Chemistry:Sodalite

| Sodalite | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Category | Tectosilicates without zeolitic H2O |

| Formula (repeating unit) | Na8(Al6Si6O24)Cl2 |

| Strunz classification | 9.FB.10 |

| Crystal system | Cubic |

| Crystal class | Hextetrahedral (43m) H-M symbol: (4 3m) |

| Space group | P43n |

| Unit cell | a = 8.876(6) Å; Z = 1 |

| Identification | |

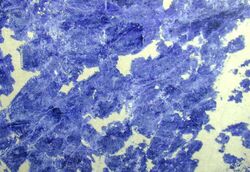

| Color | Rich royal blue, green, yellow, violet, white veining common |

| Crystal habit | Massive; rarely as dodecahedra |

| Twinning | Common on {111} forming pseudohexagonal prisms |

| Cleavage | Poor on {110} |

| Fracture | Conchoidal to uneven |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 5.5–6 |

| |re|er}} | Dull vitreous to greasy |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent to translucent |

| Specific gravity | 2.27–2.33 |

| Optical properties | Isotropic |

| Refractive index | n = 1.483 – 1.487 |

| Ultraviolet fluorescence | Bright red-orange cathodoluminescence and fluorescence under LW and SW UV, with yellowish phosphorescence; may be photochromic in magentas |

| Fusibility | Easily to a colourless glass; sodium yellow flame |

| Solubility | Soluble in hydrochloric acid and nitric acid |

| References | [1][2][3][4] |

| Major varieties | |

| Hackmanite | Tenebrescent; violet-red or green fading to white |

Sodalite (/ˈsoʊ.dəˌlaɪt/ SOH-də-lyte) is a tectosilicate mineral with the formula Na8(Al6Si6O24)Cl2, with royal blue varieties widely used as an ornamental gemstone. Although massive sodalite samples are opaque, crystals are usually transparent to translucent. Sodalite is a member of the sodalite group with hauyne, nosean, lazurite and tugtupite.

The people of the Caral culture traded for sodalite from the Collao altiplano.[6] First discovered by Europeans in 1811 in the Ilimaussaq intrusive complex in Greenland, sodalite did not become widely important as an ornamental stone until 1891 when vast deposits of fine material were discovered in Ontario, Canada.

Structure

Natural sodalite holds primarily chloride anions in the cages, but they can be substituted by other anions such as sulfate, sulfide, hydroxide, trisulfur with other minerals in the sodalite group representing end member compositions. The sodium can be replaced by other alkali group elements, and the chloride by other halides. Many of these have been synthesized.[7]

The characteristic blue color arises mainly from caged S−

3 and S

4 clusters.[8]

Properties

A light, relatively hard yet fragile mineral, sodalite is named after its sodium content; in mineralogy it may be classed as a feldspathoid. Well known for its blue color, sodalite may also be grey, yellow, green, or pink and is often mottled with white veins or patches. The more uniformly blue material is used in jewellery, where it is fashioned into cabochons and beads. Lesser material is more often seen as facing or inlay in various applications.

Although somewhat similar to lazurite and lapis lazuli, sodalite rarely contains pyrite (a common inclusion in lapis) and its blue color is more like traditional royal blue rather than ultramarine. It is further distinguished from similar minerals by its white (rather than blue) streak. Sodalite's six directions of poor cleavage may be seen as incipient cracks running through the stone.

Most sodalite will fluoresce orange under ultraviolet light, and hackmanite exhibits tenebrescence.[9]

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Small specimen of sodalite from Brazil. |

Hackmanite

Hackmanite is a variety of sodalite exhibiting tenebrescence.[10] When hackmanite from Mont Saint-Hilaire (Quebec) or Ilímaussaq (Greenland) is freshly quarried, it is generally pale to deep violet but the color fades quickly to greyish or greenish white. Conversely, hackmanite from Afghanistan and the Myanmar Republic (Burma) starts off creamy white but develops a violet to pink-red color in sunlight. If left in a dark environment for some time, the violet will fade again. Tenebrescence is accelerated by the use of longwave or, particularly, shortwave ultraviolet light. Much sodalite will also fluoresce a patchy orange under UV light.

Occurrence

Sodalite was first described in 1811 for the occurrence in its type locality in the Ilimaussaq complex, Narsaq, West Greenland.[1]

Occurring typically in massive form, sodalite is found as vein fillings in plutonic igneous rocks such as nepheline syenites. It is associated with other minerals typical of silica-undersaturated environments, namely leucite, cancrinite and natrolite. Other associated minerals include nepheline, titanian andradite, aegirine, microcline, sanidine, albite, calcite, fluorite, ankerite and baryte.[3]

Significant deposits of fine material are restricted to but a few locales: Bancroft, Ontario (Princess Sodalite Mine), and Mont-Saint-Hilaire, Quebec, in Canada; and Litchfield, Maine, and Magnet Cove, Arkansas, in the US. The Ice River complex, near Golden, British Columbia, contains sodalite.[11] Smaller deposits are found in South America (Brazil and Bolivia), Portugal, Romania, Burma and Russia. Hackmanite is found principally in Mont-Saint-Hilaire and Greenland.

Euhedral, transparent crystals are found in northern Namibia and in the lavas of Vesuvius, Italy.

Sodalitite is a type of extrusive igneous rock rich in sodalite.[12] Its intrusive equivalent is sodalitolite.[12]

History

The people of the Caral culture traded for sodalite from the Collao altiplano.[13]

Synthesis

The mesoporous cage structure of sodalite makes it useful as a container material for many anions. Some of the anions known to have been included in sodalite-structure materials include nitrate,[14] iodide,[15] iodate,[16] permanganate,[17] perchlorate,[18] and perrhenate.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mindat with locations

- ↑ Webmineral data

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Handbook of Mineralogy

- ↑ Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis, 1985, Manual of Mineralogy, 20th ed., ISBN:0-471-80580-7

- ↑ Warr, Laurence N. (June 2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine 85 (3): 291–320. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. Bibcode: 2021MinM...85..291W.

- ↑ Sanz, Nuria; Arriaza, Bernardo T.; Standen, Vivien G., eds (2015). The Chinchorro culture: a comparative perspective, the archaeology of the earliest human mummification. UNESCO Publishing. p. 162. ISBN 978-92-3-100020-1. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000227775.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHassan - ↑ Chukanov, Nikita V.; Sapozhnikov, Anatoly N.; Shendrik, Roman Yu.; Vigasina, Marina F.; Steudel, Ralf (23 November 2020). "Spectroscopic and Crystal-Chemical Features of Sodalite-Group Minerals from Gem Lazurite Deposits". Minerals 10 (11): 1042. doi:10.3390/min10111042. Bibcode: 2020Mine...10.1042C.

- ↑ Bettonville, Suzanne (25 March 2011). Rock Roles: Facts, Properties, and Lore of Gemstones. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-257-03762-9.[self-published source?]

- ↑ Kondo, D.; Beaton, D. (2009). "Hackmanite/Sodalite from Myanmar and Afghanistan". Gems and Gemology 45 (1): 38–43. doi:10.5741/GEMS.45.1.38. https://www.gia.edu/doc/Sodalite-from-Myanmar-and-Afghanistan.pdf.

- ↑ Ice River deposit on Mindat

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Le Maitre, R.W., ed (2002). Igneous Rocks — A Classification and Glossary of Terms (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 143. ISBN 0-521-66215-X.

- ↑ Sanz, Nuria; Arriaza, Bernardo T.; Standen, Vivien G., eds (2015). The Chinchorro culture: a comparative perspective, the archaeology of the earliest human mummification. UNESCO Publishing. p. 162. ISBN 978-92-3-100020-1. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000227775.

- ↑ Buhl, Josef-Christian; Löns, Jürgen (1996). "Synthesis and crystal structure of nitrate enclathrated sodalite Na8[AlSiO4]6(NO3)2". Journal of Alloys and Compounds 235: 41–47. doi:10.1016/0925-8388(95)02148-5.

- ↑ Nakazawa, T.; Kato, H.; Okada, K.; Ueta, S.; Mihara, M. (2000). "Iodine Immobilization by Sodalite Waste Form". MRS Proceedings 663. doi:10.1557/PROC-663-51.

- ↑ Buhl, Josef-Christian (1996). "The properties of salt-filled sodalites. Part 4. Synthesis and heterogeneous reactions of iodate-enclathrated sodalite Na8[AlSiO4]6(IO3)2−x(OH·H2O)x; 0.7 < x < 1.3". Thermochimica Acta 286 (2): 251–262. doi:10.1016/0040-6031(96)02971-1.

- ↑ Brenchley, Matthew E.; Weller, Mark T. (1994). "Synthesis and structures of M8[ALSiO4]6·(XO4)2, M = Na, Li, K; X = Cl, Mn Sodalites". Zeolites 14 (8): 682–686. doi:10.1016/0144-2449(94)90125-2.

- ↑ Veit, Th.; Buhl, J.-Ch.; Hoffmann, W. (1991). "Hydrothermal synthesis, characterization and structure refinement of chlorate- and perchlorate-sodalite". Catalysis Today 8 (4): 405–413. doi:10.1016/0920-5861(91)87019-J.

External links

|