Physics:Vector model of the atom

| Part of a series on |

| Quantum mechanics |

|---|

| [math]\displaystyle{ i \hbar \frac{\partial}{\partial t} | \psi (t) \rangle = \hat{H} | \psi (t) \rangle }[/math] |

This article needs attention from an expert on the subject. (April 2011) |

In physics, specifically quantum mechanics, the vector model of the atom is a model of the atom in terms of angular momentum.[1] It can be considered as the extension of the Rutherford-Bohr-Sommerfeld atom model to multi-electron atoms.

Introduction

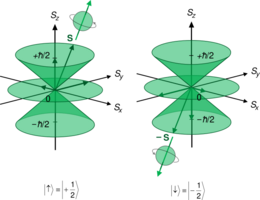

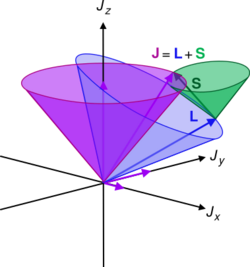

The model is a convenient representation of the angular momenta of the electrons in the atom. Angular momentum is always split into orbital L, spin S and total J:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{J}=\mathbf{L}+\mathbf{S}. }[/math]

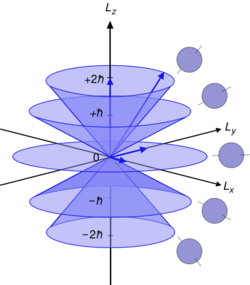

Given that in quantum mechanics, angular momentum is quantized and there is an uncertainty relation for the components of each vector, the representation turns out to be quite simple (although the background mathematics is quite complex). Geometrically it is a discrete set of right-circular cones, without the circular base, in which the axes of all the cones are lined up onto a common axis, conventionally the z-axis for three-dimensional Cartesian coordinates.[2] Following is the background to this construction.

Mathematical background of angular momenta

The commutator implies that for each of L, S, and J, only one component of any angular momentum vector can be measured at any instant of time; at the same the other two are indeterminate. The commutator of any two angular momentum operators (corresponding to component directions) is non-zero. Following is a summary of the relevant mathematics in constructing the vector model.

The commutation relations are (using the Einstein summation convention):

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & [\hat{L}_a, \hat{L}_b ] = i \hbar \varepsilon_{abc} \hat{L}_c \\ & [\hat{S}_a, \hat{S}_b ] = i \hbar \varepsilon_{abc} \hat{S}_c \\ \end{align} }[/math]

where

- L = (L1, L2, L3), S = (S1, S2, S3) and J = (J1, J2, J3) (these correspond to L = (Lx, Ly, Lz), S = (Sx, Sy, Sz) and J = (Jx, Jy, Jz) in Cartesian coordinates),

- a, b, c ∊ {1,2,3} are indices labelling the components of angular momenta

- εabc is the 3-index permutation tensor in 3-d.

The magnitudes of L, S and J however can be measured at the same time, since the commutation of the square of an angular momentum operator (full resultant, not components) with any one component is zero, so simultaneous measurement of [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{L}_a }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{L}^2 }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{S}_a }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{S}^2 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{J}_a }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{J}^2 }[/math] satisfy:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & [\hat{L}_a, \hat{L}^2] = 0\\ & [\hat{S}_a, \hat{S}^2] = 0\\ & [\hat{J}_a, \hat{J}^2] = 0\\ \end{align} }[/math]

The magnitudes satisfy all of the following, in terms of operators and vector components:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \hat{L}^2 = \hat{L}_x^2 + \hat{L}_y^2 +\hat{L}_z^2 \,\, \rightleftharpoons \,\, \mathbf{L}\cdot\mathbf{L}= L^2 = L_x^2 + L_y^2 + L_z^2,\\ & \hat{S}^2 = \hat{S}_x^2 + \hat{S}_y^2 +\hat{S}_z^2 \,\, \rightleftharpoons \,\, \mathbf{S}\cdot\mathbf{S}= S^2 = S_x^2 + S_y^2 + S_z^2,\\ & \hat{J}^2 = \hat{J}_x^2 + \hat{J}_y^2 +\hat{J}_z^2 \,\, \rightleftharpoons \,\, \mathbf{J}\cdot\mathbf{J}= J^2 = J_x^2 + J_y^2 + J_z^2,\\ \end{align} }[/math]

and quantum numbers:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & |\mathbf{L}| = \hbar \sqrt{\ell(\ell+1)}, \quad L_z = m_\ell \hbar, \\ & |\mathbf{S}| = \hbar \sqrt{s(s+1)}, \quad S_z = m_s \hbar, \\ & |\mathbf{J}| = \hbar \sqrt{j(j+1)}, \quad J_z = m_j \hbar, \\ \end{align} }[/math]

where

- [math]\displaystyle{ \scriptstyle \ell }[/math], is the azimuthal quantum number,

- s, is the spin quantum number intrinsic to the type of particle,

- j, is the total angular momentum quantum number,

which respectively take the values:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & m_\ell \in \{ -\ell, -(\ell-1) \cdots \ell-1, \ell \} , \quad \ell \in \{ 0,1 \cdots n-1 \} \\ & m_s \in \{ -s, -(s-1) \cdots s-1, s \} , \\ & m_j \in \{ -j, -(j-1) \cdots j-1, j \} , \\ & m_j=m_\ell+m_s, \quad j=|\ell+s|\\ \end{align} }[/math]

These mathematical facts suggest the continuum of all possible angular momenta for a corresponding specified quantum number:

- One direction is constant, the other two are variable.

- The magnitude of the vectors must be constant (for a specified state corresponding to the quantum number), so the two indeterminate components of each of the vectors must be confined to a circle, in such a way that the measurable and un-measurable components (at an instant of time) allow the magnitudes to be constructed correctly, for all possible indeterminate components.

The geometrical result is a cone of vectors, the vector starts at the apex of the cone and its tip reaches the circumference of the cone. It is convention to use the z-component for the measurable component of angular momentum, so the axis of the cone must be the z-axis, directed from the apex to the plane defined by the circular base of the cone, perpendicular to the plane. For different quantum numbers, the cones are different. So there are a discrete number of states the angular momenta can be, ruled by the above possible values for [math]\displaystyle{ \scriptstyle \ell }[/math], s, and j. Using the previous set-up of the vector as part of a cone, each state must correspond to a cone. This is for increasing [math]\displaystyle{ \scriptstyle \ell }[/math], s, and j, and decreasing [math]\displaystyle{ \scriptstyle \ell }[/math], s, and j> Negative quantum numbers correspond to cones reflected in the x-y plane. One of these states, for a quantum number equal to zero, clearly doesn't correspond to a cone, only a circle in the x-y plane.

The number of cones (including the degenerate planar circle) equals the multiplicity of states, [math]\displaystyle{ \scriptstyle 2\ell+1 }[/math].

Bohr model

It can be considered the extension of the Bohr model because Niels Bohr also proposed angular momentum was quantized according to:

- [math]\displaystyle{ L = m\hbar }[/math]

where m is an integer, produced correct results for the Hydrogen atom. Although the Bohr model doesn't apply to multi-electron atoms, it was the first successful quantization of angular momentum applied to the atom, preceding the vector model of the atom.

Addition of angular momenta

For one-electron atoms (i.e. hydrogen), there is only one set of cones for the orbiting electron. For multi-electron atoms, there are many states, due to the increasing number of electrons.

The angular momenta of all electrons in the atom add vectorially. Most atomic processes, both nuclear and chemical (electronic) – except in the absolutely stochastic process of radioactive decay - are determined by spin-pairing and coupling of angular momenta due to neighbouring nucleons and electrons. The term "coupling" in this context means the vector superposition of angular momenta, that is, magnitudes and directions are added.

In multi-electron atoms, the vector sum of two angular momenta is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{J} = \mathbf{J}_1 + \mathbf{J}_2 \,\! }[/math]

for the z-component, the projected values are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ J_z = J_{1z} + J_{2z} \,\! }[/math]

where

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \mathbf{J}_z = m_j \hbar \\ & \mathbf{J}_{1z} = m_{j_1} \hbar \\ & \mathbf{J}_{2z} = m_{j_2} \hbar \\ \end{align} \,\! }[/math]

and the magnitudes are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & |\mathbf{J}| = \hbar\sqrt{j(j+1)} \\ & |\mathbf{J}_1| = \hbar\sqrt{j_1(j_1+1)} \\ & |\mathbf{J}_2| = \hbar\sqrt{j_2(j_2+1)} \\ \end{align} }[/math]

in which

- [math]\displaystyle{ j \in \{ |j_1 - j_2|, |j_1 - j_2| - 1 \cdots j_1 + j_2 - 1, j_1 + j_2 \} \,\! }[/math]

This process may be repeated for a third electron, then the fourth etc. until the total angular momentum has been found.

LS coupling

The process of adding all angular momenta together is a laborious task, since the resultant momenta is not definite, the entire cones of precessing momenta about the z-axis must be incorporated into the calculation. This can be simplified by some developed approximations - such as the Russell-Saunders coupling scheme in L-S coupling, named after H. N. Russell and F. A. Saunders (1925).[3]

See also

- Clebsch–Gordan coefficients

- L-S coupling

- Angular momentum diagrams (quantum mechanics)

- Spherical basis

References

- ↑ Quanta: A handbook of concepts, P.W. Atkins, Oxford University Press, 1974, ISBN:0-19-855493-1

- ↑ Physical chemistry, P.W. Atkins, Oxford University Press, 1978, ISBN:0-19-855148-7

- ↑ Russell, H. N.; Saunders, F. A. (1925). "New Regularities in the Spectra of the Alkaline Earths". The Astrophysical Journal 61: 38–69. doi:10.1086/142872.

- Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei, and Particles (2nd edition), R. Eisberg, R. Resnick, John Wiley & Sons, 1985, ISBN:978-0-471-87373-0

Further reading

- Atomic Many-Body Theory, I. Lindgren, J. Morrison, Springer-Verlag Series in: Chemical Physics No13, 1982, ISBN, Graduate level monograph on many body theory in the context of angular momentum, with much emphasis on graphical representation and methods.

- Quantum Mechanics Demystified, D. McMahon, Mc Graw Hill, 2005, ISBN:0-07-145546-9