAS.375.1043Z |doi-access=free }}</ref>). Another form of {{math|erfc ''x''}} for {{math|''x'' ≥ 0}} is known as Craig's formula, after its discoverer:<ref>John W. Craig, [http://wsl.stanford.edu/~ee359/craig.pdf ''A new, simple and exact result for calculating the probability of error for two-dimensional signal constellations''] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120403231129/http://wsl.stanford.edu/~ee359/craig.pdf |date=3 April 2012 }}, Proceedings of the 1991 IEEE Military Communication Conference, vol. 2, pp. 571–575.</ref> | <math display="block">\operatorname{erfc} (x \mid x\ge 0) | ||

= \frac{2}{\pi} \int_0^\frac{\pi}{2} \exp \left( - \frac{x^2}{\sin^2 \theta} \right) \, d\theta.</math> | |||

= \frac 2 \pi \int_0^\frac{\pi}{2} \exp \left( - \frac{x^2}{\sin^2 \theta} \right) \, | This expression is valid only for positive values of {{mvar|x}}, but it can be used in conjunction with {{math|erfc(''x'') {{=}} 2 − erfc(−''x'')}} to obtain {{math|erfc(''x'')}} for negative values. This form is advantageous in that the range of integration is fixed and finite. An extension of this expression for the {{math|erfc}} of the sum of two non-negative variables is as follows:<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1109/TCOMM.2020.2986209 |title=A Novel Extension to Craig's Q-Function Formula and Its Application in Dual-Branch EGC Performance Analysis|journal=IEEE Transactions on Communications |volume=68 |issue=7 |pages=4117–4125 |year=2020 |last1=Behnad |first1=Aydin |bibcode=2020ITCom..68.4117B |s2cid=216500014}}</ref> | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erfc} (x+y \mid x,y\ge 0) = \frac{2}{\pi} \int_0^\frac{\pi}{2} \exp \left( - \frac{x^2}{\sin^2 \theta} - \frac{y^2}{\cos^2 \theta} \right) \,\mathrm d\theta.</math> | |||

This expression is valid only for positive values of {{mvar|x}}, but it can be used in conjunction with {{math|erfc ''x'' {{=}} 2 − erfc(−''x'')}} to obtain {{math|erfc(''x'')}} for negative values. This form is advantageous in that the range of integration is fixed and finite. An extension of this expression for the {{math|erfc}} of the sum of two non-negative variables is as follows:<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1109/TCOMM.2020.2986209 |title=A Novel Extension to Craig's Q-Function Formula and Its Application in Dual-Branch EGC Performance Analysis|journal=IEEE Transactions on Communications |volume=68 |issue=7 |pages=4117–4125 |year=2020 |last1=Behnad |first1=Aydin |s2cid=216500014}}</ref> | |||

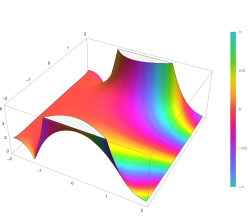

===Imaginary error function=== | ===Imaginary error function=== | ||

The '''imaginary error function''', denoted {{math|erfi}}, is defined as | The '''imaginary error function''', denoted {{math|erfi}}, is defined as | ||

[[File:Plot of the imaginary error function Erfi(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D.svg|alt=Plot of the imaginary error function | [[File:Plot of the imaginary error function Erfi(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D.svg|alt=Plot of the imaginary error function erfi(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D|thumb|Plot of the imaginary error function erfi(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D]] | ||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

\operatorname{erfi} x | \operatorname{erfi}(x) | ||

& = -i\operatorname{erf} ix \\[5pt] | & = -i\operatorname{erf}(ix) \\[5pt] | ||

& = \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \int_0^x e^{t^2}\, | & = \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} \int_0^x e^{t^2}\,dt \\[5pt] | ||

& = \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} e^{x^2} D(x), | & = \frac{2}{\sqrt\pi} e^{x^2} D(x), | ||

\end{align} </math> | \end{align} </math> | ||

where {{math|''D''(''x'')}} is the [[Dawson function]] (which can be used instead of {{math|erfi}} to avoid [[Arithmetic overflow|arithmetic overflow]]<ref name=Cody93/>). | where {{math|''D''(''x'')}} is the [[Dawson function]] (which can be used instead of {{math|erfi}} to avoid [[Arithmetic overflow|arithmetic overflow]]<ref name=Cody93/>). | ||

Despite the name "imaginary error function", {{math|erfi ''x''}} is real when {{mvar|x}} is real. | Despite the name "imaginary error function", {{math|erfi(''x'')}} is real when {{mvar|x}} is real. | ||

When the error function is evaluated for arbitrary [[Complex number|complex]] arguments {{mvar|z}}, the resulting '''complex error function''' is usually discussed in scaled form as the [[Faddeeva function]]: | When the error function is evaluated for arbitrary [[Complex number|complex]] arguments {{mvar|z}}, the resulting '''complex error function''' is usually discussed in scaled form as the [[Faddeeva function]]: | ||

<math display="block">w(z) = e^{-z^2}\operatorname{erfc}(-iz) = \operatorname{erfcx}(-iz).</math> | |||

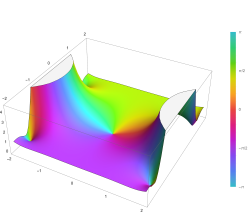

===Cumulative distribution function=== | ===Cumulative distribution function=== | ||

The error function is essentially identical to the standard normal cumulative distribution function, denoted {{math|Φ}}, also named {{math|norm(''x'')}} by some software languages | The error function is essentially identical to the standard normal cumulative distribution function, denoted {{math|Φ}}, also named {{math|norm(''x'')}} by some software languages , as they differ only by scaling and translation. Indeed, | ||

[[File:Normal cumulative distribution function complex plot in Mathematica 13.1 with ComplexPlot3D.svg|alt=the normal cumulative distribution function plotted in the complex plane|thumb|the normal cumulative distribution function plotted in the complex plane]] | |||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

&=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}\int_{-\infty}^x e^\tfrac{-t^2}{2}\, | \Phi(x) | ||

&= \ | &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^x e^\tfrac{-t^2}{2}\,dt\\[6pt] | ||

&=\ | &= \frac{1}{2} \left(1+\operatorname{erf}\left(\frac{x}{\sqrt 2}\right)\right)\\[6pt] | ||

&= \frac{1}{2} \operatorname{erfc}\left(-\frac{x}{\sqrt 2}\right) | |||

\end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

or rearranged for {{math|erf}} and {{math|erfc}}: | or rearranged for {{math|erf}} and {{math|erfc}}: | ||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

\operatorname{erf}(x) &= 2 \Phi{\left ( x \sqrt{2} \right )} - 1 \\[6pt] | |||

\operatorname{erf}(x) &= 2 \Phi \left ( x \sqrt{2} \right ) - 1 \\[6pt] | \operatorname{erfc}(x) &= 2 \Phi{\left ( - x \sqrt{2} \right )} \\ | ||

\operatorname{erfc}(x) &= 2 \Phi \left ( - x \sqrt{2} \right ) \\ &=2\left(1-\Phi \left ( x \sqrt{2} \right)\right). | &= 2\left(1 - \Phi{\left ( x \sqrt{2} \right)}\right). | ||

\end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

Consequently, the error function is also closely related to the [[Q-function]], which is the tail probability of the standard normal distribution. The Q-function can be expressed in terms of the error function as | Consequently, the error function is also closely related to the [[Q-function]], which is the tail probability of the standard normal distribution. The Q-function can be expressed in terms of the error function as | ||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

Q(x) &= \frac{1}{2} - \frac{1}{2} \operatorname{erf}\left(\frac{x}{\sqrt 2}\right)\\ | |||

Q(x) &=\ | &= \frac{1}{2}\operatorname{erfc}\left(\frac{x}{\sqrt 2}\right). | ||

&=\ | |||

\end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

The [[Inverse function|inverse]] of {{math|Φ}} is known as the [[Quantile function|normal quantile function]], or [[Probit|probit]] function and may be expressed in terms of the inverse error function as | The [[Inverse function|inverse]] of {{math|Φ}} is known as the [[Quantile function|normal quantile function]], or [[Probit|probit]] function and may be expressed in terms of the inverse error function as | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{probit}(p) = \Phi^{-1}(p) = \sqrt{2}\operatorname{erf}^{-1}(2p-1) = -\sqrt{2}\operatorname{erfc}^{-1}(2p).</math> | |||

The standard normal cdf is used more often in probability and statistics, and the error function is used more often in other branches of mathematics. | The standard normal cdf is used more often in probability and statistics, and the error function is used more often in other branches of mathematics. | ||

The error function is a special case of the [[Mittag-Leffler function]], and can also be expressed as a [[Confluent hypergeometric function|confluent hypergeometric function]] (Kummer's function): | The error function is a special case of the [[Mittag-Leffler function]], and can also be expressed as a [[Confluent hypergeometric function|confluent hypergeometric function]] (Kummer's function): | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf}(x) = \frac{2x}{\sqrt\pi} M\left(\tfrac{1}{2},\tfrac{3}{2},-x^2\right).</math> | |||

It has a simple expression in terms of the [[Fresnel integral]].{{Elucidate|date=May 2012}} | It has a simple expression in terms of the [[Fresnel integral]].{{Elucidate|date=May 2012}} | ||

In terms of the regularized gamma function {{mvar|P}} and the [[Incomplete gamma function|incomplete gamma function]], | In terms of the regularized gamma function {{mvar|P}} and the [[Incomplete gamma function|incomplete gamma function]], | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{erf}(x) | |||

= \sgn(x) \cdot P\left(\tfrac{1}{2}, x^2\right) | |||

= \frac{\sgn(x)}{\sqrt\pi} \gamma{\left(\tfrac{1}{2}, x^2\right)}.</math>{{math|sgn(''x'')}} is the [[Sign function|sign function]]. | |||

</math> | |||

===Iterated integrals of the complementary error function=== | ===Iterated integrals of the complementary error function=== | ||

The iterated integrals of the complementary error function are defined by<ref>{{ | The iterated integrals of the complementary error function are defined by<ref>{{cite book | last1 = Carslaw | first1 = H. S. | last2 = Jaeger | first2 = J. C.| year = 1959 | title = Conduction of Heat in Solids | edition = 2nd | publisher = Oxford University Press | isbn = 978-0-19-853368-9 | page = 484}}</ref> | ||

<math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

i^n\!\operatorname{erfc}(z) &= \int_z^\infty i^{n-1}\!\operatorname{erfc}(\zeta)\,d\zeta \\[6pt] | |||

i^0\!\operatorname{erfc}(z) &= \operatorname{erfc}(z) \\ | |||

i^1\!\operatorname{erfc}(z) &= \operatorname{ierfc}(z) = \frac{1}{\sqrt\pi} e^{-z^2} - z \operatorname{erfc}(z) \\ | |||

i^2\!\operatorname{erfc}(z) &= \tfrac{1}{4} \left( \operatorname{erfc}(z) -2 z \operatorname{ierfc}(z) \right) \\ | |||

\end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

The general recurrence formula is | The general recurrence formula is | ||

<math display="block">2 n \cdot i^n\!\operatorname{erfc}(z) = i^{n-2}\!\operatorname{erfc}(z) -2 z \cdot i^{n-1}\!\operatorname{erfc}(z)</math> | |||

They have the power series | They have the power series | ||

<math display="block">i^n\!\operatorname{erfc}(z) =\sum_{j=0}^\infty \frac{(-z)^j}{2^{n-j}j! \,\Gamma \left( 1 + \frac{n-j}{2}\right)},</math> | |||

from which follow the symmetry properties | from which follow the symmetry properties | ||

<math display="block">i^{2m}\!\operatorname{erfc}(-z) =-i^{2m}\!\operatorname{erfc}(z) +\sum_{q=0}^m \frac{z^{2q}}{2^{2(m-q)-1}(2q)! (m-q)!}</math> | |||

and | and | ||

<math display="block">i^{2m+1}\!\operatorname{erfc}(-z) =i^{2m+1}\!\operatorname{erfc}(z) +\sum_{q=0}^m \frac{z^{2q+1}}{2^{2(m-q)-1}(2q+1)! (m-q)!}. | |||

</math> | </math> | ||

| Line 572: | Line 481: | ||

===As real function of a real argument=== | ===As real function of a real argument=== | ||

* In [[POSIX]]-compliant operating systems, the header <code>math.h</code> shall declare and the mathematical library <code>libm</code> shall provide the functions <code>erf</code> and <code>erfc</code> (double precision) as well as their single precision and [[Extended precision|extended precision]] counterparts <code>erff</code>, <code>erfl</code> and <code>erfcf</code>, <code>erfcl</code>.<ref>{{cite web | * In [[POSIX]]-compliant operating systems, the header <code>math.h</code> shall declare and the mathematical library <code>libm</code> shall provide the functions <code>erf</code> and <code>erfc</code> (double precision) as well as their single precision and [[Extended precision|extended precision]] counterparts <code>erff</code>, <code>erfl</code> and <code>erfcf</code>, <code>erfcl</code>.<ref>{{cite web | url = https://pubs.opengroup.org/onlinepubs/9699919799/basedefs/math.h.html | access-date = 21 April 2023 | website = opengroup.org | title = math.h - mathematical declarations | year = 2018 | issue = 7}}</ref> | ||

|url=https://pubs.opengroup.org/onlinepubs/9699919799/basedefs/math.h.html|access-date=21 April 2023|website=opengroup.org|title=math.h - mathematical declarations|year=2018|issue=7}}</ref> | |||

* The [[Software:GNU Scientific Library|GNU Scientific Library]] provides <code>erf</code>, <code>erfc</code>, <code>log(erf)</code>, and scaled error functions.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.gnu.org/software/gsl/doc/html/specfunc.html#error-functions|title = Special Functions – GSL 2.7 documentation}}</ref> | * The [[Software:GNU Scientific Library|GNU Scientific Library]] provides <code>erf</code>, <code>erfc</code>, <code>log(erf)</code>, and scaled error functions.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.gnu.org/software/gsl/doc/html/specfunc.html#error-functions|title = Special Functions – GSL 2.7 documentation}}</ref> | ||

| Line 580: | Line 487: | ||

* <code>[https://jugit.fz-juelich.de/mlz/libcerf libcerf]</code>, numeric C library for complex error functions, provides the complex functions <code>cerf</code>, <code>cerfc</code>, <code>cerfcx</code> and the real functions <code>erfi</code>, <code>erfcx</code> with approximately 13–14 digits precision, based on the [[Faddeeva function]] as implemented in the [http://ab-initio.mit.edu/Faddeeva MIT Faddeeva Package] | * <code>[https://jugit.fz-juelich.de/mlz/libcerf libcerf]</code>, numeric C library for complex error functions, provides the complex functions <code>cerf</code>, <code>cerfc</code>, <code>cerfcx</code> and the real functions <code>erfi</code>, <code>erfcx</code> with approximately 13–14 digits precision, based on the [[Faddeeva function]] as implemented in the [http://ab-initio.mit.edu/Faddeeva MIT Faddeeva Package] | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 601: | Line 493: | ||

==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

* {{AS ref |7|297}} | * {{AS ref |7|297}} | ||

*{{Citation |last1=Press |first1=William H. |last2=Teukolsky |first2=Saul A. |last3=Vetterling |first3=William T. |last4=Flannery |first4=Brian P. |year=2007 |title=Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing |edition=3rd |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=New York |isbn=978-0-521-88068-8 |chapter=Section 6.2. Incomplete Gamma Function and Error Function |chapter-url=http://apps.nrbook.com/empanel/index.html#pg=259 }} | *{{Citation |last1=Press |first1=William H. |last2=Teukolsky |first2=Saul A. |last3=Vetterling |first3=William T. |last4=Flannery |first4=Brian P. |year=2007 |title=Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing |edition=3rd |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=New York |isbn=978-0-521-88068-8 |chapter=Section 6.2. Incomplete Gamma Function and Error Function |chapter-url=http://apps.nrbook.com/empanel/index.html#pg=259 |access-date=9 August 2011 |archive-date=11 August 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110811154417/http://apps.nrbook.com/empanel/index.html#pg=259 |url-status=dead }} | ||

*{{dlmf|id=7|title=Error Functions, Dawson’s and Fresnel Integrals|first=Nico M. |last=Temme }} | *{{dlmf|id=7|title=Error Functions, Dawson’s and Fresnel Integrals|first=Nico M. |last=Temme }} | ||

| Line 607: | Line 499: | ||

* [http://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/jres/73B/jresv73Bn1p1_A1b.pdf A Table of Integrals of the Error Functions] | * [http://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/jres/73B/jresv73Bn1p1_A1b.pdf A Table of Integrals of the Error Functions] | ||

{{Nonelementary Integral}} | |||

[[Category:Special hypergeometric functions]] | [[Category:Special hypergeometric functions]] | ||

Latest revision as of 09:35, 12 February 2026

In mathematics, the error function (also called the Gauss error function), often denoted by erf, is a function defined as:[1] Template:Infobox mathematical function

The integral here is a complex contour integral which is path-independent because is holomorphic on the whole complex plane . In many applications, the function argument is a real number, in which case the function value is also real.

In some old texts,[2] the error function is defined without the factor of . This nonelementary integral is a sigmoid function that occurs often in probability, statistics, and partial differential equations.

In statistics, for non-negative real values of x, the error function has the following interpretation: for a real random variable Y that is normally distributed with mean 0 and standard deviation , erf(x) is the probability that Y falls in the range [−x, x].

Two closely related functions are the complementary error function is defined as

and the imaginary error function is defined as

where i is the imaginary unit.

Name

The name "error function" and its abbreviation erf were proposed by J. W. L. Glaisher in 1871 on account of its connection with "the theory of Probability, and notably the theory of Errors."[3] The error function complement was also discussed by Glaisher in a separate publication in the same year.[4] For the "law of facility" of errors whose density is given by (the normal distribution), Glaisher calculates the probability of an error lying between p and q as:

Applications

When the results of a series of measurements are described by a normal distribution with standard deviation σ and expected value 0, then erf (a/σ √2) is the probability that the error of a single measurement lies between −a and +a, for positive a. This is useful, for example, in determining the bit error rate of a digital communication system.

The error and complementary error functions occur, for example, in solutions of the heat equation when boundary conditions are given by the Heaviside step function.

The error function and its approximations can be used to estimate results that hold with high probability or with low probability. Given a random variable X ~ Norm[μ,σ] (a normal distribution with mean μ and standard deviation σ) and a constant L > μ, it can be shown via integration by substitution:

where A and B are certain numeric constants. If L is sufficiently far from the mean, specifically μ − L ≥ σ√ln(k), then:

so the probability goes to 0 as k → ∞.

The probability for X being in the interval [La, Lb] can be derived as

Properties

The property erf (−z) = −erf(z) means that the error function is an odd function. This directly results from the fact that the integrand e−t2 is an even function (the antiderivative of an even function which is zero at the origin is an odd function and vice versa).

Since the error function is an entire function which takes real numbers to real numbers, for any complex number z: where denotes the complex conjugate of .

The integrand f = exp(−z2) and f = erf(z) are shown in the complex z-plane in the figures at right with domain coloring.

The error function at +∞ is exactly 1 (see Gaussian integral). At the real axis, erf z approaches unity at z → +∞ and −1 at z → −∞. At the imaginary axis, it tends to ±i∞.

Taylor series

The error function is an entire function; it has no singularities (except that at infinity) and its Taylor expansion always converges. For x >> 1, however, cancellation of leading terms makes the Taylor expansion unpractical.

The defining integral cannot be evaluated in closed form in terms of elementary functions (see Liouville's theorem), but by expanding the integrand e−z2 into its Maclaurin series and integrating term by term, one obtains the error function's Maclaurin series as: which holds for every complex number z. The denominator terms are sequence A007680 in the OEIS.

It is a special case of Kummer's function:

For iterative calculation of the above series, the following alternative formulation may be useful: because −(2k − 1)z2/k(2k + 1) expresses the multiplier to turn the kth term into the (k + 1)th term (considering z as the first term).

The imaginary error function has a very similar Maclaurin series, which is: which holds for every complex number z.

Derivative and integral

The derivative of the error function follows immediately from its definition: From this, the derivative of the imaginary error function is also immediate: Higher order derivatives are given by where H are the physicists' Hermite polynomials.[5]

An antiderivative of the error function, obtainable by integration by parts, is An antiderivative of the imaginary error function, also obtainable by integration by parts, is

Bürmann series

An expansion,[6] which converges more rapidly for all real values of x than a Taylor expansion, is obtained by using Hans Heinrich Bürmann's theorem:[7] where sgn is the sign function. By keeping only the first two coefficients and choosing c1 = 31/200 and c2 = −341/8000, the resulting approximation shows its largest relative error at x = ±1.40587, where it is less than 0.0034361:

Inverse functions

Given a complex number z, there is not a unique complex number w satisfying erf(w) = z, so a true inverse function would be multivalued. However, for −1 < x < 1, there is a unique real number denoted erf−1(x) satisfying

The inverse error function is usually defined with domain (−1,1), and it is restricted to this domain in many computer algebra systems. However, it can be extended to the disk |z| < 1 of the complex plane, using the Maclaurin series[8] where c0 = 1 and

So we have the series expansion (common factors have been canceled from numerators and denominators): (After cancellation the numerator and denominator values in OEIS: A092676 and OEIS: A092677 respectively; without cancellation the numerator terms are values in OEIS: A002067.) The error function's value at ±∞ is equal to ±1.

For |z| < 1, we have erf(erf−1(z)) = z.

The inverse complementary error function is defined as For real x, there is a unique real number erfi−1(x) satisfying erfi(erfi−1(x)) = x. The inverse imaginary error function is defined as erfi−1(x).[9]

For any real x, Newton's method can be used to compute erfi−1(x), and for −1 ≤ x ≤ 1, the following Maclaurin series converges: where ck is defined as above.

Asymptotic expansion

A useful asymptotic expansion of the complementary error function (and therefore also of the error function) for large real x is where (2n − 1)!! is the double factorial of (2n − 1), which is the product of all odd numbers up to (2n − 1). This series diverges for every finite x, and its meaning as asymptotic expansion is that for any integer N ≥ 1 one has where the remainder is which follows easily by induction, writing and integrating by parts.