Astronomy:UY Scuti

DSS2 image of red supergiant star UY Scuti (brightest star in the image), surrounded by a dense starfield. | |

| Observation data Equinox J2000.0]] (ICRS) | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Scutum |

| Right ascension | 18h 27m 36.5334s[1] |

| Declination | −12° 27′ 58.866″[1] |

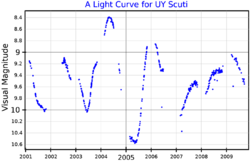

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 8.29 - 10.56[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Evolutionary stage | Red supergiant[3] |

| Spectral type | M2-M4Ia-Iab[2] |

| U−B color index | +3.29[4] |

| B−V color index | +3.00[5] |

| Variable type | SRc[6] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | 18.33±0.82[7] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 1.3[8] mas/yr Dec.: −1.6[8] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 0.5166 ± 0.0494[9] mas |

| Distance | 5,871+534 −446[10] ly (1,800+164 −137[10] pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −6.2[11] |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

Coordinates: ![]() 18h 27m 36.53s, −12° 27′ 58.9″

UY Scuti (BD-12°5055) is a red supergiant star in the constellation Scutum. It is possibly considered one of the largest known stars by radius and is also a pulsating variable star, with a maximum brightness of magnitude 8.29 and a minimum of magnitude 10.56. Its radius has been given various estimates with high uncertainty, including 1,708 ± 192 solar radii (1.188×109 ± 134,000,000 kilometres; 7.94 ± 0.89 astronomical units), thus a volume nearly 5 billion times that of the Sun, as based on the modelling spectrum by the Very Large Telescope (VLT),[4][12][11] and 755 solar radii (525,000,000 kilometres; 3.51 astronomical units), thus a volume over 2 billion times that of the Sun, as based on parallax measurements by the GAIA DR2 database.[13] It is approximately 1.8 kiloparsecs (5,900 light-years) from Earth as measured by the GAIA EDR3 database.[10] Nonetheless, based on these estimates, if placed at the center of the Solar System, its photosphere in general would possibly approach the orbit of Jupiter.

18h 27m 36.53s, −12° 27′ 58.9″

UY Scuti (BD-12°5055) is a red supergiant star in the constellation Scutum. It is possibly considered one of the largest known stars by radius and is also a pulsating variable star, with a maximum brightness of magnitude 8.29 and a minimum of magnitude 10.56. Its radius has been given various estimates with high uncertainty, including 1,708 ± 192 solar radii (1.188×109 ± 134,000,000 kilometres; 7.94 ± 0.89 astronomical units), thus a volume nearly 5 billion times that of the Sun, as based on the modelling spectrum by the Very Large Telescope (VLT),[4][12][11] and 755 solar radii (525,000,000 kilometres; 3.51 astronomical units), thus a volume over 2 billion times that of the Sun, as based on parallax measurements by the GAIA DR2 database.[13] It is approximately 1.8 kiloparsecs (5,900 light-years) from Earth as measured by the GAIA EDR3 database.[10] Nonetheless, based on these estimates, if placed at the center of the Solar System, its photosphere in general would possibly approach the orbit of Jupiter.

Nomenclature and history

UY Scuti was first catalogued in 1860 by German astronomers at the Bonn Observatory, who were completing a survey of stars for the Bonner Durchmusterung Stellar Catalogue.[15] It was designated BD-12°5055, the 5,055th star between 12°S and 13°S counting from 0h right ascension.

On detection in the second survey, the star was found to have changed slightly in brightness, suggesting that it was a new variable star. In accordance with the international standard for designation of variable stars, it was called UY Scuti, denoting it as the 38th variable star of the constellation Scutum.[16]

UY Scuti is located a few degrees north of the A-type star Gamma Scuti and northeast of the Eagle Nebula. Although the star is very luminous, it is, at its brightest, only 9th magnitude as viewed from Earth, due to its distance and location in the Zone of Avoidance within the Cygnus rift.[17]

Characteristics

UY Scuti is a dust-enshrouded bright red supergiant[18] and is classified as a semiregular variable with an approximate pulsation period of 740 days.[6][19][20] Based on an old radius data of 1,708 R☉, this pulsation would be an overtone of the fundamental pulsation period, or it may be a fundamental mode corresponding to a smaller radius.[21]

In the summer of 2012, AMBER interferometry with the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in the Atacama Desert in Chile was used to measure the parameters of three red supergiants near the Galactic Center region:[4] UY Scuti, AH Scorpii, and KW Sagittarii. They determined that all three stars are over 1,000 times bigger than the Sun and over 100,000 times more luminous than the Sun. The stars' sizes were calculated using the Rosseland radius, the location at which the optical depth is 2⁄3,[12] with distances adopted from earlier publications. UY Scuti was analyzed to be the largest and the most luminous of the three stars measured, at 1,708 ± 192 R☉ (1.188×109 ± 134,000,000 km; 7.94 ± 0.89 astronomical unit|AU) based on an angular diameter of 5.48±0.10 mas and an assumed distance of 2.9±0.317 kiloparsecs (kpc) (about 9,500±1,030 light-years) which was originally derived in 1970 based on the modelling of the spectrum of UY Scuti.[11] The luminosity is then calculated to be 340,000 L☉ at an effective temperature of 3,365±134 K, giving an initial mass of 25 M☉ (possibly up to 40 M☉ for a non-rotating star).[4]

The distance of UY Scuti has been re-measured, based on noiseless data from Gaia EDR3, giving a much closer distance 1,800+164

−137 pc away from Earth.[10]

UY Scuti has no known companion star and so its mass is uncertain. However, it is expected on theoretical grounds to be between 7 and 10 M☉.[4] Mass is being lost at 5.8×10−5 M☉ per year, leading to an extensive and complex circumstellar environment of gas and dust.[22]

Supernova

Based on current models of stellar evolution, UY Scuti has begun to fuse helium, and continues to fuse hydrogen in a shell around the core. The location of UY Scuti deep within the Milky Way disc suggests that it is a metal-rich star.[23]

After fusing heavy elements, its core will begin to produce iron, disrupting the balance of gravity and radiation in its core and resulting in a core collapse supernova. It is expected that stars like UY Scuti should evolve back to hotter temperatures to become a yellow hypergiant, luminous blue variable, or a Wolf–Rayet star, creating a strong stellar wind that will eject its outer layers and expose the core, before exploding as a type IIb, IIn, or type Ib/Ic supernova.[24]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hog, E.; Kuzmin, A.; Bastian, U.; Fabricius, C.; Kuimov, K.; Lindegren, L.; Makarov, V. V.; Roeser, S. (1998). "The TYCHO Reference Catalogue". Astronomy and Astrophysics 335: L65. Bibcode: 1998A&A...335L..65H.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "VSX: Detail for UY Sct". American Association of Variable Star Observers. https://www.aavso.org/vsx/index.php?view=detail.top&oid=34154.

- ↑ Tabernero, H. M.; Dorda, R.; Negueruela, I.; Marfil, E. (2021). "The nature of VX Sagitarii". Astronomy & Astrophysics 646: A98. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039236.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Arroyo-Torres, B.; Wittkowski, M.; Marcaide, J. M.; Hauschildt, P. H. (2013). "The atmospheric structure and fundamental parameters of the red supergiants AH Scorpii, UY Scuti, and KW Sagittarii". Astronomy & Astrophysics 554: A76. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201220920. Bibcode: 2013A&A...554A..76A.

- ↑ Ducati, J. R. (2002). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Photometry in Johnson's 11-color system". CDS/ADC Collection of Electronic Catalogues 2237: 0. Bibcode: 2002yCat.2237....0D.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Kholopov, P. N.; Samus, N. N.; Kazarovets, E. V.; Perova, N. B. (1985). "The 67th Name-List of Variable Stars". Information Bulletin on Variable Stars 2681: 1. Bibcode: 1985IBVS.2681....1K.

- ↑ Brown, A. G. A. (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics 616: A1. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051. Bibcode: 2018A&A...616A...1G. Gaia DR2 record for this source at VizieR.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Høg, E.; Fabricius, C.; Makarov, V. V.; Urban, S.; Corbin, T.; Wycoff, G.; Bastian, U.; Schwekendiek, P. et al. (2000). "The Tycho-2 catalogue of the 2.5 million brightest stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics 355: L27. doi:10.1888/0333750888/2862. ISBN 978-0333750889. Bibcode: 2000A&A...355L..27H.

- ↑ Brown, A. G. A. (2021). "Gaia Early Data Release 3: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics 649: A1. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039657. Bibcode: 2021A&A...649A...1G. Gaia EDR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Bailer-Jones, C. A. L.; Rybizki, J.; Fouesneau, M.; Demleitner, M.; Andrae, R. (2021). "Estimating Distances from Parallaxes. V. Geometric and Photogeometric Distances to 1.47 Billion Stars in Gaia Early Data Release 3". The Astronomical Journal 161 (3): 147. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/abd806. Bibcode: 2021AJ....161..147B.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Lee, T. A. (1970). "Photometry of high-luminosity M-type stars". Astrophysical Journal 162: 217. doi:10.1086/150648. Bibcode: 1970ApJ...162..217L.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Wehrse, R.; Scholz, M.; Baschek, B. (June 1991). "The parameters R and Teff in stellar models and observations". Astronomy and Astrophysics 246 (2): 374–382. Bibcode: 1991A&A...246..374B.

- ↑ Messineo, M.; Brown, A. G. A. (2019). "A Catalog of Known Galactic K-M Stars of Class I Candidate Red Supergiants in Gaia DR2". The Astronomical Journal 158 (1): 20. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ab1cbd. Bibcode: 2019AJ....158...20M.

- ↑ "ASAS All Star Catalogue". The All Sky Automated Survey. http://www.astrouw.edu.pl/asas/?page=aasc.

- ↑ Bonner Durchmusterung (Argelander 1859–1862) (clicking on "bd.gz" downloads the gzipped 10.1 MB catalogue)

- ↑ Prager, R. (1927). "Katalog und Ephemeriden veraenderlicher Sterne fuer 1927". Kleine Veroeffentlichungen der Universitaetssternwarte zu Berlin Babelsberg 1: 1.i. Bibcode: 1927KVeBB...1....1P.

- ↑ "UY Sct (UY Scuti)". http://www.kusastro.kyoto-u.ac.jp/vsnet/gcvs2/SCTUY.html.

- ↑ Van Loon, J. Th.; Cioni, M.-R. L.; Zijlstra, A. A.; Loup, C. (2005). "An empirical formula for the mass-loss rates of dust-enshrouded red supergiants and oxygen-rich Asymptotic Giant Branch stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics 438 (1): 273–289. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20042555. Bibcode: 2005A&A...438..273V.

- ↑ Whiting, Wendy A. (1978). "Observations of Three Variable Stars in Scutum". The Journal of the American Association of Variable Star Observers 7 (2): 71. Bibcode: 1978JAVSO...7...71W.

- ↑ Jura, M.; Kleinmann, S. G. (1990). "Mass-losing M supergiants in the solar neighborhood". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 73: 769. doi:10.1086/191488. Bibcode: 1990ApJS...73..769J.

- ↑ Joyce, Meridith; Leung, Shing-Chi; Molnár, László; Ireland, Michael; Kobayashi, Chiaki; Nomoto, Ken'Ichi (2020). "Standing on the Shoulders of Giants: New Mass and Distance Estimates for Betelgeuse through Combined Evolutionary, Asteroseismic, and Hydrodynamic Simulations with MESA". The Astrophysical Journal 902 (1): 63. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/abb8db. Bibcode: 2020ApJ...902...63J.

- ↑ Sylvester, R. J.; Skinner, C. J.; Barlow, M. J. (1998). "Silicate and hydrocarbon emission from Galactic M supergiants". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 301 (4): 1083–1094. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.1998.02078.x. Bibcode: 1998MNRAS.301.1083S. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/10096081/1/sylvester98_msgts.pdf.

- ↑ Meynet, Georges (2008). Israelian, Garik. ed. The metal-rich universe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521879989. http://www.cambridge.org/asia/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521879989. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ↑ Groh, Jose H.; Meynet, Georges; Georgy, Cyril; Ekström, Sylvia (2013). "Fundamental properties of core-collapse supernova and GRB progenitors: Predicting the look of massive stars before death". Astronomy & Astrophysics 558: A131. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321906. Bibcode: 2013A&A...558A.131G.

|